Pacific Theater of Operations PTO B-25 Mitchell photo's gallery

4th Air Depot based at Garbutt Field Townsville was a major repair center in Australia 13th Dec 1943 NA604

4th Air Depot based at Garbutt Field Townsville was a major repair center in Australia 13th Dec 1943 NA600

Photo description: NA604 Hard standing No. 4 taken from edge of 67 degree runway, Garbutt Field, Townsville, Australia. 13 December 1943. (U.S. Air Force Number B80122AC); Hard standing adjacent to 130 degree runway near main repair depot at Garbutt Field, Townsville, Australia. 13 December 1943. (U.S. Air Force Number 80122AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NA604 NAID: 204948741 Local ID: 342-FH-3A29898-B80122AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NA600 NAID: 204948735 Local ID: 342-FH-3A29896-80122AC

4th Air Depot with two Bell P-400s at Garbutt Field Townsville Australia 4th Dec 1942 NA600

Photo description: South End Of Hangar Of Air Force Project No. 1, 4Th Air Depot At An Airfield In Townsville, Australia. 4 December 1942. (U.S. Air Force Number 77837AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204949039 Local ID: 342-FH-3A29890-77837AC

Propellor Maintenance done at Garbutt Field Townsville Australia 19th May 1943 NA655

Photo description: Pvt. Donald H. Fraser of Northfield, Minn., observes for leakage in a hydromatic test to see if the propellers are functioning properly at the 4th Air Depot engine overhaul and repair shop at Garbutt Field, Townsville, Australia. 19 May 1943. (U.S. Air Force Number 79938AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204948816 Local ID: 342-FH-3A29929-79938AC

43-36201 B-25J Mitchell 13AF Jungle Air Force 43BG bomb Sandakan Jap port in Northern Borneo NA094

Photo description: A North American B-25 Billy Mitchell (lower right) of the 13th AAF, 'the jungle air force' banks sharply to the left after dropping a bomb accurately on dock housing at Sandakan, Japanese supply and ship-building center of Northern Borneo. This type of minimum-altitude work by the "Fightin' 13th’s" planes has cost the Japs throughout Borneo, the Celebes and the Molucca Islands.

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204954093 Local ID: 342-FH-3A32072-55936AC

B-25 Mitchell 42BG390BS Portland Rose with tail gunner Edward Mahike at Rabaul 1944 NA307

Photo description: “Lafayette Journal and Courier” on 10 April 1944 provides the story. “Mahlke a gunner on a speedy Billy Mitchell bomber medium bomber of the 13th AAF, was participating in tree top level bombing and strafing attack against and airdrome in the South Pacific when his aircraft was attacked by two Zeros. Attempting to press home a determined sternal attack, one of the Zeros was driven off by a P-38 of the protecting cover, while Sargent Mahlke manning the tail gun, poured 200 rounds of ammunition into the remaining enemy fighter plane and successfully destroyed it. His accurate marksmanship was confirmed by two bombardier-navigators flying in to separate planes in the formation.” Sgt Edward W. Mahike, 390th Bomb Sqdn, 42d Group tail gunner of the Portland nRose stands hy his "plane after returning from a mission at Rabaul# is credited with one Zero which burst into flames as he turned his guns on it. Stirling Is., Solomons. (U.S. Air Force Number 56004AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204985651 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43618-56004AC

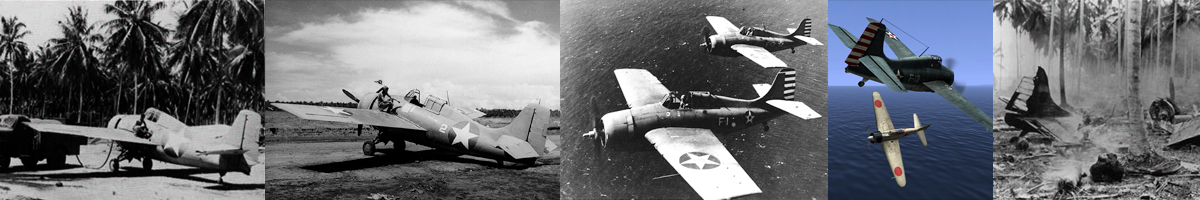

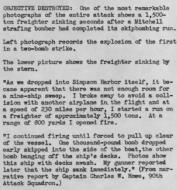

5AF 38BG Sun Setters come in low on a strafing run at Zamboanga Mindanao Philippines 1945 NA318

Photo description: While bombs were still bursting the 5th AF "Sun Setters" come in low on a strafing run at Zamboanga, Mindanao, in the Philippines. Zamboanga was one of the Jap-held ports pounded to prevent their being used for sending troops or supplies to Leyte. (U.S. Air Force Number 58219AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204952481 Local ID: 342-FH-3A31354-58219AC

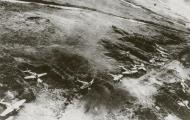

13AF destroy barge fuel hidden along Borneo jungle waterway near Bandjermasin South Kalimantan Indonesia 1945 NA360

Photo description: Netherland East Indies-Hoarded barge fuel, hidden along Borneo jungle waterway near Bandjermasin, is located by 13th AF "snooper." Bomb hits and strafing scattered and fired hundreds of drums. (U.S. Air Force Number 59015AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204954350 Local ID: 342-FH-3A32012-59015AC

Napalm bombing of Brunei Bay Borneo 1945 NA360

Photo description: Napalm Bombing Of Brunei Bay, Borneo. (U.S. Air Force Number 61197AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204954549 Local ID: 342-FH-3A32022-61197AC

B-25 Mitchell 3AF 334BG471BS We'rewolf with crew trained replacement crews Pacific 1944 NA1134

Photo description: round Crew Of 'C' Flight Of The4 71St Bomb Squadron In The Pacific Standing By B-25 'We'Rewolf'. Left To Right, Front: T/Sgt. W.F. Wojick, Georgetown, Ill.; M/Sgt. J.H. Mynhier, Kimmell, Ind.; Sgt. E.E. Crabtree, Wyne, Okla.; Back: Sgt. H.E. Jennejohn (U.S. Air Force Number 122555AC) Constituted as 334th Bombardment Group (Medium) on 9 Jul 1942 and activated on 16 Jul. Assigned to Third AF. Equipped with B-25's. Trained replacement crews for combat. Disbanded on 1 May 1944.

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204989113 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44842-122555AC

TUESDAY, 31 JULY 1945 - SOUTHWEST PACIFIC THEATER OF OPERATIONS (FEAF):

In Japan, 80+ B-24s pound the Kagoshima railroad yards and several other targets in the general area including the Sasebo naval base, Yaki-shima, and Nagasaki; A-26s and B-25s bomb Kanoya and Miyazaki Airfields and nearby targets, the Sasebo naval base, Marushima, warehouses at Nagasaki, and a factory and power plant on Koyagi Island; P-51s attack flak positions at Moji, blast shipping at Iki Island and off the NW and W coast of Kyushu, hit an island WSW of Sasebo, bomb railroad targets and warehouses in the Izumi area, and in general attack the railroad and road net and other communications targets throughout Kyushu and P-61s continue harassing missions during the night. P-51s over the Ryukyu Islands bomb airstrips on Miyako Island, and bomb a town in the Koniya area. On Luzon, B-25s and P-38s support ground action, hitting forces in the Cagayan Valley and Cervantes and Infanta sectors. B-24s pound the area S of Fabrica on Negros Island.

Unit moves: HQ 5AF from Clark Field, Luzon to Okinawa; HQ 6RG from Clark Field, Luzon to Okinawa.Target Japanese Oil Refinery at Koyagi Shima is hit by 5AF B-25 Mitchells 31st July 1945 NA384

Target Japanese Oil Refinery at Koyagi Shima is hit by 5AF B-25 Mitchells 31st July 1945 NA386

Photo description: A North American B-25 Bomber Of The 5Th Af Bomber Command Swoops Over An Oil Refinery On The Coast Of Koyagi Shima Off The Mainland Of Japan. The Mitchells Left The Refinery A Total Wreck. Note This Bomber Still Has Its Bomb Bay Doors Open And Fires Are (U.S. Air Force Number A58279AC) The Jap Oil Refinery At Koyagi Shima Goes Up In Flames As North American B-25 Mitchell Bombers Of The 5Th Af Bomber Command Hit It From Smokestack Level. In One Attack, The Refinery Was Put Out Of Commission. Both Bombs And Strafing Attacks Were Used. (U.S. Air Force Number 58279AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204836434 Local ID: 342-FH-3A03522-A58279AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204836437 Local ID: 342-FH-3A03521-58279ACB-25 Mitchell 13AF 4RG18CMS named Bebe Eyes on Espiritu Santo New Hebrides August 1943 NA005

B-25 Mitchell 13AF 4RG18CMS named Bebe Eyes on Espiritu Santo New Hebrides August 1943 NA007

Photo description: Flying Personnel Of The 18Th Combat Mapping Squadron, Pose Beside The North American B-25 'Bebe Eyes' On Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides. August 1943. [North American F-10]. (U.S. Air Force Number 71117AC) Radio Personnel Of The 18Th Combat Mapping Squadron, Pose Beside The North American B-25 'Bebe Eyes' On Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides. August 1943. [North American F-10] (U.S. Air Force Number 71118AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 205001349 Local ID: 342-FH-3A49235-71117AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 205001352 Local ID: 342-FH-3A49236-71118AC42-87369 B-25D Mitchell at the dispersal area on Stirling Island airstrip Solomons 1944 NA146

Photo description: 42-87369 B-25D Mitchell at the dispersal area on Stirling Island airstrip Solomons 1944 (U.S. Air Force Number 68154AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204985382 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43509-68154AC

13AF B-25 Mitchells after hiting a target in the Bougainville area Solomons 1944 NA1027

