Aircraft Strength and Losses

British Air Force Strength During the Battle of Britain Date No Hurricanes No Spitfires 21 August 1940 615 326 30 August 1940 580 287 8 September 1940 530 275 15 September 1940 472 256 2 October 1940 482 281 18 October 1940 512 285

Book Reference: Number of immediately available fighters, according to "The Battle of Britain" by Peter G. Cooksley (Ian Allan Ltd., 1990)

RAF July losses during the Battle of Britain 1940 R.A.F. Fighter Command Aircraft Destroyed Damaged Pilots KIA Pilots MIA Pilots wounded Hurricane 33 destroyed 17 damaged 23 killed 0 missing 11 wounded Spitfire 34 destroyed 24 damaged 25 killed 0 missing 9 wounded Blenheim 4 destroyed 1 damaged 9 killed 0 missing 1 wounded Defiant 6 destroyed 1 damaged 10 killed 0 missing 2 wounded TOTAL: 77 destroyed 43 damaged 67 killed 0 missing 23 wounded

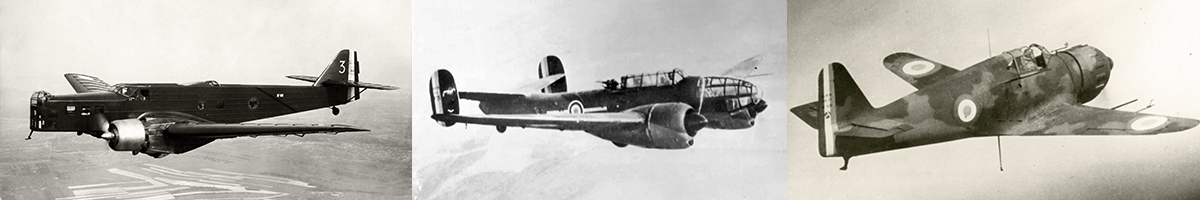

Luftwaffe July losses during the Battle of Britain 1940 Luftwaffe Aircraft Destroyed Damaged Pilots KIA Pilots MIA Pilots wounded Dornier Do 17 39 destroyed 13 damaged 30 killed 74 missing 19 wounded Junkers Ju 87 13 destroyed 11 damaged 10 killed 12 missing 3 wounded Junkers Ju 88 39 destroyed 11 damaged 52 killed 67 missing 11 wounded Heinkel He 111 32 destroyed 3 damaged 52 killed 85 missing 6 wounded Messerschmitt Bf 109 48 destroyed 14 damaged 17 killed 14 missing 13 wounded Messerschmitt Bf 110 18 destroyed 4 damaged 13 killed 17 missing 2 wounded Other 27 destroyed 1 damaged 19 killed 33 missing 15 wounded TOTAL: 216 destroyed 57 damaged 193 killed 302 missing 69 wounded

RAF August losses during the Battle of Britain 1940

RAF August losses during the Battle of Britain 1940 R.A.F. Fighter Command Aircraft Destroyed Damaged Pilots KIA Pilots MIA Pilots wounded Hurricane 211 destroyed 44 damaged 85 killed 1 missing 68 wounded Spitfire 113 destroyed 40 damaged 41 killed 3 missing 38 wounded Blenheim 13 destroyed 10 damaged 6 killed 3 missing 0 wounded Defiant 7 destroyed 3 damaged 7 killed ? missing 4 wounded Beaufighter 0 destroyed 1 damaged 0 killed 0 missing 0 wounded TOTAL: 344 destroyed 98 damaged 139 killed 7 missing 110 wounded

Luftwaffe August losses during the Battle of Britain 1940

Luftwaffe August losses during the Battle of Britain 1940 Luftwaffe Aircraft Destroyed Damaged Pilots KIA Pilots MIA Pilots wounded Dornier Do 17 71 destroyed 30 damaged 70 killed 129 missing 57 wounded Junkers Ju 87 57 destroyed 16 damaged 35 killed 58 missing 19 wounded Junkers Ju 88 89 destroyed 32 damaged 94 killed 182 missing 19 wounded Heinkel He 111 89 destroyed 15 damaged 113 killed 204 missing 35 wounded Messerschmitt Bf 109 217 destroyed 45 damaged 54 killed 91 missing 39 wounded Messerschmitt Bf 110 119 destroyed 40 damaged 80 killed 113 missing 22 wounded Other 27 destroyed 4 damaged 17 killed 27 missing 10 wounded TOTAL: 669 destroyed 182 damaged 463 killed 804 missing 201 wounded

RAF September/October losses during the Battle of Britain 1940

RAF September/October losses during the Battle of Britain 1940 R.A.F. Fighter Command Aircraft Destroyed Damaged Pilots KIA Pilots MIA Pilots wounded Hurricane 294 destroyed 77 damaged 107 killed 2 missing 10 wounded Spitfire 195 destroyed 76 damaged 67 killed 1 missing ? wounded Blenheim 12 destroyed 4 damaged 26 killed 3 missing 55 wounded TOTAL: 501 destroyed 157 damaged 200 killed 6 missing 162 wounded

Luftwaffe September/October losses during the Battle of Britain 1940

Luftwaffe September/October losses during the Battle of Britain 1940 Luftwaffe Aircraft Destroyed Damaged Pilots KIA Pilots MIA Pilots wounded Dornier Do 17 82 destroyed 36 damaged 147 killed 94 missing 50 wounded Junkers Ju 87 1 destroyed 3 damaged 1 killed, ? missing ? wounded Junkers Ju 88 175 destroyed 85 damaged 251 killed 227 missing 74 wounded Heinkel He 111 131 destroyed 78 damaged 203 killed 184 missing 67 wounded Messerschmitt Bf 109 326 destroyed 96 damaged 77 killed 159 missing 36 wounded Messerschmitt Bf 110 124 destroyed 26 damaged 91 killed 109 missing 17 wounded Other 43 destroyed 7 damaged 23 killed 35 missing 16 wounded TOTAL: 882 destroyed 331 damaged 793 killed 808 missing 260 wounded

Spitfire vs. Hurricane during the Battle of Britain

Book Reference: From 'Spitfire Special' by Ted Hooton

Spitfire vs. Hurricane during the Battle of Britain Spitfire vs. Hurricane during the Battle of Britain Spitfire Hurricane Time Period Average Strength 295 461 11th Group 137 243 Average Strength 38% 62% July 1- September 30 German shot down 43% 57% July 1 - September 30 Bf 109 shot down 49% (of all lost) July - August Bf 109 shot down 54% (of all lost) September Combat losses 39% 61% Accident rate 7% 7%

Spitfire vs. Bf 109: 219 to 180 lost respectively.

Hurricane vs. Bf 109: 272 to 153 lost respectively.

Battle of Britain Jul-Aug 1940

In order to establish the necessary conditions for the final conquest of England I intend to intensify air and sea warfare against the English homeland. I therefore order as follows:

The German Air Force is to overpower the English Air Force with all the forces at its command, in the shortest time possible. The attacks are to be directed primarily against flying units, their ground installations and their supply organizations, but also against the aircraft industry, including that manufacturing anti-aircraft equipment.

After achieving temporary or local air superiority the air war is to be continued against ports, in particular against stores of food, and also against stores of provisions in the interior of the country. Attacks on the south coast ports will be made on the smallest scale, in view of our own forthcoming operations.

On the other hand, air attacks on enemy warships and merchant ships may be reduced except where some particularly favorable target happens to present itself; where such attacks would lend additional effectiveness to those mentioned in paragraph 2, or where such attacks are necessary for the training of aircrews for further operations.

The intensified air warfare will be carried out in such a way that the Air Force can at any time be called upon to give adequate support to naval operations against suitable targets. It must also be ready to take part in full force in Operation Sealion.

I reserve to myself the right to decide on terror attacks as measures of reprisal.

The intensification of the air war may begin on or after 5 August. The exact time is to be decided by the Air Force after the completion of preparations and in the light of the weather.

The Navy is authorized to begin the proposed intensified naval war at the same time.

Adolf Hitler

Directive No. 17 for the conduct of Air and Sea Warfare against England August 01, 1940

The British have lost the war !!!

"The British have lost the war, but they don't know it; one must give them time and they will come round."

Adolf Hitler commenting to General Alfred Jodi following the Franco-German Armistice in June 1940

June 1940 and Germany was riding the crest of a wave. Virtually everything in the campaigns against France and the Low Countries had gone according to plan. In a period of less than two months much of Western Europe had been brought under German occupation and control. All that now stood between Germany and complete domination of the whole area was Great Britain. A victorious Adolf Hitler, although preoccupied with his thoughts on the conquest of Russia, now looked for a rapid and favorable decision in the war against Britain and retained the hope that a negotiated settlement with her could be reached. However, as it became increasingly clear that no such agreement would be forthcoming, his attention began to focus on the forceful subjugation of the island kingdom, including if necessary, its invasion and occupation.

With no indication that a peaceful settlement of any kind would be reached, the OKW was now given the task of preparing for and, if necessary, achieving the successful invasion of Great Britain. For an invasion to succeed, it would have to take place within a three-month period of anticipated good weather under complete air superiority, and before the onset of the autumnal channel gales.

