Mixed photo's of Messerschmitt Bf-109G Gustav

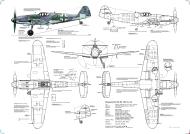

- Artwork Messerschmitt Line drawing Bf 109 G-10 Large Blue print 01

- Artwork Messerschmitt Line drawing Bf 109 G-10 Large Blue print by Heli Schmidt 0A

- Artwork Messerschmitt Line drawing Bf 109 G-14 Large Blue print 01

- Artwork Messerschmitt Line drawing Bf 109 G-2 Large Blue print 01

- Artwork Messerschmitt Line drawing Bf 109 G-2 Large Blue print 02

- Artwork Messerschmitt Line drawing Bf 109G3 Large Blue print 01

- Artwork Messerschmitt Line drawing Bf 109 G-6 Large Blue print 01

- Avia S-199 Czechoslovak AF IF01 with SC250 by Helmut Schmidt 0A

- Avia S-199 IF 01 WNr S199185 Czechoslovakia 0A

- Bf 109 G-14AS/R3 Erla 1./JGr.Ost White 41 Gerd Hauter Rosenborn Germany Nov 1944 Plewka 2005 P32

- Bf 109 G-14AS/R3 Erla 1./JGrOst White 41 Gerd Hauter Rosenborn Germany Nov 1944 Plewka 2005 P33A

- Bf 109 G-14AS/R3 Erla 1./JGrOst White 41 Gerd Hauter Rosenborn Germany Nov 1944 Plewka 2005 P33B

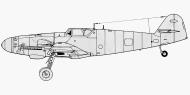

- Blue print by Otterkins Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-10 Erla line drawing for 3D models 0A

- Blue print by Otterkins Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 line drawing for 3D models 0A

- Gun footage showing a Bf 109G being sd by RAF 266Sqn Typhoon over France IWM C4140A

- Gun footage showing a Luftwaffe pilot abandoning his machine during aerial combat ebay1

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-10 abandoned at Pocking Germany wars end 1945 ebay1

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-10 Erla Black 11 WNr 770184 abandoned Rrien Germany 1945 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-10 Erla White 67 WNr 770293 or 770093 after escaping to Sweden 14th Apr 1945 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-10/R3 Erla lies abandoned as a US soldier takes a close look 1945 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-10/U4 chevron Black 3 awaits scrapping 1945 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-10/U4 Erla WNr 151591 unknown unit 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14 12./JG76 Yellow 11 Plivot near Athis Sep 1944 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14AS Erla III./JG76 White 14 WNr 780xxx Stade Saxony Aug 1944 ebay 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14AS Erla unknown unit Kurt Gruning Germany 1944 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14AS Erla White 4 WNr 786316 Kassel Germany Jun 1945 ebay 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14AS Erla White 4 WNr 786316 Kassel Germany Jun 1945 ebay 02

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14AS Erla White 4 WNr 786316 Kassel Germany Jun 1945 ebay 03

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14AS Erla White 4 WNr 786316 Kassel Germany Jun 1945 ebay 04

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14AS Erla White 4 WNr 786316 Kassel Germany Jun 1945 ebay 05

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14AS Erla White 4 WNr 786316 Kassel Germany Jun 1945 ebay 06

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14AS Erla White 4 WNr 786316 Kassel Germany Jun 1945 ebay 07

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14 Erla being towed towards the runway area Germany 1945 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14 Erla front profile shot 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14 Erla White 2 sits abandoned Zellhausen 1945 ebay1

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14 Erla Yellow 12 with USAAF 36FG personnel Kassel Roth West May 1945 ebay1

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14 Erla Yellow 12 with USAAF 36FG personnel Kassel Roth West May 1945 ebay2

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14 Erla Yellow 12 with USAAF 36FG personnel Kassel Roth West May 1945 ebay3

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14 III./JG76 Blue 11 WNr 460520 Plivot near Athis Sep 1944 ebay1

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14 JGx Black 16 abandoned at Zellhausen summer 1945 ebay1

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14 JGx Black 16 abandoned at Zellhausen summer 1945 ebay2

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-14 White 11 Kastrup May 1945 ebay 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-2 5./JGx Black 1 bar landing accident unknown unit and location Russia 1942 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-2 5./JGx Black 1 bar unknown unit lie abandoned in Russia 1942 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-2 JGx White 6 unknown unit and location ebay1

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-2/R6 staffel line up unknown location 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-2/R6 undergoing routine field maintenance 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-2/Trop 6 Staffel unknown unit Yellow 16 La Marsa 1943 ebay 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-4/R3 unknown unit aerial photo showing twin fuel tank configuration partial Stkz Wx+xx 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-5 9./JGxx Yellow 1 unknown unit and pilot 1944 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-5 Erla Maschinenwerk GmbH Leipzig March 1943 ebay 1

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-5 White 3 after a landing mishap and unknown Goofy looking pilot 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 aerial photo 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 Black 10 unknown unit balancing on its nose after a landing mishap 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 Black 9 unknown unit undergoing a engine repair 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 engine run up 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 Erla undergoing a propellor change 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 force landed behind allied lines ebay1

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 JGx White 7 sites abandoned summer 1945 ebay1

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6/R2 destroyed reconnaissance version USAF 546th AAA unit 1945 ebay 1

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6/R3 on approach to land giving a nice frontal view perspective 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6/R3/Trop unknow unit line up 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6/R6 aerial photo showing the R6 pods 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 Stab aircraft parked in its bomb shelter gives a nice frontal view perspective 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 Stkz xx+xE abandoned at Munchen Oberwiesenfeld 1945 ebay1

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 Stkz xx+xE abandoned at Munchen Oberwiesenfeld 1945 ebay2

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 Stkz xx+xE abandoned at Munchen Oberwiesenfeld 1945 ebay3

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6/Trop unknown unit 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 unknow III Gruppe unit taxing 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 unknown unit and pilot catch a nap while waiting for the go signal 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 unknow unit Black 3 under going maintenance 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 used for camouflage testing 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 White 1 being prepared for another mission showing RLM 74 and 75 camouflage 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6 White 36 unknown unit 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109G8 WNr xxx100 unit and location unknown Eastern Prussia winter 1944 45 ebay1

- Messerschmitt Bf 109G abandoned airframe 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109G abandoned airframe remanence 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109G abandoned airframe remanence 02

- Messerschmitt Bf 109G abandoned and captured by soviet forces wars end 1945 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109G and Fw 190 abandoned at Pocking Germany wars end 1945 ebay1

- Messerschmitt Bf 109G being refueled showing late war camouflage Germany 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109G undergoing firing tests 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109G unknown unit force landed 01

- Messerschmitt Bf 109G Yellow 3 lies abandoned after a landing mishap wars end 1945 ebay1

- Messerschmitt Bf 109G Yellow 3 lies abandoned after a landing mishap wars end 1945 ebay2

- MTO Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-2 White 8 abandoned airframe North Africa 01

- MTO Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6/Trop Black 6 sun bathing 01

- MTO Messerschmitt Bf 109G abandoned Martuba Libya November 1942 01

- MTO Messerschmitt Bf 109G unknown unit (Y6+I) abandoned airframe El Aouiana Tunis Tunesien May 1943 01

- MTO Messerschmitt Bf 109G Yellow 2 abandoned in Castel Benito Lybia ebay1

- MTO Messerschmitt Bf 109G Yellow 2 abandoned in Castel Benito Lybia ebay2

- MTO Messerschmitt Bf 109G Yellow 2 abandoned in Castel Benito Lybia ebay3

- P Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-4 Erla flown by Karl Hannes during high altitude testing Deurne Belgium Mar 1943 01

- P Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-4 Erla flown by Karl Hannes during high altitude testing Deurne Belgium Mar 1943 02

- P Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-4 Erla flown by Karl Hannes during high altitude testing Deurne Belgium Mar 1943 03

- P Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-4 Erla flown by Karl Hannes during high altitude testing Deurne Belgium Mar 1943 04

- P Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-4 Erla flown by Karl Hannes during high altitude testing Deurne Belgium Mar 1943 05

- P Messerschmitt Bf 109V31 Stkz SG+EK WNr 5642 by Helmut Schmidt 0A

- P Messerschmitt Bf 109V31 Stkz SG+EK WNr 5642 ebay 1

- P Messerschmitt Bf 109V31 Stkz SG+EK WNr 5642 ebay 2

Specifications The Messerschmitt Bf 109K4 aircraft profiles

Specifications The Messerschmitt Bf 109G Gustav

Data from The Great Book of Fighters[79] and the Finnish Air Force Bf 109 Manual

General characteristics

Crew: 1

Length: 8.95 m (29 ft 4 in)

Wingspan: 9.925 m (32 ft 7 in)

Height: 2.6 m (8 ft 6 in)

Wing area: 16.05 m2 (172.8 sq ft)

Airfoil: NACA 2R1 14.2; tip: NACA 2R1 11.35[80]

Empty weight: 2,247 kg (4,954 lb)

Gross weight: 3,148 kg (6,940 lb)

Max takeoff weight: 3,400 kg (7,496 lb)

Powerplant: 1 × Daimler-Benz DB 605A-1 V-12inverted liquid-cooled piston engine 1,475 PS (1,455 hp; 1,085 kW)