Photo description: Rear elements of a 13th AAF Medium bomber formation are shown withdrawing from a Bougainville Island target after having plastered an enemy supply area. Note the objective burning furiously in the background. (U.S. Air Force Number 52908AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204987126 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44148-52908AC

B 25 Mitchell Fat Cat with Capt Garland J Robinson crew and ground crew Southwest Pacific 1943 NA1139

Photo description: "FAT CAT" with those men who make her re-birth possilbe; left to right, front row: S/Sgt. Tony Benson, Minneapolis, Minn.; T/Sgt. John B. Chesson, Lake Charles, La.; T/Sgt. Johnnie H. Leonard, Savannah, Ga.; 1st Lt. Birge A, Neumann, Los Angeles, Calif.; Major John P. Henebry, Plainville, 111.; "Dobo", wire haired terrier, squadron mascot; Capt. Garland J. Robinson, Holeston, Texas. Second row, left to right: Cpl. Wm. D. Rhea, Homer, La.; T/Sgt. Marvin M. Hall, Wetumpka, Ala.; Cpl. James A. Owens, Raleigh, N. C.; Cpl. Virgil L. Bellondi, Methuen, Mass.; S/Sgt. Murray A. Orvin, Statesboro, Ga.; T/Sgt. Charles J. Zuker, Eayton, Ohio. (U.S. Air Force Number 26777AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204989066 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44846-26777AC

American USAAF 13AF 42BG Colonel Harry Wilson CO in B-25 HellBent Guadalcenal Solomon Islands NA343

Photo description: Harry Walters was attached to the 44th FS and scored 3 kills in P-40F #111 which he is standing by he was KIA on Oct 23rd, 1943. His nephew was shot down in Laos and his remains were ID'ed 30 years later and now lie beside Harry's marker at the cemetary in Niles, MI. Colonel (Air Corps) Harry Edgar Wilson, United States Army Air Forces, was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight while serving as Commanding Officer, 42d Bombardment Group (Medium), THIRTEENTH Air Force, during World War II. His devotion to duty and courage under all conditions serve as an inspiration to his fellow flyers. His actions on all these occasions reflect the highest credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of the United States. (U.S. Air Force Number 66920AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204995410 Local ID: 342-FH-3A47185-66920AC

Destroyed Japanese aircraft around Guadalcanal Solomon Islands 1942 NA200

Destroyed Japanese aircraft around Guadalcanal Solomon Islands 1942 NA201

Destroyed Japanese aircraft around Guadalcanal Solomon Islands 1942 NA208

Destroyed Japanese aircraft abandoned on the Munda airstrip New Georgia Solomons 1943 NA1209

Destroyed Japanese aircraft abandoned on the Munda airstrip New Georgia Solomons 1943 NA1211

Destroyed Japanese aircraft abandoned on the Munda airstrip New Georgia Solomons 1943 NA1213

Destroyed Japanese aircraft abandoned on the Munda airstrip New Georgia Solomons 1943 NA1215

Photo description: In its revetment on Munda airfield, New Georgia Island, Solomon Islands lies the skeleton of Jap bomber, its wingtip pointing forlornly to the sky. In contrast, two very live American soldiers chat nonchalantly on the wrecked cockpit. 9 August 1943. (U.S. Air Force Number 79816AC); (U.S. Air Force Number 80203AC); (U.S. Air Force Number 80204AC);(U.S. Air Force Number 56066AC)(U.S. Air Force Number B24865AC); (U.S. Air Force Number 26310AC); (U.S. Air Force Number 23380AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204987132 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44150-79816AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204987135 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44151-80203AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204987129 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44149-56066AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204985470 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43544-B24865AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204985485 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43550-26310AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204985472 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43540-23380AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204987138 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44152-80204ACTwo Japanese Kawanishi H8K Emily and a Kawanishi H6K Mavis Seaplanes at Kure Naval Base Japan 1945 NA415

Photo description: Two Japanese Kawanishi H8K "Emily" (top, center) and a Kawanishi H6K "Mavis" (bottom) flying boats. Jap Seaplanes At Kure Naval Base, Japan. (U.S. Air Force Number 58669AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204836482 Local ID: 342-FH-3A03539-58669AC

Japanese twin engine bomber destroyed on Mindora Island Philippines 1944 NA286

Photo description: This is what a near miss did to a Japanese twin-engine bomber. It's things like this that discourage Nipponese crew chiefs. Mindora Island, Philippine Islands. This is what a near miss did to a Japanese twin-engine bomber. It's things like this that discourage Nipponese crew chiefs. Mindora Island, Philippine Islands. (U.S. Air Force Number 58342AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204952433 Local ID: 342-FH-3A31309-58342AC

IJAAF Mitsubishi Ki-21 Type 97 Heavy Bomber or Sally destroyed at San Manuel Airfield Luzon 1945 NA1099

Photo description: This Jap "Sally," parked on the San Manuel Airfield, was utterly destroyed during a strafing attack on Jap airfields surrounding Manila, capital of the stolen Philippine Empire. (U.S. Air Force Number 68381AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204951401 Local ID: 342-FH-3A30952-68381AC

IJAAF Mitsubishi Ki-57 or Topsy was a Japanese passenger transport aircraft Luzon 1945 NA1317

Photo description: This Jap transport plane "Topsy" was found in spite of the Japanese attempt to hide it. Philippine Islands. (U.S. Air Force Number B60725AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204949710 Local ID: 342-FH-3A30380-B60725AC

IJAAF Mitsubishi Ki-46 Dinah was a twin-engine reconnaissance aircraft Licanan field Mindanao 1945 NA

Photo description: This Japanese light bomber "Dinah" was found in a parking area on the northern dispersal loop of Licanan airdrome, Mindanao, in the Philippine Islands. It was flyable only after major repairs. Note how the Japs had attempted engines from the weather. (U.S. Air Force Number 60724AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204949674 Local ID: 342-FH-3A30375-60724AC

IJAAF Nakajima J1N1 Gekko IRVING night fighter 53-85 captured Pacific area 1945 NA911

Photo description: A few bullet holes can be seen dotting the fuselage of this Jap bomber which waa undergoing repair when captured by our forces. PACIFIC AREA, 1945. (U.S. Air Force Number 63840AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988722 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44721-63840AC

IJAAF Nakajima J1N1 Gekko IRVING night fighter 53-85 captured Pacific area 1945 NA911

Photo description: A few bullet holes can be seen dotting the fuselage of this Jap bomber which waa undergoing repair when captured by our forces. PACIFIC AREA, 1945. (U.S. Air Force Number 63841AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988725 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44722-63841AC

IJAAF Mitsubishi G4M2 Otsu BETTY Navy bomber captured Pacific area 1945 NA933

Photo description:The Mitsubishi G4M was a twin-engine, land-based medium bomber formerly manufactured by the Mitsubishi Aircraft Company, a part of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, and operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy from 1940 to 1945. Its official designation is Mitsubishi Navy Type 1 attack bomber (一式陸上攻撃機, 一式陸攻, Ichishiki rikujō kōgeki ki, Isshikirikukō) and was commonly referred to by Japanese Navy pilots as Hamaki (葉巻, "cigar", lit. "leaf roll") due to the cylindrical shape of its fuselage and its tendency to ignite after a hit. The Allied reporting name was Betty (U.S. Air Force Number 69740AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988755 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44732-69740AC

IJAAF Mitsubishi Type 1 Attack Bomber (G4M) BETTY K762-15 captured Pacific area 1945 NA909

Photo description: A few bullet holes can be seen dotting the fuselage of this Jap bomber which waa undergoing repair when captured by our forces. PACIFIC AREA, 1945. (U.S. Air Force Number 63839AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988719 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44720-63839AC

IJAAF Mitsubishi A6M Zero 221-26D captured Pacific area 1945 NA915

Photo description: A Jap "Hanp" undergoing prop change when taken by allied forces. PACIFIC AREA, 1945.(U.S. Air Force Number 63842AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988728 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44723-63842AC

IJAAF Nakajima Ki-84I Hayate FRANK fighter captured Pacific area 1945 NA917

Photo description: A Jap "Hanp" undergoing prop change when taken by allied forces. PACIFIC AREA, 1945 (U.S. Air Force Number 63843AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988731 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44724-63843AC.

Nakajima Ki-84I Hayate FRANK fighter captured Pacific area 1945 NA925

Photo description: Nakajima Ki-84 Hayate (キ84 疾風, lit. "Gale") is a single-seat fighter flown by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service (U.S. Air Force Number A63851AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988743 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44728-A63851AC

IJAAF Kawasaki Ki-45 Toryu NICK captured Pacific area 1945 NA919

Photo description: The Kawasaki Ki-45 Toryu (屠龍, "Dragonslayer") was a two-seat, twin-engine heavy fighter used by the Imperial Japanese Army in World War II. The army gave it the designation Type 2 Two-Seat Fighter (二式複座戦闘機, Ni-shiki fukuza sentōki); the Allied reporting name was Nick. (U.S. Air Force Number 63844AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988734 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44725-63844AC

IJAAF Kawasaki Ki-45 Toryu NICK captured Pacific area 1945 NA927

Photo description: The Kawasaki Ki-45 Toryu (屠龍, "Dragonslayer") was a two-seat, twin-engine heavy fighter used by the Imperial Japanese Army in World War II. The army gave it the designation "Type 2 Two-Seat Fighter" (二式複座戦闘機, Ni-shiki fukuza sentōki); the Allied reporting name was "Nick". (U.S. Air Force Number 64056AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988746 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44729-64056AC

IJAAF Kawasaki Ki-45-KAI Tei Toryu NICK Army heavy fighter captured Pacific area 1945 NA903

Photo description: The Kawasaki Ki-45 Toryu (屠龍, "Dragonslayer") was a two-seat, twin-engine heavy fighter used by the Imperial Japanese Army in World War II. The army gave it the designation Type 2 Two-Seat Fighter (二式複座戦闘機, Ni-shiki fukuza sentōki); the Allied reporting name was Nick. (U.S. Air Force Number 60644AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988710 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44716-60644AC