"The near future will show whether Britain will do the reasonable thing in the light of our victories or will try to carryon the war alone. In the latter case the war will involve Britain's destruction and may last a long time."

General Franz Halder, diary entry 22 June 1940.

With their record of military successes, it is not surprising that both Hitler and the OKW General Staff retained a purely continental view of carrying out such an invasion; an operation which they likened to a powerful river crossing on a broad front with the Luftwaffe taking the place of artillery. It was believed that the well-proven Blitzkrieg tactic, i.e. destruction of the opposing air force, followed by the rapid advance of the German Army with its powerful and direct air-support would also succeed against Great Britain. There was, however, one major difference - the Royal Air Force; it was the single most powerful air force yet encountered by the Luftwaffe. Bearing this and their recent successes against other European air forces in mind, the Oberkommando der Luftwaffe estimated that its complete destruction would take longer than the 12 to 48 hours taken to defeat each of the air forces fought previously. Furthermore, it was known that the British would put up a fierce and determined fight in defence of their homeland. Based on these calculations, the OKL predicted that, in the event that an invasion should take place, a period of four days would be needed to secure total air superiority in the immediate invasion area. It further anticipated that in the wake of a successful invasion, the complete destruction of the Royal Air Force could be achieved within a period of no more than three weeks. The key to the successful completion of any invasion, however, would be German supremacy in the air.

"The landing in England, prepared down to the smallest detail, could not be attempted before the British air arm was completely beaten".

General Alfred Jodi, Munchen, November 1945

Studie Blau' (Case Blue)

In 1940 the Luftwaffe was undoubtedly the most powerful air force in the world but the German intelligence system was disorganised and inefficient. It was against this background that on, 1 January 1938 Abteilung 5, the intelligence section of the Luftwaffe General Staff was formed, tasked with the collection of information on foreign air forces and the preparation of target information for use in any future air war. Command of Abteilung 5 as Chief IC (Intelligence) was given to Major Joseph Schmid who, although a shrewd and ambitious man, had no foreign language skills and was not a pilot. It is perhaps significant of the value placed on intelligence by the Luftwaffe that the appointment required only the rank of Major. For the last few months of 1938 and the first half of 1939, Schmid and members of Abteilung 5 carried out studies on Poland, Russia and England. While the preliminary work on England was being undertaken, an order was received from the Commander in Chief of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Goring, demanding a high priority study of the air and industrial armaments capability of Great Britain. This subject was considered so important that a study committee was formed with Erhard Milch, Ernst Udet and Hans Jeschonnek as permanent members and Schmid as chairman. The result of this study was a full report on Britain that appeared in July 1939 under the title of 'Studie Blau' (Case Blue). For most of the Second World War, this document would provide the basic reference material on which attacks against England were planned.

While realizing that, militarily, England was an enemy to be respected, Schmid had already begun to under-estimate the efficiency and potential of the RAF. During the latter part of 1939, he devoted most of his time to formulating an offensive plan against England which would severely damage her, regardless of the outcome of the campaign against France. In late November 1939, this document was issued under the title 'Proposal for the Conduct of Air Warfare against Great Britain'. Although far-sighted, it was probably the last study in which Schmid was able to make an objective and accurate forecast concerning Britain. While the theme of this study concentrated on the strangulation of Britain's ocean supply lines and harbor facilities he neglected to take into account two very important factors; the potential danger of the British radar chain and the lack of German maritime and torpedo bombers.

As the time passed, Schmid concentrated on 'Studie Blau' and the mass of information captured by Germany with the fall of France. On 16 July 1940, having compiled and studied all of the available background information, Schmid completed an overall survey on the qualities of the RAF and on which the coming offensive would be based. Aside from containing numerous misleading and inaccurate statements regarding the military and operational capabilities of the RAF, the study omitted any reference whatsoever to the closely-knit British defence system with its radar stations, operations rooms and complex HF and VHF radio network. In conclusion, Schmid stated that "The Luftwaffe is in a position to go over to decisive daylight operations owing to the inadequate air defences of the island."

Enigma Ultra decrypts and the Battle of Britain

In addition to an established defensive warning system, Britain had one other measure that she could employ in her defence - decoded transcripts of German signals traffic sent by the Enigma coding system. First coming into use during the summer of 1940, the 'Ultra decrypts' as they became known, were useful to the planning of RAF strategy but did not offer the scope of material that would become available as the war progressed. As the Luftflotten proceeded to follow Goring's orders, they found defending RAF fighters were nearly always there to meet them, in the right place, and, whenever possible, in significant numbers. Directed not only by the chain of RDF stations and radio communications, they were also guided by information obtained from the contents of decoded signals intercepted from the flow of Enigma traffic between the OKL and Luftwaffe units. This access to German planning strategy allowed the head of RAF Fighter Command, Air Chief Marshal Dowding and his Group Commanders, to apportion their resources accordingly and stem the Luftwaffe onslaught.

Although the decrypts of the Luftwaffe's intentions clearly had an impact on the final outcome of the Battle, exactly how far they contributed to the ultimate victory of the RAF during 1940 remains an ongoing topic of discussion amongst historians to this day.

Preparation: July 1940

Until the end of the campaign in the West, the air war against Great Britain had been carried out on a limited scale, being confined for the most part to mine-laying, attacks against merchant and naval shipping and attacks on targets of a secondary nature. Then in June 1940, with the countries of Western Europe under German occupation, the circumstances changed. The airfields and installations of occupied Europe provided every facility to allow the full strength of the Luftwaffe to be strategically deployed against Britain. However, despite being in such an advantageous position, the Luftwaffe was faced with a formidable task, one that begged the question; "If Britain fought on, could air power alone defeat her?

In supporting the Army in its march across Europe, the Luftwaffe had played an important and decisive role in the tactic of Blitzkrieg. There it had been used to open each offensive by destroying the opposing air force in the air or on the ground before joining with the rapid advance of the Army to give powerful and direct air-support wherever needed. But in the mid-summer of 1940, for the first time in its history, the Luftwaffe would embark on a course of action that had no precedent in the history of modern warfare. Wholly independent of operations by the remainder of the Wehrmacht, it was to carry out an aerial offensive aimed at decisively defeating an opposing air force and forcing the capitulation of an entire nation.

At this period, total air war was known only as a theoretical conception. Until then no attempts had ever been made to wage war solely by use of air power, independently of the Army or Navy, in order to break the fighting spirit of an enemy equipped with modern arms.

The following were the strategic missions imposed on the Luftwaffe:

a) the blockade of Britain (in conjunction with the Navy) by air attacks on shipping and ports;

b) softening-up for the invasion; offensive aimed at gaining air superiority;

c) forcing Britain to surrender by waging total air war against her.Comment by General Adolf Galland on the role of the Luftwaffe in 1940 in a post-war appraisal of the Battle of Britain, Air Historical Branch Translation VII/121, 1953, p.11

The necessary regrouping of Luftwaffe forces in preparation for the assault on England showed little change from those used in the Battle for France. Luftflotten 2 and 3 had simply extended their areas westwards into France with a common boundary at the mouth of the River Seine on the Channel coast. This boundary was then extended northwards through the centre of England to give each Luftflotte its own sphere of operations. Luftflotte 2 under the command of the competent and newly promoted Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring, would operate to the east of this boundary while Luftflotte 3, under Generalfeldmarschall Hugo Sperrle, similarly recently promoted, would operate to the west. The subordinated Fliegerkorps of each Luftflotte remained unchanged but for one exception; Fliegerkorps /I and IV were interchanged so that Fliegerkorps IV, based in western France with units specialising in the anti-shipping role, would be better placed to operate over the shipping lanes of the Irish Sea and Western Approaches. The Norwegian based Luftflotte 5, under Generaloberst Hans-Jurgen Stumpff, would not play any major role in the early stages of the attack against Britain. However, its bombers and twin-engined fighters would provide valuable widespread anti-shipping and diversionary attacks against Northern England and Scotland which would force the RAF to keep fighter defences in the north, so weakening the aerial defences in the south.

A second change introduced with this regrouping assembled the single and twin-engined fighter units from the Fliegerkorps of each Luftflotten into two tactical fighter commands. Known as 'Jagdfuhrer' or 'Jafus' with Jafu 2 under Luftflotte 2 and Jafu 3 under Luftflotte 3, these commands were able to retain a measure of independence in the planning of escort duties and fighter sweeps within the operational setting of their respective Luftflotte. While similar in purpose to the Fighter Groups of the RAF that they were to face in the coming battles, they lacked any means or procedure for plotting the position of enemy aircraft, nor had they any method for controlling their own fighters once airborne. Therefore, although performing the function of an operational command; aerial operations were flown without any guidance or additional direction from their ground facilities. This disadvantage would undermine the whole effort of the Luftwaffe Fighter Arm.

