PTO - Pacific Theater of Operations P-38 Lightning slideshow

Pacific Theater of Operations PTO P-38 Lightning photo's gallery

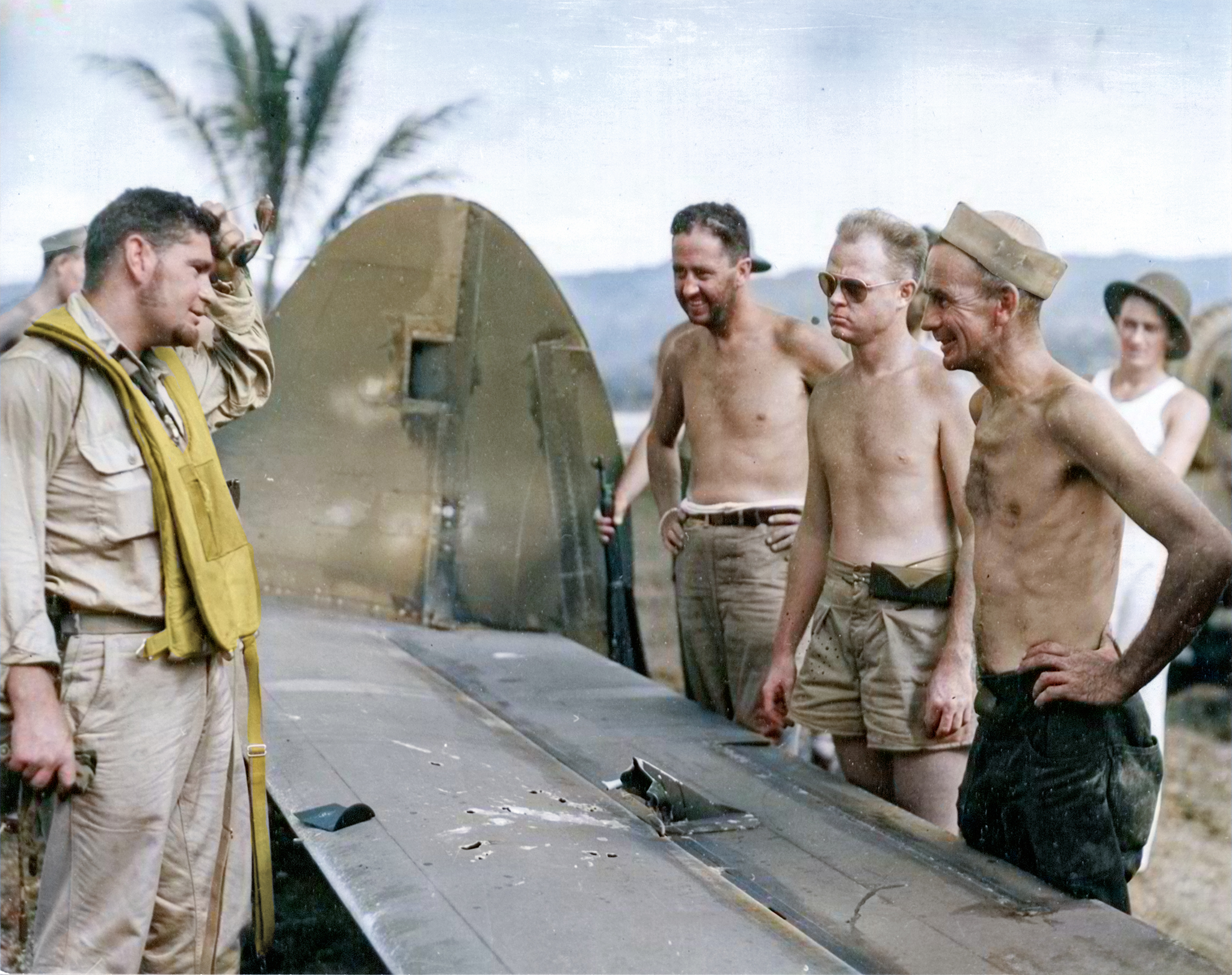

American 13AF 347FG339FS P-38 ace Lt Murray J Shubin who shot down five Jap Zeros over Guadalcanal 1942 NA300

Photo description: 339th Fighter Squadron, 347th Fighter Group, Thirteenth Air Force. P-38 Pilot gets 5 Zeros in 45 Minutes. Lt. Murray J. Shubin of the 14th Army Air Forces in the South West Pacific became an ace in the record time of 45 minutes recently. He shot down five Jap Zeros over Guadalcanal with one more "probable11. his P-38 Lightning is named "Oriole11 after the Australian girl who is his fiancee. Lt. Shubin's home is in Pittsburgh, Pa. (U.S. Air Force Number 24514AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204985640 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43614-24514AC

World War II

Several months after being commissioned to second lieutenant, Shubin deployed to Guadalcanal, flying P-38 Lightnings with the 339th Fighter Squadron, 347th Fighter Group, Thirteenth Air Force.[1] At Guadalcanal, Shubin took part in bombing and strafing missions, along with B-17 escort missions targeting Japanese ships at Bougainville.[2] On February 2, 1943, Shubin shot down his first Japanese plane. His next victory would not come until June 7.

Ace in a day

On June 16, 1943, Shubin's fighter group intercepted a large force of Japanese aircraft flying towards the Russell Islands. He was leading three other P-38s at 27,000 feet when he spotted 50 enemy planes 4,000 feet below them off Guadalcanal. Diving on a group of approximately 15 A6M Zeros at the rear of the formation, he and two other pilots all quickly shot one down. One Zero then pulled up in a climb directly in front of Shubin, and he destroyed it as well.

One of the other P-38s was damaged and returned to the airfield. A second P-38 pilot shot down two more Zeros before his guns jammed. He returned home as well, with the third P-38 escorting him, leaving Shubin in the fight by himself with five remaining enemy planes.

Shubin struck the first plane in the cockpit, causing it to fall from the sky. He then managed to fire a well-placed deflection shot on the second Zero, hitting it in the engine and causing it to dive as well. After several diving attempts on the last three Zeros, Shubin riddled the third plane along the entire length of the fuselage, causing it to crash.

The two final Zeros were circling above Savo Island and Shubin attacked them from the rear. He missed the fourth Zero and it was able to fly away. The fifth Zero attacked Shubin head-on and they both missed each other. He managed to turn around and hit the fifth plane, causing it to crash.