IJAAF Kokusai Ku 8II Type 4 Special Transport Glider captured Pacific area 1945 NA921

Photo description: Kokusai Ku-8-II (Kokusai Type 4 Special Transport Glider) was a Japanese military glider used during the Second World War.(U.S. Air Force Number 63850AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988737 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44726-63850AC

IJAAF Aichi D3A2 VAL dive bomber captured Pacific area 1945 NA923

Photo description: Aichi D3A Type 99 Carrier Bomber (Allied reporting name "Val") is a World War II carrier-borne dive bomber. (U.S. Air Force Number 63851AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988740 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44727-63851AC

IJAAF Tachikawa Ki 54 Hei HICKORY captured Pacific area 1945 NA929

Photo description: Tachikawa Ki-54 Hei (Hickory) The Tachikawa Ki-54 was a Japanese twin-engine advanced trainer used during World War II. The aircraft was named Hickory by the Allies. (U.S. Air Force Number 64057AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988749 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44730-64057AC

IJAAF Mitsubishi Ki 46 DINAH twin engine reconnaissance aircraft captured Pacific area 1945 NA931

Photo description:The Mitsubishi Ki-46 was a twin-engine reconnaissance aircraft used by the Imperial Japanese Army in World War II. Its Army Shiki designation was Type 100 Command Reconnaissance Aircraft (一〇〇式司令部偵察機); the Allied brevity code name was "Dinah".(U.S. Air Force Number 64067AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988752 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44731-64067AC

IJAAF Mitsubishi Ki 46 DINAH twin engine reconnaissance aircraft captured Pacific area 1945 NA261

Photo description:The Mitsubishi Ki-46 was a twin-engine reconnaissance aircraft used by the Imperial Japanese Army in World War II. Its Army Shiki designation was Type 100 Command Reconnaissance Aircraft (一〇〇式司令部偵察機); the Allied brevity code name was "Dinah".(U.S. Air Force Number A61181AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204990461 Local ID: 342-FH-3A45371-A61181AC

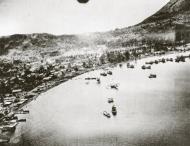

Japanese seaplane tender Nisshin photographed Tonolei Harbor off Bougainville 13th Oct 1942 NA1218

Photo description: Japanese seaplane tender Nisshin photographed Tonolei Harbor off Bougainville 13th Oct 1942 (U.S. Air Force Number 14984AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204987141 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44154-14984AC

Destroyed Japanese Yamazuki Maru 6,998GT Yamashita kisen Guadalcanal Solomon Islands 1942 NA195

Destroyed Japanese Yamazuki Maru 6,998GT Yamashita kisen Guadalcanal Solomon Islands 1942 NA197

Photo description: Japanese Yamazuki Maru(山月丸), 6,998GT, Yamashita kisen(山下汽船).(U.S. Air Force Number B23380AC)(U.S. Air Force Number A23380AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204985465 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43542-B23380AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204985462 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43541-A23380ACDestroyed Japanese Kyushu Maru 8,666GT Harada kisen Guadalcanal Solomon Islands 1942 NA204

Photo description: Japanese Kyushu Maru(九州丸), 8,666GT, Harada kisen(原田汽船).(U.S. Air Force Number A25801AC) (U.S. Air Force Number B25801AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204985477 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43546-A25801AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204985479 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43547-B25801ACDestroyed Japanese Yamaura Maru 6,798GT Yamashita kisen Guadalcanal Solomon Islands 1942 NA203

Photo description: Japanese Yamaura Maru(山浦丸), 6,798GT, Yamashita kisen(山下汽船).(U.S. Air Force Number 25801AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204985475 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43545-25801AC

Destroyed Japanese destroyer Okinami (Yugumo-class) sunk Task Force 38 Manila Luzon Philippines 13th Nov 1944 NA192

Photo description: Japanese destroyer Okinami (Yūgumo-class) lies wrecked in Manila Bay. Okinami was sunk by U.S. carrier aircraft from Task Force 38 on November 13, 1944. One direct hit and several near misses caused the destroyer to sink upright in shallow water. Casualties were 14 men killed and 19 wounded. Manila Harbor, Asashio Kagero class destroyer sunk as a result of American Air Force bombardment. Interpretation by PID, V Bomber Command). February 1945. (U.S. Air Force Number 63865AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204952295 Local ID: 342-FH-3A31261-63865AC

Destroyed Japanese light cruiser Kiso (Kuma-class) sunk Task Force 38 Manila Luzon Philippines 13th Nov 1944 NA320

Photo description: Japanese light cruiser Kiso (Kuma-class). Sunk in Manila Bay on November 13, 1944, by U.S. carrier aircraft from Task Force 38. Kiso was hit by three bombs and sunk in shallow water near Cavite. Casualties were 89 men killed and 105 wounded. Manila Harbor, Kuma-Natero class light cruiser sunk as a resultl of bombardment by the American Air Forces. (Interpretatino by PID, V Bomber Command). February 1945. (U.S. Air Force Number A63865AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204952484 Local ID: 342-FH-3A31262-A63865AC

Destroyed Japanese Freighters sunk Task Force 38 Manila Luzon Philippines 13th Nov 1944 NA190

Photo description: Japanese Manila Harbor. A 5000 g.t. (gross tonnage) sunken Japanese Freighter in foreground; in center, a 4500 g.t. sunken Japanese freighter transport and in the background a 5300 g.t. sunken Japanese freighter. February 1945. (U.S. Air Force Number 63867AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204952292 Local ID: 342-FH-3A31265-63867AC

Destroyed Japanese Freighter Transport 7100GT Nagara Maru class sunk Manila Luzon 13th Nov 1944 NA186

Photo description: Japanese Manila Harbor. A modern 7100 (gross Tonnage) freighter transport, Nagara Maru class. February 1945. (U.S. Air Force Number 63866AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204952286 Local ID: 342-FH-3A31263-63866AC

Destroyed Japanese Freighters and Transport ships sunk Manila Luzon 13th Nov 1944 NA176

Destroyed Japanese Freighters and Transport ships sunk Manila Luzon 13th Nov 1944 NA178

Photo description: Japanese Manila HarborManila Outer Harbor Looking Se Across The South Harbor. In The Foreground Is A 6600 G.T. (Gross Tonnage) Japanese Freighters Nearest Thereto. February 1945. (U.S. Air Force Number 63860AC) Manila South Harbor, Engineer Island and the Inner Basin looking SSW. The inner basin is formed by a protective levee which may be seen extending from the lower left--to the right of the photograph are sunken enemy ships. February 1945. (U.S. Air Force Number 63859AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204952605 Local ID: 342-FH-3A31257-63860AC

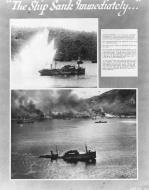

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204952277 Local ID: 342-FH-3A31256-63859ACIJN Japanese Corvette zig zagged frantically off Rabaul but was sunk by 5AF B-25s 1944 NA266

IJN Japanese Corvette zig zagged frantically off Rabaul but was sunk by 5AF B-25s 1944 NA268

IJN Japanese ships sunk off Rabaul by 5AF B-25s Mitchells 1944 NA274

Photo description: When planes of a formation of Mitchell B-25 medium bombers attacked a Japanese corvette in the Southwest Pacific, one of the U. S. aircraft took pictures that tell their own story. This Jap corvette zig-zagged frantically in an effort to escape the bomb pattern being laid by planes of a group of B-25 Mitchell bombers from the U.S. Army 5th Air Force off the New Britain Coast near Rabaul. The planes may be seen over the horizon, at left and center of photo. (U.S. Air Force Number 26734AC) (U.S. Air Force Number A26734AC) (U.S. Air Force Number 55180AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NA266 NAID: 204990464 Local ID: 342-FH-3A45364-26734AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NA268 NAID: 204990467 Local ID: 342-FH-3A45365-A26734AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NA274 NAID: 204990476 Local ID: 342-FH-3A45368-55180ACIJN Japanese Tansport Meisho Maru 4 500GT sunk by 5 Catalinas 15 Miles E of Dyaul Islands 16th Jan 1944 NA265

IJN Japanese Auxiliary Transport Shunko Maru sunk by 5 Catalinas 15 Miles E of Dyaul Islands 16th Jan 1944 NA265

IJN Japanese Freighter-Transports 4-500GT by 5 Catalinas 15 Miles East of Dyaul Islands 16th Jan 1944 NA265

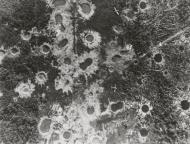

Photo description: These Are The Results Of The Bombing Of 2 Freighter-Transports (4-500 Gross Tons) By 5 Catalinas, 15 Miles East Of Dyaul Islands On 16 Jan 44. The Photographs Were Taken Some 8 Hours Later By A Consolidated B-24. The Smaller Of The Ships (upper) is emitting columns of black smoke and apparently was carrying fuel in drums. Japanese Imperial Army Auxiliary Transport Shunko Maru, sunk with 20 crewmen and 30 passengers KIA. Japanese Imperial Navy transport Meisho Maru, sunk with 12 crewmen KIA. These Japanese transports were part of convoy O-905, en route to Rabaul from Truk. The convoy was made up of transports Shunko Maru, Hozugawa Maru, Meisho Maru and Kosei Maru, guarded by subchasers CH-24 and CH-39. When the convoy was east of New Hanover island, around 0230 hrs, the transports were attacked by Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats. Shunko Maru, Hozugawa Maru and Meisho Maru were heavily damaged and later sank. (U.S. Air Force Number 124128AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204990484 Local ID: 342-FH-3A45363-124128AC

IJAAF Japanese Mitsubishi A6M3 Zero tested at Eagle Farm Brisbane Australia 20th July 1943 NA529

