Fiat G.50 MM 3576 flown by Maggiore Mario Bonzano, commanding officer of Reparto Sperimentale G.50, (XXIII Gruppo Caccia), Aviazione Legionaria, Escalona, May 1939. This camouflage scheme was typical of the first 45 production aircraft, with Green and Brown blotches on a Sand background, and Light Grey lower surfaces. The oblique white band on fuselage was indicating the unit commander’s aircraft. During the few combat missions carried, the unit never engaged enemy planes. When the operations ceased it was involved in several propaganda parades celebrating victory, and a group command badge was painted white inside the black fuselage disc. In this case it should have been just referred to Bonzano's rank of Maggiore, considering that Maggiore Remondino was already and more properly carrying the same badge on his CR.32

Fiat G.50 MM 3586 of Reparto Sperimentale G.50, (XXIII Gruppo Caccia), Aviazione Legionaria, Escalona, May 1939. Standard camouflage scheme with Green and Brown blotches on Sand base, and Light Grey lower surfaces. This plane could be recognised by two large white dots painted inside the black fuselage disc. Even in this case it could have been a badge of rank (probably referred to a Tenente, maybe Del Prete) added for esthetical and propaganda reasons during the final parades attended by this unit after the war ended. Air parades were held on 15 April at Seville, on 9 May at Barajas, on 13 at Getafe, with a final fly-past over Madrid on 19 May. Not a single aircraft sent to Spain carried the landing gear doors, even if all of them maintained the faired tail wheel.

Image Source and description from Ali E Colori Italian Colours Fiat G 50 by La Bancarella Aeronautica Torino No 3 Page 5

Fiat G.50 MM 3580, of Reparto Sperimentale G.50. (XXIII Gruppo Caccia), Aviazione Legionaria, Escalona, April 1939. Three-tone camouflage scheme with Green and Brown blotches on Sand background. Lower surfaces Light Grey. After calling at Valenzuela, this unit reached Escalona on 14 March, being attached to the XXIII Gruppo Caccia, still mounted on Fiat CR.32s and led by Maggiore Aldo Remondino. Before war operations could be suspended on 1 April just a few mission could be carried from this base, where the famous “Ace of Clubs” group badge was added. Originally, the group badge, carried on a blue shield on the fuselage side, was of limited size, having to be later enlarged, probably for propaganda reasons. Even the Nationalist fuselage black disc was painted larger here than originally painted. The same type-number 1 previously assigned to Nieuport 52s, was painted red on G.50’s fuselage sides, beside black individual codes.

Image Source and description from Ali E Colori Italian Colours Fiat G 50 by La Bancarella Aeronautica Torino No 3 Page 4

Fiat G.50 MM 3575, flown by Tenente Enzo Martizza, Reparto Sperimentale G.50, Aviazione Legionaria, Reus, March 1939. Camouflage scheme was a three-tone with Green (Verde Mimetico 1) and Brown (Marrone Mimetico 1) blotches on Sand (Giallo Mimetico 1) background. Lower surfaces were Light Grey (Grigio Mimetico). This experimental unit had been formed at Guidonia in January 1939, to evaluate the new monoplane fighter. It received twelve aircraft from the first production batch, with the enclosed cockpit type. In February they were sent to Spain by sea-freight, just in time to be used in the final stages of the civil war. They were later reassembled at Reus airfield, arriving there on 27 February with the original camouflage, just completed by Nationalist insignia, including a plain black disc on fuselage sides, a large white cross above the wings and two narrow chord-wise black bands below, inboard of the white wing tips. A black St. Andrew’s Cross on white rudders completed the markings.

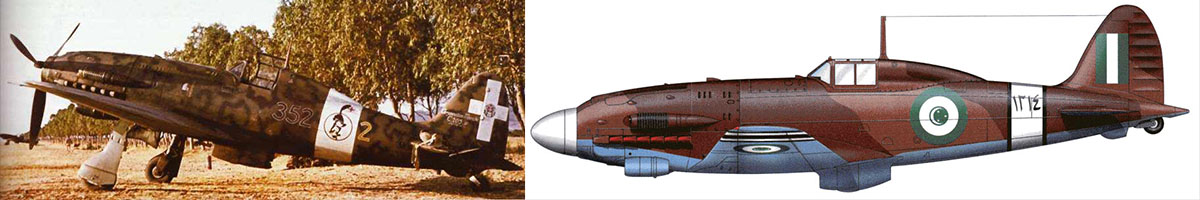

Fiat G.50 MM 3582 of Grupo de Caza 27. Ejercito del Aire. Nador. February 1943. The camouflage scheme consisted in Green and Brown blotches on a Sand base, with Light Grey undersurfaces. All of the twelve aircaft purchased from Italy were assigned to No.27 Fighter Group. The original Italian camouflage was never changed during the type's career, even if type and individual codes were later moved across the national black disc. The Falangist insignia inside the disc was later painted red. as it was usually carried in this colour by many other Spanish aircraft. In 1940 all wing nationalist insignia were replaced by new red-yellow-red roundels, being the colours of the House of Bourbon, adopted after the war for the national flag in stead of the republican tricolour. Early in June 1939 all G.50s of Grupo 27 had been posted to Nador, near Mellilla in the Spanish Morocco. On that airfield a few aircraft were still operational in 1943, when their use was limited to training duties.

Image Source and description from Ali E Colori Italian Colours Fiat G 50 by La Bancarella Aeronautica Torino No 3 Page 6

AirMagazine 22 Page 42-55

AirMagazine 22 Page 42-55

AirMagazine 22 Page 42-55

AirMagazine 22 Page 42-55

Fiat G.50 MM 3582 of Grupo de Caza 27, Aviacion Nacional, Sevillla-Tablada, June 1939. Standard camouflage scheme of Green and Brown blotches on a Sand base, with Light Grey lower surfaces. Before returning home the Italian pilots consigned their eleven surviving aircraft to the Nationalist Air Force. A twelfth plane was later sent from Italy completing the order, replacing Martizza’s aircaft that was destroyed during the war. All of them retained the original Italian camouflage with the only addition of a Spanish unit’s badge on fin, representing a hound dog. Even the joke an arrows symbol of the Falange movement was painted white inside the national black disc. Italian codes remained unchanged even if, on this particular plane, the paintwork was showing traces of retoucing where the Italian unit badge had been previously carried.

AirMagazine 22 Page 42-55

The Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War was a major conflict in Spain that started after an attempted coup detat committed by parts of the army against the government of the Second Spanish Republic. The Civil War devastated Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939, ending with the victory of the rebels and the founding of a dictatorship led by the Fascist General Francisco Franco and the defeat of the supporters of the Republic. Republicans (republicanos), gained the support of the Soviet Union and Mexico, while the followers of the rebellion, nacionales (Nationalists), received the support of the major European Axis powers, namely Italy, Germany, as well as neighbouring Portugal.

The war increased tensions in the lead-up to World War II and was largely seen as a possible war by proxy between the Communist Soviet Union and the Fascist Axis of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. In particular, tanks and bombing of cities from the air were features of the later war in Europe. The advent of the mass media allowed an unprecedented level of attention (Ernest Hemingway, Martha Gellhorn, George Orwell and Robert Capa all covered it) and so the war became notable for the passion and political division it inspired, and for atrocities committed on both sides of the conflict. Like other Civil Wars, the Spanish Civil War often pitted family members and trusted neighbors and friends against each other. Apart from the combatants, many civilians were killed for their political or religious views by both sides, and after the war ended in 1939, Republicans were at times persecuted by the victorious Nationalists.

Prelude to the war

Historical context

There were several reasons for the war, many of them long-term tensions that had escalated over the years.