Propellers: 3-bladed VDM 9-12087, 3 m (9 ft 10 in) diameter light-alloy constant-speed propellerPerformance

Maximum speed: 520 km/h (323 mph; 281 kn) at sea level

588 km/h (365 mph; 317 kn) at 4,000 m (13,123 ft)

640 km/h (400 mph; 350 kn) at 6,300 m (20,669 ft)

616 km/h (383 mph; 333 kn) at 8,000 m (26,247 ft)

Cruise speed: 590 km/h (367 mph; 319 kn) at 6,000 m (19,685 ft)

Range: 850 km (528 mi; 459 nmi)

Ferry range: 1,000 km (621 mi; 540 nmi) with droptank

Service ceiling: 12,000 m (39,000 ft)

Rate of climb: 17 m/s (3,300 ft/min)

Wing loading: 196 kg/m2 (40 lb/sq ft)

Power/mass: 0.344 kW/kg (0.209 hp/lb)Armament

Guns:

2 × 13 mm (.51 in) synchronized MG 131 machine guns with 300 rpg

1 × 20 mm (.78 in) MG 151/20 cannon as centerline Motorkanone with 200 rpg [81] or

1 x 30 mm (1.18 in) MK 108 cannon as centerline Motorkanone with 65 rpg (G-6/U4 variant)

2 × 20 mm MG 151/20 underwing cannon pods with 135 rpg (optional kit—Rüstsatz VI)

Rockets: 2 × 21 cm (8 in) Wfr. Gr. 21 rockets (G-6 with BR21)

Bombs: 1 × 250 kg (551 lb) bomb or 4 × 50 kg (110 lb) bombs or 1 × 300-litre (79 US gal) drop tankAvionics

FuG 16Z radio

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 in a nutshell

National origin:- Germany Role:- Fighter Manufacturer:- Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (BFW) Messerschmitt AG Designer:- Willy Messerschmitt and Robert Lusser First flight:- 29 May 1935[1] Introduction:- February 1937 Retired:- 9 May 1945, Luftwaffe 27 December 1965, Spanish Air Force Primary users:- Luftwaffe, Hungarian Air Force, Aeronautica Nazionale Repubblicana, Royal Romanian Air Force, Finland Number built:- 33,984[2] +603 Avia S-199 +239 HA-1112 Variants:- Avia S-99/S-199 and Hispano Aviación HA-1112

Messerschmitt Bf 109 Story

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a German World War II fighter aircraft that was the backbone of the Luftwaffe's fighter force.[3] The Bf 109 first saw operational service in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War and was still in service at the dawn of the jet age at the end of World War II in 1945.[3] It was one of the most advanced fighters of the era, including such features as all-metal monocoque construction, a closed canopy, and retractable landing gear. It was powered by a liquid-cooled, inverted-V12 aero engine.[4] From the end of 1941, the Bf 109 was steadily being supplemented by the Focke-Wulf Fw 190. It was commonly called the Me 109, most often by Allied aircrew and among the German aces, even though this was not the official German designation.[5]

It was designed by Willy Messerschmitt and Robert Lusser who worked at Bayerische Flugzeugwerke during the early to mid-1930s.[4] It was conceived as an interceptor, although later models were developed to fulfill multiple tasks, serving as bomber escort, fighter-bomber, day-, night-, all-weather fighter, ground-attack aircraft, and reconnaissance aircraft. It was supplied to several states during World War II, and served with several countries for many years after the war. The Bf 109 is the most produced fighter aircraft in history, with a total of 33,984 airframes produced from 1936 to April 1945.[2][3]

The Bf 109 was flown by the three top-scoring German fighter aces of World War II, who claimed 928 victories among them while flying with Jagdgeschwader 52, mainly on the Eastern Front. The highest-scoring fighter ace of all time was Erich Hartmann, who flew the Bf 109 and was credited with 352 aerial victories. The aircraft was also flown by Hans-Joachim Marseille, the highest-scoring German ace in the North African Campaign who achieved 158 aerial victories. It was also flown by several other aces from Germany's allies, notably Finnish Ilmari Juutilainen, the highest-scoring non-German ace, and pilots from Italy, Romania, Croatia, Bulgaria, and Hungary. Through constant development, the Bf 109 remained competitive with the latest Allied fighter aircraft until the end of the war.[6]

A significant portion of Bf 109 production originated in Nazi concentration camps, including Flossenbürg, Mauthausen-Gusen, and Buchenwald.

Design and development

Origins

During 1933, the Technisches Amt (C-Amt), the technical department of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM) ('Reich Aviation Ministry'), concluded a series of research projects into the future of air combat. The result of the studies was four broad outlines for future aircraft:[7]

Rüstungsflugzeug I for a multi-seat medium bomber

Rüstungsflugzeug II for a tactical bomber

Rüstungsflugzeug III for a single-seat fighter

Rüstungsflugzeug IV for a two-seat heavy fighterRüstungsflugzeug III was intended to be a short range interceptor, replacing the Arado Ar 64 and Heinkel He 51 biplanes then in service. In late March 1933 the RLM published the tactical requirements for a single-seat fighter in the document L.A. 1432/33.[8]

The fighter needed to have a top speed of 400 km/h (250 mph) at 6,000 m (19,690 ft), to be maintained for 20 minutes, while having a total flight duration of 90 minutes. The critical altitude of 6,000 metres was to be reached in no more than 17 minutes, and the fighter was to have an operational ceiling of 10,000 metres.[8] Power was to be provided by the new Junkers Jumo 210 engine of about 522 kW (700 hp). It was to be armed with either a single 20 mm MG C/30 engine-mounted cannon firing through the propeller hub as a Motorkanone, or two synchronized, engine cowl-mounted 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17 machine guns, or one lightweight engine-mounted 20 mm MG FF cannon with two 7.92 mm MG 17s.[9] The MG C/30 was an airborne adaption of the 2 cm FlaK 30 anti-aircraft gun, which fired very powerful 'Long Solothurn' ammunition, but was very heavy and had a low rate of fire. It was also specified that the wing loading should be kept below 100 kg/m2. The performance was to be evaluated based on the fighter's level speed, rate of climb, and maneuverability, in that order.[8]

It has been suggested that Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (BFW) was originally not invited to participate in the competition due to personal animosity between Willy Messerschmitt and RLM director Erhard Milch;[nb 1] however, recent research by Willy Radinger and Walter Shick indicates that this may not have been the case, as all three competing companies—Arado, Heinkel and BFW—received the development contract for the L.A. 1432/33 requirements at the same time in February 1934.[8] A fourth company, Focke-Wulf, received a copy of the development contract only in September 1934.[8] The powerplant was to be the new Junkers Jumo 210, but the proviso was made that it would be interchangeable with the more powerful, but less developed Daimler-Benz DB 600 powerplant.[11] Each was asked to deliver three prototypes for head-to-head testing in late 1934.

Prototypes

Prototype V3

Design work on Messerschmitt Project Number P.1034 began in March 1934, just three weeks after the development contract was awarded. The basic mock-up was completed by May, and a more detailed design mock-up was ready by January 1935. The RLM designated the design as type 'Bf 109,' the next available from a block of numbers assigned to BFW.[8]

The first prototype (Versuchsflugzeug 1 or V1), with civilian registration D-IABI, was completed by May 1935, but the new German engines were not yet ready. To get the 'R III' designs into the air, the RLM acquired four Rolls-Royce Kestrel VI engines by trading Rolls-Royce a Heinkel He 70 Blitz for use as an engine test-bed.[nb 2] Messerschmitt received two of these engines and adapted the engine mounts of V1 to take the V-12 engine upright. V1 made its maiden flight at the end of May 1935 at the airfield located in the southernmost Augsburg neighborhood of Haunstetten, piloted by Hans-Dietrich 'Bubi' Knoetzsch. After four months of flight testing, the aircraft was delivered in September to the Luftwaffe's central test centre at the Erprobungsstelle Rechlin to take part in the design competition.

In 1935, the first Jumo engines became available, so V2 was completed in October using the 449 kW (600 hp) Jumo 210A engine. V3 followed, the first to be mounted with guns, but it did not fly until May 1936 due to a delay in procuring another Jumo 210 engine.

Design competition

After Luftwaffe acceptance trials were completed at their headquarters Erprobungsstelle (E-Stelle) military aviation test and development facility at Rechlin, the prototypes were moved to the subordinate E-Stelle Baltic seacoast facility at Travemünde for the head-to-head portion of the competition. The aircraft participating in the trials were the Arado Ar 80 V3, the Focke-Wulf Fw 159 V3, the Heinkel He 112 V4 and the Bf 109 V2. The He 112 arrived first, in early February 1936, followed by the rest of the prototypes by the end of the month.