Shubin only listed two confirmed kills for himself that day with the other four he shot down listed as probables as he was unable to observe whether any of them actually crashed. However, an officer with the 35th Infantry Regiment had watched the dogfight through his binoculars at Guadalcanal, and confirmed three of the Zeros originally listed as probables. Additionally, his sixth probably may have been confirmed by ground troops as well. These confirmations meant Shubin had shot down five or six enemy planes in a period of 45 minutes, making him an ace in a day.[6] For his actions that day, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Web Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murray_J._Shubin

42-67795 P-38J Lightning 18FG44FS on Guadalcanal Solomon Islands in early 1944 NA815

42-67795 P-38J Lightning 18FG44FS on Guadalcanal Solomon Islands in early 1944 NA817

Photo description: P-38J 42-67795 was assigned to the 44th Ftr Sq on Guadalcanal in early 1944. It was eventually written off in a crash on 13 February 1945 near Lae, New Guinea. (U.S. Air Force Number 67803AC); A fighter pilot of the 13th Air Force takes time out from the exigencies of war to do his laundry. Sometimes the facilities aren't available to do a real job so the men use anything available to do their washing. In this case the wing of a Lockheed P-38 is used in lieu of a clothes line. Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. (U.S. Air Force Number A67803AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204986486 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43935-67803AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204986489 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43936-A67803ACAmerican 13AF 44FS P-38 ace Maj Robert B Westbrook CO was the leading ace 1944 NA322

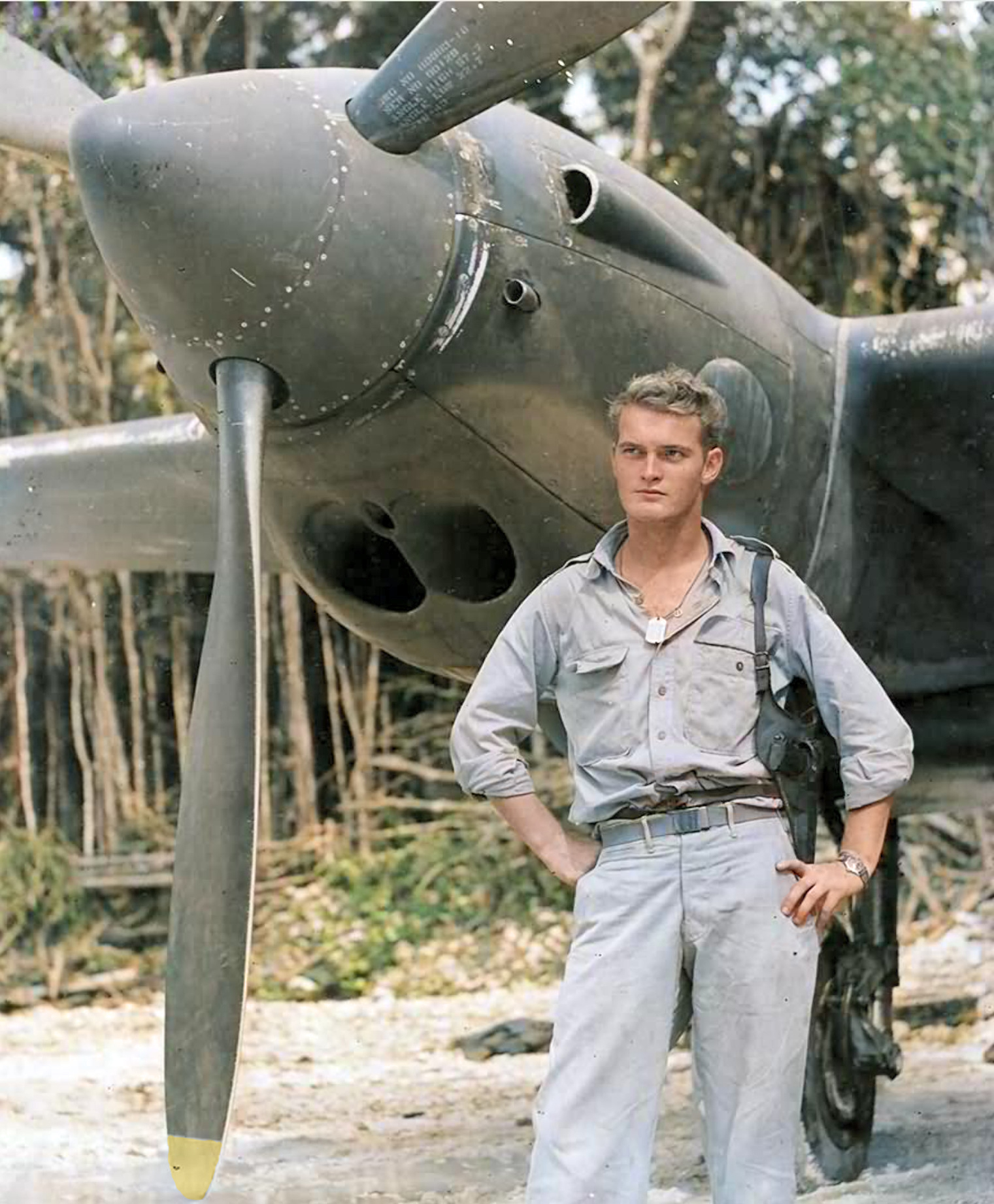

Photo description: MAJ Robert B. Westbrook, Jr, 44th Ftr Sq "Vampires," was the leading ace in 13th Air Force when this photo was taken, officially credited with fifteen confirmed aerial victories. Rising to the ranl of Lieutenant Colonel, he took command of the 347th FG and added another five 'kills' to his tally before he was KIA. (U.S. Air Force Number 93221AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204995378 Local ID: 342-FH-3A47180-93221AC

Westbrook applied for United States Army Air Corps flight training later that year and was accepted. He was awarded his wings with Class 42-G at Luke Field, Arizona, on July 26, 1942, and then ordered to Hawaii. On August 15, he joined the 44th Fighter Squadron of the 18th Fighter Group. which was equipped with the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, at Bellows Field on Oahu.

World War II

Westbrook was promoted to first lieutenant in October, and on October 20, the 44th FS pilots and ground crews were transported to New Caledonia. Shortly thereafter, the squadron's P-40s arrived at the port of Espiritu Santo. When the planes were operational, the pilots flew them from Espiritu to their new base on the nearby island of Efate.

The 44th FS became part of the 13th Air Force when it was activated on January 13, 1943. A week later, its pilots flew their planes to Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, from which they began flying combat missions. Westbrook scored his first kill on January 13, 1943, when he shot down an A6M Zero, during an intercept of an Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service raid on Guadalcanal consisting of nine Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bombers escorted by 30 A6M Zeros. On February 14, while flying a bomber escort of B-24 Liberators, Westbrook shot down one enemy fighter, while other P-40 pilots shot down four and probably destroyed two others. Westbrook received his first Silver Star for this mission. On April 14, the 44th FS was assigned at Guadalcanal with the 18th Fighter Group. Westbrook was promoted to captain in early May. On June 7, during an interception of more than 40 A6M Zeroes over Guadalcanal, he shot down two Zeroes, bringing his total to four aerial victories.