The 19th Century was a turbulent one for Spain. The country had undergone several civil wars and revolts, carried out by both reformists and the conservatives, who tried to displace each other from power. A liberal tradition that first ascended to power with the Spanish Constitution of 1812 sought to abolish the absolutist monarchy of the old regime and to establish a liberal state. The most traditionalist sectors of the political sphere systematically tried to avert these reforms and to sustain the monarchy. The Carlists - supporters of Infante Carlos and his descendants - rallied to the cry of God, Country and King and fought for the cause of Spanish tradition (absolutism and Catholicism) against the liberalism and later the republicanism of the Spanish governments of the day. The Carlists, at times (including the Carlist Wars), allied with nationalists (not to be confused with the nationalists of the Civil War) attempting to restore the historic liberties (and broad regional autonomy) granted by the fueros of the Basque Country and Catalonia. Further, from the mid-19th century onwards, the liberals were outflanked on their left by socialists of various types and especially by anarchists, who were far stronger and more numerous in Spain than anywhere else in Europe aside from (possibly) Russia.

Los Cuatro Generales and Viva La Quince Brigada

Spain experienced a number of different systems of rule in the period between the Napoleonic wars of the early 19th century and the outbreak of the Civil War. During most of the 19th century, Spain was a constitutional monarchy, but under attack from these various directions. The First Spanish Republic, founded in 1873, was shortlived. A monarchy under Alfonso XIII lasted from 1887 to 1931, but from 1923 was held in place by the military dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera. Following Primo de Riveras overthrow in 1930, the monarchy was unable to maintain power and the Second Republic was declared in 1931. This Republic soon came to be led by a coalition of the left and center. A number of controversial reforms were passed, such as the Agrarian Law of 1932, distributing land among poor peasants. Millions of Spaniards had been living in more or less absolute poverty under the firm control of the aristocratic landowners in a quasi-feudal system. These reforms, along with anticlericalist acts, as well as military cut-backs and reforms, created strong opposition.

Constitution of 1931

Spanish Constitution of 1931

The neutrality of this article is disputed.

A new constitution was adopted on 9 December 1931. The document generally accorded thorough civil liberties and representation, the notable exclusion being the rights of Catholics, a flaw which prevented the forming of an expansive democratic majority. The document provided for universal suffrage and proclaimed a purported complete separation of Church and State, but in actuality it provided for significant governmental interference in church matters, including the prohibition of teaching by religious even in private schools, confiscation of and prohibitions on ownership of church property, and the banning of the Society of Jesus. The revolution of 1931 essentially established an anticlerical government.

Not only advocates of establishment of religion but also advocates of church/state separation saw the constitution as hostile; one such advocate of separation, Jose Ortega y Gasset, stated the article in which the Constitution legislates the actions of the Church seems highly improper to me. On June 3, 1933, Pope Pius XI condemned the Spanish Governments deprivation of the civil liberties on which the Republic was supposedly based in the encyclical Dilectissima Nobis (On Oppression Of The Church Of Spain ), noting in particular the expropriation of Church property and schools and the persecution of religious communities and orders.

Since the far left considered moderation of the anticlericalist aspects of the constitution as totally unacceptable, commentators have argued that the Republic as a democratic constitutional regime was doomed from the outset. Commentators have posited that such a hostile approach to the issues of church and state were a substantial cause of the breakdown of democracy and the onset of civil war.

1933 election and aftermath

Leading up to the Civil War, the state of the political establishment had been brutal and violent for some time. In the 1933 elections to the Cortes Generales, the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (Confederacion Espanola de Derechas Autonomas or CEDA) won a plurality of seats. It was however not enough to form a majority. Despite the results, then President Niceto Alcala-Zamora declined to invite the leader of the CEDA to form a government and instead invited the Radical Republican Party and its leader Alejandro Lerroux to do so. CEDA supported the Lerroux government; it later demanded and, on 1 October 1934, received three ministerial positions. Hostility between both the left and the right increased after the formation of the Government. Spain experienced general strikes and street conflicts. Noted among the strikes was the miners revolt in northern Spain and riots in Madrid. Nearly all rebellions were crushed by the Government and political arrests followed.

Lerrouxs alliance with the right, his harsh suppression of the revolt in 1934, and the Stra-Perlo scandal combined to leave him and his party with little support going into the 1936 election. (Lerroux himself lost his seat in parliament.)

1936 Popular Front victory and aftermath

In the 1936 Elections a new coalition of Socialists (Socialist Workers Party of Spain, PSOE), liberals (Republican Left and the Republican Union Party), Communists, and various regional nationalist groups won the extremely tight election. The results gave 34 percent of the popular vote to the Popular Front and 33 percent to the incumbent government of the CEDA. This result, when coupled with the Socialists refusal to participate in the new government, led to a general fear of revolution. This was made only more apparent when Largo Caballero, hailed as the Spanish Lenin by Pravda, announced that the country was on the cusp of revolution. However these statements were meant only to remove any moderates from his coalition. Moderate Socialist Indalecio Prieto condemned the rhetoric and marches as provocative.

Aims of the Popular Front

From the Cominterns point of view the increasingly powerful, if fragmented, left and the weak right were an optimum situation. Their goal was to use a veil of legitimate democratic institutions to outlaw the right and to convert the state into the Soviet vision of a peoples republic with total leftist domination, a goal which was repeatedly voiced not only in Comintern instructions but also in the public statements of the PCE (Communist Party of Spain).

Azana becomes president

Without the Socialists, Prime Minister Manuel Azana, a liberal who favored gradual reform while respecting the democratic process, led a minority government. In April, parliament replaced President Niceto Alcala-Zamora, a moderate who had alienated virtually all the parties, with Azana. The removal of Zamora was made on specious grounds and in violation of the constitution. Although the right also voted for Zamoras removal, this was a watershed event which inspired many conservatives to give up on parliamentary politics. Azana was the object of intense hatred by Spanish rightists, who remembered how he had pushed a reform agenda through a recalcitrant parliament in 1931-33. Joaquin Arraras, a friend of Francisco Franco, called him a repulsive caterpillar of red Spain. The Spanish generals particularly disliked Azana because he had cut the armys budget and closed the military academy while war minister (1931). CEDA turned its campaign chest over to army plotter Emilio Mola. Monarchist Jose Calvo Sotelo replaced CEDAs Gil Robles as the rights leading spokesman in parliament.

Rising tensions and political violence

This was a period of rising tensions. Radicals became more aggressive, while conservatives turned to paramilitary and vigilante actions. According to official sources, 330 people were assassinated and 1,511 were wounded in politically-related violence; records show 213 failed assassination attempts, 113 general strikes, and the destruction (typically by arson) of 160 religious buildings.

Deaths of Castillo and Calvo Sotelo

On 12 July 1936, in Madrid, a far right group murdered Lieutenant Jose Castillo of the Assault Guards, a special police corps created to deal with urban violence, and a Socialist. The next day, leftist gunman Luis Cuenca killed Jose Calvo Sotelo, a leader of the conservative opposition in the Cortes (Spanish parliament), in revenge. Cuenca was operating in a commando unit of the Assault Guard led by Captain Fernando Condes Romero. Condes was close to the Socialist leader Indalecio Prieto, but there is no indication that Prieto was complicit in Cuencas assassination of Calvo Sotelo. However, the murder of such a prominent member of parliament, with involvement of the police, aroused suspicions and strong reactions amongst the Center and the Right. Calvo Sotelo was the leading Spanish monarchist. He protested against what he viewed as escalating anti-religious terror, expropriations, and hasty agricultural reforms, which he considered Bolshevist and anarchist. He instead advocated the creation of a corporative state and declared that if such a state was fascist, he was also a fascist.

He also declared that Spanish soldiers would be mad to not rise for Spain against Anarchy. In turn, the leader of the communists, Dolores Ibarruri, known as La Pasionaria, allegedly vowed that Calvo Sotelos speech would be his last speech in the Cortes. Although the Nationalist generals were already at advanced stages of planning an uprising, the even provided a convenient catalyst and public justification for their planned coup.