Photo description: On 20 July 1943 Australian pilot Bill Farrior test flew a Japanese Mitsubishi A6M3 Zero or Hamp fighter for 30 minutes. With the aid of an interpreter and a captured Japanese pilot, they were able to determine a suitable cockpit check list. Air Technical Intelligence Unit (ATIU) at Eagle Farm airfield, Brisbane, Australia. Captured and reconditioned Jap Hamp flown by American pilot. AUSTRALIA. (U.S. Air Force Number 55688AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204948657 Local ID: 342-FH-3A29858-55688AC

Wrecks of various US aircraft piled up for salvage at Eagle Farm Brisbane Australia 4th Mar 1943 NA

Photo description: Wrecks of various types of aircraft are piled up for salvage at Eagle Farm, Brisbane, Australia. 4 March 1943. (U.S. Air Force Number 80724AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204948989 Local ID: 342-FH-3A30003-80724AC

War damage in Jones Bridge near Escolta Manila Luzon Philippine 1945 NA218

Photo description: This is a view of the Escolta, or main shopping street, the location of fine shops and theatres in Manila, Philippine Islands. The wrecked Jones Bridge in the foreground has been bridged by U.S. engineers using the Bailey type of span. Plaza (U.S. Air Force Number 83435AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204952334 Local ID: 342-FH-3A31279-83435AC

War damage famed Walled City of Intramurros Manila Philippines 1945 NA220

Photo description: This is the famed Walled City of Intramurros, Manila, Philippine Islands, in which the Japanese holed up for a last stand. Every building within the walls was completely wrecked when U.S. forces shelled the installation for days after the Japanese refused to surrender. The wall was built in the 15th Century and was 40 feet thick in some places, but holes which our artillery smashed through can be seen. The Pasig River and business district of Manila is in the background, and directly in front of the wall is the golf course which was formerly the moat which circled and protected the Walled City.(U.S. Air Force Number 83436AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204952337 Local ID: 342-FH-3A31280-83436AC

War damage famed Legislature Building Japanese headquarters in Manila Philippines 1945 NA208

Photo description: This is the front of the Legislature Building which was Japanese headquarters in Manila, Philippine Islands. After the Japanese signified their intention of fighting to the last, it was decided to pound the building to bits. (U.S. Air Force Number 81169AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204952319 Local ID: 342-FH-3A31274-81169AC

B-25 Mitchell being loaded with One hundred-pound demolition bombs Pacific 1943 NA885

B-25 Mitchell being loaded with One hundred-pound demolition bombs Pacific 1943 NA886

Photo description: One hundred-pound demolition bombs are turned over to the ground crew (U.S. Air Force Number B52395AC); (U.S. Air Force Number C52395AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988676 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44700-B52395AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204988678 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44701-C52395AC43-3486 B-25D Mitchell 7AF at Ewajalein Marshall Islands 5th July 1944 NA289

Photo description: Two Lockheed F-5A's, a North American B-25 Mitchell and a Consolidated B-24 "Liberator" at an airfield on Kwajalein, Marshall Islands July 1944 (U.S. Air Force Number 63786AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204979433 Local ID: 342-FH-3A41420-63786AC

B-25 Mitchell 41BG47BS landing at O'Hara field Apamama Island Gilbert Islands Jan 1944 NA1168

Photo description: A North American B-25 Mitchell of the 47th Bomb Sqdn., 41st Bomb Group, lands at the O'Hara Field, Apamama Island, Gilbert Islands. 20 January 1944. (U.S. Air Force Number 62964AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204984353 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43113-62964AC

B-25 Mitchell 41BG47BS landing at O'Hara field Apamama Island Gilbert Islands Jan 1944 NA1168

Photo description: Crash landing of North American B-25. (U.S. Air Force Number 23254AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204956728 Local ID: 342-FH-3A33027-23254AC

42-649xx B-25G Mitchell raid on Cape Gloucester New Briatin during the landings 12th Jan 1944 NA

Photo description: North American B-25 Mitchell bombers of the 13th AAF are pictured here winging their way over the Rataval supply area, New Britain, after having dropped their bombs on this target for the day. A large fire can be seen on the shore of Talili Bay (U.S. Air Force Number 54813AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204953392 Local ID: 342-FH-3A31684-54813AC

44-29657 B-25J Mitchell 13AF 42BG100BS 1Lt Thomas Cockrell at Puerto Princesa Palawan Philippines 1945 Eduard 0A-0B

Image description: Activated on January 15,1940, 42nd BG patrolled the west coast during 1942 and moved to the Pacific theater in March and April 1943. The Group named "Crusaders" was assigned to 13th AF and entered combat in June 1943, operating from bases in the Solomon Islands. In March 1945 the group moved to the Philippines and attacked shipping along the China coast, targets in French Indochina and bombed airfields and installations in the Philippines. They also supported ground operations on Mindanao and supported Australian forces on Borneo during May and June 1945. Early in 1945 fifth unit, 100th BS, previously known as 106th Reconnaisance Squadron, was incorporated into the Crusaders. This Mitchell was assigned to Lt. Thomas Cockrell, whose son Gordon later followed father's footsteps as he served with US Army as a helicopter pilot. The colors of the noseart are not known, we tend to believe the blue colors of Crusaders' shield and of the insignia were used. Red central circle is also possible, but the red circles were something unwanted on the aircraft fighting against Japanese...

Image Source: https://www.eduard.com/eduard/posters/b-25j-mitchell.html

44-29590 B-25J Mitchell 5AF 71RG17RS My Buck Capt Link Piazzo at Lingayen Philippines 1945 Eduard 0A-0B

Image description: The ship named My Buck belonged to the 17th RS (Reconnaissance Squadron) which was nicknamed “Reckoners”. It was a heavy reconnaissance squadron of the 71st Reconnaissance Group which was activated on March 2, 1942, and conducted anti-submarine patrols on the US West Coast until September of that year. From April 2, 1943, the group was in process of rearming to B-25s and moved to New Guinea in January 1944. Although it was a reconnaissance squadron, the pilots also routinely conducted bombing and attack missions in support of ground troops. Even during long-range reconnaissance flights, their Mitchells were fully armed so they could attack ground targets they found enroute. The unit moved to the Philippines in November 1944 and flew reconnaissance missions over Luzon from there. On April 27, 1946, the unit was deactivated. The My Buck ship looks quite new for numerous mission symbols painted on the fuselage. Also, the border of the Olive Drab and Neutral Grey colors is unusually shaped. It is possible, therefore, that she received a new paint job at the unit for some reason.

Image Source: https://www.eduard.com/eduard/plastic-kits/limited-edition/aircraft/1-72/gunn%c2%b4s-bunny-1-72.html

44-30589 B-25J Mitchell 13AF 42BG100BS 1Lt Don McKenzie at Puerto Princesa Palawan Philippines Mar 1945 Eduard 0A-0B

Image description: The name of this ship from the 100th BS, part of the 42nd BG ‘Crusaders’ composition, refers to the poignant story of one of the best college football players of all time, George ‘Gipper* Gipp, who died at age 25 of streptococcal throat infection and pneumonia. On his deathbed, he told visiting coach Knut Rockne, 'I've got to go, Rock. It's all right. I'm not afraid. Sometime, Rock, when the team is up against it, when things are wrong and the breaks are beating the boys, ask them to go in there with all the/ve got and win just one for the Gipper. I don't know where I'll be then, Rock. But I'll know about it, and I'll be happy A movie was made about the legendary coach in 1940, which includes this scene. The role of George Gipp was portrayed by Ronald Reagan, who years later used the slogan ‘Win one for the Gipper* during his presidential campaign, as the role earned him the nickname Gipper. Crew Chief Sgt. William A. Bean was in charge of the aircraft honored with the slogan.

Image Source: https://www.eduard.com/eduard/plastic-kits/limited-edition/aircraft/1-72/gunn%c2%b4s-bunny-1-72.html

3rd Air Commando Group

Constituted as 3rd Air Commando Group on 25 Apr 1944. Activated on 1 May 1944. Moved to the Philippines late in 1944. Assigned to Fifth AF for operations with P-51, C-47, and L-5 aircraft. Attacked Japanese airfields and installations in the Philippines, supported ground forces on Luzon, provided escort for missions to Formosa and the China coast, made raids on airfields and railways on Formosa, and furnished cover for convoys. Also transported personnel, dropped supplies to ground troops and guerrilla forces, evacuated casualties from front-line strips, adjusted artillery fire, and flew courier and mail routes. Moved to the Ryukyus in Aug 1945. Flew some patrols over Japan, made local liaison flights, and hauled cargo from the Philippines to Okinawa. Moved to Japan in Oct 1945. Inactivated on 25 Mar 1946. Disbanded on 8 Oct 1948.

Squadrons. 3rd Fighter: 1944-1946. 4th Fighter: 1944-1946. 157th Liaison: 1944-1946. 159th Liaison: 1944-1946. 160th Liaison: 1944-1946. 318th Troop Carrier: 1944-1946.

Stations. Drew Field, Fla, 1 May 1944; Lakeland AAFld, Fla, 5 May 1944; Alachua AAFld, Fla, 20 Aug 1944; Drew Field, Fla, 6-24 Oct 1944; Leyte, Dec 1944; Mangaldan, Luzon, c. 26 Jan 1945; Laoag, Luzon, Apr 1945; Ie Shima, Aug 1945; Chitose, Japan, c. 27 Oct 1945-25 Mar 1946.

Commanders. Maj Klem F Kalberer, May 1944; Col Arvid E Olson Jr, Jun 1944; Lt Col Walker M Mahurin, Sep 1945; Lt Col Charles H Terhune, 20 Oct 1945-unkn.

Campaigns. Air Offensive, Japan; China Defensive; Western Pacific; Leyte; Luzon; China Offensive.

Decorations. Philippine Presidential Unit Citation.

Insigne. None.

