Battle of El Guettar part of Tunisia Campaign

Date: March 23 - April 7, 1943

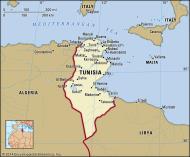

Location: El Guettar, Tunisia

Result: US victory

Belligerents: United States - Nazi Germany and Italy

Commanders and leaders:

United States Army General George Patton

Axis Forces: Nazi Germany Jürgen von Arnim and Italy Giovanni Messe

Casualties and losses:

USA: 35-55 tanks lost 4,000-5,000 killed or wounded

Axis Forces: 40+ tanks lost 4,000-6,000 killed or wounded in 3 weeksThe Battle of El Guettar was a World War II battle that took place during the Tunisia Campaign, fought between elements of the Army Group Afrika under Jürgen von Arnim and U.S. II Corps under Major General George Patton in south-central Tunisia. It was the first battle in which U.S. forces were able to defeat the experienced German tank units, but the followup to the battle was inconclusive.

Background

U.S. II Corps had been badly mauled in their first encounter with the German-Italian forces in Tunisia in a series of battles that culminated in the disastrous Battle of the Kasserine Pass in late February 1943. Erwin Rommel, poised on the threshold of a complete tactical victory, turned from the battle to return to his eastward-facing defenses at the Mareth Line when he heard of the approach of Bernard Montgomery's British 8th Army. Thus the battle concluded with the U.S. forces still in the field, but having lost ground and men, and with little confidence in some key commanders.

The American command reacted to their failure against the German forces with a prompt and sweeping series of changes in command, discipline, and tactics. A major change was the adoption of more flexible artillery communications, allowing all batteries within range of a target to respond to a single call for fire. Previously each battery could fire only on the direct command of its dedicated observers, spread out over the lines and using different frequencies to communicate back to the battery. Also, large units were kept massed rather than being broken up into smaller, unsupported elements as had been done under Fredendall. Coordination with air support was improved but did not reach satisfactory levels until later in the war.

On 6 March 1943, George Patton took command of the U.S. II Corps from Lloyd Fredendall, who had been in command before and during the Kasserine engagement. His first move was to organize his U.S. II Corps for an offensive back toward the Eastern Dorsal chain of the Atlas Mountains. This, if successful, would threaten the right rear of the Axis forces defending the Mareth Line facing Montgomery's 8th Army and ultimately make their position untenable.

On 17 March the U.S. 1st Infantry Division moved forward into the almost abandoned plains, taking the town of Gafsa and starting to set it up as a forward supply base for further operations. On the 18th the 1st Ranger Battalion led by Colonel William O. Darby pushed ahead, and occupied the oasis of El Guettar, again meeting with little opposition. The Italian defenders instead retreated and took up positions in the hills overlooking the town, thereby closing the mountain pass (of the same name) leading south out of the interior plains to the coastal plain. Another operation by the Rangers took one of the Italian positions and 700 prisoners on the night of 20 March, after scaling a sheer cliff and passing ammunition and equipment up hand-over-hand. They were now in an excellent position for an offensive.

Battle

A map 30 Jan to 10 Apr 1943 Battle of El Guettar Tunisia

The Axis army commanders had become aware of the U.S. movements and decided that the 10th Panzer Division should settle them. Rommel had flown to Germany before the battle, leaving von Arnim in control of the newly-named Army Group Africa. Von Arnim held Rommel's opinion on the low quality of the U.S. forces and felt that a show of force would be enough to clear them from the Eastern Dorsals again.

At 06:00 on 23 March, fifty tanks of Broich's 10th Panzer emerged from the pass into the El Guettar valley at 34°20′12″N 8°56′53″E / 34.33667°N 8.94806°E / 34.33667; 8.94806, followed by Marder tank destroyers and panzergrenadiers. The Germans quickly overran front line infantry and artillery positions. Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen, Sr., commanding U.S. 1st Infantry Division, was threatened when two tanks came near his headquarters, but he shrugged off suggestions of moving, "I will like hell pull out, and I'll shoot the first bastard who does."[1]

German efforts took a turn for the worse when they ran into a minefield. When they slowed to clear the field, U.S. artillery and anti-tank guns opened up on them, including 31 potent M10 tank destroyers which had recently arrived. Over the next hour, 30 of the 10th Panzer's tanks were destroyed, and by 09:00 they retreated from the valley.