Spain Divides[1]

The initial division of forces and resources was unsatisfactory to both Republicans and rebels. The rebels lost their leader, General Sanjurjo, in a plane crash as he set off from Portugal on 20 July 1936 to take command in Burgos. They held Spanish Morocco, where Franco had reached Tetuán on the 19th, after the rising had already succeeded. Franco therefore had the Army of Africa at his command, and a small detachment of the air force, which had attempted resistance but been overwhelmed. But he faced the problem of how to get his formidable forces to the mainland, since the crews on board Spanish ships in the Mediterranean disobeyed their rebel naval officers, executed them and remained loyal to the Republic. Cádiz, held by the rebel generals Varela and Lopez Pinto, could not be reached. Beyond it, Queipo de Llano took Seville, including the airport. This permitted a group of the Foreign Legion to fly there from Morocco in a Fokker, and take part in the merciless assault on the working-class district of Triana. But the rest of the forces in north Africa were stuck.

The rising also triumphed in the agrarian conservative heartlands of Old Castile, Navarre and the far north-west, including the naval base of El Ferrol. But it failed along most of the north coast, including Bilbao with its all-important iron and steel works, and across a great swathe of central, eastern and north-eastern Spain, including Madrid, and the great industrial city of Barcelona. Not only was north Africa cut off from southern Spain by Republican ships, but western Andalusia was cut off from rebel territory in the north. It was impossible for anyone to exercise overall command. Moreover, army officers were not the undisputed leaders everywhere of the rebellion.

In Navarre General Mola was well aware of the strength of the Carlist militias. Elsewhere, Falangist militias or monarchist activists operated independently, and in many towns where there was no military garrison, they led the rising. Meanwhile the Falange leader, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, was in a Republican prison far away in Alicante.

On the government side, it was depressing enough that within just a few days about a third of the country was in the hands of its enemies. But the military rebellion sparked a furious popular reaction that stripped the government, and the Republican state, of authority. Everywhere trade unionists and left-wing parties demanded that arms be distributed to them. Prime Minister Casares Quiroga resisted these demands on 18 July, then resigned. President Azaña appointed Diego Martinez Barrio in his place, who tried futilely to win over General Mola, then also resigned early on the 19th.

The new Prime Minister was José Giral, who took the inevitable step of arming the Madrid proletariat by supplying the Socialist and Anarchist trade unions with army rifles. When the Madrid garrisons were ordered to hand over the bolts that the rifles needed, they refused. General Fanjul, leader of the rebellion in Madrid, was trapped in the Montana barracks by crowds of hostile workers, some of them now armed. Giral's decision to arm left-wing organisations was also implemented elsewhere. Power seeped away from the government to the streets, and from the institutions of the state to the revolutionary masses.

On 20 July the Montana barracks were attacked by the crowds, aided by a few aircraft, some artillery, and loyal Assault Guards and Civil Guards. Fanjul's forces, numbering about 2,000, with about 150 additional right-wing sympathisers, replied with machine-guns. But at noon the assault succeeded, and crowds surged into the courtyard of the barracks, fighting hand to hand with its defenders. Several hundred people died. Fanjul was imprisoned, and in the following month court-martialled and shot. The other Madrid garrisons were either persuaded into loyalty or overwhelmed. Events in Barcelona were similar, except that the rebel plan there was for the troops of the various garrisons, about 5,000 men in all, to converge on the Plaza de Catalunya in the centre, and then take the city. The President of the autonomous government of Catalonia, Luis Companys, had refused to distribute arms to the masses, just as Casares Quiroga and Martinez Barrio had done. But he could not prevent some Guards doing so independently. Approximately 5,000 loyal Assault and Civil Guards, some police and crowds of Anarchists, a few of them now armed, fought bravely with the columns of infantrymen making their way to the Plaza de Catalunya. They prevented the planned meeting there, and took control of the city, completing it with an attack on the AtarAzañas barracks on the night of 20-21 July. At least 500 people died in the confrontation in Barcelona. General Goded was taken prisoner, and in August was tried for military rebellion and shot. Local air bases remained loyal.

In several other places, the outcome of the rising was in doubt in the first days. In Oviedo, centre of the October 1934 revolution, the local military commander, Colonel Antonio Aranda, assured miners' leaders that the city was safe in his hands. After they set off by train to help defend Madrid on 19 July, he claimed the city for the rebels. His actions produced the extraordinary phenomenon of a city thoroughly identified with revolutionary fervour falling without a fight into the camp of counter-revolution. But Oviedo was isolated in hostile Republican territory.

At the other end of the country, Granada was similarly isolated, a rebel city in the middle of an anti-rebel area, after the military commander, General Muñoz, was imprisoned by rebel officers, and the working-class quarter violently subdued. In many cities, the issue was decided by the personal decision for or against the rising made by the commanding officer, as was the case in Badajoz, with General Luis Castelló (for the government), and Cordoba, with Colonel Ciriaco Cascajo (for the rebels). Sometimes, however, the commanding officer discovered that no one was following him. General José Bosch was prevented by his own troops from taking Minorca for the rebels, even though in Majorca and Ibiza they had triumphed.

Whether the rebels had to fight to gain control, or triumphed easily, their success was followed by the immediate, violent repression of those identified with the Popular Front. Members of the left-wing parties, trade unionists and freemasons were killed by rebel soldiers, Civil Guards, Carlists and Falangists, acting either on direct orders from the military commanding officer, or on their own initiative. Sometimes there was a summary trial, often not. Even where the rebels were obviously in complete control locally, such as in Navarre, rightist gangs summarily arrested political opponents, drove them out of the town or village, and shot them by the roadside. This terror was to intimidate, control and punish.

By 20 July it was obvious that, where the rising failed, the government nonetheless was not the victor. Anarchists, Socialists and Communists ruled the streets, setting up anti-fascist, revolutionary committees. As Luis Companys, President of the Catalan regional government, acknowledged to Anarchist leaders in Barcelona, 'Today, you are the masters of the city.' Except in the Republican Basque provinces of Vizcaya and Guipúzcoa, where the moderate Basque Nationalist party (PNV) dominated, revolutionary terror was directed against propertied elites, conservative politicians and the church. Except in the Basque country, Catholicism went underground in Republican Spain, as churches burned and religious images were destroyed.

The violence on both sides was sickening, sharpened by the class hatreds and cultural conflicts that had marked Spanish history for decades. The army officers who took up arms against the Republic in July 1936 bore the immediate responsibility for unleashing the whirlwind of violence. They argued, however, that the violence began not in July 1936, but in the revolution of October 1934, and that the Popular Front was the illegitimate continuation of the forces which made that revolution. This controversial claim was used in July 1936, and continuously thereafter, even when the war was over, to justify repression, reprisals and summary justice.

After the patchy fortunes of the coup, and after the first days of fighting, about 13 million Spaniards found themselves still in Republican Spain, which also contained almost all major industry and the financial reserves of the Bank of Spain. About 11 million were in territory taken by the rebels, now arrogating to themselves the title of 'nationals', or Nationalists. This territory at least had the advantage of including some of Spain's most productive wheat-growing areas.

The Spanish army on the mainland and in the Balearic and Canary Islands numbered something over 60,000 men at the time of the coup. It was organised into eight territorial divisions on the mainland, one in the Canary Islands and another in the Balearic Islands. Each of the mainland divisions had two infantry brigades, one artillery brigade and support units. Just over half were in Republican territory, the rest in Nationalist. In addition, the Army of Africa in rebel-held Morocco numbered about 25,000. It comprised five infantry battalions, six Foreign Legion banderas or battalions, 30 tabores or half-battalions of indigenous Moroccan Regulars, plus artillery, cavalry and engineers.

The Foreign Legion was the creation of José Millán Astray, a crazed militarist, and was renowned for its ruthless daring. It was a last resort for desperate men. Later in the war, Millán Astray caused a commotion when he shouted 'Death to intelligence' and the Legion's blood-curdling slogan 'Long live death' at Spain's most revered philosopher, Miguel Unamuno, in Salamanca University. It was one of the most bizarre cultural confrontations of the war.