Because most fighter pilots of the Luftwaffe were used to biplanes with open cockpits, low wing loading, light g-forces and easy handling like the Heinkel He 51, they were very critical of the Bf 109 at first. However, it soon became one of the frontrunners in the contest, as the Arado and Focke-Wulf entries, which were intended as 'backup' programmes to safeguard against failure of the two favourites, proved to be completely outclassed. The Arado Ar 80, with its gull wing (replaced with a straight, tapered wing on the V3) and fixed, spatted undercarriage was overweight and underpowered, and the design was abandoned after three prototypes had been built. The parasol winged Fw 159, potentially inspired by the same firm's earlier Focke-Wulf Fw 56, was always considered by the E-Stelle Travemünde facility's staff to be a compromise between a biplane and an aerodynamically more efficient, low-wing monoplane. Although it had some advanced features, it used a novel, complex retractable main undercarriage which proved to be unreliable.[12]

Initially, the Bf 109 was regarded with disfavour by E-Stelle test pilots because of its steep ground angle, which resulted in poor forward visibility when taxiing; the sideways-hinged cockpit canopy, which could not be opened in flight; and the automatic leading edge slats on the wings which, it was thought, would inadvertently open during aerobatics, possibly leading to crashes. This was later borne out in combat situations and aerobatic testing by various countries' test establishments. The leading edge slats and ailerons would flutter rapidly in fast tight turns, making targeting and control difficult, and eventually putting the aircraft into a stall condition. They were also concerned about the high wing loading.[13]

The Heinkel He 112, based on a scaled-down Blitz, was the favourite of the Luftwaffe leaders. Compared with the Bf 109, it was also cheaper.[14] Positive aspects of the He 112 included the wide track and robustness of the undercarriage (this opened outwards from mid wing, as opposed to the 109s which opened from the wing root), considerably better visibility from the cockpit, and a lower wing loading that made for easier landings. In addition, the V4 had a single-piece, clear-view, sliding cockpit canopy and a more powerful Jumo 210Da engine with a modified exhaust system. However, the He 112 was also structurally complicated, being 18% heavier than the Bf 109, and it soon became clear that the thick wing, which spanned 12.6 m (41 ft 4 in) with an area of 23.2 m2 (249.7 ft2) on the first prototype (V1), was a disadvantage for a light fighter, decreasing the aircraft's rate of roll and manoeuvrability. As a result, the He 112 V4 which was used for the trials had new wings, spanning 11.5 m (37 ft 8.75 in) with an area of 21.6 m2 (232.5 ft2). However, the improvements had not been fully tested and the He 112 V4 could not be demonstrated in accordance with the rules laid down by the Acceptance Commission, placing it at a distinct disadvantage.

Because of its smaller, lighter airframe, the Bf 109 was 30 km/h (20 mph) faster than the He 112 in level flight, and superior in climbing and diving. The Commission ultimately ruled in favour of the Bf 109 because of the Messerschmitt test pilot's demonstration of the 109's capabilities during a series of spins, dives, flick rolls and tight turns, throughout which the pilot was in complete control of the aircraft.[15]

In March, the RLM received news that the British Supermarine Spitfire had been ordered into production. It was felt that a quick decision was needed to get the winning design into production as soon as possible, so on 12 March, the RLM announced the results of the competition in a document entitled Bf 109 Priority Procurement, which ordered the Bf 109 into production. At the same time, Heinkel was instructed to radically redesign the He 112.[16] The Messerschmitt 109 made its public debut during the 1936 Berlin Olympics, when the V1 prototype was flown.[17]

Design features

As with the earlier Bf 108, the new design was based on Messerschmitt's 'lightweight construction' principle, which aimed to minimise the number of separate parts in the aircraft. Examples of this could be found in the use of two large, complex brackets which were fitted to the firewall. These brackets incorporated the lower engine mounts and landing gear pivot point into one unit. A large forging attached to the firewall housed the main spar pick-up points, and carried most of the wing loads. Contemporary design practice was usually to have these main load-bearing structures mounted on different parts of the airframe, with the loads being distributed through the structure via a series of strong-points. By concentrating the loads in the firewall, the structure of the Bf 109 could be made relatively light and uncomplicated.[18]

An advantage of this design was that the main landing gear, which retracted through an 85-degree angle, was attached to the fuselage, making it possible to completely remove the wings for servicing without additional equipment to support the fuselage. It also allowed simplification of the wing structure, since it did not have to bear the loads imposed during takeoff or landing. The one major drawback of this landing gear arrangement was its narrow wheel track, making the aircraft unstable while on the ground. To increase stability, the legs were splayed outward somewhat, creating another problem in that the loads imposed during takeoff and landing were transferred up through the legs at an angle.[19]

The small rudder of the Bf 109 was relatively ineffective at controlling the strong swing created by the powerful slipstream of the propeller during the early portion of the takeoff roll, and this sideways drift created disproportionate loads on the wheel opposite to the swing. If the forces imposed were large enough, the pivot point broke and the landing gear leg would collapse outward into its bay.[19] Experienced pilots reported that the swing was easy to control, but some of the less-experienced pilots lost fighters on takeoff.[20]

Because of the large ground angle caused by the long legs, forward visibility while on the ground was very poor, a problem exacerbated by the sideways-opening canopy. This meant that pilots had to taxi in a sinuous fashion which also imposed stresses on the splayed undercarriage legs. Ground accidents were a problem with inexperienced pilots, especially during the later stages of the war when pilots received less training before being sent to operational units.[20] At least 10% of all Bf 109s were lost in takeoff and landing accidents, 1,500 of which occurred between 1939 and 1941.[21] The installation of a fixed 'tall' tailwheel on some of the late G-10s and −14s and the K-series helped alleviate the problem to a large extent.[22]

From the inception of the design, priority was given to easy access to the powerplant, fuselage weapons and other systems while the aircraft was operating from forward airfields. To this end, the entire engine cowling was made up of large, easily removable panels which were secured by large toggle latches. A large panel under the wing centre section could be removed to gain access to the L-shaped main fuel tank, which was sited partly under the cockpit floor and partly behind the rear cockpit bulkhead. Other, smaller panels gave easy access to the cooling system and electrical equipment.[19] The engine was held in two large, forged, Elektron magnesium alloy Y-shaped legs, one per side straddling the engine block, which were cantilevered from the firewall. Each of the legs was secured by two quick-release screw fittings on the firewall. All of the main pipe connections were colour-coded and grouped in one place, where possible, and electrical equipment plugged into junction boxes mounted on the firewall. The entire powerplant could be removed or replaced as a unit in a matter of minutes,[19] a potential step to the eventual adoption of the unitized-powerplant Kraftei engine mounting concept used by many German combat aircraft designs, later in the war years.

Another example of the Bf 109's advanced design was the use of a single, I-beam main spar in the wing, positioned more aft than usual (to give enough room for the retracted wheel), thus forming a stiff D-shaped torsion box. Most aircraft of the era used two spars, near the front and rear edges of the wings, but the D-box was much stiffer torsionally, and eliminated the need for the rear spar. The wing profile was the NACA 2R1 14.2 at the root and NACA 2R1 11.35 at the tip,[23] with a thickness to chord ratio of 14.2% at the root and 11.35% at the tip.

Another major difference from competing designs was the higher wing-loading. While the R-IV contract called for a wing-loading of less than 100 kg/m2, Messerschmitt felt this was unreasonable. With a low wing-loading and the engines available, a fighter would end up being slower than the bombers it was tasked with catching.

A fighter was designed primarily for high-speed flight. A smaller wing area was optimal for achieving high speed, but low-speed flight would suffer, as the smaller wing would require more airflow to generate enough lift to maintain flight. To compensate for this, the Bf 109 included advanced high-lift devices on the wings, including automatically-opening leading edge slats, and fairly large camber-changing flaps on the trailing edge. The slats increased the lift of the wing considerably when deployed, greatly improving the horizontal maneuverability of the aircraft, as several Luftwaffe veterans, such as Erwin Leykauf, attest.[24][25] Messerschmitt also included ailerons that 'drooped' when the flaps were lowered (F series and later the lower radiator flap operated as part of the flap system), thereby increasing the effective flap area. When deployed, these devices effectively increased the wings' coefficient of lift.

Fighters with liquid-cooled engines were vulnerable to hits in the cooling system. For this reason, on later Bf 109 F, G, and K models, the two coolant radiators were equipped with a cut-off system. If one radiator leaked, it was possible to fly on the second, or to fly for at least five minutes with both closed.[26][27][28][29]

In 1943, Oberfeldwebel Edmund Roßmann got lost and landed behind Soviet lines. He agreed to show the Soviets how to service the plane. Soviet machine gun technician Viktor M. Sinaisky recalled: The Messer was a very well designed plane. First, it had an engine of an inverted type, so it could not be knocked out from below. It also had two water radiators with a cut-off system: if one radiator leaked you could fly on the second or close both down and fly at least five minutes more. The pilot was protected by armour-plate from the back, and the fuel tank was also behind armour. Our planes had fuel tanks in the centre of their wings: that's why our pilot got burnt. What else did I like about the Messer? It was highly automatic and thus easy to fly. It also employed an electrical pitch regulator, which our planes didn't have. Our propeller system, with variable pitch was hydraulic, making it impossible to change pitch without engine running. If, God forbid, you turned off the engine at high pitch, it was impossible to turn the propeller and was very hard to start the engine again. Finally, the German ammo counter was also a great thing.[29]

Armament and gondola cannons

Reflecting Messerschmitt's belief in low-weight, low-drag, simple monoplanes, the armament was placed in the fuselage. This kept the wings very thin and light. Two synchronized machine guns were mounted in the cowling, firing over the top of the engine and through the propeller arc. An alternative arrangement was also designed, consisting of a single autocannon firing through a blast tube between the cylinder banks of the engine, known as a Motorkanone mount in German.[7][nb 3] This was also the choice of armament layout on some contemporary monoplane fighters, such as the French Dewoitine D.520, or the American Bell P-39 Airacobra, and dated back to World War I's small run of SPAD S.XII moteur-canon, 37 mm cannon-armed fighters in France.