The Luftwaffe Plan of Campaign July 1940

Within the overall framework of the OKW's plans for the invasion of Great Britain, the two major tasks assigned to the Luftwaffe appeared straight-forward enough: neutralisation of the RAF as a fighting force and the suppression of sea-borne supplies to Britain by attacks on its ports and shipping. Luftflotten 2 and 3 were to achieve and maintain air superiority over southern and south-eastern England while Luftflotte 5 carried out diversionary attacks against Scotland and northern England to prevent some of the defending fighter squadrons from reinforcing those in the south.

Orders issued by the OKL operations staff to the three Luftflotten made it clear how these objectives would be met. In the first phase which would continue until the end of the first week in August, the Luftwaffe would attack British defences and carry out attacks against merchant and naval shipping, port facilities and selected industrial targets. This would be followed by an intensified second phase; a six week major aerial offensive designed to destroy the infrastructure and defensive capabilities of the RAF, neutralise the British coastal defences, wear down initial resistance, destroy military reserves behind the main defences and protect the build-up of invasion forces. This second phase would begin on a day given the code name Adler Tag - 'Eagle Day', the date of which would be determined by the first period of fine weather following the end of the initial phase. The prime objective, however, would be the neutralisation of the RAF and its ground organisation by attacking its aircraft, especially fighters, on the ground and in the air, and attacks against bases and supply installations and against its supporting industry. Once this second phase had been completed in southern England, the offensive, in keeping with the intended OKW plan, would then be extended northwards in a series of stages.

During the third week of July, the Luftwaffe was ordered to a state of full readiness and the final details and operational orders were worked out. The unit strength returns from the three Luftflotten for this week gave them a total of 2,076 serviceable aircraft of which 656 were single-engined fighters and 168 twin-engined fighters. Ranged against them was a total of 1,519 serviceable RAF aircraft of which 606 were single-engined fighters and 101 twin-engined fighters. The stage was now set for a battle that had no precedent in the history of warfare; the greatest and probably most decisive aerial battle ever fought.

1.20 July 1940

In the broadest sense - and with some justification - it may be said that the Battle of Britain began on 30 June 1940. On that day, German forces had landed unopposed on the island of Guernsey, the largest of the four Channel Islands. Within the next 24 hours, this small group of islands, all sovereign territory of Great Britain, would be under full German control. By the end of July, an operational Luftwaffe landing ground had been established at the airfield on Guernsey and would be the only airfield on British soil to be used by the Luftwaffe during the Second World War. It would be from here that elements of JG27 and a Staffel of Major Freiherrvon Maltzahn's II/JG53 would operate against Britain's defenders during the coming battle.

Throughout the first 20 days of July, daylight aerial activity over Britain was generally confined to bombing attacks on coastal shipping, port facilities and industrial targets, while 'freie Jagd' operations were flown by the fighters of JafD 2 and 3. No fighters were lost in combat until the 4th, when two Bf-109s, from III/JG27 and 4.(J)/LG 2, were claimed by P /0 Smythe of 32Sqn during a mission over the English coast. Of the two claimed, that from JG27, although damaged, succeeded in returning to Thewille, but the machine from LG 2 was seen to crash into the sea, the pilot being listed as missing. On the 5th, an aircraft from 2/JG51 was slightly damaged in combat with Spitfires of 64Sqn. No combat losses occurred on the 6th but during the evening of the 7th a 'Freiejagd' by JG27 resulted in the downing of three Spitfires of 64Sqn. Although two victories were claimed by RAF pilots, the only Bf-109E listed as damaged that day, was an aircraft of III/JG27 which was severely damaged in a take-off accident at Theville.

On the 8th, increased activity over Channel convoys resulted in the loss of three fighters including the first Bf-109 E to come down on British soil. At 15.45 hrs this aircraft, 'White 4', an E-3 of 4/JG51 flown by Lt. Johann B6hm, force landed at Bladbean Hill, Elham, Kent after being damaged by a Spitfire of 74Sqn. This was followed at 19.30 hrs by the second Bf-109 to crash in Britain, this time an aircraft from 3.(J)/LG2, which was shot down by 54Sqn and crashed near Sandwich, Kent. The pilot, Lt. Albert Striberny, was captured after baling out. An aircraft from III/JG51 was also lost in action on this date with a fourth from II/JG51 being damaged in combat with 610Sqn. The 9th again saw increased fighter activity over the Thames Estuary and Channel but, despite RAF claims for two Bf-109s shot down, only one, from II/JG51, was recorded as being lost.

"...he saw me almost immediately and rolled out of his turn towards me so that a head-on attack became inevitable. Using both hands on the control column to steady the aircraft and thus keep my aim steady, I peered through the reflector sight at the rapidly closing enemy aircraft. We opened fire together, and immediately a hail of lead thudded into my Spitfire. One moment the Messerschmitt was a clearly defined shape, its wingspan nicely enclosed within the circle of my reflector sight, and the next it was on top of me, a terrifying blur which blotted out the sky ahead. Then we hit."

F/O. A.I. Deere, 54Sqn, commenting on his head-on collision with a Bf-109 of II/JG51 during a dogfight with the fighter escort for a He-59 of Seenotflugkommando 1 during the evening of 9 July 1940.

On 10 July, the major fighter activity of the day took place over the west-bound convoy' Bread' in the English Channel. There were no German fighter losses during the morning's fighting but a JG51 aircraft was claimed as slightly damaged by a Spitfire from 74Sqn. In the afternoon battles above the convoy, one Bf-109 from 5/JG51 was lost while a further two from 7/JG51 were damaged severely enough to result in forced landings in France, both pilots escaping serious injury.

"The whole cockpit stank of burnt insulation but I managed to stretch my glide to the coast, then made a belly-landing close to Cherbourg. As I jumped out the machine was on fire, and within seconds ammunition and fuel went up with a bang!"

Ofw. Arthur Dau, 7/JG51, commenting on what happened after being hit by fire from a Hurricane flown by sgt. A.G. Page, 56Sqn during combat over the convoy 'Bread' 10 July 1940

"Suddenly the sky was full of British fighters. Today we were going to be in for a tough time."

Hptm. Hannes Traut/oft, III/JG51, commenting on the action over the British convoy 'Bread' 10 July 1940

On the 11th, 12th and 13th, attacks on Channel convoys continued resulting in one Bf-109 of 9/JG51 being shot down near Dover on the evening of the 13th. On the 14th, battles again developed over Channel convoys resulting in the loss of one aircraft from 8/JG3 and a second from the same Staffel returning to France severely damaged. Although skirmishes continued for the next four days, operations were hampered by bad weather and no further fighters were lost in combat until the 18th when a Bf-109 of II/JG2 was lost to unspecified reasons during an operational sortie. On the 19th, the day on which Hitler would make his' Last Appeal to Reason' speech, improving weather resulted in increased fighter activity off Dover. In the early afternoon, the Defiants of 141Sqn were badly mauled by fighters of III/JG51 and II/JG2 for the cost of one aircraft of 9/JG51 severely damaged.

In later actions over Folkestone and Selsey Bill, three more fighters from 9/JG51 and III/JG27 were badly damaged with two of the pilots being wounded. Improving weather over the Channel on the 20th saw an early afternoon attack on Dover which claimed two aircraft from 3/JG27. The Geschwader suffered a third loss during the late afternoon when the Gruppe Kommandeur, Major Riegel, was shot down off the island of Sark by two Hurricanes of 501Sqn. Later, in an early evening battle that developed over the convoy ‘Bosom’ two more aircraft, both from JG51, were lost to RAF fighters.

21.31 July 1940

In contrast with the previous day's activity, the 21st was relatively quiet until mid-afternoon when the west-bound convoy 'Peewit' came under heavy attack from elements of KG 3 south of the Needles.

During the ensuing battle between the fighter escort and the defending fighters, one Bf-109 from 7/JG27 was lost when it collided with a 43Sqn Hurricane flown by P/0 De Mancha. Both pilots were killed in the collision. A second loss also occurred this day when a Bf-109 from III/JG77 was lost for unspecified reasons while on an operational sortie over the North Sea. There was little fighter activity over the Channel on the 22nd and 23rd but on the 24th, Channel convoys were again the focus of Luftwaffe attention. An intense fighter battle developed over a convoy in the Straits of Dover which cost JG26 three aircraft; Oblt. Werner Bartels, the Geschwader Technische Offizier (TO) force-landed near Margate and was taken prisoner, Lt. Josef Schauff was killed when his aircraft crashed in Margate and his parachute failed to open and Hptm. Erich Noack, Kommandeur of the second Gruppe, was killed when his Bf-109 crashed while attempting to land at Marquise-East.

Four aircraft from JG52 were also lost in this action, one of these being Hptm. Wolf-Heinrich von Houwald the Kommandeurof III/JG52. On the 25th, another ferocious battle took place over a convoy passing through the Dover Straits that would last through most of the afternoon. This action saw the loss of seven fighters; one from 9/JG26, one from III/JG27 and four from III/JG52. The seventh loss recorded for the day was a severely damaged E-1 from 5/JG51 which was written off after returning to St. Inglevert.