There were also about 80,000 men serving in the militarised law enforcement organisations - approximately 34,000 Civil Guards, over 31,000 Assault Guards and nearly 15,000 carabineers. The majority remained with the Republic - about 20,000 Civil Guards, 22,000 Assault Guards and 9,000 carabineers. On paper, therefore, the two sides seemed to have roughly equal numerical strength, with the Republic's advantage in the militarised security forces roughly balancing the Nationalists' control of the Army of Africa. Rifles, bayonets and artillery pieces were split between the two sides, although many of the rifles were pre-1914 issue, and ammunition was often in short supply.

Both sides needed to recruit and train soldiers swiftly, and both began enlisting men as soon as possible. Both sides set up very abbreviated officers' training courses, and the Nationalists used non-commissioned as well as commissioned officers. On both sides, men complained about lack of training, lack of ammunition, and old, poorly functioning equipment. But the impression of balance is misleading. Many of the conscripts on Republican territory simply left their posts in the confusion and melted away, while only a minority of officers were considered reliable. Moreover, the forces in north Africa were trained, disciplined and experienced, in stark contrast to the situation of many soldiers in mainland garrisons. The Spanish air force was small. In late July 1936, the government had about 200 planes and the Nationalists about 100 - in both cases a mixture of reconnaissance planes (mainly Breguet XIX), fighters (mainly Nieuports) and bombers (a mixture of Fokker VIIs, De Havilland Dragons and Douglas DC2s). The government could count on a battleship, three cruisers, 20 destroyers and 12 submarines, but the commanding officers of many of these had been killed by mutinous crews, who were loyal but lacked expertise. The Nationalists fared less well, with one battleship, two cruisers, one destroyer and two submarines. Moreover, the government had over two-thirds of the merchant shipping.

Where new production was concerned, the Republic controlled the major arms factories, and the Nationalists the major naval dockyard at El Ferrol. All in all, considering territory, population, financial resources, industry, agriculture and armaments, the government looked better supplied for a long struggle, but had to rebuild its army, and translate the enthusiasm of the popular militias based on the left-wing parties and trade unions into military effectiveness. The rebels lacked industrial strength, but had greater military control of their (divided) territory.

In these circumstances, in which neither side was assured of victory and both urgently needed arms, it was inevitable that both would look beyond Spain for foreign assistance. Within days of its outbreak, the Spanish Civil War would become an international problem.

Outbreak of the war

Nationalist military revolt

On 17 July 1936, the nationalist-traditionalist rebellion long feared by some in the Popular Front government began. Its beginning was signaled by the phrase Over all of Spain, the sky is clear that was broadcast on the radio. Casares Quiroga, who had succeeded Azana as prime minister, had in the previous weeks exiled the military officers suspected of conspiracy against the Republic, including Puerto Rico-born General Manuel Goded Llopis and General Francisco Franco, sent to the Balearic Islands and to the Canary Islands, respectively. Both generals immediately took control of these islands. A British MI6 intelligence agent, Major Hugh Pollard, then flew Franco to Spanish Morocco in a de Havilland DH.89 Dragon Rapide to see Juan March Ordinas, where the Spanish Army of Africa, led by Nationalist ranks, were almost unopposed in assuming control.

Government reaction

The rising was intended to be a swift coup detat, but was botched in certain areas allowing the government to retain control of parts of the country. At this first stage, the rebels failed to take any major cities - in Madrid they were hemmed into the Montana barracks. The barracks fell the next day with much bloodshed. In Barcelona, anarchists armed themselves and defeated the rebels. General Goded, who arrived from the Balearic islands, was captured and later executed. However, the turmoil facilitated anarchist control over Barcelona and much of the surrounding Aragonese and Catalan countryside, effectively breaking away from the Republican government. The Republicans held on to Valencia and controlled almost all of the Eastern Spanish coast and central area around Madrid. Except for Asturias, Cantabria and part of the Basque Country, the Nationals took most of northern and northwestern Spain and also a southern area in central and western Andalusia including Seville.

The combatants

The Republicans

Republicans (also known as Spanish loyalists) received weapons and volunteers from the Soviet Union, Mexico, the international Socialist movement and the International Brigades. The Republicans ranged from centrists who supported a moderately capitalist liberal democracy to revolutionary anarchists and communists; their power base was primarily secular and urban, but also included landless peasants, and it was particularly strong in industrial regions like Asturias and Catalonia. This faction was called variously the loyalists by its supporters, the Republicans, the Popular Front or the Government by all parties, and the reds by its enemies.

The conservative, strongly Catholic Basque country, along with Galicia and the more left-leaning Catalonia, sought autonomy or even independence from the central government of Madrid. This option was left open by the Republican government. All these forces were gathered under the Ejercito Popular Republicano (EPR) or Republican Popular Army.

Scholar Stanley G. Payne claimed that by the time of the outbreak of war Republicans had abandoned constitutional republicanism for leftist revolution:

The leftist zone has been variously designated Republican, loyalist, and Popular Front. Of those terms, the adjective loyalist is somewhat misleading, for there was no attempt to remain loyal to the constitutional Republican regime. If that had been the scrupulous policy of the left, there would have been no revolt and civil war in the first place. Thus after July 1936 what remained of the constitutional Republic gave way to the revolutionary Republican confederation of 1936-1937.

The Nationalists

The Nationalists on the contrary opposed the separatist movements, but were chiefly defined by their anti-communism and their fear of Spain breaking up, which served as the galvanizing agent of diverse or even opposed movements like falangists or monarchists. This side was called the Nationalists, the rebels, or the insurgents. Their opponents referred to them as the Fascists or Francoists.

Their leaders had a generally wealthier, more conservative, monarchist, landowning background, and they favoured the centralization of state power. In turn, their support for the Catholic Church, provided them with popular support.Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, as well as most Roman Catholic clergy, supported the Nationalists, while Portugals Estado Novo provided logistical support. Their forces were gathered into the Ejercito Nacional or National Army.

Other factions in the war

The active participants in the war covered the entire gamut of the political positions and ideologies of the time. The Nationalist (nacionales) side included the Carlists and Legitimist monarchists, Spanish nationalists, the Falange, Catholics, and most conservatives and monarchist liberals. On the Republican side were socialists, communists, liberals and anarchists. Catalan and Basque nationalists were not univocal. Left-wing Catalan nationalists were on the Republican side. Conservative Catalan nationalists were far less vocal supporting the Republican government due to the anti-clericalism and confiscations occurring in some areas controlled by the latter (some conservative Catalan nationalists like Francesc Cambo actually funded the rebel side). Basque nationalists, heralded by the conservative Basque nationalist party, were mildly supportive of the Republican government, even though Basque nationalists in Alava and Navarre sided with the uprising for the same reasons influencing Catalan conservative nationalists.

To view the political alignments from another perspective, the Nationals included the majority of the Catholic clergy and of practicing Catholics (outside of the Basque region), important elements of the army, most of the large landowners, and many businessmen. The Republicans included most urban workers, most peasants, and much of the educated middle class, especially those who were not entrepreneurs.

The genial monarchist General Jose Sanjurjo was the figurehead of the rebellion, while Emilio Mola was chief planner and second in command. Mola began serious planning in the spring, but General Francisco Franco hesitated until early July, inspiring other plotters to refer to him as Miss Canary Islands 1936. Franco was a key player because of his prestige as a former director of the military academy and the man who suppressed the Socialist uprising of 1934. Warned that a military coup was imminent, leftists put barricades up on the roads on July 17. Franco avoided capture by taking a tugboat to the airport. From there he was flown to Morocco by British intelligence, where he took command of the battle-hardened colonial army in Spanish Morocco. Sanjurjo was killed in a plane crash on July 20, leaving effective command split between Mola in the north and Franco in the South. Franco was chosen overall commander at a meeting of ranking generals at Salamanca on September 21. He outranked Mola and by this point his Army of Africa had demonstrated its military superiority.