When it was discovered in 1937 that the RAF was planning eight-gun batteries for its new Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire fighters, it was decided that the Bf 109 should be more heavily armed. The problem was that the only place available to mount additional guns was in the wings. Only one spot was available in each wing, between the wheel well and slats, with room for only one gun, either a 7.92 mm MG 17 machine gun, or a 20 mm MG FF or MG FF/M cannon.[31]

The first version of the 109 to have wing guns was the C-1, which had one MG 17 in each wing. To avoid redesigning the wing to accommodate large ammunition boxes and access hatches, an unusual ammunition feed was devised whereby a continuous belt holding 500 rounds was fed along chutes out to the wing tip, around a roller and then back along the wing, forward and beneath the gun breech, to the wing root, where it coursed around another roller and back to the weapon.[31]

The gun barrel was placed in a long, large-diameter tube located between the spar and the leading edge. The tube channeled cooling air around the barrel and breech, exhausting out of a slot at the rear of the wing. The installation was so cramped that parts of the MG 17's breech mechanism extended into an opening created in the flap structure.[31]

The much longer and heavier MG FF had to be mounted farther along the wing in an outer bay. A large hole was cut through the spar allowing the cannon to be fitted with the ammunition feed forward of the spar, while the breech block projected rearward through the spar. A 60-round ammunition drum was placed in a space closer to the wing root causing a bulge in the underside. A small hatch was incorporated in the bulge to allow access for changing the drum. The entire weapon could be removed for servicing by removing a leading edge panel.[31]

From the 109F-series onwards, guns were no longer carried inside the wings. Instead, the Bf 109F had a 20 mm gun firing through the propeller shaft. The change was disliked by leading fighter pilots such as Adolf Galland and Walter Oesau, but others such as Werner Mölders considered the single nose-mounted gun to compensate well for the loss of the two wing guns.[32] Galland had his Bf 109F-2 field-modified with a 20 mm MG FF/M autocannon, the '/M' suffix indicating the capability of firing thin-walled 20mm Minengeschoss shells, installed internally in each wing.[nb 4]

In place of internal wing armament, additional firepower was provided through a pair of 20 mm MG 151/20 cannons installed in conformal gun pods under the wings. The conformal gun pods, exclusive of ammunition, weighed 135 kg (298 lb);[33] and 135 to 145 rounds were provided per gun. The total weight, including ammunition, was 215 kg.[33] Installation of the under-wing gun pods was a simple task that could be quickly performed by the unit's armourers, and the gun pods imposed a reduction of speed of only 8 km/h (5 mph).[33] By comparison, the installed weight of a similar armament of two 20 mm MG 151/20 cannon inside the wings of the Fw 190A-4/U8 was 130 kg (287 lb), without ammunition.[34]

Although the additional armament increased the fighter's potency as a bomber destroyer, it had an adverse effect on the handling qualities, reducing its performance in fighter-versus-fighter combat and accentuating the tendency of the fighter to swing pendulum-fashion in flight.[32][35]

Some of the projected 109K-series models, such as the K-6, were designed to carry 30 mm (1.18 in) MK 108 cannons in the wings.[36]

Designation and nicknames

Originally the aircraft was designated as Bf 109 by the RLM, since the design was submitted by the Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (literally 'Bavarian Aircraft Works', meaning 'Bavarian Aircraft Factory'; sometimes abbreviated B.F.W.,[37] akin to BMW) during 1935. The company was renamed Messerschmitt AG after 11 July 1938 when Erhard Milch finally allowed Willy Messerschmitt to acquire the company. All Messerschmitt aircraft that originated after that date, such as the Me 210, were to carry the 'Me' designation. Despite regulations by the RLM, wartime documents from Messerschmitt AG, RLM and Luftwaffe loss and strength reports continued to use both designations, sometimes even on the same page.[38]

All extant airframes bear the official[39] 'Bf 109' designation on their identification plates, including the final K-4 models.[40] The aircraft was often referred to by the folk-designation, 'Me 109', particularly by the Allies.

The aircraft was often nicknamed Messer by its operators and opponents alike; the name was not only an abbreviation of the manufacturer, but also the German word for 'knife'. In Finland, the Bf 109 was known as Mersu, although this was originally the Finnish nickname for Mercedes-Benz cars.

Soviet aviators nicknamed the Bf 109 'the skinny one' (худо́й, khudoy), for its sleek appearance compared, for example, to the more robust Fw 190.

The names 'Anton', 'Berta', 'Caesar', 'Dora', 'Emil', 'Friedrich', 'Gustav', and 'Kurfürst' were derived from the variant's official letter designation (e.g. Bf 109G – 'Gustav'), based on the German spelling alphabet of World War II, a practice that was also used for other German aircraft designs.[41] The G-6 variant was nicknamed by Luftwaffe personnel as Die Beule ('the bump/bulge') because of the cowling's characteristic, bulging covers for the breeches of the 13 mm (.51 in) MG 131 machine guns, with the separate Beule covers eliminated by the time of the G-10 model's introduction of a subtly reshaped upper cowling.

Record-setting flights

In July 1937, not long after the public debut of the new fighter, three Bf 109Bs took part in the Flugmeeting airshow in Zürich under the command of Major Seidemann. They won in several categories: First prize in a speed race over a 202 km course, first prize in the class A category in the international Alpenrundflug for military aircraft, and victory in the international Patrouillenflug category.[17] On 11 November 1937, the Bf 109 V13, D-IPKY flown by Messerschmitt's chief pilot Dr. Hermann Wurster, powered by a 1,230 kW (1,650 hp) DB 601R racing engine, set a new world air speed record for landplanes with piston engines of 610.95 km/h (379.62 mph), winning the title for Germany for the first time. Converted from a Bf 109D, the V13 had been fitted with a special racing DB 601R engine that could deliver 1,230 kW (1,650 hp) for short periods.[42][43][nb 5]

Heinkel, having had the He 112 rejected in the design competition of 1936, designed and built the He 100. On 6 June 1938, the He 100 V3, flown by Ernst Udet, captured the record with a speed of 634.7 km/h (394.4 mph). On 30 March 1939, test pilot Hans Dieterle surpassed that record, reaching 746.61 km/h (463.92 mph) with the He 100 V8. Messerschmitt, however, soon regained the lead when, on 26 April 1939, Flugkapitän Fritz Wendel, flying the Me 209 V1, set a new record of 755.14 km/h (469.22 mph). For propaganda purposes, the Me 209 V1 aircraft (possibly from its post-July 1938 first flight date) was given the designation Me 109R, with the later prefix, never used for wartime Bf 109 fighters.[44] The Me 209 V1 was powered by the DB 601ARJ, producing 1,156 kW (1,550 hp), but capable of reaching 1,715 kW (2,300 hp). This world record for a piston-engined aircraft was to stand until 1969,[45] when Darryl Greenamyer's modified Grumman F8F Bearcat, Conquest I, broke it with a 777 km/h (483 mph) record speed.[46]

Variants

When the Bf 109 was designed in 1934, by a team led by Willy Messerschmitt and Robert Lusser,[47] its primary role was that of a high-speed, short range interceptor.[48] It used the most advanced aerodynamics of the time and embodied advanced structural design which was ahead of its contemporaries.[49] In the early years of the war, the Bf 109 was the only single-engined fighter operated by the Luftwaffe, until the appearance of the Fw 190. The 109 remained in production from 1937 through 1945 in many different variants and sub-variants. The primary engines used were the Daimler-Benz DB 601 and DB 605, though the Junkers Jumo 210 powered most of the pre-war variants. The most-produced Bf 109 model was the 109G series (more than a third of all 109s built were the G-6 series, 12,000 units being manufactured from March 1943 until the end of the war).[50] The initial production models of the A, B, C and D series were powered by the relatively low-powered, 670–700 PS (660–690 HP) Junkers Jumo 210 series engines. A few prototypes of these early aircraft were converted to use the more powerful DB 600.[51]

The first redesign came with the E series, including the naval variant, the Bf 109T (T standing for Träger, carrier). The Bf 109E (Emil) introduced structural changes to accommodate the heavier and more powerful 1,100 PS (1,085 HP) Daimler-Benz DB 601 engine, heavier armament and increased fuel capacity. Partly due to its limited 300 km (186 mile) combat radius on internal fuel alone, resulting from its 660 km (410 mile) range limit, later variants of the E series had a fuselage ordnance rack for fighter-bomber operations or provision for a long-range, standardized 300 litre (79 US gallon) drop-tank and used the DB 601N engine of higher power output.[5][52] The 109E first saw service with the 'Condor Legion' during the last phase of the Spanish Civil War and was the main variant from the beginning of World War II until mid-1941 when the 109F replaced it in the pure fighter role.[53] (Eight 109Es were assembled in Switzerland in 1946 by the Dornier-Werke, using licence built airframes; a ninth airframe was assembled using spare parts.)[54]