Deteriorating weather over the Channel on the 26th and 27th limited attacks in any strength against convoys and other shipping. On the 27th attacks were carried out against both Dover and the convoy 'Bacon' but the only fighter lost in combat during these two days was an aircraft from 2/JG27, shot down south of Portland by a Hurricane of 238Sqn at noon on the 26th.

"We were no longer in doubt that the RAF would prove a formidable opponent"

Adolf Galland, III/JG26, commenting on his first combat over the English Channel, 24 July 1940

Despite better weather over the Channel on Sunday 28th, no concentrated attacks on shipping developed until early afternoon when an incoming raid was detected heading for Dover. In the battle that followed one machine from 2/JG51 was lost and two others badly damaged, of which one was flown by the Geschwaderkommodore, Major Werner Molders. Also involved in the fighting this day was the highly respected and popular South African from 74Sqn, F/Lt. A.G. 'Sailor' Malan. While some sources have credited Malan with damaging the Bf-109 flown by Molders, others credit the action to Fl./Lt. J. T. Webster of 41Sqn. Although a detailed study of combat reports for this engagement suggest that Malan may have been responsible, it is far more conceivable that the damage was actually inflicted by Webster.

"North of Dover we met some low-flying Spitfires. I shot down a Spitfire in flames. But now I found myself in the middle of a clump of Englishmen and they were very angry with me. They all rushed at me and that was my good luck. As they all tried to earn cheap laurels at the expense of one German, they got in each other's way. Well, I managed to maneuver among them and made them even more confused. Nevertheless, I couldn't avoid being hit. Bullets bespattered my aircraft. The radiator and fuel tank were shot up badly and I had to make a getaway as quickly as possible. Luckily my engine held out to the French coast, then it began to misfire. When I wanted to land, the undercarriage wouldn't work. There was nothing to do but land without it. I made a smooth belly landing."

Major Werner Molders, Stab/JG51, commenting on his first combat over the Channel, 28 July 1940

With more fine weather early on the morning of the 29th, Dover harbor and two Channel convoys were targeted by the Luftwaffe. A heavy raid in the early morning was directed at Dover but was driven off by the anti-aircraft and fighter defences and afternoon attacks carried out against the two convoys caused little damage. Activity over the Channel on this day resulted in four fighters being severely damaged in combat. Of these four, one from I/JG51 crashed at Wissant and one from 6/JG51 crashed outside Calais with both pilots being killed. The two other aircraft from II/JG27 and 4/JG51 force-landed without injury to either pilot. With low cloud and light rain covering most of Britain on the 30th, air activity was greatly reduced and no Bf-109s were lost. Although the weather began to improve on the 31st, hazy conditions frustrated operations. Later that afternoon two Staffeln of Bf-109s from JG2 shooting up barrage balloons in the Dover area were intercepted by Spitfires of 74Sqn. None were shot down but one Bf-109 was damaged and force-landed at Fecamp with a seized engine.

1-12 August 1940

With a day of low cloud and mist heralding the beginning of a new month, the Luftwaffe paid little attention to the convoys around Britain and it was not until the mid-afternoon of 1 August that the convoys 'Agent' and 'Arena' provoked any reaction. During the day no fighters were lost in action but three aircraft of II/JG27 were damaged to varying degrees in an RAF Bomber Command attack on Leeuwarden airfield in northern Holland. Continuing poor weather on the 2nd, 3rd and 4th again limited Luftwaffe offensive operations and there were no fighter combat losses. Fine weather early on the morning of the 5th saw a furious engagement develop over the Kent coast between Spitfires of 64Sqn and aircraft from JG54, which resulted in two Bf-109s returning to France damaged. Later in the day, a battle above a convoy in the Straits of Dover saw one aircraft of JG51 shot down and another returning to its base damaged. On the 6th and 7th aerial activity was again limited as far as fighter actions were concerned. The only operational fighter casualty during these two days was an aircraft from JG3 which was damaged when it force-landed after an operational sortie on the 6th.

"Why marry now when there is only England left? Marry later to celebrate the victory".

Major Werner Molders. Stab/JG51, replying to a request from one of his pilots seeking leave to marry. 7 August 1940

On the morning of the 8th and marking the start of a distinct new phase of attacks, the west-bound convoy' Peewit' was subjected to a series of attacks more intensive than any made against convoys during the preceding month. During the course of the day, three furious air battles took place over and around the convoy. At the end of the day's fighting, nine fighters had been lost with a further eight damaged to varying degrees. Of the units taking part, II/JG27 suffered the most casualties with four aircraft lost and two damaged, one of these losses being the Gruppenkommandeur, Hptm. Werner Andres who survived ditching his aircraft and was later rescued from the Channel by the Seenotdienst.

"The enemy fighters, which were painted silver, were half-rolling and diving and zooming in climbing turns. I fired two five-second bursts at one and saw it dive into the sea. Then I followed another up a zoom and got him as he stalled"

S/Ldr. John Peel, 145Sqn commenting on the battle above the convoy 'Peewit' 8 August 1940.

Activity over the Channel on the 9th and 10th was slight and no fighters were lost on operations, although a Bf-109 of I/JG53 was written-off on the 9th when it hit a Flak emplacement while making an emergency landing on Guernsey due to engine failure at the end of an operational sortie. Improved weather on the 11th again saw the Jagdwaffe out in strength undertaking' Freiejagd' over the Kent and Sussex coasts and escorting attacks carried out on Portland, Weymouth and Channel convoys. Intensive fighting developed during the early morning and continued throughout the day until deteriorating weather in the afternoon brought most aerial activity to an end. The aircraft lost in the actions of the 11th almost doubled those of the 8th, totaling 14 fighters lost and two damaged. The losses to JG2 alone almost equaled those incurred on the 8th and included the Gruppe Adjutant of III/JG2, Oblt. Adolf Steidle and the Staffelkapitan of 6/JG2 Oblt. Edgar Rempel.

With Adler Tag set for the following day, the morning of the 12th dawned bright and clear. This day would witness the first attacks to be carried out against RAF airfields and coastal RDF stations. Set in a series of stages, the attacks moved back and forth along the south coast throughout the day. The airfields of Hawkinge, Lympne and Manston came under heavy attacks and Ventnor RDF station, hit heavily at around midday, was put out of action. Pressure was also maintained in the attacks against coastal shipping and harbors with the convoys 'Arena', 'Agent', 'Snail' and 'Cable' receiving particular attention. Despite the ferocity of the day's fighting, fighter losses were lower than those for the 11th.

In all a total of nine Bf-109s failed to return from the day's actions including that flown by the Gruppenkommandeur of III/JG53, Hptm. Harro Harder. A further five aircraft received various levels of combat damage, one of which, from I/JG2, was subsequently written off.

The attacks carried out against the airfields and RDF stations during the 12th were severe and gave a foretaste of what lay ahead. Although the airfields of Hawkinge, Lympne and Manston were serviceable the next day, it was a full three days before, Ventnor RDF would function again, leaving a vital breach in the British warning system. Fortunately this loss was disguised from German signals intelligence by having the Ventnor signals transmitted by another station until repairs were completed at the site.

Battle of Britain Aug-Sept 1940

From Reichsmarschall Goring to all units of Luftflotten 2, 3 and 5. Operation Adler.

Within a short period you will wipe the British Air Force from the sky.

Heil Hitler.

Reichsmarschall Hermann Goring quoted from an Enigma message sent to Luftwaffe units, 8 August 1940

Until further orders, operations are to be directed exclusively against the enemy Air Force, including the targets of the enemy aircraft industry allocated to the different Luftflotten. Shipping targets, and particularly large naval vessels, are only to be attacked where circumstances are especially favorable.

For the moment, other targets should be ignored.

We must concentrate our efforts on the destruction of the enemy Air Forces. Our night attacks are essentially dislocation raids, made so that the enemy defenses and population shall be allowed no respite. Even these, however, should where possible be directed against Air Force targets.

Reichsmarschall Hermann Goring, Karinhall Conference, 15 August 1940: Paragraph 6 of an address to Luftflotte Senior Staff Reichsmarschall Hermann Goring, Karinhall Conference, August 15, 1940: Paragraph 9 of an address to Luftflotte Senior Staff.

Prelude to Adlertag

Up to 9 August, the Luftwaffe's Operations Staff had foreseen that Adlerangriff would be launched on 10

August, but a forecast of unsettled weather resulted in a postponement until the 13th. Meanwhile, as a result of the heavy losses suffered on 11 August, the Luftwaffe was beginning to appreciate that the British RDF stations were providing Fighter Command with advance warning of approaching raids. It was decided, therefore, that on the 12th all such known stations should be put out of action before Adlertag. The task was entrusted to Hptm. Walter Rubensdorffer's Erprobungsgruppe 210, a specialist unit within Luftflotte 2 then operationally evaluating Bf109 and Bf110 aircraft in the fighter-bomber role. In the course of this evaluation, Erp.Gr210 had since 13 July been operating against shipping, proving so effective that by 30 July, after little more than two weeks active service, Generalfeldmarschall Kesselring congratulated the unit for having sunk 89,000 tons of merchant vessels plus four warships.