A second attempt was made starting at 16:45, after waiting for the infantry to form up. Once again the U.S. artillery was able to seriously disorganize the attack, eventually breaking the charge and inflicting heavy losses. Realizing that further attacks were hopeless, the rest of the 10th dug in on hills to the east or retreated back to German HQ at Gabès.

Patton attacks

On 19 March, the British 8th Army launched their attack on the Mareth Line, at first with little success. However, on 26 March, a force sent via an outflanking inland route arrived to the north of the line, and the Mareth defenses became untenable. A full retreat started to a new line set up at Wadi Akarit, north of Gabès at 33°53′3″N 10°5′33″E / 33.88417°N 10.0925°E / 33.88417; 10.0925. This made the U.S. position even more valuable, since the road through El Guettar led directly into Gabès.

Over the next week the U.S. forces slowly moved forward to take the rest of the interior plains and set up lines across the entire Eastern Dorsals. German defenses were heavy, and the progress was both slow and costly. However by 30 March they were in position for an offensive south from El Guettar. In order to start a breakout, the two original Italian strongpoints on Hill 369 34°14′29″N 9°7′16″E / 34.24139°N 9.12111°E / 34.24139; 9.12111 (Hill 369) and Hill 772 34°12′7″N 8°59′36″E / 34.20194°N 8.99333°E / 34.20194; 8.99333 (Hill 772) had to be taken, one after the other.

The U.S. plan involved the U.S. 1st and 9th Infantry Divisions, and one "Combat Command" (1/3rd) of the U.S. 1st Armored Division, collectively known as "Benson Force". This force attacked Hill 369 on the afternoon of 30 March but ran into mines and anti-tank fire, losing 5 tanks. The tanks were removed, and the 1st and 9th attacked again the next day at 06:00, moving up and taking several hundred prisoners. However an Italian counterattack drove them back from their newly gained positions, and by 12:45 they were back where they started with the loss of 9 tanks and 2 tank destroyers. A further attempt the next day on 1 April also failed, after barely getting started.

At this point Patton received orders to start the attempt on Hill 772, even though Hill 369 was still under Italian control. The 9th was moved to Hill 772, leaving the 1st on Hill 369. By 3 April, the 1st had finally cleared Hill 369, but the battle on Hill 772 continued. The Italian commander, General Messe, then called in support from the German 21st Panzer Division, further slowing progress. The tempo of the operations then slowed, and the lines remained largely static.

On 6 April, the British 8th Army once again overran the German lines, and a full retreat started. On the morning of 7 April, Benson Force moved through the positions held by the 1st and 9th, and raced down the abandoned El Guettar-Gabès road, where it met the lead elements of the 8th Army at 17:00.

Aftermath

With the last Axis line of defense in the south of Tunisia broken, they made a run to join the other Axis forces in the north. Tunisia fell to the Allies in early May.

The results of the El Guettar operations were mixed. The U.S. showed they were able to fight the Germans successfully in a defensive operation during the opening stages but also demonstrated a lack of power when starting offensive operations of their own.

The Allied landings in North Africa

Basil Liddell Hart - The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

When the amphibious landings took place on November 8, 1942, the Americans had achieved surprise too fully, throwing their friends and helpers into confusion. The French whom they had enlisted to their cause were caught unready to aid them effectively, and the landings initially met resistance, albeit less at Algiers than at Oran or Casablanca. On the Atlantic coast, the main landing was made at Fedala (now Mohammedia), 15 miles (24 km) northeast of Casablanca. Hesitation and confusion among the French defenders meant that the invading troops were safely ashore before the landings could be opposed in any serious way. Difficulty arose in extending the beachhead, however, and by the third day of the operation the outlook was gloomy. The situation in Casablanca and on the Atlantic coast as a whole was soon decisively changed by favourable political developments in Algiers. On the afternoon of November 10, Gen. Charles-Auguste Noguès, the French commander in chief in Morocco, heard indirectly that the French authorities in Algiers, now personally headed by Darlan, had issued an order to stop fighting. Noguès was prompt to act on that report and ordered his own subordinate commanders to cease active resistance, pending an armistice that would be arranged the following morning.