The second big redesign during 1939–40 gave birth to the F series. The Friedrich had new wings, cooling system and fuselage aerodynamics, with the 1,175 PS (1,159 HP) DB 601N (F-1, F-2) or the 1,350 PS (1,332 HP) DB 601E (F-3, F-4). Considered by many as the high-water mark of Bf 109 development, the F series abandoned the wing cannon and concentrated all armament in the forward fuselage with a pair of synchronized machine guns above and a single 15 or 20 mm Motorkanone-mount cannon behind the engine, the latter firing between the cylinder banks and through the propeller hub, itself covered by a more streamlined, half-elliptical shaped spinner that better matched the streamlining of the reshaped cowling, abandoning the smaller, conical spinner of the Emil subtype. The F-type also omitted the earlier stabilizer lift strut on either side of the tail. The improved aerodynamics were used by all later variants. Some Bf 109Fs were used late in the Battle of Britain in 1940 but the variant came into common use only in the first half of 1941.[55]

The G series, or Gustav, was introduced in mid-1942. Its initial variants (G-1 through G-4) differed only in minor details from the Bf 109F, most notably in the more powerful 1,475 PS (1,455 HP) DB 605 engine. Odd-numbered variants were built as high-altitude fighters with a pressurized cockpit and GM-1 boost, while even-numbered variants were un-pressurized, air superiority fighters and fighter-bombers. Long-range photo-reconnaissance variants also existed. The later G series (G-5 through G-14) was produced in a multitude of variants, with uprated armament and provision for kits of packaged, generally factory-installed parts known as Umrüst-Bausätze (usually contracted to Umbau) and adding a '/U' suffix to the aircraft designation when installed. Field kits known as Rüstsätze were also available for the G-series but those did not change the aircraft title. By early 1944, tactical requirements resulted in the addition of MW-50 water injection boost and high-performance superchargers, boosting engine output to 1,800–2,000 PS (1,775–1,973 HP). From early 1944, some G-2s, G-3s, G-4s and G-6s were converted to two-seat trainers, known as G-12s. An instructor's cockpit was added behind the original cockpit and both were covered by an elongated, glazed canopy.[56]

The final production version of the Bf 109 was the K series or Kurfürst, introduced in late 1944, powered by the DB 605D engine with up to 2,000 PS (1,973 HP). Though externally akin to the late production Bf 109G series, a large number of internal changes and aerodynamic improvements was incorporated that improved its effectiveness and remedied flaws, keeping it competitive with the latest Allied and Soviet fighters.[6][57] The Bf 109's outstanding rate of climb was superior to many Allied adversaries including the P-51D Mustang, Spitfire Mk. XIV and Hawker Tempest Mk. V.[58]

After the war, the 109 was built in Czechoslovakia, as the Avia S-99 and Avia S-199 (with twenty-five S-199s serving with Israel in 1948) and in Spain as the Hispano Aviación Ha 1109 and Ha 1112.[59]

Production

Total Bf 109 production was 33,984 units;[2] wartime production (September 1939 to May 1945) was 30,573 units. Fighter production totalled 47% of all German aircraft production, and the Bf 109 accounted for 57% of all German fighter types produced.[60] A total of 2,193 Bf 109 A–E was built prewar, from 1936 to August 1939.

In January 1943, as part of an effort to increase fighter production, Messerschmitt licensed an SS-owned company, DEST, to manufacture Bf 109 parts at Flossenbürg concentration camp. Messerschmitt provided skilled technicians, raw materials, and tools and the SS provided prisoners, in a deal that proved highly profitable for both parties. Production at Flossenbürg started in February.[61] The number of prisoners working for Messerschmitt increased greatly after the bombing of Messerschmitt's Regensburg plant on 17 August 1943.[62] Erla, a subcontractor of Messerschmitt, established Flossenbürg subcamps to support its production: a subcamp at Johangeorgenstadt, established in December 1943, to produce tailplanes for the Bf 109, and another subcamp at Mülsen-St. Micheln which produced Bf 109 wings, in January 1944.[63] The Flossenbürg camp system had become a key supplier of Bf 109 parts by February 1944, when Messerschmitt's Regensburg plant was bombed again during 'Big Week'. Increased production at Flossenbürg was essential to restoring production in the aftermath of the attack.[63]

After the August 1943 Regensburg raid, some Bf 109 production was relocated to Gusen in Austria,[64][65] where the average life expectancy was six months.[66] In order to make the new production facilities bomb-proof, other prisoners were forced to build tunnels so that production could be relocated underground. Many died while performing this hazardous duty.[67] By mid-1944, more than a third of the production at the Regensburg factory originated in Flossenbürg and Gusen alone; only the final assembly was done in Regensburg.[64][63] Separately, Erla employed thousands of concentration camp prisoners at Buchenwald on 109 production.[68] Forced labor at Buchenwald produced about 300 Bf 109 fuselages, tails, and wings before the end of the war.[68]

Some 865 Bf 109G derivatives were manufactured postwar under licence as Czechoslovak-built Avia S-99 and S-199s, with the production ending in 1948.[3] Production of the Spanish-built Hispano Aviación HA-1109 and HA-1112 Buchons ended in 1958.[3]

New-production Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters, 1936–45.[69]

Factory, location Up to 1939 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945* Totals* Messerschmitt, Regensburg 203 486 2,164 6,329 1,241 10,423 Arado, Warnemünde 370 370 Erla Maschinenwerke, Leipzig 683 875 2,015 4,472 1,018 9,063 Fieseler, Kassel 155 155 W.N.F., Wiener Neustadt 836 1,297 2,200 3,081 541 7,892 Győri Vagon- és Gépgyár, Győr 39 270 309 AGO, Oschersleben (switched to Fw 190A production) 381 381 Totals 1,860 1,540 1,868 2,628 2,658 6,418 14,152 2,800 33,984 * Production up to end of March 1945 only.

Operational history

The first Bf 109As served in the Spanish Civil War. By September 1939, the Bf 109 had become the main fighter of the Luftwaffe, replacing the biplane fighters, and was instrumental in gaining air superiority for the Wehrmacht during the early stages of the war. During the Battle of Britain, it was pressed into the role of escort fighter, a role for which it was not originally designed, and it was widely employed as a fighter-bomber, as well as a photo-reconnaissance platform. Despite mixed results over Britain, with the introduction of the improved Bf 109F in early 1941, the type again proved to be an effective fighter during the Invasion of Yugoslavia (where it was used by both sides), the Battle of Crete, Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the USSR, and the Siege of Malta.

In 1942, it began to be partially replaced in Western Europe by a new German fighter, the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, but it continued to serve in a multitude of roles on the Eastern Front and in the Defense of the Reich, as well as in the Mediterranean Theatre of Operations and with Erwin Rommel's Afrikakorps. It was also supplied to several of Germany's allies, including Finland, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia and Slovakia.

More aerial kills were made with the Bf 109 than any other aircraft of World War II.[70] Many of the aerial victories were accomplished against poorly trained and badly organized Soviet forces in 1941 during Operation Barbarossa. The Soviets lost 21,200 aircraft at this time, about half to combat.[71] If shot down, the Luftwaffe pilots might land or parachute to friendly territory and return to fight again. Later in the war, when Allied victories began to bring the fight closer, and then to German territory, bombing raids supplied plenty of targets for the Luftwaffe. This unique combination of events — until a major change in American fighter tactics occurred very early in 1944, that steadily gave the USAAF daylight air supremacy over the Reich — led to the highest-ever individual pilot victory scores.[72] One hundred and five Bf 109 pilots were each credited with the destruction of 100 or more enemy aircraft.[nb 6] Thirteen of these men scored more than 200 kills, while two scored more than 300. Altogether, this group of pilots was credited with a total of nearly 15,000 kills.[70] Though no official 'ace' status existed in the Luftwaffe (unofficially, the term Experte (expert) was used for an experienced pilot irrespective of his number of kills), using the Allied definition of pilots who scored five or more kills, more than 2,500 Luftwaffe fighter pilots were considered aces in World War II.[73] Against the Soviets, Finnish-flown Bf 109Gs claimed a victory ratio of 25:1.[74]

Bf 109s remained in foreign service for many years after World War II. The Swiss used their Bf 109Gs well into the 1950s. The Finnish Air Force did not retire their Bf 109Gs until March 1954. Romania used its Bf 109s until 1955. The Spanish Hispanos flew even longer. Some were still in service in the late 1960s. They appeared in films (notably Battle of Britain) playing the role of Bf 109Es. Some Hispano airframes were sold to museums, which rebuilt them as Bf 109s.

Operators

Note, this list includes operators who used Bf 109s for active service or combat. It does not include the United States, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union, which all operated small numbers of captured aircraft for testing and evaluation (see: Messerschmitt Bf 109 operational history#Allied Bf 109s).