P-38 Lightning

On June 12, Westbrook shot down a Zero near the Russell Islands, northwest of Guadalcanal. This was his fifth aerial victory and this made him the first flying ace of the 44th FS. He scored his final aerial victories in the P-40, when he shot down a Nakajima A6M2-N "Hap" and a Zero, while protecting Allied ships that were supporting the landings on New Georgia and Rendova Islands. On September 25, 1943, Westbrook was promoted to major and became commander of the 44th Fighter Squadron. The 44th FS transitioned from the P-40 to Lockheed P-38 Lightning. Westbrook flew his first combat mission in the P-38 on October 10 and on the same day, while flying a bomber escort with the 339th Fighter Squadron, he shot down one enemy airplane and shared destruction of another, crediting him with 44th FS' first aerial victories while flying the P-38. On September 1943, Westbrook was promoted to major and became commander of the 44th Fighter Squadron.

During December 1943, he shot down six Japanese planes in a three-day span over Rabaul, for which he received the Distinguished Service Cross. On January 6, 1944, during a fighter sweep over Rabaul, Westbrook was credited with the confirmed destruction of one enemy aircraft, which was his fifteenth aerial victory, and another probable enemy aircraft destroyed. It was his last mission with the 44th FS, before he was sent back to the United States for shore leave.

Westbrook returned to Guadalcanal and in May 1944, he was appointed deputy commanding officer of the 347th Fighter Group and was promoted to lieutenant colonel. The 347th FG was then based on Stirling Island and on September 25, Westbrook shot down a Nakajima Ki-43 "Oscar" over Kendari. Five days later, he shot down another Ki-43 near an aerodrome in Boroboro, Southeast Sulawesi. On August, the 347th moved to Sansapor in Western Papua and then to nearby Middleburg Island in September. He was appointed as aide to the commander of the Thirteenth Air Force.[5] On October 23, Westbrook shot down three Ki-43s over Boeloedowang Aerodrome near Makassar, his last aerial victories of the war. The 347th FG was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation for three missions in November.

During World War II, Westbrook flew a total of 367 combat missions. He was credited with the destruction of 20 enemy aircraft in aerial combat, which includes 13 in P-38 Lightning and 7 in P-40 Warhawk. With 20 victories, Westbrook became the Thirteenth Air Force's highest scoring ace.

Death

On November 22, 1944, Westbrook was leading the flight to destroy the Japanese naval convoys in Makassar bay is a strait between the islands of Borneo and Sulawesi in Indonesia. The flight proceeded to destroy or heavily damage 13 vessels by strafing. While strafing a Japanese gunboat, Westbrook's P-38 was hit by anti-aircraft fire from the convoy. He leveled his P-38 in an attempt to make a water landing, but the P-38 turned its nose down and slammed into the water, killing him instantly. His wingman was also shot down in the same mission, but was rescued by an U.S. Navy PBY Catalina. Westbrook's remains were never recovered.

43-2264 P-38G Lightning 347FG339FS Miss Virginia on Guadalcanal Solomon Islands 18th April 1943 NA1177

Photo description: P-38G 43-2264 would be the "Lightning" assigned to CAPT Robert L. Petit of the 339th Ftr Sq, 347th FG on Guadalcanal, nicknamed "Miss Virginia." Rex Barber borrowed this ship for the 18 April 1943 mission to intercept Yamamoto. In the process of shooting down the Japanese 'Betty' bomber on which the Admiral was riding, Barber made it home to count over 100 holes from enemy fire in Petit's ship. Following repairs, the bird returned to service for a month or so before this forced landing and subsequent salvage. The plane that shot down Yamamoto - Rex T. Barber borrowed Robert L. Petit's P-38 Lightning, nicknamed "Miss Virginia," for Operation Vengeance and returned it with over 100 bullet holes (U.S. Air Force Number 66919AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204987073 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44126-66919AC

South West Pacific Area Theater of Operations SWPA P-38 Lightning photo's gallery

American 13AF 347FG339FS P-38 ace Lt Murray J Shubin who shot down five Jap Zeros over Guadalcanal 1942 NA300

Photo description: 339th Fighter Squadron, 347th Fighter Group, Thirteenth Air Force. P-38 Pilot gets 5 Zeros in 45 Minutes. Lt. Murray J. Shubin of the 14th Army Air Forces in the South West Pacific became an ace in the record time of 45 minutes recently. He shot down five Jap Zeros over Guadalcanal with one more "probable11. his P-38 Lightning is named "Oriole11 after the Australian girl who is his fiancee. Lt. Shubin's home is in Pittsburgh, Pa. (U.S. Air Force Number 24514AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204985640 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43614-24514AC

World War II

Several months after being commissioned to second lieutenant, Shubin deployed to Guadalcanal, flying P-38 Lightnings with the 339th Fighter Squadron, 347th Fighter Group, Thirteenth Air Force.[1] At Guadalcanal, Shubin took part in bombing and strafing missions, along with B-17 escort missions targeting Japanese ships at Bougainville.[2] On February 2, 1943, Shubin shot down his first Japanese plane. His next victory would not come until June 7.

Ace in a day

On June 16, 1943, Shubin's fighter group intercepted a large force of Japanese aircraft flying towards the Russell Islands. He was leading three other P-38s at 27,000 feet when he spotted 50 enemy planes 4,000 feet below them off Guadalcanal. Diving on a group of approximately 15 A6M Zeros at the rear of the formation, he and two other pilots all quickly shot one down. One Zero then pulled up in a climb directly in front of Shubin, and he destroyed it as well.

One of the other P-38s was damaged and returned to the airfield. A second P-38 pilot shot down two more Zeros before his guns jammed. He returned home as well, with the third P-38 escorting him, leaving Shubin in the fight by himself with five remaining enemy planes.

Shubin struck the first plane in the cockpit, causing it to fall from the sky. He then managed to fire a well-placed deflection shot on the second Zero, hitting it in the engine and causing it to dive as well. After several diving attempts on the last three Zeros, Shubin riddled the third plane along the entire length of the fuselage, causing it to crash.

The two final Zeros were circling above Savo Island and Shubin attacked them from the rear. He missed the fourth Zero and it was able to fly away. The fifth Zero attacked Shubin head-on and they both missed each other. He managed to turn around and hit the fifth plane, causing it to crash.