The Gruppe establishment comprised a Gruppen Stab and three Staffeln. The Stab, 1. and 2.Staffeln were equipped with the Bf110, most fitted with bomb racks under their fuselages, while the 3.Staffel, commanded by Oblt. Otto Hintze, who had earlier fought in the Polish and French campaigns, was equipped with the Bf109. Although the Bf109s of 3.Staffel were to fly with the Bf110s as escort, each aircraft was fitted with a centreline rack suitable for mounting a single 500KGbomb. At any sign of danger, however, the Bf109s could jettison their bombs and revert to the ordinary fighter role.

Messerschmitt Bf 109E1 5./JG52 Red 14 Leo Zaunbracher WNr 3367 shot down Lewes 12th Aug 1940 IWM

On 12 August, as a prelude to Adlertag, the unit switched its attention to RAF bases and radar stations. The first operations of the day were co-ordinated attacks against Dunkirk (Canterbury), Pevensey, Dover and Rye. The attack on Dover radar station was carried out by the Bf 109s of 3.Staffel which claimed three 500kg bomb hits in the target area, but only slightly damaged the station which continued to operate with emergency equipment. Further sorties were flown the same day when, together with Do 17s from KG3, the unit attacked Manston aerodrome. Despite heavy AA fire, the attackers succeeded in putting the aerodrome out of action until the following day, but as Erp.Gr210 withdrew, it was attacked by the Spitfires of 54Sqn and the Hurricanes of 501Sqn. One of the pilots from 1.Staffel on this mission - making his fifth war flight - was Lt. Erich Beudel, flying one of the unit's Bf 110C-6 aircraft which, instead of carrying a bomb rack, was armed with a 30 mm MK101 cannon. In his diary, he later recorded: "Without any warning, numerous Spitfires and Hurricanes are on top of us. For the most part we beat them off, then a Spitfire sits over me, ready to dive, but I was already in the saving clouds. I skipped from cloud to cloud across the Channel. Suddenly there are a few Hurricanes under the Bf 110s. From the left, one Hurricane gets underneath and behind me. My W/T Operator shouts, "Fighters!" and begins to loose off a drum. I close the radiator shutters tight and squeeze the last ounce out of the engines to catch up with a Kette which is only 100 meters in front of me.

The oil temperature goes over 110 degrees. Suddenly my W/T Operator calls out, 'Tommy's down!" He had been followed by Leutnant Marx who got underneath him and gave him a burst. In the next second he was snaffled by the 109 and fell blazing into the sea. Far below, a parachute opened. At last the coast is reached. The starboard engine's coolant and oil temperatures have risen to 120 degrees. Streams of blue smoke come from the engine, which must seize at any moment. Smoke fills the cockpit. I make an oblique landing and as I touch down the engine stops suddenly. All the coolant had run out owing to a single shot in the radiator; three glancing shots in the propeller and starboard wing".

Because of his damaged aircraft, Lt. Beudel was unable to take part in the Gruppe's third attack of the day, an evening attack on Hawkinge aerodrome. Considerable damage was caused in this attack, and all aircraft returned safely.

A Major Flaw

Although German intelligence had accurately predicted the RAF order of battle, a major flaw in the planned Adlerangriff was the blind faith placed in Oberst Josef Schmid's fundamentally inaccurate 'Studie Blau'. Such was the reliance placed in this document that its accuracy was hardly questioned, even when subsequent information should have allowed it to be updated with more accurate information. One of the results of Schmid's erroneous study was that even as late as 13 August, when Adlerangriff was launched, neither OKW nor ObdL were fully conversant with the operational structure of Fighter Command, its airfield network, or the way in which the British RDF chain controlled the fighter defences. If the Luftwaffe was to eliminate Fighter Command then these matters needed to be clearly understood and targeted accordingly. In the event, the misconceptions which resulted from Schmid's study led, for example, to the naval airfields of Gosport, Detling and Lee-on-Solent being erroneously targeted as front line fighter stations, while Supermarine's Spitfire factory at Woolston was identified as a bomber factory belonging to A.V. Roe & Company.

The result of these intelligence failures was that a major part of the Luftwaffe's effort throughout July and the first twelve days of August was wasted on targets which, even if they had been successfully destroyed, were not important to the operational capability of Fighter Command.

13 August 1940 Adlertag

On the morning of the 13th, Luftflotten 2 and 3 stood ready to open the air offensive. Yet with the assault poised to begin, the temperamental Channel weather again caused another last minute delay. Unsuitable conditions over England and France in the early morning caused Goring to issue an order postponing the start of Adlerangriff until the middle of the afternoon. However, Goring's order failed to reach all units with the result that while most stood down, others continued with the operation. Indeed, the Do-17 bombers of Oberst Johannes Fink's KG2, were already airborne in two separate formations when the order was issued, but attempts by radio to recall them were unsuccessful. However, the Bf-110 escorts from ZG26, led by Oberst Joachim Huth, had received the postponement order shortly after becoming airborne but were unable to communicate with the Dorniers because of different radio frequencies. When it became obvious to Huth that KG2 was continuing with its mission, he attempted to show that the start had been delayed by performing erratic manoeuvres with his Bf-110 around Fink's Dornier, while at the same time making hand gestures from the cockpit. Attributing this unusual manoeuvring to over-enthusiasm or high spirits, the display was ignored and the seventy-plus Dorniers continued onwards. Exasperated, Huth returned to his airfield, but KG2 carried on alone and bombed the naval base at Sheerness and the airfield at Eastchurch, during which attacks five Do-17s were shot down by fighters and another five damaged.

We (fighter pilots) had had a very hard day. We spent the night together and drank just half a bottle of champagne, I remember. We were in a bad mood because we had lost friends. So we went to bed with the order to start very early next day, but none of us could sleep, myself included. So I got up, went to the library and picked up a book which I knew. I read, "Whoever weeps, in the world this night, weeps for me", and it moved me very much.

Luftwaffe JG2 ace Paul Temme shot down during the Battle of Britain 13th Aug 1940.Recollections of Paul Temme concerning the evening before his last flight.

Oberst Harry von Bulow's JG2 at Beaumont-le-Roger was another unit which had not received word of the delay and a freie Jagd was undertaken by the Staffein of I. Gruppe to cover a morning raid by elements of KG54 against the airfields at Odiham and Farnborough. During the course of this operation, the Gruppenadjutant of I./JG2, Oblt. Paul Temme, became the first fighter loss of Adlertag when his Bf 109 was damaged by Spitfires and he was obliged to make a forced-landing near Shoreham airfield where he was subsequently taken prisoner. Meanwhile, the Ju-88s of KG54, frustrated by poor weather and the unwelcome attentions of RAF fighters, had aborted the raid.

Some three hours later, similar confusion affected the Bf110s of I./ZG2 which had been ordered to escort other Ju88s from KG54 in a feint towards Portland. By this time, however, KG54 had been made aware of the postponement, but ZG2's 28 Bf110s took off and set out for Portland. Approaching the British coast they found waiting for them not the Ju88s of KG54 they had been briefed to expect but RAF fighters. In the air battle which developed, ZG2 was fortunate to escape with only the loss of one Bf110 and two damaged.

As the day progressed, the weather eventually cleared and Adlertag started in earnest when the first major attack, consisting of three waves of bombers with fighter escort, was launched during the mid-afternoon. In the south-west, Luftflotte 3's Bf 110s of V./LG1 and the Bf 109s of Oberst Max Ibel's JG27 were briefed to escort a formation of Ju88s from LG1 and Ju87s from VIII. Fliegerkorps. In order to protect the bomber formations from the attentions of any defending fighters, a fighter sweep was carried out ahead of the force by Major Gunther Freiherr von Maltzahn's II./JG53. Sweeping in over the coast ahead of the bomber formations they were met by Spitfires of 152Sqn and although some scattered fighting developed, JG53, already low on fuel, was able to withdraw without loss.

On the eastern flank, the Luftflotte 2 force of Ju87s from II./StG1 and IV./LG1, escorted by the Bf109s of Major Gotthard Handrick's JG26, were heading towards their targets; the airfields of Detling and Rochester. Following a well-executed sweep by JG26 which drew the defending fighters of 65Sqn away, Hauptmann Berndt von Brauchitsch's IV./LG1 carried out a successful attack against Detling which caused considerable damage. Despite high expectations to the contrary, other Ju87 units did not do well, II./StG1 ran into navigational difficulties, was unable to locate its target at Rochester airfield and jettisoned its bombs when attacked by the Hurricanes of 56Sqn. II./StG2 attacked the RAF fighter station at Middle Wallop but was intercepted and lost six of its aircraft.

By early evening the daylight attacks were over. Although the airfields of Andover, Detling, Eastchurch and Middle Wallop had been bombed, none except Middle Wallop were fighter airfields and the damage inflicted was not significant to Fighter Command. More serious was the loss of 13 RAF aircraft. In comparison, the Luftwaffe lost nine Bf109s destroyed or seriously damaged in combat out of a total of 44 aircraft destroyed and a further 36 seriously damaged.