The U.S. landings at Oran met somewhat stiffer opposition. On the second day little progress was made, as French resistance stiffened, and a French counterattack on the flank of the Arzew beachhead threatened the whole plan of operations in that theatre. The landings at Algiers ran a smoother and shorter course, thanks largely to Mast and his confederates. No serious resistance was met anywhere, except when the Allies tried to force an early entry into the harbour. Half an hour after midnight on November 8, Murphy notified Juin that overwhelmingly strong forces were about to land and urged him to issue orders that they were not to be resisted. He stressed that they had come on the invitation of Giraud to aid France in liberating itself. Juin, unready to accept Giraud’s leadership, replied that the appeal must be submitted to Darlan, who happened to be in Algiers visiting his seriously ill son. Summoned urgently by telephone to Juin’s villa, Darlan agreed to send a radio message to Pétain requesting authorization to deal with the situation on Pétain’s behalf. In the meantime, Darlan issued orders to the French troops and ships in the Algiers area to cease firing. Although that order did not apply to the Oran or Casablanca areas, Darlan authorized Juin to arrange a settlement for the whole of North Africa. Moreover, it was agreed early in the evening that control of Algiers should be transferred to the Americans at 8:00 PM and that the Allies should have the use of the harbour from first light on the morning of November 9. The afternoon of November 9 saw the arrival of Clark and British Gen. Kenneth Anderson, the latter of whom assumed command of the Allied First Army for the advance into Tunisia. Giraud had arrived a little earlier but found little support among his countrymen.

Pétain announced on November 10 that all authority in North Africa had been transferred from Darlan to Noguès. He had preceded this with a secret message to Darlan to say that he was disavowing him under German pressure and against his own wishes. Such double-talk was necessitated by the perilous situation in France, but it left French commanders in North Africa confused. Hitler resolved that uncertainty the following day, when he set aside the Franco-German Armistice of 1940 and ordered his forces into the hitherto unoccupied part of France. Southern France was speedily overrun by German mechanized units, with six Italian divisions invading from the east.

German planes began to arrive at an airfield near Tunis on the afternoon of November 9, and by the end of November there were 15,000 Germans in Tunisia, supported by about 100 tanks. Some 9,000 Italian troops had also arrived, largely by road from Tripoli. Those forces were almost insignificant when compared with the size of the invading Allied armies, and they would have had a slim chance of resisting an attack if the Allied command had developed an advance more rapidly than it did. Meanwhile, Darlan had received a second clandestine message from Pétain, wherein the Vichy leader reaffirmed his confidence in Darlan and emphasized that he himself was in contact with Roosevelt. Darlan was able to secure a working agreement with the Allies, including recognition of Giraud. The Franco-American discussions at a conference on November 13 were expedited by a threat from Clark that he would arrest the French leadership and implement martial law if a settlement could not be reached. The agreement was promptly endorsed by Eisenhower, who had come to appreciate, as Clark had, that Darlan was the only man who could bring the French round to the Allied side. Darlan subsequently made a detailed agreement with Clark for cooperative action and made the key port of Dakar, together with its air bases, available to the Allies. On December 24, 1942, Darlan was assassinated by an anti-Vichy radical, an event that ultimately cleared the way for de Gaulle’s ascent. The assassin was promptly tried by court-martial on Giraud’s orders and executed. On December 27 it was announced that the French leaders had agreed to choose Giraud to succeed Darlan as high commissioner.

François Darlan

Without Darlan’s assistance, the Allied campaign in northwestern Africa would have faced significantly more challenges. Although the French troops in North Africa were widely spread out, they numbered nearly 120,000 and could have provided formidable opposition had they continued to resist the Allies. The only important matter in which Darlan’s cooperation failed to achieve the desired effect was the liberation and relocation of the main French fleet from Toulon to North Africa. The commander at Toulon, Adm. Jean-Baptiste Laborde, hesitated in responding to Darlan’s request because it was not accompanied by Pétain’s authorization, and a special emissary sent by Darlan was intercepted by the Germans. The delay forfeited the fleet’s chance of breaking out, but on November 27, 1942, the French managed to frustrate the German attempt to capture it by scuttling more than 70 ships.

Map Tunisia, November 1942–May 1943

Anderson’s planned offensive against Tunis did not begin until November 25, 1942, and in the weeks following the initial Allied landings, the slender German strength there had been trebled. The German reinforcements included five new Pz. VI (Tiger) tanks. The massively armoured tanks, which sported a devastating 88-mm gun, were a closely guarded secret, but Hitler had hoped to combat test a small number of them against the Allies. By December 5 the Allied advance had been checked roughly a dozen miles (20 km) short of Tunis. On December 9, 1942, Gen. Jürgen von Arnim relieved Gen. Walther Nehring and took supreme command of Axis forces in Tunisia (now christened the Fifth Panzer Army). With the arrival of additional reinforcements, Arnim proceeded to expand the perimeters around Tunis and Bizerte into a single bridgehead. Allied intelligence estimated that Axis forces in mid-December included about 25,000 fighting troops and 10,000 administrative personnel, with 80 tanks—an excessive estimate. The Allies’ own effective fighting strength numbered close to 40,000 (some 20,000 British, 12,000 American, and 7,000 French), while their total strength was much larger, owing to their more-extensive logistical and administrative structures.