Shubin only listed two confirmed kills for himself that day with the other four he shot down listed as probables as he was unable to observe whether any of them actually crashed. However, an officer with the 35th Infantry Regiment had watched the dogfight through his binoculars at Guadalcanal, and confirmed three of the Zeros originally listed as probables. Additionally, his sixth probably may have been confirmed by ground troops as well. These confirmations meant Shubin had shot down five or six enemy planes in a period of 45 minutes, making him an ace in a day.[6] For his actions that day, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Web Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murray_J._Shubin

42-67795 P-38J Lightning 18FG44FS on Guadalcanal Solomon Islands in early 1944 NA815

42-67795 P-38J Lightning 18FG44FS on Guadalcanal Solomon Islands in early 1944 NA817

Photo description: P-38J 42-67795 was assigned to the 44th Ftr Sq on Guadalcanal in early 1944. It was eventually written off in a crash on 13 February 1945 near Lae, New Guinea. (U.S. Air Force Number 67803AC); A fighter pilot of the 13th Air Force takes time out from the exigencies of war to do his laundry. Sometimes the facilities aren't available to do a real job so the men use anything available to do their washing. In this case the wing of a Lockheed P-38 is used in lieu of a clothes line. Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. (U.S. Air Force Number A67803AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204986486 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43935-67803AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204986489 Local ID: 342-FH-3A43936-A67803ACAmerican 347FG P-38 ace Maj Robert B Westbrook CO after his 17th victory 30th Sep 1944 NA1170

American 13AF 44FS P-38 ace Maj Robert B Westbrook CO was the leading ace 1944 NA322

Photo description: MAJ Robert B. Westbrook, Jr, 44th Ftr Sq "Vampires," was the leading ace in 13th Air Force when this photo was taken, officially credited with fifteen confirmed aerial victories. Rising to the ranl of Lieutenant Colonel, he took command of the 347th FG and added another five 'kills' to his tally before he was KIA. (U.S. Air Force Number 93221AC); Lt. Col. Robert E, Westbrook, Hollywood, Calif., leading ace of the 13th AAF, shot down his 17th Jap plane on 30 Sep 1944 over Jap-held Kendari field in the Southern Celebes. Flying a long range Lockheed P-38 Lightning, Col, Westbrook led seven fighters of the 13th AAF's Fighting Cocks Unit on the long, 1500 mile bomber escort mission.(U.S. Air Force Number 54994AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NA322 NAID: 204995378 Local ID: 342-FH-3A47180-93221AC

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NA1170 NAID: 204989122 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44866-54994AC

Westbrook applied for United States Army Air Corps flight training later that year and was accepted. He was awarded his wings with Class 42-G at Luke Field, Arizona, on July 26, 1942, and then ordered to Hawaii. On August 15, he joined the 44th Fighter Squadron of the 18th Fighter Group. which was equipped with the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, at Bellows Field on Oahu.

World War II

Westbrook was promoted to first lieutenant in October, and on October 20, the 44th FS pilots and ground crews were transported to New Caledonia. Shortly thereafter, the squadron's P-40s arrived at the port of Espiritu Santo. When the planes were operational, the pilots flew them from Espiritu to their new base on the nearby island of Efate.

The 44th FS became part of the 13th Air Force when it was activated on January 13, 1943. A week later, its pilots flew their planes to Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, from which they began flying combat missions. Westbrook scored his first kill on January 13, 1943, when he shot down an A6M Zero, during an intercept of an Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service raid on Guadalcanal consisting of nine Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bombers escorted by 30 A6M Zeros. On February 14, while flying a bomber escort of B-24 Liberators, Westbrook shot down one enemy fighter, while other P-40 pilots shot down four and probably destroyed two others. Westbrook received his first Silver Star for this mission. On April 14, the 44th FS was assigned at Guadalcanal with the 18th Fighter Group. Westbrook was promoted to captain in early May. On June 7, during an interception of more than 40 A6M Zeroes over Guadalcanal, he shot down two Zeroes, bringing his total to four aerial victories.

P-38 Lightning

On June 12, Westbrook shot down a Zero near the Russell Islands, northwest of Guadalcanal. This was his fifth aerial victory and this made him the first flying ace of the 44th FS. He scored his final aerial victories in the P-40, when he shot down a Nakajima A6M2-N "Hap" and a Zero, while protecting Allied ships that were supporting the landings on New Georgia and Rendova Islands. On September 25, 1943, Westbrook was promoted to major and became commander of the 44th Fighter Squadron. The 44th FS transitioned from the P-40 to Lockheed P-38 Lightning. Westbrook flew his first combat mission in the P-38 on October 10 and on the same day, while flying a bomber escort with the 339th Fighter Squadron, he shot down one enemy airplane and shared destruction of another, crediting him with 44th FS' first aerial victories while flying the P-38. On September 1943, Westbrook was promoted to major and became commander of the 44th Fighter Squadron.

During December 1943, he shot down six Japanese planes in a three-day span over Rabaul, for which he received the Distinguished Service Cross. On January 6, 1944, during a fighter sweep over Rabaul, Westbrook was credited with the confirmed destruction of one enemy aircraft, which was his fifteenth aerial victory, and another probable enemy aircraft destroyed. It was his last mission with the 44th FS, before he was sent back to the United States for shore leave.

Westbrook returned to Guadalcanal and in May 1944, he was appointed deputy commanding officer of the 347th Fighter Group and was promoted to lieutenant colonel. The 347th FG was then based on Stirling Island and on September 25, Westbrook shot down a Nakajima Ki-43 "Oscar" over Kendari. Five days later, he shot down another Ki-43 near an aerodrome in Boroboro, Southeast Sulawesi. On August, the 347th moved to Sansapor in Western Papua and then to nearby Middleburg Island in September. He was appointed as aide to the commander of the Thirteenth Air Force.[5] On October 23, Westbrook shot down three Ki-43s over Boeloedowang Aerodrome near Makassar, his last aerial victories of the war. The 347th FG was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation for three missions in November.

During World War II, Westbrook flew a total of 367 combat missions. He was credited with the destruction of 20 enemy aircraft in aerial combat, which includes 13 in P-38 Lightning and 7 in P-40 Warhawk. With 20 victories, Westbrook became the Thirteenth Air Force's highest scoring ace.

Death

On November 22, 1944, Westbrook was leading the flight to destroy the Japanese naval convoys in Makassar bay is a strait between the islands of Borneo and Sulawesi in Indonesia. The flight proceeded to destroy or heavily damage 13 vessels by strafing. While strafing a Japanese gunboat, Westbrook's P-38 was hit by anti-aircraft fire from the convoy. He leveled his P-38 in an attempt to make a water landing, but the P-38 turned its nose down and slammed into the water, killing him instantly. His wingman was also shot down in the same mission, but was rescued by an U.S. Navy PBY Catalina. Westbrook's remains were never recovered.