35th Fighter Group

35th Fighter Group

Constituted as 35th Pursuit Group (Interceptor) on 22 Dec 1939. Activated on 1 Feb 1940. Trained with P-35, P-36, P-39, and P-40 aircraft. Two squadrons (21st and 34th) moved to the Philippines in Nov 1941. Headquarters and another squadron (70th) sailed for Manila on 5 Dec but because of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor they returned to the US where the squadron flew some patrols. Headquarters and the 70th squadron sailed for Australia on 12 Jan 1942. Three days later all the combat squadrons were relieved and three others, still in the US, were assigned. Headquarters reached Australia in Feb 1942 and moved on to India. Meanwhile the squadrons had moved from the US to Australia and were training for combat with P-39's. Headquarters was transferred back to Australia, without personnel and equipment, in May 1942.

Redesignated 35th Fighter Group. Served in combat with Fifth AF, operating successively from bases in Australia, New Guinea, Owi, Morotai, and the Philippines. First used P-38's and P-39's; equipped with P-47's late in 1943 and with P-51's in Mar 1945. Helped to halt the Japanese advance in Papua and took part in the Allied offensive that recovered the rest of New Guinea, flying protective patrols over Port Moresby, escorting bombers and transports, attacking Japanese airfields and supply lines, and providing cover for Allied landings. In 1944 began long-range missions against enemy airfields and installations in the southern Philippines, Halmahera, and Borneo, preparatory to the US invasion of the Philippines. Beginning in Jan 1945, operated in support of ground forces on Luzon. Also escorted bombers and completed some fighter sweeps to Formosa and China. Bombed and strafed railways and airfields in Kyushu and Korea after moving to Okinawa in Jun 1945. Moved to Japan in Oct 1945 and, as part of Far East Air Forces, trained, took part in maneuvers, and flew surveillance patrols over Honshu. Redesignated 35th Fighter-Interceptor Group in Jan 1950. Equipped with F-80's.

Entered combat in the Korean War in Jul 1950 and almost immediately began converting from F-80's to F-51's. Operated from bases in Japan and Korea in support of UN ground forces, bombing and strafing enemy supply lines, troop concentrations, and communications. Transferred without personnel and equipment to Japan in May 1951. Remanned and equipped with F-51's and F-80's. Provided air defense for Japan. Converted to F-86 aircraft in 1955.

Squadrons. 18th: 1940. 20th: 1940. 21st: 1940-1942. 34th: 1940-1942. 39th: 1942-. 40th: 1942-. 41st: 1942-. 70th: 1941-1942.

Stations. Moffett Field, Calif, 1 Feb 1940; Hamilton Field, Calif, 10 Sep 1940-5 Dec 1941 and 9 Dec 1941-12 Jan 1942; Brisbane, Australia, 1 Feb 1942; New Delhi, India, Mar 1942; Sydney, Australia, 4 May 1942; Port Moresby, New Guinea, 22 Jul 1942; Tsili Tsili, New Guinea, 15 Aug 1943; Nadzab, New Guinea, 5 Oct 1943; Gusap, New Guinea, 7 Feb 1944; Owi, Schouten Islands, 22 Jul 1944; More tai, 27 Sep 1944; Mangaldan, Luzon, c. 20 Jan 1945; Lingayen, Luzon, c. 10 Apr 1945; Clark Field, Luzon, 19 Apr 1945; Okinawa, 28 Jun 1945; Irumagawa, Japan, Oct 1945; Yokota, Japan, 16 Mar 1950; Ashiya, Japan, 8 Jul 1950; Pohang, Korea, 14 Jul 1950; Tsuiki, Japan, 13 Aug 1950; Pohang, Korea, 3 Oct 1950; Yonpo, Korea, 18 Nov 1950; Pusan, Korea, c. 3 Dec 1950; Johnson AB, Japan, 25 May 1951; Yokota, Japan, 14 Aug 1954-.

Commanders. Maj O R Strickland, 1940; Col George P Tourtellot, 1940-unkn; Col Richard A Legg, 12 Mar 1942; Lt Col Malcolm A Moore, 26 Jul 1943; Lt Col Edwin A Doss, 23 Oct 1943; Lt Col Furlo S Wagner, 12 Feb 1944; Col Edwin A Doss, 4 May 1944; Col Harney Estes Jr, 27 Jul 1945; Col Raymond P Todd, 22 Mar 1946; Lt Col Richard D Dick, c. 13 Sep 1946; Col James R Gunn Jr, c. 11 Feb 1947; Col Ford Lauer, 28 Apr 1947; Col Ray W Clifton, 1 Sep 1947; Col Edgar M Scattergood Jr, 21 Jun 1948; Lt Col Bert W Marshall Jr, Aug 1948; Lt Col Archie M Burke, 13 May 1949; Lt Col Jack D Dale Jr, Nov 1949; Col William P McBride, 22 Feb 1951; Lt Col Homer M Cox, May 1951; Col John C Habecker, 25 Jun 1951; Col John R Propst, 6 Jun 1952; Lt Col Albert S Aiken, Feb 1955; Col Maurice L Martin, Jun 1955; Col Raymond M Gehrig, Aug 1955-.

Campaigns. World War II: East Indies; Air Offensive, Japan; China Defensive; Papua; New Guinea; Bismarck Archipelago; Western Pacific; Leyte; Luzon; Ryukyus; China Offensive. Korean War: UN Defensive; UN Offensive; CCF Intervention; 1st UN Counteroffensive; CCF Spring Offensive.

Decorations. Distinguished Unit Citation: Papua, 23 Jul 1942-23 Jan 1943. Philippine Presidential Unit Citation. Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation: 7 Sep 1950-7 Feb 1951.

Insigne Shield: Azure, a dexter cubit arm or grasping a dagger point to base gules. Motto: Attack To Defend (Approved 21 Feb 1941.)

348th Fighter Group

348th Fighter Group

Constituted as 348th Fighter Group on 24 Sep 1942 and activated on 30 Sep. Prepared for combat with P-47's. Moved to the Southwest Pacific, May-Jun 1943, and assigned to Fifth AF. Operated from New Guinea and Noemfoor until Nov 1944. Flew patrol and reconnaissance missions and escorted bombers to targets in New Guinea and New Britain. Col Neel E Kearby was awarded the Medal of Honor for action over New Guinea on 11 Oct 1943: after leading a flight of four fighters to reconnoiter the enemy base at Wewak, Col Kearby sighted a Japanese bomber formation escorted by more than 30 fighters; despite the heavy odds and a low fuel supply, and although his mission had been accomplished, Kearby ordered an attack, personally destroying six of the enemy planes. For covering Allied landings and supporting ground forces on New Britain, 16-31 Dec 1943, the group was awarded a DUC. In 1944 began to attack airfields, installations, and shipping in western New Guinea, Ceram, and Halmahera to aid in neutralizing those areas preparatory to the US invasion of the Philippines. After moving to the Philippines in Nov 1944, provided cover for convoys, flew patrols, escorted bombers, attacked enemy airfields, and supported ground forces. Received a DUC for withstanding assaults by enemy fighters to cover bombers raiding Clark Field on 24 Dec 1944. Also attacked shipping along the China coast and escorted bombers to Formosa and the Asiatic mainland. Moved to the Ryukyus in Jul 1945 and completed some escort and attack missions to Kyushu before the war ended. Moved to Japan in Oct 1945 as part of Far East Air Forces. Inactivated on 10 May 1946.

Redesignated 108th Fighter Group. Allotted to ANG (NJ) on 24 May 1946. Extended federal recognition on 16 Oct 1946. Called to active duty on 1 Mar 1951. Redesignated 108th Fighter-Bomber Group. Assigned first to Strategic Air Command and later to Tactical Air Command. Equipped with F-47's. Relieved from active service on 1 Dec 1952 and returned to the control of ANG (NJ).

460th Fighter Squadron

Squadrons. 149th: 1951-1952. 153d 1951-1952. 340th: 1942-1946. 341st (later 141st): 1942-1946; 1951-1952. 342d: 1942-1946. 460th: 1944-1946.

Stations. Mitchel Field, NY, 30 Sep 1942; Bradley Field, Conn, 4 Oct 1942; Westover Field, Mass, 29 Oct 1942; Providence, RI, c. 3 Jan 1943; Westover Field, Mass, 28 Apr-9 May 1943; Port Moresby, New Guinea, 23 Jun 1943; Finschhafen, New Guinea, 16 Dec 1943; Saidor, New Guinea, 29 Mar 1944; Wakde, 22 May 1944; Noemfoor, 26 Aug 1944; Leyte, 16 Nov 1944; San Marcelino, Luzon, 4 Feb 1945; Floridablanca, Luzon, 15 May 1945; Ie Shima, 9 Jul 1945; Itami, Japan, Oct 1945-10 May 1946. Newark Mun Aprt, NJ, 1 Mar 1951; Turner AFB, Ga, 14 Mar 1951; Godman AFB, Ky, 9 Dec 1951-1 Dec 1952.

Commanders. Col Neel E Kearby, Oct 1942; Col Robert R Rowland, 17 Nov 1943; Lt Col William M Banks, 8 Jun 1945; Maj Walter G Benz, 26 Nov 1945-unkn. Maj J D Zink, Mar 1951; Col Alvan C Gillem II, Jun 1951; Col Carl W Stapleton, c. Nov 1951; Col Donald J Strait, 14 Jan 1952; Col George Laven Jr, 4 Aug-1 Dec 1952.

Campaigns. Air Offensive, Japan; China Defensive; New Guinea; Bismarck Archipelago; Western Pacific; Leyte; Luzon; China Offensive.

Decorations. Distinguished Unit Citations: New Britain, 16-31 Dec 1943; Philippine Islands, 24 Dec 1944. Philippine Presidential Unit Citation

Insigne Shield: Azure, within a bordure dimidiated, gules, hand gauntleted in armour proper, encircled with wreath of laurel, vert, grasping a torch argent, flamant proper. Motto: Per Caelum Victoriae - Through the Skies to Victory. (Approved 15 Aug 1951.)