One of the Nationalists principal claimed motives was to confront the anti-clericalism of the Republican regime and to defend the Roman Catholic Church, which had been the target of attacks, and which many on the Republican side blamed for the ills of the country. Even before the war religious buildings were burnt and clergy killed without action on the part of the Republican authorities to prevent it. As part of the social revolution taking place, others were turned into Houses of the People. Similarly, many of the massacres perpetrated by the Republican side targeted the Catholic clergy. Francos Moroccan Muslim troops found this repulsive as well, and for the most part fought loyally and often ferociously for the Nationalists. Articles 24 and 26 of the Constitution of the Republic had banned the Jesuits, which deeply offended many within the conservatives. The revolution in the republican zone at the outset of the war, killing 7,000 clergy and thousands of lay people, constituted what Stanley Payne called the most extensive and violent persecution of Catholicism in Western History, in some way even more intense than that of the French Revolution, driving Catholics, left then with little alternative, to the Nationalists even more than would have been expected. After the beginning of the Nationalist coup, anger flared anew at the Church and its role in Spanish politics. Notwithstanding these religious matters, the Basque nationalists, who nearly all sided with the Republic, were, for the most part, practicing Catholics.

Republican sympathizers proclaimed it as a struggle between tyranny and democracy, or fascism and liberty, and many non-Spanish youth, committed reformers and revolutionaries joined the International Brigades, believing that the Spanish Republic was the front line of the war against fascism. Francos supporters, however, portrayed it as a battle between the red hordes of communism and anarchism on the one hand and Christian civilization on the other. They also stated that they were protecting the Establishment and bringing security and direction to what they felt was an ungoverned and lawless society.

The Republicans were also split among themselves. The left and Basque or Catalan nationalist conservatives had many conflicting ideas. The Cortes (Spanish Parliament) consisted of 16 parties in 1931. When autonomy was granted to Catalonia and the Basque Provinces in 1932, a nationalist coup was attempted but failed. An attempt by the communists to seize control resisted by anarchists resulted in the massacre of hundreds of rebels and intra civil war between anarchists and communists in Catalonia.

Foreign involvement

The Spanish Civil War had large numbers of non-Spanish citizens participating in combat and advisory positions. Foreign governments contributed large amounts of financial assistance and military aid to forces led by Generalisimo Francisco Franco. Forces fighting on behalf of the Second Spanish Republic also received limited aid but support was seriously hampered by the arms embargo declared by France and the UK.

These embargoes were never extremely effective however, and France especially was accused of allowing large shipments through to the Republicans - though the accusations often came from Italy, itself heavily involved for the Nationalists. The clandestine actions of the various European powers were at the time considered to be risking another Great War.

Italy and Germany

Both Fascist Italy, under dictator Benito Mussolini, and Nazi Germany, under dictator Adolf Hitler, sent troops, aircraft, tanks, and other weapons to support Franco. The Italian government provided the Corps of Volunteer Troops (Corpo Truppe Volontarie) and Germany sent the Condor Legion (Legion Condor). The CTV reached a high of about 50,000 men and as many as 75,000 Italians fought in Spain. The German force numbered about 12,000 men at its zenith and as many as 19,000 Germans fought in Spain.

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union primarily provided material assistance to the Republican forces. While Soviet troops amounted to no more than 700 men, Soviet volunteers often piloted aircraft or operated tanks purchased by the Spanish Republican forces. The Republic had to purchase Soviet assistance with the official gold reserves of the Bank of Spain (see Moscow Gold), obtaining armament of marginal quality that, in addition, was sold at deliberately inflated prices. The cost for the Republic of the Soviet support raised more than US$500 million, which made up two-thirds of the gold reserves that Spain had at the beginning of the war.

International brigade volunteers

The troops of the International Brigades represented the largest foreign contingent of troops fighting for the Republicans. Roughly 30,000 foreign nationals from possibly up to 53 nations fought in the various brigades. Most of them were communists or trade unionists, and while organised by communists guided or controlled by Moscow, they were almost all individual volunteers.

Mexico

The Mexican Republic supported fully and publicly the claim of the Madrid government. Mexico refused to follow the French-British Non-Intervention proposals, recognizing immediately the great advantage they offered the Insurgents. Contrary to the United States, Mexico did not feel that neutrality between an elected government and a military junta was a proper policy. Mexicos attitude gave immense moral comfort to the Republic, especially since the major Latin American governments - those of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Peru - sympathized more or less openly with the Insurgents. But Mexican aid could mean relatively little in practical terms if the French border were closed and if the dictators remained free to supply the Insurgents with a quality and quantity of weapons far beyond the power of Mexico.

However, Mexico provided some material assistance, which included a small amount of American made aircraft such as the Bellanca CH-300 and Spartan Zeus that served in the Mexican Air Force.

Irish volunteers

Ireland was the only country where pro-Franco volunteers outnumbered the anti-Franco volunteers. Despite the declaration by the Irish government that participation in the war was illegal, around 250 Irishmen went to fight for the Republicans and around 700 of Eoin ODuffys followers ( The Blueshirts ) went to Spain to fight on Francos side.

On arrival, however, O'Duffys Irish contingent refused to fight the Basques for Franco, seeing parallels between their recent struggle and Basque aspirations. They saw their primary role in Spain as fighting communism, rather than defending Spains territorial integrity. Eoin O'Duffys men saw little fighting in Spain and were sent home by Franco after being accidentally fired on by Spanish Nationalist troops.

Evacuation of children

As war proceeded in the Northern front, the Republican authorities arranged the evacuation of children. These Spanish War children were shipped to Britain, Belgium, the Soviet Union, other European countries and Mexico. Those in Western European countries returned to their families after the war, but many of those in the Soviet Union, from Communist families, remained and experienced the Second World War and its effects on the Soviet Union.

Like the Republican side, the Nationalist side of Franco also arranged evacuations of children, women and elderly from war zones. Refugee camps for those civilians evacuated by the Nationalists were set up in Portugal, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium.

Pacifism in Spain

In the 1930s Spain also became a focus for pacifist organizations including the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the War Resisters League and the War Resisters International (whose president was the British MP and Labour Party leader George Lansbury). Many people including, as they are now called, the insumisos (defiant ones, i.e., conscientious objectors) argued and worked for non-violent strategies.

Prominent Spanish pacifists such as Amparo Poch y Gascon and Jose Brocca supported the Republicans. As American author Scott H. Bennett has demonstrated, pacifism in Spain certainly did not equate with passivism, and the dangerous work undertaken and sacrifices made by pacifist leaders and activists such as Poch and Brocca show that pacifist courage is no less heroic than the military kind (Bennett, 2003: 67-68). Brocca argued that Spanish pacifists had no alternative but to make a stand against fascism. He put this stand into practice by various means including organising agricultural workers to maintain food supplies and through humanitarian work with war refugees.

Atrocities during the war

At least 50,000 people were executed during the civil war. In his recent, updated history of the Spanish Civil War, Antony Beevor reckons Francos ensuing white terror claimed 200,000 lives. The red terror had already killed 38,000. Julius Ruiz concludes that although the figures remain disputed, a minimum of 37,843 executions were carried out in the Republican zone with a maximum of 150,000 executions (including 50,000 after the war) in Nationalist Spain.

The atrocities of the Bando Nacional were common and were frequently ordered by authorities in order to eradicate any trace of leftism in Spain; many such acts were committed by reactionary groups during the first weeks of the war. This included the execution of school teachers (because the efforts of the Republic to promote laicism and to displace the Church from the education system by closing religious schools were considered by the Bando Nacional side as an attack on the Church); the execution of individuals because of accusations of anti-clericalism; the massive killings of civilians in the cities they captured; the execution of unwanted individuals (including non-combatants such as trade-unionists and known Republican sympathisers etc) An example of this kind of tactics on the Nationalist side was the Massacre of Badajoz in 1936.

The Nationalist side also conducted aerial bombing of cities in the Republican territory, carried out mainly by the Luftwaffe volunteers of the Condor Legion and the Italian air force volunteers of the Corpo Truppe Volontarie (Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Guernica, and other cities). The most notorious example of this tactic of terror bombings was the Bombing of Guernica.

Atrocities by the Republicans have been termed Spains red terror by those on the Nationalist side. Republican attacks on the Catholic Church, associated strongly with support for the old monarchist and hierarchical establishment, were particularly controversial.