Bulgaria:

The Bulgarian Air Force operated 19 E-3s and 145 G-2/-6/-10s.

Independent State of Croatia:

Zrakoplovstvo Nezavisne Države Hrvatske operated over 50 Bf 109s, including E-4, F-2, G-2/-6/-10 and Ks.

Czechoslovakia:

Czechoslovak Air Force operated captured aircraft and continued building Messerschmitt Bf 109Gs after the war under the Avia S-99 name, but soon ran out of the 109's Daimler-Benz DB 605 engine after many were destroyed during an explosion at a warehouse in Krásné Březno.

Finland:

Finnish Air Force ordered 162 aircraft (48 G-2s, 111 G-6s and three G-8s) from Germany, but 3 were destroyed during transit, leaving the FAF with 159 Bf 109s. FAF pilots had 663 air victories during 1943–44 with Bf-109 G's and lost 34 in combat (20 shot down by enemy aircraft). 23 were non-combat losses and other write-offs. 102 Bf-109 G survived the war.

Nazi Germany:

Luftwaffe was the main operator of the Bf 109.

Hungary:

Royal Hungarian Air Force operated 3 D-1s, 50 E-3/-4s, 66 F-4s and ~490 G-2/-4/-6/-8/-10/-14s.[75]

Israel:

Israeli Air Force operated the Avia S-199 derivative, bought from Czechoslovakia. Despite the type's shortcomings the Israelis scored 8 victories. Egypt and Syria claimed 4 S-199 kills, and 1 probable.[76]

Italy:

Regia Aeronautica operated several tens of Bf 109s in the first half of 1943.[77]

Italian Social Republic:

Aeronautica Nazionale Repubblicana operated 300 G-6/-10/-14s and two G-12s; three K-4s were also received.

Japan:

Imperial Japanese Army Air Force purchased 5 E-7s in 1941. The aircraft were used for tests and trials.[78]

Romania:

Royal Romanian Air Force operated 50 E-3/4s, 19 E-7s, 2 F-2s, 5 F-4s and at least 235+ G-2/G-4/G-6/-8s plus 75 IAR built 109G-6a.

Romanian Air Force – Postwar.

Slovakia Slovak Republic:

Slovak Air Force operated 16 E-3s, 14 E-7s and 30 G-6s.

Slovak Insurgent Air Force operated 3 G-6s during the Slovak National Uprising.

Spanish State:

Spanish Air Force operated some D-1s, E-3s and 15 F-4s, and may have received several older B-types. Volunteers of Escuadrilla Azul on the Eastern Front operated E-4, E-7, E-7/B, F-2, F-4 (belonged in JG-27 under the command of Luftflotte 2, until April 1943) among G-4 and G-6 (detached in JG-51 under the command Luftflotte 4, until June 1944). A variant under license by the name Hispano Aviación HA-1112 was produced until 1958.

Switzerland:

Swiss Air Force operated 10 D-1s, 89 E-3a variants, 2 F-4s and 14 G-6s.

Yugoslavia:

Royal Yugoslav Air Force operated 73 E-3a variants.

SFR Yugoslav Air Force operated several ex-NDH and Bulgarian Bf 109Gs.Messerschmitt Bf 109's Variants

Due to the Messerschmitt Bf 109's versatility and time in service with both the Luftwaffe and other foreign air forces, numerous variants were produced over the eight years of service with the Luftwaffe and even more were produced by its foreign users.

Originally the aircraft was designated as Bf 109 by the RLM, since the design was submitted by the Bayerische Flugzeugwerke ("Bavarian Aircraft Works") during 1935. BFG was renamed Messerschmitt AG after 11 July 1938 when Erhard Milch finally allowed Willy Messerschmitt to acquire the company. All Messerschmitt aircraft that originated after that date, such as the Me 210, were to carry the "Me" designation.

The names "Anton", "Berta", "Caesar", "Dora", "Emil", "Friedrich", "Gustav" and "Kurfurst" were derived from the variant's official letter designation (e.g. Bf 109G – "Gustav"), based on the German spelling alphabet of World War II, a practice that was also used for other German aircraft designs.

When the Bf 109 was designed in 1934 by a team led by Willy Messerschmitt and Robert Lusser, its primary role was that of a high-speed, short range interceptor. It utilized the most advanced aerodynamics of the time and embodied advanced structural design which was ahead of its contemporaries. In the years of the Blitzkrieg, the Bf 109 was the only single-engine fighter operated by the Luftwaffe, until the appearance of the Fw 190.

The 109 remained in production from 1937 through 1945 in many different variants and sub-variants. The primary engines used were the Daimler-Benz DB 601 and DB 605, though the Junkers Jumo 210 powered most of the pre-war variants. The most-produced Bf 109 model was the 109 G series (more than a third of all 109s built were the G-6 series, some 12,000 units being manufactured from March 1943 until the end of the war).

The Bf 109 K was the last of the series to see operational duty and the last in the Bf 109 evolutionary line. The K series was a response to the bewildering array of series, models, modification kits and factory conversions for the Bf 109, which made production and maintenance complicated and costly – something Germany could ill-afford late in the war. Work on the new version began in the spring of 1943, and the prototype was ready by the autumn of that year. Series production started in August 1944 with the K-4 model, due to changes in the design and delays with the new DB 605D powerplant. The K-4 was the only version to be mass-produced.

Externally the K series could be identified by changes in the locations of the radio equipment hatch, which was moved forward and to a higher position between frames four and five, and the filler point for the fuselage fuel tank, which was moved forward to a location between frames two and three. The rudder was fitted as standard with a Flettner tab and two fixed tabs although some rare examples were not fitted with the fixed tabs. All K-4s were to be fitted with a long retractable tailwheel with two small clamshell doors covering the recess when the tail-wheel was retracted.

The wings featured the large rectangular fairings for the large 660x190 mm main wheels. Flettner tabs for the ailerons were also to be fitted to serial production aircraft to reduce control forces, but were extremely rare, with the majority of the K-4s using the same aileron system as the G series.

Armament of the K-4 consisted of a 30 mm (1.18 in) MK 108 engine-mounted cannon (Motorkanone) with 65 rounds, and two 13 mm (.51 in) MG 131s in the nose with 300 RPG although some K-4s were fitted with the MG 151/20 as the Motorkanone.

Power was provided in production K-4s by a Daimler-Benz DB 605DB or DC engine (very early K-4s used the earlier DM). A wide-chord, three bladed VDM 9-12159A propeller of 3 m diameter was used, as on the G-6/AS, G-14/AS and G-10.

Using MW 50 and maximum boost the Bf 109 K-4 was the fastest 109 of World War II, reaching a maximum speed of 710 km/h (440 mph) at 7,500 m (24,610 ft.) altitude. Without MW 50 and using 1.80 ATA the K-4 reached 670 km/h (416 mph) at 9,000 m (26,528 ft). The Initial Rate of climb was 2,775 ft. (850 m)/min, without MW 50, and 3,563 ft. (1,090 m)/min, using MW 50.

The Bf 109 remained comparable to opposing fighters until the end of the war. However, the deteriorating ability of the thousands of novice Luftwaffe pilots by this stage of the war meant the 109's strengths were of little value against the numerous and well-trained Allied fighter pilots.

Bf 109 A/B/C/D

The 109 was a dream, the non plus ultra. Of course, everyone wanted to fly it as soon as possible.

— Gunther Rall, Luftwaffe ace with 275 victories.[1]The Bf 109A was the first version of the Bf 109. Armament was initially planned to be just two cowl-mounted 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17 machine guns. However, possibly due to the introduction of the Hurricane and Spitfire, each with eight 7.7 mm (.303 in) machine guns, experiments were carried out with a third machine gun firing through the propeller shaft.[2] V4 and some A-0 were powered by a 640 PS (631 hp, 471 kW) Junkers Jumo 210B engine driving a two-blade fixed-pitch propeller, but production was changed to the 670 PS (661 hp, 493 kW) Jumo 210D as soon as it became available. The A-0 was not of a uniform type; there were several changes in their appearance. Visible changes included engine, cockpit and machine gun ventilation holes/slats, and the location of the oil cooler was changed several times to prevent overheating. Many of these Bf 109 A-0 served with the Legion Condor and were often misidentified as B-series aircraft, and probably served in Spain with the tactical markings 6-1 to 6–16. One A-0, marked as 6–15, ran out of fuel and was forced to land behind enemy lines. It was captured by Republican troops on 11 November 1937 and later transferred to the Soviet Union for a closer inspection.[3] 6–15 incorporated several improvements from the Bf 109B production program and had been prepared to use a variable-pitch propeller although it had not been installed.