On 14 August, Luftflotten 2 and 3 again attacked airfields and communications targets in the south-east of England. Albeit on a lesser scale than those of the previous day, the attacks were again in the form of two thrusts. The first, from Luftflotte 2, began at about noon when some 80 Ju-87s, escorted by all three Gruppen of JG26, headed towards targets at Dover, Folkestone and Hawkinge. Met by no fewer than four squadrons of RAF fighters, an immense dogfight involving some 200 aircraft developed above Dover. While Hptm. Kurt Fischer's I. Gruppe stayed to protect the dive-bombers, the Bf109s of II. and III./JG26, commanded respectively by Hptm. Karl Ebbighausen and Major Adolf Galland, fought it out with the defenders. During the clash between these units, Ju-87s sank a lightship and some Bf109s shot down a number of barrage balloons, neither of these activities contributing to the objective of defeating Fighter Command.

The second thrust of the day was mounted by Luftflotte 3 later in the afternoon. This involved no fewer than nine small raids along a front of some 100 miles of the English South Coast. By dispersing the RAF's fighters in this way, some of the attackers penetrated inland to bomb Middle Wallop and Colerne airfields and Southampton. By the end of the day's fighting Jagdwaffe combat losses amounted to six Bf109E fighters with five pilots killed and one taken prisoner. Although the damage caused to RAF airfields was not significant, what was particularly worrying to Fighter Command was that three of its pilots had been killed.

Meanwhile, at 11.30 hrs, seven Bf110s from the fighter-bomber unit Erp.Gr.210 took off from Denain to carry out two separate attacks on the airfields at Ramsgate and Manston. After refueling at St. Omer, the Bf110s took off again, accompanied by an escort of 7 Bf109s. At Ramsgate, the balloon barrage prevented the attack, so all aircraft continued to Manston. Slipping through the British defences, the Bf110s carried out dive attacks to deliver their 250kg bombs and succeeded in destroying three Blenheims of 600Sqn and two hangars, as well as causing other damage and leaving a large crater in the middle of the airfield. The Gruppe lost two Bf 110s in this attack, one being flown by Uffz. Hans Steding with Gefr. Ewald Schank in the rear cockpit. Just after dropping its bombs, this crew's aircraft sustained a direct hit from one of the airfield's Royal Artillery Bofors anti-aircraft guns which blew off the aircraft's tail. With engines screaming, the remains of the machine cart wheeled across the aerodrome and smashed inverted into the ground, killing the pilot. With remarkable good fortune, however, Schank survived the disintegration of his aircraft and incredulous observers saw that he had been thrown clear of his doomed machine at extremely low altitude. Although he passed out immediately after pulling his ripcord, Schank's parachute opened a mere fraction of a second before he landed, dazed and wounded, on one of the runways. Surrounded by his own unit's bomb bursts and the wreckage of his machine, he started to look for his pilot before being dragged to safety and only fully regained consciousness in Manston's sick ward.

On the evening of the 14th, a forecast of more unfavorable weather suggested that no large scale attack should be launched the following day. Under these circumstances, Goring ordered all his senior commanders to attend a conference at his Karinhall estate where there was to be a detailed inquest into the results of Adlertag. Nevertheless, sortie details for the next day were issued by Luftflotten 2, 3 and 5, primary targets again being Fighter Command airfields which were to be attacked in a series of synchronized raids. However, with the possible exception of Luftflotte 5, there appeared little likelihood of these orders being put into effect because of the predicted weather.

15 August 1940 'Black Thursday'

At first light on 15 August, it seemed that the weather would indeed remain as forecast and that any large-scale daylight operations would not be possible. Even by 10.00 hrs, RAF plotting tables were clear, the only activity reported being a few reconnaissance flights. But the crews of these aircraft reported that the cloud was beginning to clear in the north and west over Britain, and this was accompanied by a rapid improvement in visibility over France. The missions planned for the three Luftflotten were therefore set in motion and shortly before noon, the first major attack took place when 40-plus Ju-87s, protected by a strong fighter escort, attacked the airfields of Hawkinge and Lympne. Considerable damage was caused and pilots from II./JG51 and II. and III./JG26 claimed kills against the Spitfires and Hurricanes which rose to intercept. While these attacks were in progress, the airfield at Manston was strafed by Bf109s which destroyed two of 266Sqn's Spitfires.

In the early afternoon, the Luftwaffe - convinced that the north of England had been stripped of fighters and AA defences in order to reinforce resistance in Southern England - committed the units of Luftflotte 5 to attack targets along the north-eastern coast of England and Scotland. As Bf109s lacked the range to accompany these bombers, escort was provided by 21 Bf110D long-range fighters, but the raid was a disaster. Luftflotte 5 lost more than 20 aircraft and received a mauling so severe that it would take no further part in major daylight operations over Britain.

Further south, Erp.Gr.210 carried out a bold, surprise low-level attack against the airfield at Martlesham Heath. Further formations with heavy fighter escort targeted Eastchurch, Portland, Rochester, Worthy Down, and Middle Wallop. One of the most difficult raids for the defenders to intercept was carried out by 88 Do-17s from KG3 which were to attack the Rochester and Eastchurch airfields in north Kent. As well as being heavily escorted by more than 130 fighters from JG51, JG52 and JG54, the bombers disguised their true objective by flying a dog-leg course and were accompanied by feint attacks. Then, as the bombers approached Deal, more than 60 Bf109s from JG26 swept in near Dover on a freie Jagd patrol. Three RAF squadrons already airborne were diverted to meet this attack and another four squadrons scrambled, but the Jagdflieger protected their charges so effectively that it proved almost impossible for the British fighters to break through the German fighter screen. Only two of the Do-17s were shot down, and the RAF fighters suffered heavily in their attempts to stop this raid.

Shortly after 18.00 hrs Erp.Gr.210 was once again in the air with the Gruppenkommandeur, Hptm. Walter Rubensdorffer leading his Stabsschwarm, closely followed by 1.Staffel under Oblt. Martin Lutz and 2.Staffel under Oblt. Wilhelm-Richard Rossiger. This time their target was Kenley airfield but, owing to a low sun reflecting off an early evening haze, accurate orientation was difficult and soon Rubensdorffer was heard querying his position. Whether JG52's fighter escort had meanwhile missed the rendezvous over France, lost sight of Rubensdorffer's formation in the haze or, as the fighter pilots later claimed, had already withdrawn due to a shortage of fuel, would never become clear, but Rubensdorffer was heard to radio, "We've lost our escort". Then, seeing an airfield below, he radioed again: "There it is! Down we go!" and abruptly banked his aircraft in order to line up for his attack. Although taken by surprise, the other pilots followed him down in a low dive, attacking the hangars and buildings around the airfield with bombs, cannon and machine-guns. An armoury was set on fire, a number of hangars, factories and offices hit, and casualties numbered 68 killed and 192 injured.

But instead of attacking Kenley, the aircraft had struck the nearby airfield of Croydon, and as they withdrew, they were attacked by the Hurricanes of 32 and 111Sqns, which cost the Gruppe seven Bf110s including the whole Stabskette. The losses included the Gruppenkommandeur, Hptm. Rubensdorffer; the Gruppe's second-in-command, Oblt. Horst Feidler, who was captured severely wounded and died later; and the Gruppe's Technical Officer, Lt. Karl-Heinz Koch, who was captured unhurt. In addition, the Staffelkapitan of the 3.Staffel, Lt. Horst Marx baled out and was taken prisoner when his Bf109E escort fighter was shot down by a Hurricane of 32Sqn.

By the end of 15 August the Luftwaffe had flown over 2,000 sorties, destroyed 31 British fighters and damaged another 13. A total of 76 German aircraft was lost although, paradoxically, Jagdwaffe combat losses were relatively few and amounted to just five Bf109 fighter aircraft. Nevertheless, total German losses were the heaviest suffered over England in a single day during the entire Battle, and 15 August became known within the Luftwaffe as 'Black Thursday'.

Meanwhile, at the Luftflotten and Fliegerkorps commanders' conference at Karinhall, Goring criticised the attacks which had been carried out upon such secondary targets as the lightship bombed by Ju-87s the day previously, and questioned the value of continuing the attacks on radar stations. Above all, he found it necessary to remind the commanders of the Luftflotten and Fliegerkorps that their primary objective was to direct attacks exclusively against the RAF, with particular emphasis on the RAF fighter concentrations around London. More efficient use was to be made of the Bf110 in deep penetration missions, and in view of the losses suffered by the Ju-87 units, each Stukagruppe would in future be escorted by three Jagdgruppen.

"The fighter escort defences of our Stuka formations must be re-adjusted, as the enemy is concentrating his fighters against our Stuka formations. It appears necessary to allocate three fighter Gruppen to each Stuka Gruppe; one of these fighter Gruppen remains with the Stuka’s and dives with them to the attack; the second flies ahead over the target at medium altitude and engages the fighter defences; the third protects the whole attack from above. It will also be necessary to escort Stukas returning from the attack over the Channel. "

Reichsmarschall Hermann Goring, Karinhall Conference, 15 August 1940: Paragraph 1 on an address to Luftflotte Senior Staff.