Nearly 7,000 clerics were killed and churches, convents and monasteries were attacked (see Martyrs of the Spanish Civil War). Some 13 bishops, 4184 diocesan priests, 2365 male religious (among them 114 Jesuits) and 283 nuns were killed. There are unverified accounts of Catholics being forced to swallow rosary beads and/or being thrown down mine shafts, as well as priests being forced to dig their own graves before being buried alive. Pope John Paul II beatified several hundred people murdered for being priests or nuns, and Pope Benedict XVI beatified almost 500 more on October 28, 2007.

Other repressive actions in the Republican side were committed by specific factions such as the Stalinist NKVD (the Soviet secret police). In addition, many Republican politicians, such as Lluis Companys the Catalan nationalist president of the Generalitat de Catalunya, the autonomous government of Catalonia -which remained initially loyal to the Republic before proclaiming independence from it- carried out numerous actions to mediate in cases of deliberate executions of the clergy.

Two Spains[1]

As the Spanish Civil War progressed, it soon became clear that Republican Spain and Nationalist Spain were two different states, and even different worlds. The Republic remained under civilian government, which struggled to assert its authority. At first, it was powerless to restrain the social revolution that swept through the country when the war began. Then Largo Caballero's government of September 1936 to May 1937 had some success in containing the revolution, by bringing the Anarchists into government, subduing the revolutionary terror and building a new army that absorbed the popular militias.

His successor, Juan Negrín, backed by the Soviet Union and the Spanish Communists, went further and dismantled the revolution - ending the collectives, restoring private property and imposing political and military discipline in an all-out effort to concentrate resources on the military objective of fighting the war. But throughout the war, competing political parties and trade unions continued. Moreover, central government co-existed with autonomous regional governments.

A Basque government exercised local power from September 1936 until the fall of Vizcaya in June 1937, and the Catalan Generalitat right up to the fall of Barcelona in January 1939. The Council of Aragón also claimed a quasi-governmental status until its dissolution by the central government in August 1937.

Nor was the government's authority helped by the fact that it moved twice under the pressure of Nationalist onslaughts. In November 1936 it abandoned Madrid for Valencia, and at the end of October 1937 it left Valencia for Barcelona, where relations with the Catalan government became particularly difficult. After the fall of Barcelona in January 1939, the Republic had no proper seat of government at all. But even at the height of Negrín's efforts, power was never fully centralised, and the pervasive influence of Soviet and Comintern advisers and the Communist Party was never fully accepted. The contrast on the Nationalist side could hardly have been greater. Although political parties, notably the Falange and the Carlists, mobilised militias and other support, the dominance of the military was always obvious. It was generals who planned and led the rising against the Republic. In the summer of 1936, Mola controlled Nationalist territory in northern Spain, Queipo de Llano controlled Seville, and Franco controlled north Africa and the ever-expanding areas of southern Spain conquered by his campaign.

Mola declared martial law - somewhat theoretically - over the whole country on 28 July 1936, and it was imposed in fact, wherever the Nationalists triumphed. The first, rudimentary administration was set up in Burgos on 24 July by Mola, with General Cabanellas at its head. Franco was appointed head of government as well as Commander-in-chief by his fellow generals at Burgos on 1 October 1936, and took to himself the title of head of state. He appointed a new provisional government on 2 October, and Burgos remained the centre of many government departments throughout the war, though some were located in Salamanca, where Franco established his military headquarters.

In April 1937 he consolidated power further by unilaterally merging all political organisations in Nationalist Spain into one mass party. There could be no doubt that politics were subordinated to military needs, and Nationalist Spain was Franco Spain. Whether Franco's Spain was fascist is more debatable. It adopted the fascist salute, but the traditional, red-and-gold monarchist flag. It was a one-party state, but that one party greatly disappointed the camisas viejas, the 'old shirts' of the earlier, radical stage of the Spanish Falange, as it became virtually an agency of the administration. Some fascist policies were borrowed directly from Mussolini's Italy, most obviously the Labour Charter of March 1938. A bureaucratic, vertical trade union was established, while all others were abolished.

In foreign policy, the early regime's sympathies were quite obviously with its backers, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. But in contrast to Hitler and Mussolini, the foundation of Franco's power lay in military victory, not mass mobilisation; unlike them he was first and foremost a soldier, and his own values remained those of the Spanish anti-democratic, military tradition. Furthermore, his regime handed to the Catholic Church a degree of control over education, culture, public morality, public spectacle and censorship that was unthinkable in Nazi Germany, and which even in Italy the church was struggling unsuccessfully to retain in the 1930s.[1]

Daily life

Daily life as well as politics was very different in the two zones. On the Republican side, the first euphoria of social revolution in 1936 included the collectivisation of farms, especially in Aragón and Catalonia, and of industries and businesses, most notably in Barcelona. Workers took control, and the bourgeoisie seemed to disappear as proletarian forms of dress became the only safe ones apart from military uniform.

Capitalism vanished. In some rural collectives, money itself was abolished. It has always been hard to determine how successful the collectives were. They did not last long enough to provide much reliable evidence, since they were dismantled under government pressure after Largo Caballero's fall in May 1937. Moreover, the industrial collectives had to switch production to war needs, which made comparisons with previous output problematic.

In agriculture, many peasants distrusted collectivism and would have much preferred the redistribution of land in individual plots. What is certain is that collectivisation made central co-ordination of war and other production extremely difficult. In the Republican economy as well as in politics, the dominant pattern in the first stages of the war was fragmentation.

As the war continued, and especially after Negrín became Prime Minister in May 1937, economic organisation lost its revolutionary features. But daily life was more and more dominated by the consequences of the Republic's military failures. As territory and with it the available population diminished, men were called up at ever-widening age extremes - eventually from 17-year-olds to 55-year-olds. Food supplies inevitably diminished. Queues for food became an inescapable feature of the war, and a black market with high prices developed. The population of Madrid had a particularly grim time. Not only had it somehow to endure siege and bombardment from November 1936 onwards, but over the last year of the war it also had to manage on a very meagre and inadequate diet. Rations of lentils became known resignedly as 'Dr Negrín's pills'.

By contrast, from the beginning the Nationalists held most of the great wheatlands of Old Castile, and as territorial dominance increased, a range of food including eggs, meat, oil, vegetables and rice was steadily available. Price controls were imposed on many basic foods, including wheat and sugar beet. Economic stability was aided by loans to the Nationalists - who had no gold reserves to fall back on - by sympathetic Spanish financiers, of whom the most important was the Catalan Juan March. Equally important was the willingness of big international companies like Texaco and Firestone to sell crucial commodities such as oil and rubber to the Franco regime on credit.

These arrangements, together with the systems agreed with Hitler and Mussolini for armaments, enabled the Nationalists to prosecute the war and take on the huge debts it entailed, amounting to about 700 million dollars by the end of the war, without having to tax the civilian population excessively. The Franco regime also confiscated the property of those it deemed politically responsible for provoking the rising of July 1936, or of sustaining the Republic after that date, a procedure governed by the notorious Law of Political Responsibilities of 9 February 1939. Thus history was rewritten, the rebels became the legitimate government, and the erstwhile legitimate political authorities of the Second Republic became rebels.

Nationalist Spain resounded with martial music, patriotic parades and Catholic hymns. It was always likely that the Catholic Church would be more sympathetic to a military regime of order and traditional values than to the secularising and modernising Republic. Many Catholics were deeply opposed to the Republic well before 1936. But for most of those whose minds were not already made up, the question of loyalties was settled irrevocably by the murderous anti-clericalism of the social revolution in the summer of 1936, in areas where the military rising failed. One side protected religion, the other attacked it and drove it underground. Churches were destroyed, religious symbols and statues defaced and smashed.