Pacific Theater Operations - 5AF

The Fifth Air Force (5 AF) is a numbered air force of the United States Air Force Pacific Air Forces (PACAF). It is headquartered at Yokota Air Base, Japan. It is the U.S. Air Force's oldest continuously serving Numbered Air Force. The organization has provided 80 years of continuous air power to the Pacific since its establishment in September 1941.

Fifth Air Force is the Headquarters Pacific Air Forces forward element in Japan, and maximizes partnership capabilities and promotes bilateral defense cooperation. In addition, 5 AF is the air component to United States Forces Japan.

Its mission is three-fold. First, it plans, conducts, controls, and coordinates air operations assigned by the PACAF Commander. Fifth Air Force maintains a level of readiness necessary for successful completion of directed military operations. And last, but certainly not least, Fifth Air Force assists in the mutual defense of Japan and enhances regional stability by planning, exercising, and executing joint air operations in partnership with Japan. To achieve this mission, Fifth Air Force maintains its deterrent force posture to protect both U.S. and Japanese interests, and conducts appropriate air operations should deterrence fail.

History

Fourteen Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses that survived the Battle of the Philippines left Mindanao for Darwin, Australia, between 17 and 20 December 1941, the only aircraft of the Far East Air Force to escape. After its evacuation from the Philippines on 24 December 1941, FEAF headquarters moved to Australia and was reorganized and redesignated 5 Air Force on 5 February 1942, with most of its combat aircraft based on fields on Java. It seemed at the time that the Japanese were advancing just about everywhere. The remaining heavy bombers of the 19th Bombardment Group, based at Malang on Java, flew missions against the Japanese in an attempt to stop their advance. They were joined in January and February, two or three at a time, by 37 B-17Es and 12 LB-30s of the 7th Bombardment Group. The small force of bombers, never numbering more than 20 operational at any time, could do little to prevent the invasion of the Netherlands East Indies, launching valiant but futile attacks against the masses of Japanese shipping, with six lost in combat, six in accidents, and 26 destroyed on the ground.

The 7th Bombardment Group was withdrawn to India in March 1942, leaving the 19th to carry on as the only B-17 Fortress-equipped group in the South Pacific. About this time it was decided that replacement B-17s would not be sent to the southwest Pacific, but be sent exclusively to the Eighth Air Force which was building up in England. By May, Fifth Air Force's surviving personnel and aircraft were detached to other commands and the headquarters remained unmanned for several months, but elements played a small part in the Battle of the Coral Sea (7–8 May 1942) when the 435th Bomb Squadron of the 19th Bomb Group saw the Japanese fleet gathering in Rabaul area nearly two weeks before the battle actually took place. Because of the reconnaissance activity of the 435th Bomb Squadron, the US Navy was prepared to cope adequately with the situation. The squadron was commended by the US Navy for its valuable assistance not only for its excellent reconnaissance work but for the part played in the battle.

Headquarters Fifth Air Force was re-staffed at Brisbane, Australia on 18 September 1942 and placed under the command of Major General George Kenney. United States Army Air Forces units in Australia, including Fifth Air Force, were eventually reinforced and re-organised following their initial defeats in the Philippines and the East Indies. At the time that Kenney had arrived, Fifth Air Force was equipped with three fighter groups and five bombardment groups.

Fighter Groups:

8th FG (P-39) Townsville, Australia

35th FG (P-40) Port Moresby, New Guinea

49th FG (P-40) Darwin, Australia

Bomber Groups:

3rd BG (B-25, A-20, & A-24) Charters Towers, Australia

19th BG (Non-Operational. Battle scarred from Philippines & Java) Mareeba, Australia

22nd BG (B-26) Woodstock, Australia

38th BG (B-25) Charters Towers, Australia

43rd BG (B-17 until 1943; B-24 1943–1945) Port Moresby, New Guinea

In addition, Fifth Air Force controlled two transport squadrons and one photographic squadron comprising 1,602 officers and 18,116 men.

Kenney was later appointed commander of Allied air forces in the South West Pacific Area, reporting directly to General Douglas MacArthur. Under Kenney's leadership, the Fifth Air Force and Royal Australian Air Force provided the aerial spearhead for MacArthur's island hopping campaign.

US Far East Air Forces

On 4 November 1942, the Fifth Air Force commenced sustained action against the Japanese in Papua New Guinea and was a key component of the New Guinea campaign (1942–1945). Fifth Air Force engaged the Japanese again in the Philippines campaign (1944–45) as well as in the Battle of Okinawa (1945).

Fifth Air Force along with Thirteenth Air Force in the Central Pacific and Seventh Air Force in Hawaii were assigned to the newly created United States Far East Air Forces (FEAF) on 3 August 1944. FEAF was subordinate to the U.S. Army Forces Far East and served as the headquarters of Allied Air Forces Southwest Pacific Area. By 1945, the three numbered air forces were supporting operations throughout the Pacific. FEAF was the functional equivalent in the Pacific of the United States Strategic Air Forces (USSTAF) in the European Theater of Operations.

Order of battle, 1945

5AF Order of battle, 1945V Fighter Command Night Fighter Units V Bomber Command Photo Reconnaissance 54th Troop Carrier Wing 3d ACG (P-51, C-47) 418th NFS 3d BG (L) (B-25, A-20) 6th RG (F-5, F-7) 2d CCG 8th FG (P-40, P-38) 421st NFS 22d BG (M/H) (B-26 – B-24) 71st RG (B-25) 317th TCG 35th FG (P-47, P-51) 547th NFS 38th BG (M) (B-25) 374th TCG (1943 only) 49th FG (P-40, P-47, P-38) 43d BG (H) (B-24) 375th TCG 58th FG (P-47) 90th BG (H) (B-24) 433d TCG 348th FG (P-47, P-51) 312th BG (L) (A-20) 475th FG (P-38) 345th BG (M) (B-25) 380th BG (H) (B-24) 417th BG (L) (A-20) LEGEND: ACG – Air Commando Group, FG – Fighter Group, NFS – Night Fighter Squadron, BG (L) – Light Bomb Group, BG (M) – Medium Bomb Group, BG (H) – Heavy Bomb Group, RG – Reconnaissance Group, CCG – Combat Cargo Group, TCG – Troop Carrier Group

When the war ended, Fifth Air Force had an unmatched record of 3,445 aerial victories, led by the nation's two top fighter aces Major Richard Bong and Major Thomas McGuire, with 40 and 38 confirmed victories respectively, and two of Fifth Air Force's ten Medal of Honor recipients.

Shortly after World War II ended in August, Fifth Air Force relocated to Irumagawa Air Base, Japan, about 25 September 1945 as part of the Allied occupation forces. The command remained in Japan until 1 December 1950 performing occupation duties.

Korean War

In 1950, Fifth Air Force was called upon again, becoming the main United Nations Command combat air command during the Korean War, and assisted in bringing about the Korean Armistice Agreement that formally ended the war in 1953.

In the early morning hours of 25 June, North Korea launched a sudden, all-out attack against the south. Reacting quickly to the invasion, Fifth Air Force units provided air cover over the skies of Seoul. The command transferred to Seoul on 1 December 1950, remaining in South Korea until 1 September 1954.

In this first Jet War, units assigned to the Fifth Air Force racked up an unprecedented 14.5 to 1 victory ratio. By the time the truce was signed in 1953, Fifth Air Force had flown over 625,000 missions, downing 953 North Korean and Chinese aircraft, while close air support accounted for 47 percent of all enemy troop casualties.

Thirty-eight fighter pilots were identified as aces, including Lieutenant Colonel James Jabara, America's first jet ace; and Captain Joseph McConnell, the leading Korean War ace with 16 confirmed victories. Additionally, four Medals of Honor were awarded to Fifth Air Force members. One other pilot of note was Marine Major John Glenn, who flew for Fifth Air Force as part of an exchange program.

With the end of combat in Korea, Fifth Air Force returned to normal peacetime readiness Japan in 1954.

Cold War

Not only concerned with maintaining a strong tactical posture for the defense of both Japan and South Korea, Fifth Air Force played a critical role in helping the establishment of the Japan Air Self-Defense Force as well as the Republic of Korea Air Force. These and other peacetime efforts lasted a decade before war clouds once again developed in the Pacific.

This time, the area of concern was Southeast Asia, beginning in 1964 with the Gulf of Tonkin Crisis. Fifth Air Force furnished aircraft, aircrews, Support personnel, and supplies throughout the eight years of combat operations in South Vietnam and Laos. Since 1972, the Pacific has seen relative calm, but that doesn't mean Fifth Air Force hasn't been active in other roles. The command has played active or supporting roles in a variety of issues ranging from being first on the scene at the Korean Air Lines Flight 007 shoot down in 1983 to deploying personnel and supplies for the Persian Gulf War in 1990.

During this time span, the size of Fifth Air Force changed as well. With the activation of Seventh Air Force in 1986, fifth left the Korean Peninsula and focused its energy on continuing the growing bilateral relationship with Japan.

The Fifth Air Force's efforts also go beyond combat operations. Fifth Air force has reacted to natural disasters in Japan and abroad. These efforts include the Great Hanshin earthquake in 1995 and Super Typhoon Paka which hit Guam in 1997. Fifth Air Force has reached out to provide assistance to victims of floods, typhoons, volcanoes, and earthquakes throughout the region.

The 432d Tactical Fighter Wing flew F-16s from Misawa Air Base from July 1, 1984 – October 31, 1994. On the inactivation of the wing, its personnel, aircraft, and other assets were used to reform the 35th Fighter Wing.