43-2264 P-38G Lightning 347FG339FS Miss Virginia on Guadalcanal Solomon Islands 18th April 1943 NA1177

Photo description: P-38G 43-2264 would be the "Lightning" assigned to CAPT Robert L. Petit of the 339th Ftr Sq, 347th FG on Guadalcanal, nicknamed "Miss Virginia." Rex Barber borrowed this ship for the 18 April 1943 mission to intercept Yamamoto. In the process of shooting down the Japanese 'Betty' bomber on which the Admiral was riding, Barber made it home to count over 100 holes from enemy fire in Petit's ship. Following repairs, the bird returned to service for a month or so before this forced landing and subsequent salvage. The plane that shot down Yamamoto - Rex T. Barber borrowed Robert L. Petit's P-38 Lightning, nicknamed "Miss Virginia," for Operation Vengeance and returned it with over 100 bullet holes (U.S. Air Force Number 66919AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204987073 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44126-66919AC

Lockheed P-38L Lightning 13AF 347FG339FS crashed on landing at Lingayen Airstrip Luzon Philippines Feb 1945 NA1145

Photo description: This Lockheed P-38 crashed on landing at Lingayen Airstrip, Luzon Island, Philippine Islands. Though the plan© was completely washed out, the pilot was uninjured. Mechanic standing in the cockpit is salvaging instruments and other undamaged accessory parts. February 1945. (U.S. Air Force Number 63889AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204951451 Local ID: 342-FH-3A31020-63889AC

American 5AF P-38 ace 1Lt John L Jones credited with Nine Japanese planes over Southwest Pacific 1943 NA1204

Photo description: First Lieut. John L. Jones (Rfd 1, Pines Road, Paterson, N.J.), Fifth Air Force Fighter Pilot, Now Officially Credited With Having Shot Down Nine Japanese Planes In Combat In The Southwest Pacific. (U.S. Air Force Number 66859AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204989175 Local ID: 342-FH-3A44883-66859AC

USAAF Lockheed F-5A Lightning 7AF taking off at Ewajalein Marshall Islands 5th July 1944 NA291

Photo description: Lockheed F-5A takin,- off from an airfield on Kwajalein, .Marshall islands, 4 July 1944. (U.S. Air Force Number 63788AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204979436 Local ID: 342-FH-3A41421-63788AC

USAAF Lockheed F-5A Lightning 7AF at Ewajalein Marshall Islands 5th July 1944 NA291

Photo description: Two Lockheed F-5A's, a North American B-25 Mitchell and a Consolidated B-24 "Liberator" at an airfield on Kwajalein, Marshall Islands July 1944 (U.S. Air Force Number 63786AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204979433 Local ID: 342-FH-3A41420-63786AC

44-23993 Lockheed P-38L Lightning factory fresh from USA at Hickam Field Oahu Hawaii NA

Photo description: (U.S. Air Force Number 63934AC)

Photo Source: National Archives Identifier NAID: 204977841 Local ID: 342-FH-3A40840-63934AC

3rd Air Commando Group

Constituted as 3rd Air Commando Group on 25 Apr 1944. Activated on 1 May 1944. Moved to the Philippines late in 1944. Assigned to Fifth AF for operations with P-51, C-47, and L-5 aircraft. Attacked Japanese airfields and installations in the Philippines, supported ground forces on Luzon, provided escort for missions to Formosa and the China coast, made raids on airfields and railways on Formosa, and furnished cover for convoys. Also transported personnel, dropped supplies to ground troops and guerrilla forces, evacuated casualties from front-line strips, adjusted artillery fire, and flew courier and mail routes. Moved to the Ryukyus in Aug 1945. Flew some patrols over Japan, made local liaison flights, and hauled cargo from the Philippines to Okinawa. Moved to Japan in Oct 1945. Inactivated on 25 Mar 1946. Disbanded on 8 Oct 1948.

Squadrons. 3rd Fighter: 1944-1946. 4th Fighter: 1944-1946. 157th Liaison: 1944-1946. 159th Liaison: 1944-1946. 160th Liaison: 1944-1946. 318th Troop Carrier: 1944-1946.

Stations. Drew Field, Fla, 1 May 1944; Lakeland AAFld, Fla, 5 May 1944; Alachua AAFld, Fla, 20 Aug 1944; Drew Field, Fla, 6-24 Oct 1944; Leyte, Dec 1944; Mangaldan, Luzon, c. 26 Jan 1945; Laoag, Luzon, Apr 1945; Ie Shima, Aug 1945; Chitose, Japan, c. 27 Oct 1945-25 Mar 1946.

Commanders. Maj Klem F Kalberer, May 1944; Col Arvid E Olson Jr, Jun 1944; Lt Col Walker M Mahurin, Sep 1945; Lt Col Charles H Terhune, 20 Oct 1945-unkn.

Campaigns. Air Offensive, Japan; China Defensive; Western Pacific; Leyte; Luzon; China Offensive.

Decorations. Philippine Presidential Unit Citation.

Insigne. None.

USAAF 18th Pursuit Group (Interceptor) - 18th Fighter Group18th Fighter Group

Organized as 18th Pursuit Group in Hawaii in Jan 1927. Redesignated 18th Pursuit Group (Interceptor) in 1939, and 18th Fighter Group in 1942. Before World War II the group engaged in routine flying and gunnery training and participated in joint Army-Navy maneuvers, using DH-4, PW-9, P-12, P-26, P-36, and other aircraft. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 Dec 1941, the group, which had recently converted to P-40's, sustained severe losses. The two planes that its pilots were able to get into the air during the attack were quickly shot down. The group, assigned to Seventh AF in Feb 1942, had to be re-equipped before it could resume training and begin patrol missions.

Moved to the South Pacific in Mar 1943. Assigned to Thirteenth AF. Began operations from Guadalcanal. Flew protective patrols over US bases in the Solomons; later, escorted bombers to the Bismarcks, supported ground forces on Bougainville, and attacked enemy airfields and installations in the northern Solomons and New Britain. Used P-38, P-39, P-61, and P-70 aircraft. Moved to New Guinea in Aug 1944. Equipped with P-38's. Escorted bombers to targets in the southern Philippines and Borneo, and attacked enemy airfields and installations in the Netherlands Indies. Received a DUC for actions at Ormoc Bay: on 10 Nov 1944 the group withstood intense flak and vigorous opposition from enemy interceptors to attack a Japanese convoy that was attempting to bring in additional troops for use against American forces that had landed on Leyte; on the following day a few of the group's planes returned to the same area, engaged a large force of enemy fighters, and destroyed a number of them. Moved to the Philippines in Jan 1945. Supported ground forces on Luzon and Borneo, attacked shipping in the central Philippines, covered landings on Palawan, attacked airfields and railways on Formosa, and escorted bombers to such widely-scattered targets as Borneo, French Indochina, and Formosa.

Remained in the Philippines as part of Far East Air Forces after the war. Flew patrols and trained with F-80's. Lost all personnel in Mar 1947 but was remanned in Sep 1947. Equipped first with F-47's, later with F-51's, and still later (1949) with F-80's. Redesignated 18th Fighter-Bomber Group in Jan 1950.