Almost inevitably in these circumstances, Nationalist Spain took on the mantle of a religious crusade. Priests blessed weapons, prayed that battles would go the right way and celebrated victory with religious services. In a famous joint letter of July 1937, the Spanish bishops argued that the war was a confrontation between Christian civilisation and atheistic Communism, and urged bishops all over the world to explain this to the faithful. Pope Pius XII could hardly avoid greeting Franco's ultimate victory with 'immense joy', in a radio broadcast in April 1939. A few church leaders had important reservations about the wisdom of siding so fully with one band against another in a civil conflict. Some prominent Catholic laymen pointed out that the violence against priests and religion had been the policy of the revolutionary mobs, not the Republic itself. But the die was cast. Franco's Spain was Catholic Spain.

Women

The Nationalists were also traditionalists where gender roles in society were concerned. The Republic, on the other hand, represented change. One of the most famous Republican posters carried the slogan 'They shall not pass', which the great Communist leader and orator Dolores Ibárruri (La Pasioiniria) had made into the rallying-call for the defence of the Republic, and especially of Madrid. Above this armed soldiers, one of them a woman, wearing the blue overalls that were the improvised uniform of the Republican militias in the early stages of the war, fired at their enemies. Women soldiers and La Pasionaria became dominant images of the Republic at war.

Women in unisex workers' overalls symbolised a new world, in which women and men could be equal. Women could be politicians, public speakers, even soldiers, the most traditionally masculine of all occupations. As it happens, the first British casualty of the civil war, the sculptor Felicia Browne, was killed in action in a Republican militia near Saragossa on 25 August 1936.

Behind the lines, too, great changes occurred. The Second Republic had seen the entry of women into politics, as parliamentary deputies, voters and activists. Now the first female government minister was appointed, Federica Montseny, Anarchist Minister of Health in Largo Caballero's government in November 1936. At a less dramatic level, women on the Republican side took up work in factories and transport in unprecedented numbers, often directly replacing their husbands or brothers or fathers who had been called up to fight.

Of course, there were also common experiences across the two zones. Everywhere women suffered from violence, bereavement and hardship. Moreover, the exigencies of war itself created new roles for women, just as they had done in the Great War of 1914-18.

Women took on the horrific duties of nursing seriously injured and dying soldiers on both sides, often in field hospitals that were themselves in danger of bombardment. The major Nationalist relief organisation, Social Aid, was largely the creation of a woman, Mercedes Sanz Bachiller, and mobilised thousands of women who distributed food and organised orphanages, canteens and other welfare services. Social Aid lorries with bread supplies followed conquering Nationalist armies into what had been Republican strongholds. Women joined other voluntaryrelief agencies too.

There was even a major female political figure in the Nationalist camp, Pilar Primo de Rivera, sister of José Antonio, the founder of the Falange, and herself the founder of its women's section before the war. She was thrown into a particularly important role firstly by the fact that José Antonio was in prison in Republican Alicante when the war began, and then by his execution, which occurred in November 1936 although it was not publicly confirmed until much later. In her brother's absence, then death, then elevation to the status of revered martyr of the Nationalist cause, Pilar became a national figure, leading the women's section which, like the Falange itself, swelled into a mass organisation in the summer of 1936. When Franco unified all political groups in Nationalist Spain in April 1937, it became the official women's section of the emerging regime.

On the other side, the image of female emancipation projected by the Republic was itself somewhat misleading. Women soldiers made excellent propaganda in the earlyweeks of the war, as young women rushed to defend Madrid and Barcelona against the military rising. But as early as September 1936, Largo Caballero's government decreed the withdrawal of women from the front, amid controversy about their role there. As irregular militias were replaced by the new Mixed Brigades of the reorganised Republican army, so the irregular presence of women at the front ended. It had been a feature of the urgency of the crisis rather than of any widespread view that soldiering was a proper activity for women.

Similarly, the extraordinary Dolores Ibárruri, member of the Central Committee of the PCE, galvanised the Anti-Fascist Women's Organisation, but insisted that its role was at the home front, not the battle front. Moreover, everything had to be subordinated to the war effort. She had little sympathy with the conviction of the Anarchist association Free Women, that their campaign for women's equality could continue even during the war.

Nonetheless, the difference between the two warring sides as far as gender roles were concerned was profound. Pilar Primo de Rivera became a major public figure in Nationalist Spain, but she used that position to insist that women's overwhelming mission in life was motherhood and the domestic sphere. Women were men's nurturers and helpers, not their competitors or work colleagues. The gender ideology of Franco's Spain was an extreme version of separate spheres, in which women were legally and culturally subordinate to men.

Men were warriors, leaders, workers and providers. Women were destined to bear children and look after the family. During the war, they were expected to dress soberly (and certainly not in trousers), to wear little or no make-up, and to avoid public entertainment like the theatre or cinema.

Divorce, introduced by the Second Republic, was abolished by the Nationalists. The Labour Charter enacted by the Franco regime in March 1938, and modelled on Mussolini's legislation of the same name, promised to 'liberate' married women from paid work. As early as September 1936, educational legislation ended the 'immoral' practice of co-education, and established separate syllabuses as well as separate schools for boys and girls. The emancipatory reforms of the Second Republic were swept away.

By contrast, the Republic at war, in all its various strands - revolutionary, democratic, Communist - continued to represent equal rights for women and men. Federica Montseny and Dolores Ibárruri held positions of political power that were inconceivable in Franco's Spain. The wartime autonomous Catalan government legalised abortion. Young women could wear unisex overalls or culottes, and did so because they were practical for the new tasks they were undertaking. In gender as well as in other aspects of political ideology, it was evident that the two warring sides represented, and if victorious would construct, quite different societies.

Terror

On both sides, the Spanish Civil War was peculiarly destructive. About half a million people died, out of a population of 24 million. Whole towns and villages were virtually obliterated, like Brunete, west of Madrid, and Belchite, in Saragossa. Families were also destroyed, both by death and by political divisions that sometimes pitted brother against brother, and father against son. The economy, too, was devastated.

Distinctions between life at the front and life behind the lines were often blurred. Nowhere was safe. Both in large cities like Madrid and Barcelona, and small country towns like Guernica and Durángo, Nationalist planes brought death and desolation in a way that foreshadowed the much larger-scale bombings of the Second World War. It is not surprising that when Pablo Picasso was asked to paint a picture for the Second Republic's stand at the International Exhibition in Paris in the summer of 1937, he chose to portray the human tragedy of Guernica, destroyed in April 1937 by the Condor Legion, rather than military confrontation in battle.

Guernica depicted the shattered lives and bodies of women, children, men at work and animals. This was the new reality of war. Civilians were also strafed from the air as they tried to move to safety. It was as dangerous to flee east from Malaga in February 1937 or west from Vizcaya in June, as it was to be a conscript at the front.

Most bombardment of civilians was done by the Nationalists, though the Republicans bombed cities held by their enemies, including Granada. The Nationalists also shelled and strafed civilians, as they took Republican territory and people fled rather than face retribution. But there was terror on both sides, especially in the early stages of the war, when there was no settled authority and very little restraint. Marxist and Anarchist revolutionaries seized the opportunity to rid the world of priests and the social elites, just as ruthlessly as Falangists, Carlists and army generals purged it of intellectuals, Republican politicians and town councillors, and trade union officials.

To be caught in the wrong place behind the lines in the summer of 1936 was a death warrant without appeal. Violence was widespread, ideologically driven and vicious. Extremists on left and right believed that the world could be reshaped by terror. The poet and playwright Federico Garcia Lorca was arrested by the Falange on 16 August 1936 in his home city of Granada. He was executed on the morning of 18 August. Garcia Lorca was 38 years old, an outstanding talent even in the glittering array of Spanish experimental writers of the 1920s and 1930s.

He was not interested in partisan politics. But his homosexuality and his plays, with their critique of the stifling effects of Catholic, bourgeois conventions, attracted the hatred of the new masters of Granada. His fame proved no protection.

Similarly, many died at Republican hands for what they symbolised rather than for any political actions. In the orgy of anti-clerical violence in the summer of 1936, the thousands of victims included young novices who had not even begun a religious ministry, and individuals like Father José Gafo, a courageous, lifelong campaigner for social justice. They were killed just because of their identification with the Catholic Church. Neither youth nor commitment to social reform saved them.