Tunisia

Delays in the buildup, partly due to bad weather, led Anderson to postpone the renewal of the offensive until December 24. Preparatory attacks proved disappointing, however, and when the day came, Eisenhower and Anderson decided to suspend the offensive. The Allies had lost the race for Tunis, but that tactical failure would yield an enormous strategic victory; Hitler and Mussolini were thus induced to pour significant resources into Tunisia at a time when those assets were desperately needed elsewhere.

Rommel’s final offensive in Africa

The campaign of 1943 opened with a German counterstroke that stunned the Allies. It came just when their two armies—the Anglo-U.S. First Army in the west and the British Eighth Army in the east—seemed about to crush the Axis forces between them. The Axis command aimed to forestall that danger by dislocating both forces opposing them. By now reinforcements sent to Tunis had been built up into an army under Arnim, while the remnant of Rommel’s army was acquiring equipment and fresh troops as it neared the supply ports in its westward retreat. Profiting from that temporarily favourable turn, Rommel determined to exploit the “interior lines” in Napoleonic style, utilizing his central position between the two converging Allied armies to strike and cripple them separately and successively. If he could neutralize the First Army, he would have both hands free to tackle the Eighth Army, which had become thinned out as its lines of supply had lengthened.

The U.S. II Corps (which included a French division) was the immediate target of the German attack. The offensive was launched on a front 90 miles (145 km) wide but was focused on the three mountain passes near Gafsa, Fāʾiḍ, and Fondouk. Those passageways were so narrow that the defenders felt secure, but at the end of January 1943 the 21st Panzer Division made a sudden dash at Fāʾiḍ Pass, overwhelming the French garrison before American support could arrive. That led the Allied commanders to expect a follow-up attack, but they expected that it would come at Fondouk. As Gen. Omar Bradley, the commander of the II Corps, remarked in his memoirs, “This belief came to be a near-fatal assumption.”

On February 14, 1943, the real blow came, starting with a fresh assault from the Fāʾiḍ Pass. Gen. Heinz Ziegler, at the head of the 21st Panzer Division, turned the left flank of the American forces there and destroyed more than 100 U.S. tanks. Rommel urged Ziegler to drive on during the night and exploit the success to the fullest, but Ziegler paused for two days while he waited for Arnim’s authorization to continue. The Americans rallied at Sbeitla (Sufetula), and Ziegler drove them back again, until they made a more-determined stand at the Kasserine Pass.

Meanwhile, Rommel led a panzer detachment on a southerly thrust through Gafsa, driving 50 miles (80 km) by February 17 and capturing the American airfields at Thelepte, to the southwest of Kasserine. Alexander, who had just taken charge of both Allied armies in Tunisia, arrived at Kasserine to find the forces there in disarray, with no coordinated plan of defense and an unclear command structure. Rommel hoped to exploit the confusion and panic with a combined drive using all available mechanized forces through Tébessa, an American logistics and communication hub. Arnim was unwilling to embark on such a venture, so in desperation Rommel appealed to Mussolini. It was not until early on February 19 that Rome authorized a continuation of the thrust, but Rommel was ordered to strike northward to Thala, instead of northwestward to Tébessa. Rommel argued that such an attack was “far too close to the front and bound to bring us up against strong enemy reserves,” an appraisal that was soon proven accurate. Indeed, Alexander was well prepared to meet an attack at Thala. He had arrayed his armour in a strong defensive posture, and British reserves from the north were rushed down to reinforce the position. The Americans, too, had collected in strength on the line of approach to Thala, and they held on so stubbornly to the Kasserine Pass that the Germans did not break through it until the evening of February 20. The Germans drove into Thala the next day, but they were quickly pushed out by the British reserves that had now arrived there. On February 22 Rommel, realizing that his chance had passed, broke off the attack and began a gradual withdrawal.

Arnim mounted an attack against the Allied positions facing Tunis, but that too-direct approach both failed in its immediate goals and held up divisions that Rommel needed for his intended second stroke against Montgomery. Until February 26, 1943, Montgomery had had only one division facing the Mareth line, but his staff worked feverishly to reinforce the defenses before the Axis blow came. By March 6, when Rommel attacked, his chance of striking with a superior force had vanished. Montgomery had quadrupled his strength: he now had 400 tanks and more than 500 antitank guns in position. Rommel’s attack was brought to a standstill by the afternoon, and the Germans lost 50 tanks, a serious handicap for the next phase of the campaign. By then the Afrika Korps had also lost Rommel, who was ordered back to Europe, sick and frustrated.