According to RLM documentation 22 aircraft were ordered and delivered with V4 as the A-series prototype.[4][5]

The first Bf 109 in serial production, the Bf 109 B-1, was fitted with the 670 PS (661 hp, 493 kW) Jumo 210D engine driving a two-bladed fixed-pitch propeller. During the production run a variable-pitch propeller was introduced and often retrofitted to older aircraft; these were then unofficially known as B-2s. The Bf 109B saw combat with the Legion Condor during the Spanish Civil War, although it was apparent that the armament was still inadequate. Several aircraft were produced with an engine-mounted machine gun but it was very unreliable, most likely because of engine vibrations and overheating. Thus the Bf 109 V8 was constructed to test the fitting of two more machine guns in the wings; however, results showed that the wing needed strengthening.[6] In the following V9 prototype, both wing guns were replaced by 20 mm MG FF cannons.[7]

A total of 341 Bf 109 B-1s were built by Messerschmitt, Fieseler, and the Erla Maschinenwerke.[8][9]

Production of the short-lived Bf 109C began in the spring of 1938.[10] The 109C was powered by a 700 PS (690 hp, 515 kW) Jumo 210G engine with direct fuel injection. Another important change was a strengthened wing, now carrying two more machine guns, giving four 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17s in total. The C-0s were pre-production aircraft, the C-1 was the production version, and the C-2 was an experimental version with an engine-mounted machine gun. The C-3 was planned with 20 mm MG FF cannons replacing the two MG 17s in the wings, but it is not known how many C-3s (if any) were built or converted. The C-4 was planned to have an engine-mounted Motorkanone MG FF, but this variant was not produced.[11]

A total of 58 Bf 109Cs of all versions were built by Messerschmitt.[8][9]

The next model, the V10 prototype, was identical to the V8, except for its Jumo 210G engine. The V10, V11, V12 and V13 prototypes were built using Bf 109B airframes, and tested the DB 600A engine with the hope of increasing the performance of the aircraft. The DB 600A was dropped as the improved DB601A with direct fuel injection was soon to become available.

Developed from the V10 and V13 prototypes, the Bf 109D was the standard version of the Bf 109 in service with the Luftwaffe just before the start of World War II. Despite this, the type saw only limited service during the war, as all of the 235 Bf 109Ds still in Luftwaffe service at the beginning of the Poland Campaign were rapidly taken out of service and replaced by the Bf 109E, except in some night fighter units where some examples were used into early 1940. Variants included the D-0 and D-1 models, both having a Junkers Jumo 210D engine and armed with two wing-mounted and two nose-mounted 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17s. The D-2 was an experimental version with an engine-mounted machine gun, but as previously tried, this installation failed. The D-3 was similar to the C-3 but with two 20 mm MG FFs in the wings.

A total of 647 Bf 109Ds of all versions were built by Focke-Wulf, Erla, Fieseler, Arado and AGO.[12][13] Messerschmitt is listed as having produced only four Bf 109Ds, probably the D-0 preproduction series with the serial production transferred to the licensed manufacturers. Several Bf 109Ds were sold to Hungary. Switzerland bought 10 109D-1s (Serial Numbers from 2301 until 2310) which had been built by the Arado-Flugzeugwerke GmbH factory located in Warnemünde.

Bf 109E

In late 1938, the Bf 109E entered production. To improve on the performance afforded by the 441–515 kW (600–700 PS) Jumo 210, the larger, longer Daimler-Benz DB 601A engine was used, yielding an extra 223 kW (300 PS) at the cost of an additional 181 kg (400 lb). A much bigger cooling area was needed to disperse the extra heat generated by the DB 601 and this led to the first major redesign of the basic airframe. Enlarging the existing nose mounted radiator sufficiently to cool the engine would have created extra weight and drag, negating some of the performance gains afforded by the increased power, so it was decided to move the main radiators to the undersurfaces of the wings immediately outboard of the junction of the wing root and wing panel, just forward of the trailing edges' inner ends, leaving the oil cooler under the nose in a small, streamlined duct. The new radiator position also had the effect of counterbalancing the extra weight and length of the DB 601, which drove a heavier three-bladed Vereinigte Deutsche Metallwerke (VDM)-made propeller.[14]

To incorporate the new radiators, the wings were almost completely redesigned and reinforced, with several inboard ribs behind the spar being cut down to make room for the radiator ducting. Because the radiators were mounted near the trailing edge of the wing, coinciding with the increased speed of the airflow accelerating around the wing camber, cooling was more effective than that of the Jumo engined 109s, albeit at the cost of extra ducting and piping, which was vulnerable to damage. The lowered undercarriage could throw up mud and debris on wet airfields, potentially clogging the radiators.[15] To test the new 1,100 PS (1,085 hp, 809 kW) DB 601A engine, two more prototypes (V14 and V15) were built, each differing in their armament. While the V14 was armed with two 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17s above the engine and one 20 mm MG FF in each wing, the V15 was just fitted with the two MG 17s mounted above the engine.[16] After test fights, the V14 was considered more promising and a pre-production batch of 10 E-0 was ordered. Batches of both E-1 and E-3 variants were shipped to Spain for evaluation, and first saw combat during the final phases of the Spanish Civil War.

E-1

The E-1 production version kept two 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17s above the engine and two more in the wings. Later, many were modified to the E-3 armament standard. The E-1B was a small batch of E-1s that became the first operational Bf 109 fighter bomber, or Jagdbomber (usually abbreviated to Jabo). These were fitted with either an ETC 500 bomb rack, carrying one 250 kg (550 lb) bomb, or four 50 kg (110 lb) bombs. The E-1 was also fitted with the Reflexvisier 'Revi' gunsight. Communications equipment was the FuG 7 Funkgerät 7 (radio set) short-range radio apparatus, effective to ranges of 48–56 km (30–35 mi). A total of 1,183 E-1 were built, 110 of them were E-1/B.[12][13]

E-2

Only very limited numbers of the E-2 variant were built, for which the V20 prototype served as basis. It was armed with two wing mounted, and one engine mounted Motorkanone MG FF cannon, which gave considerable trouble in service, as well as two synchronized MG 17s cowl machine guns. In August 1940, II./JG 27 was operating this type.[17][18]

E-3

To improve the performance of the Bf 109E, the last two real prototypes (V16 and V17) were constructed. These received some structural improvements and more powerful armament. Both were the basis of the Bf 109 E-3 version. The E-3 was armed with the two MG 17s above the engine and one MG FF cannon in each wing.[19][20] A total of 1,276 E-3 were built, including 83 E-3a export versions.[12][13]

E-4

The E-3 was replaced by the E-4 (with many airframes being upgraded to E-4 standards starting at the beginning of the Battle of Britain), which was different in some small details, most notably by using the modified 20 mm MG-FF/M wing cannon and having improved head armour for the pilot. With the MG FF/M, it was possible to fire a new and improved type of explosive shell, called Minengeschoß (or 'mine-shell'), which was made using drawn steel (the same way brass cartridges are made) instead of being cast as was the usual practice. This resulted in a shell with a thin but strong wall, which had a larger cavity in which to pack a much larger explosive charge than was otherwise possible. The new shell required modifications to the MG FF's mechanism due to the different recoil characteristics, hence the MG FF/M designation.

The cockpit canopy was also revised to an easier-to-produce, 'squared-off' design, which also helped improve the pilot's field of view. This canopy, which was also retrofitted to many E-1s and E-3s, was largely unchanged until the introduction of a welded, heavy-framed canopy on the G series in the autumn of 1942. The E-4 would be the basis for all further Bf 109E developments. Some E-4 and later models received a further improved 1,175 PS (1,159 hp, 864 kW) DB601N high-altitude engine; known as the E-4/N; owing to priority being given to equipping Bf 110s with this engine, one fighter gruppe was converted to this version, starting in July 1940.[21] The E-4 was also available as a fighter-bomber with equipment very similar to the previous E-1/B. It was known as E-4/B (DB 601Aa engine) and E-4/BN (DB 601N engine). A total of 561 of all E-4 versions were built,[13] including 496 E-4s built as such: 250 E-4, 211 E-4/B, 15 E-4/N and 20 E-4/BN.[12]

E-5, E-6

The E-5 and E-6 were both reconnaissance variants with a camera installation behind the cockpit. The E-5 was a reconnaissance variant of the E-3, the E-6 was a reconnaissance variant of the E-4/N. Twenty-nine E-5s were built and nine E-6s were ordered.[12]

E-7

The E-7 was the next major production variant, entering service and seeing combat at the end of August 1940.[22] One of the limitations of the earlier Bf 109Es was their short range of 660 km (410 mi) and limited endurance, as the design was originally conceived as a short-range interceptor.[23] The E-7 rectified this problem as it was the first Bf 109 subtype to be able to carry a drop tank, usually the standardized Luftwaffe 300 L (80 US gal) capacity unit mounted on a centre-line rack under the fuselage, which increased its range to 1,325 km (820 mi). Alternatively, a bomb could be fitted and the E-7 could be used as a Jabo fighter-bomber. Previous Emil subtypes were progressively retrofitted with the necessary fittings for carrying a drop tank from October 1940.[24] Early E-7s were fitted with the 1,100 PS DB 601A or 1,175 PS DB 601Aa engine, while late-production ones received 1,175 PS DB 601N engines with improved altitude performance – the latter was designated as E-7/N.[25] A total of 438 E-7s of all variants were built.[26]

Bf 109E variants and sub-variants

E-0: (Pre-production aircraft with 4 × 7.92 mm/.312 in MG 17 machine guns)

E-1: (Similar to E-0)

E-1/B: (Fighter-bomber version of E-1, usually with DB 601Aa)