As the war progressed and governmental authority was asserted in both parts of Spain, uncontrolled actions by zealots became less frequent. Random arrests, and the dreaded paseos and sacas, in which prisoners were driven to a cemetery, or the verge of a country road, or a quiet spot outside a town, and shot, became less frequent. But the generals who had espoused violence in the first place when rising against the Republic showed few qualms in continuing to exercise it behind the lines as well as at the front. As the Nationalists occupied - or in their vocabulary, liberated - village after village, town after town, they brought with them bread and reprisals, even if the latter increasingly had a veneer of legality as peremptory military tribunals took over from sheer massacre.

On the Republican side, the popular tribunals that were established in September 1936 were an improvement on the frenzied vengeance of the summer, but they were a long way from representing the rule of law. And even in the last stages of the war, moments of military and political crisis provoked vengeance killings, such as that of Bishop Polanco early in 1939, during the rout of Republican forces in Catalonia.

Republicans increasingly feared hidden enemies. The Spanish Civil War created the term 'fifth column', or at least gave it popular currency, when General Mola famously looked forward - in vain - to taking Madrid early in the war with four columns approaching it from outside while a fifth sprang up within. But a fifth column certainly developed in Madrid, which had to wait until March 1939 before it could declare itself, but which in the meantime engaged in clandestine activities of liaison and sabotage.

Undeclared Francoists existed everywhere on Republican territory, as they were bound to do, including at the front. It was in the nature of this war to trap large numbers of people on the 'wrong' side, in circumstances where they had little choice but to hide their opinions and participate in the war effort of their political enemies. From government and the top of the military command downwards, fear of disloyalty was pervasive.

Rumours of deliberate sabotage greeted every major Republican defeat. Soviet advisers and Spanish Communist leaders were extremely sceptical about the reliability of Prime Minister Largo Caballero's Under-Secretary for War, General Asensio, and insisted on his removal from office after the fall of Malaga. He was later arrested on suspicion of treason after the fall of Gijón. He was a dramatic example of a widespread phenomenon. This was a war within one society, not between two different countries.

Who was to say what identity a man or woman held in their heart? The enemy was not just on the other side. The enemy could be anywhere.

In Republican Spain, however, the enemy within did not have to be a 'fascist'. He or she might be a genuine supporter of the Republic, but out of step with the dominant interpretation of what the Republic should be like. From October 1936, when the Soviet Union came to the aid of the Republic, the influence of the Spanish Communist party, and more particularly of Stalin, the Comintern and the Soviet Union, grew ever stronger. Without Soviet supplies, the Republic could not have withstood the armies of Nationalist Spain, backed up by the Nazis and Fascists.

Communist exasperation with Largo Caballero was a major reason for his downfall as Prime Minister in May 1937, although many non-Communists also wanted him out of office. Similarly, Communist support for Juan Negrín, and his closeness, most of the time, to Soviet priorities in Spain, were essential factors sustaining his premiership from May 1937 until the last days of the war. Those priorities were straightforward. It was the policy of the Soviet Union, the PCE, a large section of the Socialist party and what remained of the left-Republicans to concentrate on the war effort, and to persuade the western democracies that this was a confrontation between a democratic regime and international fascism. Winning the war and drawing Britain and France into an alliance against Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy were the dual, and closely interrelated, aims. There was no room in this agenda for the social revolution that Anarchists, the small anti-Stalinist Communist movement (the POUM) and left-Socialists launched in the early days and weeks of the war. George Orwell was exhilarated by his experience of revolutionary Barcelona in 1936, where a new, classless society seemed to be being created. Of course, conservatives, propertyowners and Catholics feared the revolution.

But so too did Communists and many others on the left who were aghast at what seemed to them irresponsible forgetfulness of the main priority, which was fighting fascism. Communist political commissars, secret police and political prisons set about imposing that priority in ways that earned the Communist movement the hatred and distrust of their rivals. The torture and killing of the POUM leader Andreu Nin while imprisoned by the Communists was a particularly vicious, but not unrepresentative instance of the political purge undertaken behind the Republican lines.

Long after the armed confrontation between the revolutionaries and their opponents in May 1937 in Barcelona, which the former lost, and the subsequent removal from government of Anarchist ministers, Communists continued to harry and repress those who did not accept PCE priorities and discipline. The Anarchist trade union organisation the CNT, which had been so dominant in Catalonia and Aragón in the first weeks of the war, was a much reduced and disaffected force in its later stages, as could be seen in the collapse of the Aragón front after the Ebro campaign, and the inability to defend Barcelona as the Nationalists approached. Ideological conflict weakened the Republic at war, and brought danger and death far behind the Republican lines.[1]

Franco's Volksgemeinschaft[2]

Aquí la flama de l'esperit és un record vague, una història perduda

(Here the spark of human spirit is a dim memory, a lost history)

(Agustí Bartra, Tercera elegia)

In this place nothing belongs to you (Warder, Les Corts Prison, Barcelona, 1942)The space of the camp and of 'war without limit' also existed inside Spain. Francisco Boix's own father died in political incarceration there in 1942. Like the Nazi new order of which it aspired to be a part, Francoist Spain too was to be constructed as a monolithic community by means of the brutal exclusion of specific categories of people.

Those excluded, broadly speaking, were defeated Republican constituencies who could not leave Spain: urban workers, the rural landless, regional nationalists, liberal professionals, and 'new' women - groups that had challenged the established order culturally, politically, or economically. For the Franco regime they were all 'reds' and, once placed beyond the nation, they were deemed to be without rights.

Tens of thousands were executed - judicially murdered after summary military trials. Hundreds of thousands more men, women, and children spent time in what historians now term 'the penal universe' of Francoism: reformatories and prisons, concentration camps and forced labour battalions, where the military forces detached to organize these referred to themselves as 'the army of occupation'. Those confined were subject to a sustained and brutal attempt to reconfigure their consciousness and values.

To this end, tens of thousands found themselves coerced, maltreated, and humiliated on a daily basis. Sometimes, however, the pressure applied was even greater. Matilde Landa, a leading political activist whose death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in 1939, used her experience of the law to establish one of the first legal aid services for her fellow prisoners. Partly because she was famous and partly because she was an educated woman of 'good' birth, and thus deemed 'recuperable' according to regime tenets, huge efforts were exerted to make her repudiate her political views and to accept baptism and confession. She was even promised her freedom in return for a public 'recantation'. When this failed, Landa was repeatedly held in solitary confinement for longer and longer periods of time. Transferred from Madrid to the women's gaol in Palma de Mallorca, where the coercion continued, Matilde Landa fell to her death from an internal prison window on 26 September 1942 in what may have been suicide.

Among the other victims of the Francoist worldview were the 'lost children'. These were the babies and young children who, after being removed from their imprisoned mothers, had their names changed so they could be adopted by regime families. Many thousands of working-class children were also sent to state institutions because the authorities considered their own Republican families 'unfit' to raise them. The Franco regime spoke of the 'protection of minors'. But this idea of protection was integrally linked to regime discourses of punishment and purification. In theory, the punishment was of the parents, the 'redemption', or 'rehabilitation', of the children. But the reality, as experienced by Republican children, was of an ingrained belief in state personnel (religious in particular, but others too) that the children had actively to expiate the 'sins of the fathers'. Yet, at the same time, the children were repeatedly told that they too were irrecuperable. As such, they were frequently segregated from other classes of inmate in state institutions and mistreated both physically and mentally in other ways.

One child who endured both a Nazi concentration camp and a Francoist reformatory in 1940s Barcelona has written of their fundamental institutional similarities as factories of dehumanization, while another 'lost child' of the Francoist institutions, interviewed in his 70s for a television documentary, spoke of the 'real him' as having died during his incarceration in the 1940s. His comment eerily evokes the idea of the concentration camp revenant. As Jorge Semprún remarked, one did not 'return' from the camps, except as a ghost.