Moved to Korea in Jul 1950 and entered combat, using F-51's. Supported UN ground forces and attacked enemy installations and supply lines. Maj Louis Sebille was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his action on 5 Aug 1950: although his plane was badly damaged by flak while attacking a concentration of enemy trucks, Maj Sebille continued his strafing passes until he crashed into an armored vehicle. The group converted to F-86's early in 1953 and remained in Korea for some time after the war. Moved to Okinawa in Nov 1954.

6th FS - 12th FS - 19th FS - 19th FS - 44th FS - 55th FS - 67th FS - 68th FS - 70th FS - 73th FS - 74th FS - 74th FS - 78th FS - 333d FS - 333d FS - 419th FS

Squadrons. 6th: 1927-1943. 12th: 1943-. 19th: 1927-1943. 36th: 1931-1932. 44th: 1941-1942, 1943-. 55th: 1931. 67th: 1945-. 68th: 1945-. 70th: 1943-1945. 73d: 1929-1931, 1941-1942. 74th: 1929-1932. 78th: 1940-1943. 333d: 1942-1943. 419th: 1943-1944.

Stations. Wheeler Field, TH, Jan 1927; Espiritu Santo, 11 Mar 1943; Guadalcanal, 17 Apr 1943; Sansapor, New Guinea, 23 Aug 1944; Lingayen, Luzon, c. 13 Jan 1945; San Jose, Mindoro, c. 1 Mar 1945; Zamboanga, Mindanao, 4 May 1945; Palawan, 10 Nov 1945; Floridablanca, Luzon, Mar 1946; Clark Field, Luzon, 16 Sep 1947; Taegu, Korea, 28 Jul 1950; Ashiya, Japan, 8 Aug 1950; Tongnae, Korea, 8 Sep 1950; Pyongyang, Korea, c. 21 Nov 1950; Suwon, Korea, 1 Dec 1950; Chinhae, Korea, 9 Dec 1950; Hoengsong, Korea, 26 Dec 1952; Osan-Ni, Korea, 11 Jan 1953; Kadena AB, Okinawa, 1 Nov 1954-.

Commanders. Unkn, 1927-1940; Maj Kenneth M Walker, 22 Mar 1940; Maj William R Morgan, 1941; Lt Col Aaron W Tyer, Dec 1941; Lt Col W H Councill, 10 Dec 1943; Col Milton B Adams, 8 Jul 1944; Col Harry L Donicht, 24 May 1945; Lt Col Bill Harris, 1 Aug 1945; Lt Col Wilbur Grumbles, 18 Oct 1945-unkn; Col Victor R Haugen, 1946; Col Homer A Boushey, 7 Aug 1946-Mar 1947; Maj Kenneth M Taylor, 16 Sep 1947; Lt Col Joseph Kruzel, 1 Oct 1947; Col Marion Malcolm, 3 Sep Lt Col Henry H Norman Jr, 24 Jul 1949; Col Ira L Wintermute, 16 Jun 1950; Lt Col Homer M Cox, 20 Feb 1951; Col William P McBride, May 1951; Col Ralph H Saltsman Jr, 5 Jun 1951; Col Seymour M Levenson, 30 Nov 1951; Col Sheldon S Brinson, 17 May 1952; Lt Col Albert Freund Jr, 25 Nov 1952; Col Maurice L Martin, 24 Jan 1953; Lt Col Edward L Rathbun, 17 Dec 1953; Col John H Buckner, 1 Feb 1954; Lt Col Edward L Rathbun, 24 May 1954; Lt Col Clifford P Patton, 17 Aug 1954; Col Nathan Adams, 7 Sep 1954; Col John B Murphy, 1 Nov 1954; Lt Col Clifford P Patton, 10 Nov 1954; Col Paul E Hoeper, 1 Jan 1955; Lt Col Joseph E Andres, 22 Jul 1955; Col Leo C Moon, 21 Nov 1955-.

Campaigns. World War II: Central Pacific; China Defensive; New Guinea; Northern Solomons; Bismarck Archipelago; Western Pacific; Leyte; Luzon; Southern Philippines. Korean War: UN Defensive; UN Offensive; CCF Intervention; 1st UN Counteroffensive; CCF Spring Offensive; UN Summer-Fall Offensive; Second Korean Winter; Korea Summer-Fall, 1952; Third Korean Winter; Korea Summer-Fall, 1953.

Decorations. Distinguished Unit Citations: Philippine Islands, 1-11 Nov 1944; Korea, 3 Nov 1950-24 Jan 1951; Korea, 22 Apr-8 Jul 1951. Philippine Presidential Unit Citation. Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citations: 24 Jul 1950-31 Jan 1951; 1 Feb 1951-31 Mar 1953.

Insigne Shield: Or, a fighting cock with wings displayed sable wattled and combed gules. Crest: On a wreath or and sable two wings conjoined and displayed tenne (orange). Motto: Unguibus Et Rostro - With Talons and Beak. (Approved 21 Feb 1931.)

35th Fighter Group

35th Fighter Group

Constituted as 35th Pursuit Group (Interceptor) on 22 Dec 1939. Activated on 1 Feb 1940. Trained with P-35, P-36, P-39, and P-40 aircraft. Two squadrons (21st and 34th) moved to the Philippines in Nov 1941. Headquarters and another squadron (70th) sailed for Manila on 5 Dec but because of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor they returned to the US where the squadron flew some patrols. Headquarters and the 70th squadron sailed for Australia on 12 Jan 1942. Three days later all the combat squadrons were relieved and three others, still in the US, were assigned. Headquarters reached Australia in Feb 1942 and moved on to India. Meanwhile the squadrons had moved from the US to Australia and were training for combat with P-39's. Headquarters was transferred back to Australia, without personnel and equipment, in May 1942.

Redesignated 35th Fighter Group. Served in combat with Fifth AF, operating successively from bases in Australia, New Guinea, Owi, Morotai, and the Philippines. First used P-38's and P-39's; equipped with P-47's late in 1943 and with P-51's in Mar 1945. Helped to halt the Japanese advance in Papua and took part in the Allied offensive that recovered the rest of New Guinea, flying protective patrols over Port Moresby, escorting bombers and transports, attacking Japanese airfields and supply lines, and providing cover for Allied landings. In 1944 began long-range missions against enemy airfields and installations in the southern Philippines, Halmahera, and Borneo, preparatory to the US invasion of the Philippines. Beginning in Jan 1945, operated in support of ground forces on Luzon. Also escorted bombers and completed some fighter sweeps to Formosa and China. Bombed and strafed railways and airfields in Kyushu and Korea after moving to Okinawa in Jun 1945. Moved to Japan in Oct 1945 and, as part of Far East Air Forces, trained, took part in maneuvers, and flew surveillance patrols over Honshu. Redesignated 35th Fighter-Interceptor Group in Jan 1950. Equipped with F-80's.