The final Allied assault and the German collapse

On March 17, 1943, the Allied offensive opened with an attack by the U.S. II Corps, now under Patton. It was aimed at the Afrika Korps’ line of retreat up the coast from the Mareth Line to Tunis, but the advance was first cautiously slow and then definitely checked in the mountain passes that provided the approach to the coastal strip. The Allies’ ultimate victory owed more to the enemy’s misjudged offensive efforts than to their own assaults, with their greatest opportunities coming only after the Germans had overstretched themselves.

The Eighth Army’s attack on the Mareth Line was launched on the night of March 20, 1943, with a frontal blow that was intended to make a gap through which the armoured divisions could pour. At the same time, the New Zealand Corps made a wide outflanking march toward el-Hamma in the Germans’ rear, with the aim of pinning down the enemy’s reserves. After three days, the frontal attack had failed to make an adequate breach, so Montgomery sent the 1st Armoured Division to bolster the New Zealanders’ threat to the enemy’s rear. Even then, the British attacks were checked by the German defenses at el-Hamma. Thus, although the Germans had been forced to abandon the Mareth Line, they were able to withdraw in an orderly fashion and take up a new defensive position on the Wādī al-ʿAkārīt, north of Gabès.

In the early hours of April 6, the Eighth Army attacked the Wādī al-ʿAkārīt under cover of darkness and achieved a breakthrough. When daylight came, the Germans checked the advance, but two of their three attenuated panzer divisions were now absorbed in holding off an American push east of Gafsa. The Germans were without sufficient resources to maintain their resistance, and the following night they broke away and retired rapidly up the coast toward Tunis. On April 8 a fresh attempt to cut off the German retreat was made by the IX Corps, which tried to break through the Fondouk Pass and reach the sea ahead of the Germans. After an infantry attack failed to open a clear passage for the tanks, an armoured dash succeeded in penetrating the German lines, but at a heavy cost and too late to intercept the German retreat up the coast. Within days the two German armies had joined hands, offering a united defense along the mountain arc around Tunis from Enfidaville (south of Al-Hammāmāt) in the south to Cap Serrat (west of Bizerte) in the west.

The speed and success of the retreat from the Wādī al-ʿAkārīt presented Germany with the opportunity to evacuate its forces from Tunisia to Sicily. At least a fortnight’s pause was inevitable before the Allies could mount a serious offensive against the new German defensive line, and a period of misty weather blanketed the area, providing a screen for any embarkation and transportation activities. The German Supreme Command, however, was compelled to prolong the campaign in Africa rather than withdraw to the southern shores of Europe. Even in Tunisia it tried to hold a 100-mile (160-km) perimeter - a front too extensive for its resources - in the hope of preserving both Tunis and Bizerte. The Allies were thus able to consider alternative objectives for their inevitable offensive.

Before launching an attack, Alexander reorganized his forces. He brought the U.S. II Corps up from the south to the coast, from the right wing to the left wing, facing Bizerte. He also switched the IX Corps northward and inserted it in the centre between the V Corps and the French XIX Corps, which now adjoined the Eighth Army on the Allied right. On April 20, 1943, the offensive was opened by the Eighth Army with an attack on the enemy’s left flank. The coastal corridor became very narrow beyond Enfidaville, and the advance soon slowed down, coming to a halt on April 23. On April 21 the V Corps attacked from the left centre, through the hills leading to Tunis. The following day the IX Corps struck from the right centre near Goubellat, with the aim of achieving an armoured breakthrough. The effort failed to pierce the German defenses, but it strained them severely and further weakened their remaining tank strength. A pause of nearly two weeks followed on most of the front, but in the north the Americans and a corps of French African troops continued to make a gradual penetration, which brought them within 20 miles (32 km) of Bizerte.