Despite the heavy bomber losses of the previous day, the Luftwaffe's bombers were out in force again on the 16th and once more the targets were RAF airfields. Throughout the day these attacks, accompanied by numerous fighter escorts - and often, preceded by fighters sweeping ahead of the bombers in freie Jagd sweeps - were aimed at Biggin Hill, Brooklands, Dover, Gosport, Hornchurch, Lee-on-Solent, Tangmere, Westhampnett and West Mailing. Although Goring had queried the point of continuing the attacks on RDF stations, the one at Ventnor was attacked again after just coming back into service following the earlier attack on the 12th. This time the station was off the air for a further seven days. In the early evening further bombing attacks were carried out against Brize Norton, Farnborough and Harwell, while Manston airfield was again strafed by eight Bf109s which destroyed a 65Sqn Spitfire, a 600Sqn Blenheim and damaged another. Manston was situated close to the coast and lacked any natural cover in which to disperse its fighters. As well as being subjected to carefully planned strafing attacks, any German aircraft with bombs or ammunition remaining was likely to use the airfield as a target of opportunity before heading back over the Channel.

At the end of the day's fighting, Jagdwaffe combat losses almost doubled those of the 15th, with 12 fighters lost and a further eight damaged. Notable losses included the Staffelkapitan of 4./JG3, Hptm. Alfred Muller who was wounded and rescued from the sea by the Seenotdienst, and the Gruppenkommandeur of II./JG26, Hptm. Karl Ebbighausen who was killed when his aircraft was shot down by Spitfires off Dover.

18 August 1940

Following the intense action of the preceding two days, no daylight missions were flown on the 17th and apart from a few reconnaissance flights, the morning of the 18th was also quiet, giving no indication that the day would result in some of the fiercest fighting of the Battle. But the respite was brief and shortly after midday, Dover RDF station reported the greatest build-up of enemy forces yet seen as the Luftwaffe again focused its attention on the important airfields at Kenley, Biggin Hill, Hornchurch, and North Weald, upon which the fighter defences of south-eastern England hinged. Bombing and dive-bombing of these airfields was to be carried out by KG1, KG2, KG53 and KG76, with further dive-bombing attacks by St.G3 and St.G77 due to take place against the RDF station at Poling and airfields in West Sussex and Hampshire. Fighter escort and diversionary fighter sweeps in support of the attacks were to be provided by JG3, JG26, JG27, JG51, JG52, JG53, JG54 and ZG26.

The first attacks were carried out by Luftflotte 2's KG1 and KG76 against Biggin Hill and Kenley respectively. In addition, operating some 25 miles ahead of the incoming bombers, the Bf109s of JG26 and JG53 swept over the Kent and Sussex countryside on a freie Jagd patrol. In Galland's absence, III./JG26 was led on this occasion by the Staffelkapitan of 9./JG26, Oblt. Gerhard Schopfel and, as the Gruppe crossed the coast shortly after 13.00 hrs, Schopfel saw below him the Hurricanes of 501Sqn climbing in close formation. Deciding to attack the rearmost aircraft, he indicated to his pilots that they should cover him from above and began to stalk the British fighters. By carefully biding his time and keeping his aircraft between the glare of the sun and his intended victims, Schopfel was able to carry out a lone attack on the rear of the formation and, achieving complete surprise, shot down four Hurricanes in two minutes. At the time, this feat was unprecedented but, according to another German pilot flying with Schopfel, he would have continued to destroy more of the enemy aircraft but had to break off due to oil from one of his victims obscuring his windscreen.

The plan for KG76's attack against Kenley called first for Ju-88s from II./KG76 to dive-bomb the airfield hangars and buildings. This attack was to be followed by the Do-17s of I. and II./KG76 which were to bomb the landing ground and ground defences, after which 9./KG76 was to follow up with a low-level attack to destroy any remaining buildings. However, due to cloudy conditions, the careful timing of the attack was disrupted. The bombers failed to rendezvous with their assigned fighter escort and 9./KG76, which should have been last over the target, arrived first. Running into the full force of the airfield defences, the Staffel lost four of its nine bombers. Nevertheless, the combined attacks by KG76 put Kenley out of action for two hours.

While the Kenley attack was in progress, Major Martin Mettig's JG54 escorted 60 He-111s of KG1 in a high-level attack against Biggin Hill. Arriving virtually unmolested by the defending British fighters, the Henkels bombed the airfield but damage to vital areas was minimal. Most of the bombs fell onto the open areas of the airfield or in the woods beyond and the airfield was able to continue operating.

Over the Channel, 16 Bf 109s from 2. and 3./JG52 led by Oblt. Wolfgang Ewald waited to provide cover for the returning bombers but, at around 14.00 hrs having completed their assignment without encountering any British fighters, they carried out instead a freie Jagd sweep over Kent. Arriving over Manston at approximately 14.20 hrs, they caught the Spitfires of 266Sqn on the ground while refueling. Carrying out two rapid strafing attacks on the parked aircraft, they destroyed a Hurricane from 17Sqn, two Spitfires and severely damaged another six Spitfires before making good their escape. RAF groundcrews, servicing the aircraft in the open, suffered one man killed and 15 injured.

At approximately 14.30 hrs, Luftflotte 3 mounted the second major attack of the day when, in concert with a freie Jagd fighter sweep mounted by JG2, the Ju-87s of St.G3 and St.G77 attacked the RDF station at Poling and south coast airfields. The Stukas of I./St.G 3, escorted by the Bf109s of Major Eduard Neumann's I./JG27 struck the Gosport naval airfield at Lee-on-Solent while those of I./St.G77, escorted by Hptm. Werner Andres's II./JG27 hit the Coastal Command airfield at Thomey Island. Further to the east, the Ju-87s of II./St.G77 with their escort from Hptm. Joachim Schlichting's III./JG27 attacked the naval airfield at Ford while the force from III./St.G77, escorted by Hptm. Albert Blumensaat's I./JG53, bombed Poling RDF station. All the airfields and Poling radar station suffered considerable damage, but as the Ju-87s formed up and withdrew, they were attacked by Spitfires and Hurricanes from three RAF fighter squadrons and no less than 16 of the Ju-87s were shot down plus two damaged beyond repair.

Shortly after 17.00 hrs, the day's third attack commenced when, again conducted by Luftflotte 2, 100-plus Dorniers and Heinkels from KG2 and KG53 set out to attack the airfields at Hornchurch and North Weald, escorted by some 140 Bf109s and Bf110s from JG3, JG26, JG51, JG54 and ZG26. Met by the determined opposition of eight squadrons of RAF fighters and hampered by increasing cloud over their assigned targets, both formations were forced to abandon their attacks and turn back. Re-crossing the English coast, KG53, which had found North Weald covered in cloud, bombed Shoeburyness on its way home and KG2, also aborting its attack on Hornchurch, bombed Deal and hit the Royal Marine barracks.

Thus ended a day which is recognised as one of the hardest fought of the Battle. Fighter Command had 73 fighters put out of action and a further 62 British aircraft were destroyed or damaged during the attacks on airfields. Luftwaffe combat losses, while not as high as those on the 15th, involved 61 aircraft shot down including a total of 15 Bf109s with a further five damaged. JG27 suffered the highest casualties with six aircraft lost and three pilots killed, two taken prisoner and one rescued from the sea by the Seenotdienst. JG3 suffered the next highest casualties with three aircraft lost and three damaged, one of which was written-off. Of the pilots, the Staffelkapitan of 2./JG3, Oblt. Helmut Tiedmann was captured, two from II. Gruppe were wounded, one of whom later died, and two from III. Gruppe were also killed in action. JG51's losses included Lt. Hans-Otto Lessing and the Staffelkapitan of 5.Staffel, Hptm. Horst Tietzen.

The Karinhall Conference of 19 August 1940

After reviewing the results of a week of ferocious fighting which had concluded with the bitter battles and heavy losses of the 18th, it became clear to Goring that further directives were needed to ensure the swift destruction of the enemy air force. On 19 August, for the second time in a week, he therefore summoned his commanders to attend a meeting at Karinhall. Highest losses of all had been suffered by the Stukagruppen which, in the previous two weeks, had carried out fourteen major attacks but had lost 39 aircraft. With the catastrophic loss of an additional 18 aircraft on 18 August, ObdL decided that in order to prevent their complete destruction, the Stukagruppen were to be withdrawn until such time as the RAF had been defeated.

Confronting his Jagdwaffe Kommodore with the heavy bomber losses, Goring complained that the fighters lacked aggressiveness and refused to acknowledge that the main weakness lay in faulty planning and technical shortcomings which rendered the Ju-87s and Bf110s particularly vulnerable to fighter attack. Instead, Goring blamed the fighter pilots for the high Ju-87 and Bf110 losses, criticised the standard of escort and protection, and ordered a complete reorganisation and redeployment of the Jagdgeschwadern.