Present Day

Today, according to the organization's website, major components include the 18th Wing, Kadena Air Base, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan; the 35th Fighter Wing at Misawa Air Base, and the 374th Airlift Wing at Yokota Air Base. Kadena AB hosts the 18th Wing, the largest combat wing in the USAF. The Wing includes F-15 fighters, KC-135 refuelers, E-3 Airborne Warning and Control System aircraft, and HH-60G Pave Hawk rescue helicopters, and represents a major combat presence and capability in the Western Pacific. The 35th Fighter Wing, Misawa Air Base, Japan, includes two squadrons equipped with the most modern Block 50 F-16 variant, dedicated to the suppression of enemy air defenses. The final formation is the 374th Airlift Wing, at Yokota Air Base, Japan.

According to a 2017 study by two US Navy commanders, in case of a surprise Chinese ballistic missile attack against airbases in Japan, more than 200 U.S. aircraft would be trapped or destroyed on the ground in the first hours of the conflict.

Lineage, assignments, stations, and components

Lineage

Established as Philippine Department Air Force on 16 August 1941

Activated on 20 September 1941

Redesignated: Far East Air Force on 16 November 1941

Redesignated: 5 Air Force on 5 February 1942

Redesignated: Fifth Air Force* on 18 September 1942.

Fifth Air Force is not to be confused with a second "Fifth" air force created as a temporary establishment to handle combat operations after the outbreak of hostilities on 25 June 1950, in Korea. This numbered air force was established as Fifth Air Force, Advance, and organized at Itazuki AB, Japan, assigned to Fifth Air Force, on 14 July 1950. It moved to Taegu AB, South Korea, on 24 July 1950, and was redesignated Fifth Air Force in Korea at the same time. After moving, it apparently received command control from U.S. Far East Air Forces. The establishment operated from Pusan, Taegu, and Seoul before being discontinued on 1 December 1950.

Commands

V Air Force Service: 18 June 1943 – 15 June 1944

V Air Service Area: 9 January 1944 – 15 June 1944

5 Bomber (later, V Bomber): 14 November 1941 – 31 May 1946

V Fighter: 25 August 1942 – 31 May 1946

5 Interceptor: 4 November 1941 – 6 April 1942

Became Army Air Force Infantry unit during Battle of the Philippines (1941–42) (20 December 1941 – 9 April 1942)

Far East Air Service (later, 5 Air Force Base; V Air Force Base): 28 October 1941 – 2 November 1942

Divisions

39th Air Division: 1 September 1954 – 15 January 1968

41st Air Division: 1 September 1954 – 15 January 1968

43d Air Division: 1 September 1954 – 1 October 1957

313th Air Division: 1 March 1955 – 1 October 1991

314th Air Division: 31 May 1946 – 1 March 1950; 1 December 1950 – 18 May 1951; 15 March 1955 – 8 September 1986

315 Air Division (formerly, 315 Composite Wing): 1 June 1946 – 1 March 1950.

Wings

8th Fighter Wing, later 8th Tactical Fighter Wing, 1950s

18th Wing: 1 Oct 1991-.

35th Fighter Wing: 1 Oct 1994-.

51st Fighter Wing: 1955-September 1986

374th Airlift Wing: 1 Apr 1992-.

432d Tactical Fighter Wing, Misawa Air Base, Japan: July 1, 1984 – May 31, 1991; 432d Fighter Wing from June 1, 1991 - October 31, 1994 (wing personnel and assets thereafter used to reactivate 35th Fighter Wing)

6100th Support Wing, Tachikawa Air Base, Japan: "Brigadier General Thomas R. FORD Replaced Col. Lewis B. MENG as commander of 6100th Support Wing effective" 11 June 1962. "6100 Support Wing was Major Air Command control (MAJCON) unit directly subordinate to Headquarters (HQ) 5 Air Force. Contains.. functions of various subordinate elements of 6100 Support Wing (Kanto Base Command)."

Groups

2nd Combat Cargo Group: October 1944-15 January 1946

Assignments

Philippine Department, U.S. Army, 20 September 1941

US Forces in Australia (USFIA), 23 December 1941

Redesignated: US Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA), 5 January 1942

American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM), 23 February 1942

Allied Air Force, Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA), 2 November 1942

Far East Air Forces (Provisional), 15 June 1944

Far East Air Forces, 3 August 1944

Redesignated: Pacific Air Command, United States Army, 6 December 1945

Redesignated: Far East Air Forces, 1 January 1947

Redesignated Pacific Air Forces, 1 July 1957—present

Stations

Nichols Field, Luzon, 20 September 1941

RAAF Base Darwin, Australia, 31 December 1941

Bandoeng, Java, 18 January 1942

Brisbane AAB, Australia,c 1 March 1942

Nadzab Airfield, New Guinea, 15 June 1944

Owi Airfield, Schouten Islands, Netherlands East Indies, 10 August 1944

Bayug Airfield, Leyte, Philippines, c. 20 November 1944

McGuire Field, Mindoro, Philippines, January 1945

Clark Field, Luzon, Philippines, April 1945

Hamasaki (Motobu Airfield), Okinawa, 4 August 1945

Irumagawa AB, Japan, c. 25 September 1945

Tokyo, Japan, 13 January 1946

Nagoya, Japan, 20 May 1946

Seoul AB (K-16), Korea, 1 December 1950

Taegu AB (K-2), Korea, 22 December 1950

Seoul AB (K-16), 15 June 1951

Osan AB, Korea, 25 January 1954

Nagoya AB (later, Nagoya AS; Moriyama AS), Japan, 1 September 1954

Fuchu AS, Japan, 1 July 1957

Yokota AB, Japan, 11 November 1974–present

5th Air Force (5th AF) "Forgotten Fifth" U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF)

The 5th Air Force (5th AF) was part of the U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF). On February 5, 1942 the prewar Far East Air Force (FEAF) was redesignated the 5th Air Force (5th AF) in Australia. Also known as the Fifth Air Force (Fifth AF) or V Air Force (V AF). Unofficially dubbed the "Forgotten Fifth" as forgotten in the South West Pacific Area (SWPA) at the end of the supply chain.

On September 3, 1942 the 5th Air Force (5th AF) was assigned to Major General George C. Kenney becomes Commanding Officer (C.O.) with its Headquarters in Brisbane and retains command of the Allied Air Forces in the Southwest Pacific. On October 15, 1942 promoted to the rank of Lieutenant General and was the the highest ranking officer under General Douglas MacArthur.

As the leader of the 5th Air Force, Kenney fought an innovative and creative war against the Japanese using available aircraft and weapons effectively. Officers under his command created strafer variants of aircraft adding forward firing extra machine guns to the nose of A-20 Havocs and B-25 Mitchells. The 5th Air Force used ordnance including the daisy cutter (wire wrapped bombs) and parachute-retarded fragmentation bomb (parafrag bomb) that were suited for destroying parked aircraft and inflicting damage in jungle areas. Officers under his command pioneered "skip bombing" flying bombers at low level to skip bombs off the surface of the sea to hit an enemy ship instead of ineffective high altitude bombing runs that allowed the target to maneuver away once bombs were released.

On June 15, 1944 the Far East Air Force (FEAF) was reformed and combined the 5th Air Force (5th AF) in the South West Pacific Area (SWPA) and 13th Air Force (13th AF) in the South Pacific (SOPAC) under the command of General George C. Kenney. The FEAF continues until the end of the Pacific War.

Fighter Group (FG)

8th Fighter Group (8th FG) "Cyclone's Flying Circus"

35th Fighter Group (35th FG)

49th Fighter Group (49th FG)

58th Fighter Group (58th FG)

347th Fighter Group (347th FG)

348th Fighter Group (348th FG)

475th Fighter Group (475th FG) "Satan's Angels"Bombardment Group (BG)

3rd Bombardment Group (3rd BG) "The Grim Reapers"

19th Bombardment Group (19th BG)

22nd Bombardment Group (22nd BG) "Red Raiders"

38th Bombardment Group (38th BG) "Sun Setters"

43rd Bombardment Group (43rd BG) "Ken's Men"

90th Bombardment Group (90th BG) "Jolly Rogers"

312th Bombardment Group (312th BG) "Roarin' 20's"

345th Bombardment Group (345th BG) "Air Apaches"

380th Bombardment Group (380th BG) "Flying Circus"

417th Bombardment Group (417th BG) "Sky Lancers"hotographic Reconnaissance Group (PRG)

6th Photographic Reconnaissance Group (6th PRG)

Tactical Reconnaissance Group (PRG)

71st Tactical Reconnaissance Group (71st TRG)

Night Fighter Squadron (NFS)

418th Night Fighter Squadron (418th NFS)

421st Night Fighter Squadron (421st NFS)Troop Carrier Wing (TCW)

54th Troop Carrier Wing (54th TCW)

Troop Carrier Group (TCG)

63rd Troop Carrier Group (63rd TCG)

317th Troop Carrier Group (317th TCG)

374th Troop Carrier Group (374th TCG)

375th Troop Carrier Group (375th TCG)

433rd Troop Carrier Group (433rd TCG)Service Group (SG)

Far East Air Force - Combat Replacement Training Center (FEAF-CRTC, 360th Service Group, 8th Service Group)

Commanding Officers (C.O.)

Lt. General George C. Kenney

source: https://pacificwrecks.com/units/usaaf/5af/index.html

Thirteenth Air Force

Formed on December 14, 1942. Operated primarily in South Pacific Area (SPA) of the Pacific Theater of Operations (PTO)

5th Bombardment Group

Unit formed in 1915. Large number of B-18s and B-17C/Ds destroyed during Pearl Harbor Attack. Surviving B-17s sent to New Hebrides in 1942. Re-equipped in Hawaii with B-24s and redeployed in August 1943. Stationed in Solomon Islands, Admiralty Islands, Netherlands East Indies, Schouten Islands, Molucca Islands, Philippines. Transitioned to RB-29s in 1946.