Alexander used the break in the action to redeploy his forces once again. Leaving only a screening force in the right centre near Goubellat, he moved the bulk of the IX Corps to the left centre, concentrated it behind the V Corps, and reinforced it with two divisions from the Eighth Army - the 7th Armoured and 4th Indian. An elaborate deception plan was carried out to conceal the moves and to persuade the enemy command that the next attack would come in the south. Arnim had little chance of recognizing the deception or responding to it after the blow fell because of the Allies’ almost total command of the air. The highly concentrated assault of the IX Corps, now under Gen. Brian Horrocks, was launched in the starlit but moonless early hours of May 6, 1943. It was preceded and covered by an intense artillery bombardment from more than 600 guns, on a front less than 2 miles (3.2 km) wide, in the Majardah (Medjerda) valley leading to Tunis. After daylight, aircraft continued the assault with a terrific storm of bombs. The stunned defenders were soon overrun by the infantry of the 4th Indian and 4th British divisions: the overstretched defense was not only thin but had little depth. The tanks of the 6th and 7th Armoured divisions then drove through the breach, but they lost time in dealing with various small pockets of German resistance. By nightfall they had only advanced a few miles and were still some 15 miles (24 km) from Tunis. On the morning of May 7, however, it became clear that the previous day’s attacks had paralyzed the opposing army to such an extent that it could not develop any tactical countermeasures. That afternoon the leading troops of the British armoured divisions swept into Tunis. The 6th Armoured Division then turned south, and the 7th wheeled north to press the advantage. Almost simultaneously, the Americans and the French poured into Bizerte.

Though their resistance had disintegrated on the northern half the front, in the south the Germans might still have been able to withdraw into the Cap Bon peninsula and there make a prolonged stand. That possibility was frustrated by the rapidity with which the 6th Armoured Division cut across the German rear, securing the neck of the peninsula. German morale was shattered. Unchallenged Allied control of the skies, the absence of any significant German reserve force in the theatre, and the fatal disruption of German command and control structures had doomed what remained of Germany’s ambitions in Africa. German troops found themselves fighting with their backs to the sea — a sea dominated by Allied sea and air power. On May 13, 1943, less than a week after the fall of Tunis, Axis forces in Tunisia surrendered, and more than 250,000 prisoners were taken. North Africa would subsequently serve as a base for future Allied operations against Italy itself.

El Guettar القطار Tunisia Map

Morocco المغرب Map

Bibliography:

- Anderson, Charles R. (1993). Tunisia 17 November 1942 to 13 May 1943. U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-12. ISBN 0-16-038106-1. http://www.history.army.mil/brochures/tunisia/tunisia.htm.

- Atkinson, Rick (2002). An Army at Dawn: the War in North Africa, 1942-1943. New York: Henry Holt & Co.. ISBN 0805062882.

- Howe, G. F. (1957). Northwest Africa: Seizing the Initiative in the West. Washington: Department of the Army.

- The Battle History of the 1st Armored Division, "Old Ironsides.". Washington: Combat Forces Press. 1954.

- Kelly, Orr (2002). Meeting the Fox: The Allied Invasion of Africa, from Operation Torch to Kasserine Pass to Victory in Tunisia. New York: Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0471414292.

- King, Michael J. (1985). Rangers: Selected Combat Operations in World War II. US Army Combat Studies Institute, Command and General Staff College.

- Levine, Alan (1999). The War Against Rommel's Supply Lines. Westport, CT.: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0275965211.

- Middleton, Drew (20 March 1943). "US Force at Pass". New York Times.

- Moorhead, Alan (1968). The March to Tunis: The North African War, 1940-1943. New York: Dell Publishing.

- Wickware, F. G. (1944). The American Yearbook. New York: Nelson.

Magazine References: +

- Airfix Magazines (English) - http://www.airfix.com/

- Avions (French) - http://www.aerostories.org/~aerobiblio/rubrique10.html

- FlyPast (English) - http://www.flypast.com/

- Flugzeug Publikations GmbH (German) - http://vdmedien.com/flugzeug-publikations-gmbh-hersteller_verlag-vdm-heinz-nickel-33.html

- Flugzeug Classic (German) - http://www.flugzeugclassic.de/

- Klassiker (German) - http://shop.flugrevue.de/abo/klassiker-der-luftfahrt

- Le Fana de L'Aviation (French) - http://boutique.editions-lariviere.fr/site/abonnement-le-fana-de-l-aviation-626-4-6.html

- Le Fana de L'Aviation (French) - http://www.pdfmagazines.org/tags/Le+Fana+De+L+Aviation/

- Osprey (English) - http://www.ospreypublishing.com/

- Revi Magazines (Czech) - http://www.revi.cz/

Web References: +

- History of RAF Organisation: https://www.britannica.com/event/North-Africa-campaigns/The-Allied-landings-in-North-Africa

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_El_Guettar

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

If you love our website please add a like on facebook

Please donate so we can make this site even better !!