Entered combat in the Korean War in Jul 1950 and almost immediately began converting from F-80's to F-51's. Operated from bases in Japan and Korea in support of UN ground forces, bombing and strafing enemy supply lines, troop concentrations, and communications. Transferred without personnel and equipment to Japan in May 1951. Remanned and equipped with F-51's and F-80's. Provided air defense for Japan. Converted to F-86 aircraft in 1955.

Squadrons. 18th: 1940. 20th: 1940. 21st: 1940-1942. 34th: 1940-1942. 39th: 1942-. 40th: 1942-. 41st: 1942-. 70th: 1941-1942.

Stations. Moffett Field, Calif, 1 Feb 1940; Hamilton Field, Calif, 10 Sep 1940-5 Dec 1941 and 9 Dec 1941-12 Jan 1942; Brisbane, Australia, 1 Feb 1942; New Delhi, India, Mar 1942; Sydney, Australia, 4 May 1942; Port Moresby, New Guinea, 22 Jul 1942; Tsili Tsili, New Guinea, 15 Aug 1943; Nadzab, New Guinea, 5 Oct 1943; Gusap, New Guinea, 7 Feb 1944; Owi, Schouten Islands, 22 Jul 1944; More tai, 27 Sep 1944; Mangaldan, Luzon, c. 20 Jan 1945; Lingayen, Luzon, c. 10 Apr 1945; Clark Field, Luzon, 19 Apr 1945; Okinawa, 28 Jun 1945; Irumagawa, Japan, Oct 1945; Yokota, Japan, 16 Mar 1950; Ashiya, Japan, 8 Jul 1950; Pohang, Korea, 14 Jul 1950; Tsuiki, Japan, 13 Aug 1950; Pohang, Korea, 3 Oct 1950; Yonpo, Korea, 18 Nov 1950; Pusan, Korea, c. 3 Dec 1950; Johnson AB, Japan, 25 May 1951; Yokota, Japan, 14 Aug 1954-.

Commanders. Maj O R Strickland, 1940; Col George P Tourtellot, 1940-unkn; Col Richard A Legg, 12 Mar 1942; Lt Col Malcolm A Moore, 26 Jul 1943; Lt Col Edwin A Doss, 23 Oct 1943; Lt Col Furlo S Wagner, 12 Feb 1944; Col Edwin A Doss, 4 May 1944; Col Harney Estes Jr, 27 Jul 1945; Col Raymond P Todd, 22 Mar 1946; Lt Col Richard D Dick, c. 13 Sep 1946; Col James R Gunn Jr, c. 11 Feb 1947; Col Ford Lauer, 28 Apr 1947; Col Ray W Clifton, 1 Sep 1947; Col Edgar M Scattergood Jr, 21 Jun 1948; Lt Col Bert W Marshall Jr, Aug 1948; Lt Col Archie M Burke, 13 May 1949; Lt Col Jack D Dale Jr, Nov 1949; Col William P McBride, 22 Feb 1951; Lt Col Homer M Cox, May 1951; Col John C Habecker, 25 Jun 1951; Col John R Propst, 6 Jun 1952; Lt Col Albert S Aiken, Feb 1955; Col Maurice L Martin, Jun 1955; Col Raymond M Gehrig, Aug 1955-.

Campaigns. World War II: East Indies; Air Offensive, Japan; China Defensive; Papua; New Guinea; Bismarck Archipelago; Western Pacific; Leyte; Luzon; Ryukyus; China Offensive. Korean War: UN Defensive; UN Offensive; CCF Intervention; 1st UN Counteroffensive; CCF Spring Offensive.

Decorations. Distinguished Unit Citation: Papua, 23 Jul 1942-23 Jan 1943. Philippine Presidential Unit Citation. Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation: 7 Sep 1950-7 Feb 1951.

Insigne Shield: Azure, a dexter cubit arm or grasping a dagger point to base gules. Motto: Attack To Defend (Approved 21 Feb 1941.)

347th Fighter Group

Constituted as 347th Fighter Group on 29 Sep 1942. Activated in New Caledonia on 3 Oct 1942. Detachments of the group, which was assigned to Thirteenth AF in Jan 1943, were sent to Guadalcanal, where they used P-39 and P-400 aircraft to fly protective patrols, support ground forces, and attack Japanese shipping. When the Allied campaign to recover the central and northern Solomons began in Feb 1943, the detachments, still operating from Guadalcanal and using P-38 and P-39 aircraft, escorted bombers and attacked enemy bases on New Georgia, the Russell Islands and Bougainville. Headquarters moved up from New Caledonia at the end of 1943; and the following month the group moved from Guadalcanal to Stirling Island to support ground forces on Bougainville, assist in neutralizing enemy bases at Rabaul, and fly patrol and search missions in the northern Solomons. Moved to New Guinea in Aug 1944. Equipped completely with P-38's. Escorted bombers to oil refineries on Borneo; bombed and strafed airfields and installations on Ceram, Amboina, Boeroe, Celebes, and Halmahera. Received a DUC for a series of long-range bombing and strafing raids, conducted through intense flak and fighter defense, on the airfield and shipping at Makassar, Celebes, in Nov 1944. Moved to the Philippines in Feb 1945. Supported landings on Mindanao in Mar 1945: bombed and strafed enemy installations and supported Australian forces on Borneo, attacked Japanese positions in northern Luzon, and flew escort missions to the Asiatic mainland. Moved to the US in Dec 1945. Inactivated on 1 Jan 1946.

Redesignated 347th Fighter Group (All Weather). Activated in Japan on 20 Feb 1947. Assigned to Far East Air Forces. Equipped with F-61's and later with F-82's. Inactivated on 24 Jun 1950.

4th FS - 67th FS - 68th FS - 70th FS - 339th FS

Squadrons. 4th: 1947-1950. 67th: 1942-1945. 68th: 1942-1945; 1947-1950. 70th: 1942-1943, 1945. 339th: 1942-1946; 1947-1950.

Stations. New Caledonia, 3 Oct 1942; Guadalcanal, 29 Dec 1943; Stirling, Treasury Islands, 15 Jan 1944; Sansapor, New Guinea, 15 Aug 1944; Middleburg, New Guinea, 19 Sep 1944; San Jose, Mindoro, 22 Feb 1945; Puerto Princesa, Palawan, 6 Mar-Dec 1945; Camp Stoneman, Calif, 30 Dec 1945-1 Jan 1946. Nagoya, Japan, 20 Feb 1947; Itazuke, Japan, 25 Sep 1947; Bofu, Japan, 15 Oct 1948; Ashiya, Japan, 6 May 1949; Nagoya, Japan, 1 Apr-24 Jun 1950.

Commanders. Lt Col George M McNeese, 3 Oct 1942; Col Leo F Dusard Jr, Jan 1944; Lt Col Leonard Shapiro, 25 Jun 1945-unkn. Unkn, Feb 1947-Aug 1948; Maj Elmer G DaRosa, Aug 1948; Maj Alden E West, Sep 1948; Lt Col John L McGinn, Oct 1948-unkn; Lt Col Clyde A Thompson, unkn-Jun 1950.