Goring also believed that the overall morale and fighting spirit of the Jagdwaffe would improve through the appointment of younger officers to positions of command. At this time, many of the Gruppen were commanded by officers who had been pilots in the First World War and Goring considered them either too old or lacking the necessary aggressive spirit. Accordingly, several Jagdgeschwader Kommodore were dismissed and replaced by such younger pilots as Galland, Trautloft, Lutzow and Schellmann, all of whom had proved successful on operations. The fighter force was the first branch of the Luftwaffe to be so rejuvenated and, as a general rule, age limits would henceforth be 32 for a Geschwaderkommodore, 30 for a Gruppenkommandeur and 27 for a Staffelkapitan. The result of this change was that in most cases the commander of a Geschwader, a Gruppe or a Staffel was also the most skilful pilot and the one with the greatest number of victories.

Contrary to what has previously been written, Goring did not at this time order the majority of the fighter force to carry out close escort missions. While the bomber crews attached extraordinary importance to close escort and demanded the allocation of more fighters to this role, it would have been a purely defensive measure not in keeping with the aggressive character of the Jagdwaffe. Such an order would have tied the fighters so closely to the bombers that they would have been deprived of the freedom to seek out and destroy Britain's fighter force, a task which was, after all, ObdL's primary objective. Goring therefore directed that commanders of fighter units should, as far as possible, be given a completely free hand in the conduct of operations, stating: "Only part of the fighters are to be employed as direct escorts to our bombers. The aim must be to employ the strongest possible fighter forces on free-lance operations, in which they can indirectly protect the bombers, and at the same time come to grips under favorable conditions with the enemy fighters."

However, these measures were accompanied by two further demands, the first of which concerned the twin-engined Bf110 Zerstorer units. When the Bf110 units were first formed, it was intended to use them as long-range fighters, but the course of the Battle so far had confirmed that the Bf110 was unable to give a good account of itself. Despite its concentrated firepower and defensive weapons, in combat with British fighters it was inevitably singled out for attack and forced to fly in defensive circles. The Bf110s therefore had to rely on Bf109s coming to their assistance or else escape as best they could. In future, then, when used as escort fighters, the Bf110s were themselves to be provided with a fighter escort of Bf109s. The second demand was that specially designated fighter units should be made available to provide protection over the Channel for fighter, bomber and destroyer aircraft returning from operations over England. Thus the demand to simultaneously employ the strongest number of aircraft on freie Jagd sweeps, provide more fighters as close escort, and yet more to meet returning aircraft, placed an excessive strain on resources due to the number of aircraft and pilots all such tasks required.

Change of unit commanders in the Jagdwaffe between August and October 1940

The following tables show the changes which took place in the Jagdwaffe between July and December 1940. It should be noted that not all these changes resulted from a programme to replace the older commanding officers with younger men. Some changes resulted from promotions, i.e. when a replacement was required for a Gruppenkommandeur promoted to Geschwaderkommodore or as a result of combat losses.

LUFTFLOTTE 2 Jagfliegerfuhrer 2 Unit Previous commander Later commander Date of take-over LUFTFLOTTE 2 Jagfliegerfuhrer 2 Stab/JG3 Obstlt. Carl Viek Gunther Lutzow 22-Aug-1940 I./JG3 Hptm. Gunther Lutzow Hptm. Hans von Hahn* 22-Aug-1940 *(Lutzow became Kommodore) II./JG3 Hptm. Erich von Selle Hptm. Erich von Selle (no change) III./JG3 Hptm. Walter Kienitz Hptm. WIIhelm Balthasar 8-Aug-1940 Stab/JG26 Gotthard Handrick Adolf Galland 22-Aug-1940 I./JG26 Hptm. Kurt Fischer Hptm. Rolf Pingel 22-Aug-1940 II./JG26 Hptm. Karl Ebbighausen Hptm. Erich Bode 16-Aug-1940 *(Ebbighausen was killed on 16 Aug 40) III./JG26 Adolf Galland Gerhard Schopfel 22-Aug-1940 *(Galland became Kommodore) Stab/JG51 Oberst Theo Osterkamp Obstlt. Werner Molders 27-Jul-1940 I./JG51 Hptm. Hans-Heinrich Brustellin Hptm. Hermann-Friedrich Joppien 1-Oct-1940 II./JG51 Hptm. Gunther Matthes Hptm. Gunther Matthes (no change) III./JG51 Hptm. Hannes Trautloft Hptm. Walter Oesau 25-Aug-1940 *(Trautloft became Kommodore of JG54) Stab/JG52 Major Hubertus Merhardt von Bernegg Major Hanns Trubenbach Aug-1940 I./JG52 Hptm. Siegfried von Eschwege Hptm. Wolfgang Ewald 27-Aug-1940 II./JG52 Hptm. von Hans-Gunter Kornatzki Hptm. WIIhelm Ensslen 27-Aug-1940 III./JG52 Major Alexander von Winterfeldt Major Alexander von Winterfeldt (no change) *Gruppe transferred to Germany from Coquelles on 25 Aug 40 because of heavy losses Stab/JG54 Major Martin Mettig Major Hannes Trautloft 25-Aug-1940 I./JG54 Hptm. Hubertus von Bonin Hptm. Hubertus von Bonin (no change) II./JG54 Hptm. Otto Winterer Hptm. Dietrich Hrabak 26-Aug-1940 III./JG54 Hptm. Fritz Ultsch Oblt. Gunther Scholz (acting) 5-Sep-1940 *(Ultsch was killed on 5 Sep 40) I./JG77 Hptm. Johannes Janke (became IV./JG51 on 25 Aug 40) I.(J)/LG2 Oblt. Herbert Ihlefeld Oblt. Herbert Ihlefeld (no change) LUFTFLOTTE 3 Jagdfliegerfuhrer 3 Stab/JG2 Oberst Harry von Bulow-Bothkamp Major Wolfgang Schellmann 3-Sep-1940 *(Major Helmut Wick took over on 20 Oct 40) I./JG2 Major Hennig Strumpell Hptm. Helmut Wick 10-Sep-1940 II./JG2 Major Wolfgang Schellmann Hptm. Karl-Heinz Greisert 3-Sep-1940 III./JG2 Major Erich Mix Oblt. Otto Bertram 15-Sep-1940 *(Hptm. Hans 'Assi' Hahn* took over on 1 Oct 40) Stab/JG27 Obstlt. Max Ibel Major Bernhard Woldenga 15-Oct-1940 I./JG27 Major Eduard Neumann Major Eduard Neumann (no change) II./JG27 Hptm. Werner Andres Hptm. Wolfgang Lippert 1-Oct-1940 III./JG27 Hptm. Joachim Schlichting Hptm. Max Dobislav 18-Sep-1940 Stab/JG53 Obstlt. Hans-Jurgen von Cramon-Traubadel Major Gunther von Maltzahn 10-Oct-1940 I./JG53 Major AlbertBlumensaat Hptm. Hans-Karl Meyer Aug-1940 II./JG53 Hptm. Gunther von Maltzahn Hptm. Heinz Bretnutz 10-Oct-1940 *(von Maltzahn became Kommodore) III./JG53 Hptm. Hans-Joachim Harder Major Wolf Dietrich Wilcke 13-Aug-1940 *(Harder was killed on 13 Aug 40) LUFTFLOTTE 5 X.Fliegerkorps Stab/JG77 Obstlt. Eitel-Fritz Roediger von Manteuffel Major Bernhard Woldenga 3-Nov-1944 II./JG77 Hptm. Karl Hentschel Hptm. Karl Hentschel (no change) * Hans von Hahn (born on 7 Aug 1914 in Frankfurt) should not be confused with Hans 'Assi' Hahn (born on 14 Apr 1914 in Gotha)

20 August to 6 September 1940 - The Battle of the Airfields

"To sum up: we have reached the decisive period of the air war against England. The vital task is to turn all means at our disposal to the defeat of the enemy Air Force. Our first aim is the destruction of the enemy's fighters. If they no longer take to the air, we shall attack them on the ground, or force them into battle by directing bomber attacks against targets within the range of our fighters. At the same time, and on a growing scale, we must continue our activities against the ground organization of the enemy bomber units. Surprise attacks on the enemy aircraft industry must be made by day and night. Once the enemy Air Force has been annihilated, our attacks will be directed as ordered against other vital targets".

Directives issued by Reichsmarschall Hermann Goring, Second Karinhall Conference, 19 August 1940

Continuing adverse weather during the period 20-23 August again restricted Luftwaffe daylight operations and brought a period of relatively reduced activity, although the 20th is notable as the There were only a few of us who had not yet had to ditch in the Channel with a shot-up aircraft or stationary propeller.

Oblt. Hans van Hahn of I./JG3 commenting on the ever-present obstacle facing the pilots of the Jagdwaffe - the English Channel

It was therefore reasoned that a tactical advantage would be gained by transferring the majority of the Jagdgeschwadern of Luftflotte 3 to Kesselring's Luftflotte 2 in the Pas de Calais area. However, while this decision increased to 18 the number of Jagdgruppen available to Luftflotte 2 and made more fighters available to meet Goring's latest directive, the scarcity of fighters left to Luftflotte 3 would later lead to escalating losses, especially amongst the Bf110 Zerstorergeschwader during the September raids.