23d Bombardment Squadron

31st Bombardment Squadron

72d Bombardment Squadron

394th Bombardment Squadron

42nd Bombardment Group (42nd BG) "The Crusaders"

Background: The 42nd Bombardment Group (42nd BG) was part of the U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF). Includes Headquarters Squadron (HQ), 69th Bombardment Squadron (69th BS), 70th Bombardment Squadron (70th BS), 75th Bombardment Squadron (75th BS) and 390th Bombardment Squadron (390th BS). Nicknamed "The Crusaders". On December 14, 1942 became part of the 13th Air Force (13th AF).

Headquarters Squadron (HQ)

On April 22, 1943 the 42nd Bombardment Group, Headquarters Squadron arrives on Fiji. On June 6, 1943 transfers to Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. On October 22, 1943 moves to Renard Field in the Russell Islands. On January 20, 1944 transfers to Stirling Airfield in the Treasury Islands.

69th Bombardment Squadron (69th BS)

The 69th Bombardment Squadron originally part of the 38th Bombardment Group (38th BG), 5th Air Force.

70th Bombardment Squadron (70th BS)

The 70th Bombardment Squadron (Medium) originally part of the 38th Bombardment Group (38th BG), 5th Air Force.

75th Bombardment Squadron (75th BS)

The 70th Bombardment Squadron (Medium) operated in the South Pacific (SoPAC).

106th Reconnaissance Squadron (106th RS)

During January 1944 attached to the 42nd Bombardment Group (42nd BG) on May 9, 1944 redesignated 100th Bombardment Squadron.

100th Bombardment Squadron (100th BS)

On May 9, 1944 the 106th Reconnaissance Squadron (106th RS) was redesignated as the 100th Bombardment Squadron (100th BS).

390th Bombardment Squadron (390th BS)

The 390th Bombardment Squadron (390th BS).

307th Bombardment Group

Established with B-17s in April 1942; transitioned to B-24s at Hickam Field, November 1942. Stationed in Solomon Islands, Admiralty Islands, Netherlands East Indies, Philippines. Transitioned to B-29s in 1946

370th Bombardment Squadron

371st Bombardment Squadron

372d Bombardment Squadron

424th Bombardment Squadron

4th Reconnaissance Group

Constituted as 4th Photographic Group on 14 Jul 1942 and activated on 23 Jul. Trained for overseas duty with F-4's. Moved to the South Pacific late in 1942. Assigned to Thirteenth AF in Jan 1943. Redesignated 4th Photographic Reconnaissance and Mapping Group in May 1943, 4th Photographic Group (Reconnaissance) in Nov 1943, and 4th Reconnaissance Group in May 1945. From Dec 1942 to May 1945 the group, based successively on New Caledonia, Espiritu Santo, Guadalcanal, and Morotai, flew reconnaissance missions over enemy territory to supply air force units with target and damage assessment photographs and to provide army and navy units with intelligence on Japanese troop concentrations, installations, shore defenses, supply routes, and shipping. It also produced maps of Allied and enemy-held territory and prepared navigation charts for US units. During the last three months of the war the group photographed Japanese positions and installations on Mindanao and Borneo to aid US and Australian operations. Moved to Leyte in Sep 1945. Inactivated on 15 Jan 1946. Disbanded on 6 Mar 1947.

17th Combat Mapping Squadron

18th Combat Mapping Squadron

19th Combat Mapping Squadron

20th Combat Mapping Squadron

38th Combat Mapping Squadron

Squadrons. 17th: 1942-1946. 18th: 1942-1944. 19th: 1942-1943. 20th: 1942-1943. 38th: 1945-1946.

Stations. Colorado Springs, Colo, 23 Jul-24 Oct 1942; New Caledonia, 22 Nov 1942; Espiritu Santo, 22 Jan 1943; Guadalcanal, 6 May 1944; Morotai, 12 Dec 1944; Leyte, Sep 1945-15 Jan 1946.

Commanders. 2nd Lt Everett E Shaw, 23 Jul 1942; Lt Col Francis L Rivard, 10 Aug 1942; Lt Col Charles P Hollstein, 3 Sep 1942; Col Paul C Schauer, 18 Jul 1943; Lt Col Hillford R Wallace, 7 Jun 1944; Maj Sidney L Hardin, 4 Aug 1944; Lt Col Hershell E Parsons, 20 Jan 1945-unkn.

Campaigns. Guadalcanal; New Guinea; Northern Solomons; Bismarck Archipelago; Western Pacific; Leyte; Southern Philippines.

Decorations. Philippine Presidential Unit Citation.

Insigne Shield: Azure, three piles and three like ordinaries transposed conjoined in honor point or. (Approved 28 Nov 1942.)

868th Bombardment Squadron

Established in July 1943 with SB-24 RADAR aircraft; assigned directly to 13th AF Headquarters. Flew low level, anti-shipping strikes under the cover of darkness. Also flew as pathfinders for high-altitude bombers. Special missions were flown against land targets at night and one of the intentions was to prevent the Japanese from sleeping. Stationed in Solomon Islands, Admiralty Islands, Schouten Islands, Netherlands East Indies, Philippines, Okinawa. Inactivated December 1945

The Thirteenth Air Force

HENDERSON FIELD had been won in the violent air, sea,and land battles which had occurred in the hectic days of October and November. There would be more fighting on Guadalcanal, more battles at sea in the Slot, many more in the air, too, but henceforth there would be far less doubt as to the outcome. In October and November there had been little margin for error or miscalculation. The race had been far too close for comfort. But now from November forward, the Allied potential began to show under the energetic leadership of Admiral Halsey; men, ships, guns, and planes reached Guadalcanal in numbers sufficient to provide a modest margin of safety.

When the smoke had cleared away and the pressure had eased somewhat, the men who sent the planes on their missions took stock of their weapons. By the end of November, General Harmon's heavy bombers had been in operation four full months. They had gone out from Espiritu Santo almost daily, staging through Guadalcanal as often as possible, and now their commanders and aircrews had gathered sufficient operational data to permit an assessment of their achievements and an analysis of the employment of heavy bombardment aviation in the theater. Of 610 of all types of Japanese planes contacted, B-17 gunners had claimed twenty-one aircraft destroyed and fifty-seven damaged. On the debit side, twenty-one bombers had been lost while executing their missions, but more than half this number could be attributed to operational losses. No more than six could be recorded as combat losses, excluding the three additional planes which were badly damaged by naval gunfire while parked on Henderson Field. Altogether these aircraft had carried down with them a total of 101 officers and men of the 5th and 11th Groups, of which number a third could be charged to operational causes rather than to combat with the enemy.

Pilots, crews, and commanders had learned many lessons during the first sixteen weeks of continuous operations. There was complete confidence in the B-17 as a combat weapon; antiaircraft fire repeatedly had hurt the bombers, and so had the 7.7-mm. machine guns and 20-mm. cannon of the Japanese Zeros, but the toughness of the B-17 had enabled most of the planes to return to their bases. They were highly durable and pilots respected them. That this toughness would be needed was evident from a marked improvement in enemy fighter tactics since the initial contacts in July and August. Zero pilots always fought more aggressively over their own bases, and it was believed that fresh pilots with considerable experience were reaching the Solomons from other fronts.

Certainly, the B-17 crews were having trouble in meeting effectively the frontal attack so often employed by the Zero pilots. To combat this menace General Harmon had requested, as early as 31 August, modification of all 11th Group B-17's after the pattern completed on one of his heavy bombers by the Cheyenne Modification Center. This operation involved the installation of two .50-cal. nose guns and another in the radio compartment, together with new mounts for the waist guns and larger waist ammunition boxes to provide flexible feed. Initial experience with these improvements had shown a material contribution to the defense of the B-17 against frontal attack, but the field of fire still remained badly restricted and it was doubted that anything short of a nose turret would solve the problem.

Colonel Saunders in his own analysis cited the toughness and aggressiveness of the fighter unit encountered over Buin, where enemy fighters seemed much more difficult to shoot down, indicating the presence of armor in the planes. He granted the need for a nose power turret and for installation of armor plate in the entire nose compartment.

Had his B-17's been so equipped, several bombardiers and navigators would not have been killed, but beyond this, his observations of operations and enemy tactics in the South Pacific indicated that the time had come for a radical change in the design of heavy bombers. The B-17, he felt, had been developed to the extreme limit, and now a completely new aircraft should be built.

Nevertheless, only two aircraft were known to have been lost to enemy fighters, one on 24 September over Buin and the other on 18 November after a running fight of seventy miles. Thus far, and in most cases, formations of three or more B-17's had proved sufficiently strong to prevent serious damage at the hands of enemy fighters.

If the record of the heavy bombers against enemy aircraft was outstanding, the statistics turned in by Saunders' aircrews indicated quite a different performance against enemy ships. Since 31 July a total of 1,163 surface craft of all types had been contacted, of which 60 were attacked with a total of 828 bombs. Of this number, the pilots claimed 4 sunk and 15 damaged, exclusive of 9 others believed damaged as a result of close misses.

General Harmon had presented to Admiral Halsey on 22 October a statistical analysis of the effect of search activities upon the striking power of the B-17's, concluding that on a basis of eight planes flying daily search missions, each of eleven hours' duration, approximately 78 per cent of the group's total effort was devoted to reconnaissance work. The remaining 22 per cent of flying time was available for strike missions. Harmon conceded that this view of the problem was somewhat academic, but nevertheless he believed it emphasized the necessity for preserving the offensive effort of the bombers. He accordingly had recommended that no more than 25 per cent of the heavy bomber effort should be expended thereafter on reconnaissance, that a careful survey be made of all equipment and its employment in order to secure a reduction of the current figure, and that Hudsons be placed in service to supplement the search effort of the PBY's and B-17's. As for targets, he recommended that the heavy bombers be concentrated upon important objectives lying beyond the range of other types of aircraft, or in force upon vital surface objectives at all ranges. But the planes should not be assigned definite strike missions against small detachments of cruisers and destroyers at long range because of the improbability of obtaining hits on such highly maneuverable targets, except by employment of more planes than the target was worth.