E-2: (Limited production, additional Motorkanone engine mounted MG FF cannon, otherwise as E-3)

E-3: (Similar to E-1 but 2 × 20 mm MG FFs in the wings instead of the MG 17)

E-4: (Armour and structural improvements, change of MG FF cannons to MG FF/M. 'Square' canopy)

E-4/B: (Fighter-bomber version of E-4, 1 × 250 kg/550 lb bomb, usually with DB 601Aa)

E-4 trop: (Version of E-4 modified to serve in tropical regions)

E-4/N: (E-4 with DB601N engine)

E-4/BN: (Fighter-bomber version of E-4/N, 1 × 250 kg/550 lb bomb)

E-5: (Recon version of E-3, camera equipment, 2 × 7.92 mm/.312 in MG 17)

E-6: (Recon version of E-4/N, camera equipment, 2 × 7.92 mm/.312 in MG 17)

E-7: (Similar to E-4 but with optional 300 L drop tank)

E-7/N: (Similar to E-4/N but with optional 300 L tank)

E-7/NZ: (also known as E-7/Z, an E-7/N with additional GM-1 nitrous oxide injection system)

E-7/U2: (Ground attack variant of E-7 with additional armour)

E-8: (Long-range version of E-1 using drop tank installation of E-7, 4 × 7.92 mm/.312 in MG 17)

E-9: (Recon version of E-7/N, drop tank, camera equipment, 2 × 7.92 mm/.312 in MG 17)Bf 109T

Prior to the war, the Kriegsmarine had become fascinated with the idea of the aircraft carrier. Borrowing ideas from the British and Japanese (mainly Akagi), they started the construction of Graf Zeppelin as part of the rebuilding of the navy. The air group for the carrier was settled on Messerschmitt Bf 109T fighters and Ju 87C dive bombers. The suffix 'T' denotes Träger (carrier) in German use.[27]

Despite references to a Bf 109 T-0 version.[27] this version never existed. Seven earlier versions (Bf 109 B, Bf 109 C, Bf 109 E) were converted to test carrier equipment. This included adding a tail-hook, catapult fittings and increasing the wingspan to 11.08 m (36.35 ft). The ailerons were increased in span, as were the slats, and flap travel was increased. The wings were not modified to be folding since the ship Graf Zeppelin was designed around the intended aircraft, so the lifts could accommodate the Bf 109T with its 11 m (36 ft) wingspan. The wings could, however, be detached from the fuselage for transport purposes, as in every version of the Bf 109.[28][29][30]

Following flight tests, especially the catapult tests, 70 T-1 with DB601Ns were to be produced at Fieseler in Kassel, but after seven T-1s were built, the carrier project was cancelled. The remaining 63 of 70 T-1s were built as T-2s without carrier equipment and some of the T-1s may have been 'upgraded' to T-2 standard. It was found that the performance of the T-2 was closely comparable to the E-4/N and, because of its ability to take off and land in shorter distances, these fighters were assigned to I/JG.77, deployed in Norway on landing strips which were both short and subject to frequent, powerful cross-winds.[31] At the end of 1941 the unit was ordered to return their aircraft to Germany and received E-3s as replacements.[32] The armament of the Bf 109T consisted of two 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17s above the engine and one 20 mm MG FF/M cannon in each wing.[27]

Interest in Graf Zeppelin revived when the value of aircraft carriers became obvious, and in 1942 the ship was back in the yards for completion. By this time, the Bf 109T was hopelessly outdated and a new fighter would be needed. Messerschmitt responded with the updated Me 155A series, but work on the ship was again canceled and the Me 155 was later re-purposed as a high-altitude interceptor. Design work was transferred to Blohm & Voss and the aircraft was then known as the BV 155.

The Bf 109Ts were issued to several training units in 1943. Then, in April 1943, the Jagdstaffel Helgoland was formed[33] and operated from Düne until late 1943, when the unit transferred to Lista in south Norway. The unit was renamed as 11./JG 11 as of 30 November 1943[34] and the Bf 109Ts remained in operation until the summer of 1944, after which some were used in training units in Germany.

Bf 109F

Prototypes

Development of the new Bf 109 F airframe had begun in 1939. After February 1940, an improved engine, the Daimler-Benz DB 601E, was developed for use with the Bf 109. The engineers at the Messerschmitt facilities took two Bf 109 E-1 airframes and installed this new powerplant. The first two prototypes, V21 (Werknummer (Works number) or W.Nr 5602) and V22 (W.Nr 1800) kept the trapeziform wing shape from the E-1, but the span was reduced by 61 cm (2 ft) by 'clipping' the tips. Otherwise the wings incorporated the cooling system modifications described below. V22 also became the testbed for the pre-production DB 601E. The smaller wings had a detrimental effect on the handling so V23, Stammkennzeichen (factory Code)[Notes 1] CE+BP, W.Nr 5603, was fitted with new, semi-elliptical wingtips, becoming the standard wing planform for all future Bf 109 combat versions. The fourth prototype, V24 VK+AB, W.Nr 5604, flew with the clipped wings but featured a modified, 'elbow'-shaped supercharger air-intake, which was eventually adopted for production, and a deeper oil cooler bath beneath the cowling.[35] On all of these prototypes, the fuselage was cleaned up and the engine cowling modified to improve aerodynamics.

Aerodynamic improvements

Compared to the earlier Bf 109 E, the Bf 109 F was much improved aerodynamically. The engine cowling was redesigned to be smoother and more rounded. The enlarged propeller spinner, adapted from that of the new Messerschmitt Me 210, now blended smoothly into the new engine cowling.[36] Underneath the cowling was a revised, more streamlined oil cooler radiator and fairing. A new ejector exhaust arrangement was incorporated, and on later aircraft a metal shield was fitted over the left hand banks to deflect exhaust fumes away from the supercharger air-intake. The supercharger air-intake was, from the F-1 -series onwards, a rounded, 'elbow'-shaped design that protruded further out into the airstream. A new three-blade, light-alloy VDM propeller unit with a reduced diameter of 3 m (9 ft 8.5 in) was used. Propeller pitch was changed electrically, and was regulated by a constant-speed unit, though a manual override was still provided. Thanks to the improved aerodynamics, more fuel-efficient engines and the introduction of light-alloy versions of the standard Luftwaffe 300 litre drop tank, the Bf 109 F offered a much increased maximum range of 1,700 km (1,060 mi)[37] compared to the Bf 109 E's maximum range figure of only 660 km (410 miles) on internal fuel,[38] and with the E-7's provision for the 300 litre drop tank, a Bf 109E so equipped possessed double the range, to 1,325 km (820 mi).

The canopy stayed essentially the same as that of the E-4, although the handbook for the 'F' stipulated that the forward, lower triangular panel to starboard was to be replaced by a metal panel with a port for firing signal flares. Many F-1s and F-2s kept this section glazed. A two-piece, all-metal armour plate head shield was added, as on the E-4, to the hinged portion of the canopy, although some lacked the curved top section. A bullet-resistant windscreen could be fitted as an option.[39] The fuel tank was self-sealing, and around 1942 Bf 109Fs were retrofitted with additional armour made from layered light-alloy plate just aft of the pilot and fuel tank. The fuselage aft of the canopy remained essentially unchanged in its externals.

The tail section of the aircraft was redesigned as well. The rudder was slightly reduced in area and the symmetrical fin section changed to an airfoil shape, producing a sideways lift force that swung the tail slightly to the left. This helped increase the effectiveness of the rudder, and reduced the need for application of right rudder on takeoff to counteract torque effects from the engine and propeller. The conspicuous bracing struts were removed from the horizontal tailplanes which were relocated to slightly below and forward of their original positions. A semi-retractable tailwheel was fitted and the main undercarriage legs were raked forward by six degrees to improve the ground handling. An unexpected structural flaw of the wing and tail section was revealed when the first F-1s were rushed into service; some aircraft crashed or nearly crashed, with either the wing surface wrinkling or fracturing, or by the tail structure failing. In one such accident, the commander of JG 2 'Richthofen', Wilhelm Balthasar, lost his life when he was attacked by a Spitfire during a test flight. While making an evasive manoeuvre, the wings broke away and Balthasar was killed when his aircraft hit the ground. Slightly thicker wing skins and reinforced spars dealt with the wing problems. Tests were also carried out to find out why the tails had failed, and it was found that at certain engine settings a high-frequency oscillation in the tailplane spar was overlapped by harmonic vibrations from the engine; the combined effect being enough to cause structural failure at the rear fuselage/fin attachment point. Initially, two external stiffening plates were screwed onto the outer fuselage on each side, and later the entire structure was reinforced.[35]

The entire wing was redesigned, the most obvious change being the new quasi-elliptical wingtips, and the slight reduction of the aerodynamic area to 16.05 m² (172.76 ft²). Other features of the redesigned wings included new leading edge slats, which were slightly shorter but had a slightly increased chord; and new rounded, removable wingtips which changed the planview of the wings and increased the span slightly over that of the E-series. Frise-type ailerons replaced the plain ailerons of the previous models. The 2R1 profile was used with a thickness-to-chord ratio of 14.2% at the root reducing to 11.35% at the last rib. As before, dihedral was 6.53°.[36]