Campaigns. China Defensive; Guadalcanal; New Guinea; Northern Solomons; Bismarck Archipelago; Western Pacific; Leyte; Luzon; Southern Philippines; China Offensive.

Decorations. Distinguished Unit Citation: Netherlands East Indies, 7, 20, and 22 Nov 1944. Philippine Presidential Unit Citation.

Insigne. None.

348th Fighter Group

Constituted as 348th Fighter Group on 24 Sep 1942 and activated on 30 Sep. Prepared for combat with P-47's. Moved to the Southwest Pacific, May-Jun 1943, and assigned to Fifth AF. Operated from New Guinea and Noemfoor until Nov 1944. Flew patrol and reconnaissance missions and escorted bombers to targets in New Guinea and New Britain. Col Neel E Kearby was awarded the Medal of Honor for action over New Guinea on 11 Oct 1943: after leading a flight of four fighters to reconnoiter the enemy base at Wewak, Col Kearby sighted a Japanese bomber formation escorted by more than 30 fighters; despite the heavy odds and a low fuel supply, and although his mission had been accomplished, Kearby ordered an attack, personally destroying six of the enemy planes. For covering Allied landings and supporting ground forces on New Britain, 16-31 Dec 1943, the group was awarded a DUC. In 1944 began to attack airfields, installations, and shipping in western New Guinea, Ceram, and Halmahera to aid in neutralizing those areas preparatory to the US invasion of the Philippines. After moving to the Philippines in Nov 1944, provided cover for convoys, flew patrols, escorted bombers, attacked enemy airfields, and supported ground forces. Received a DUC for withstanding assaults by enemy fighters to cover bombers raiding Clark Field on 24 Dec 1944. Also attacked shipping along the China coast and escorted bombers to Formosa and the Asiatic mainland. Moved to the Ryukyus in Jul 1945 and completed some escort and attack missions to Kyushu before the war ended. Moved to Japan in Oct 1945 as part of Far East Air Forces. Inactivated on 10 May 1946.

Redesignated 108th Fighter Group. Allotted to ANG (NJ) on 24 May 1946. Extended federal recognition on 16 Oct 1946. Called to active duty on 1 Mar 1951. Redesignated 108th Fighter-Bomber Group. Assigned first to Strategic Air Command and later to Tactical Air Command. Equipped with F-47's. Relieved from active service on 1 Dec 1952 and returned to the control of ANG (NJ).

460th Fighter Squadron

Squadrons. 149th: 1951-1952. 153d 1951-1952. 340th: 1942-1946. 341st (later 141st): 1942-1946; 1951-1952. 342d: 1942-1946. 460th: 1944-1946.

Stations. Mitchel Field, NY, 30 Sep 1942; Bradley Field, Conn, 4 Oct 1942; Westover Field, Mass, 29 Oct 1942; Providence, RI, c. 3 Jan 1943; Westover Field, Mass, 28 Apr-9 May 1943; Port Moresby, New Guinea, 23 Jun 1943; Finschhafen, New Guinea, 16 Dec 1943; Saidor, New Guinea, 29 Mar 1944; Wakde, 22 May 1944; Noemfoor, 26 Aug 1944; Leyte, 16 Nov 1944; San Marcelino, Luzon, 4 Feb 1945; Floridablanca, Luzon, 15 May 1945; Ie Shima, 9 Jul 1945; Itami, Japan, Oct 1945-10 May 1946. Newark Mun Aprt, NJ, 1 Mar 1951; Turner AFB, Ga, 14 Mar 1951; Godman AFB, Ky, 9 Dec 1951-1 Dec 1952.

Commanders. Col Neel E Kearby, Oct 1942; Col Robert R Rowland, 17 Nov 1943; Lt Col William M Banks, 8 Jun 1945; Maj Walter G Benz, 26 Nov 1945-unkn. Maj J D Zink, Mar 1951; Col Alvan C Gillem II, Jun 1951; Col Carl W Stapleton, c. Nov 1951; Col Donald J Strait, 14 Jan 1952; Col George Laven Jr, 4 Aug-1 Dec 1952.

Campaigns. Air Offensive, Japan; China Defensive; New Guinea; Bismarck Archipelago; Western Pacific; Leyte; Luzon; China Offensive.

Decorations. Distinguished Unit Citations: New Britain, 16-31 Dec 1943; Philippine Islands, 24 Dec 1944. Philippine Presidential Unit Citation

Insigne Shield: Azure, within a bordure dimidiated, gules, hand gauntleted in armour proper, encircled with wreath of laurel, vert, grasping a torch argent, flamant proper. Motto: Per Caelum Victoriae - Through the Skies to Victory. (Approved 15 Aug 1951.)

Pacific Theater Operations - 5AF

The Fifth Air Force (5 AF) is a numbered air force of the United States Air Force Pacific Air Forces (PACAF). It is headquartered at Yokota Air Base, Japan. It is the U.S. Air Force's oldest continuously serving Numbered Air Force. The organization has provided 80 years of continuous air power to the Pacific since its establishment in September 1941.

Fifth Air Force is the Headquarters Pacific Air Forces forward element in Japan, and maximizes partnership capabilities and promotes bilateral defense cooperation. In addition, 5 AF is the air component to United States Forces Japan.

Its mission is three-fold. First, it plans, conducts, controls, and coordinates air operations assigned by the PACAF Commander. Fifth Air Force maintains a level of readiness necessary for successful completion of directed military operations. And last, but certainly not least, Fifth Air Force assists in the mutual defense of Japan and enhances regional stability by planning, exercising, and executing joint air operations in partnership with Japan. To achieve this mission, Fifth Air Force maintains its deterrent force posture to protect both U.S. and Japanese interests, and conducts appropriate air operations should deterrence fail.

History

Fourteen Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses that survived the Battle of the Philippines left Mindanao for Darwin, Australia, between 17 and 20 December 1941, the only aircraft of the Far East Air Force to escape. After its evacuation from the Philippines on 24 December 1941, FEAF headquarters moved to Australia and was reorganized and redesignated 5 Air Force on 5 February 1942, with most of its combat aircraft based on fields on Java. It seemed at the time that the Japanese were advancing just about everywhere. The remaining heavy bombers of the 19th Bombardment Group, based at Malang on Java, flew missions against the Japanese in an attempt to stop their advance. They were joined in January and February, two or three at a time, by 37 B-17Es and 12 LB-30s of the 7th Bombardment Group. The small force of bombers, never numbering more than 20 operational at any time, could do little to prevent the invasion of the Netherlands East Indies, launching valiant but futile attacks against the masses of Japanese shipping, with six lost in combat, six in accidents, and 26 destroyed on the ground.

The 7th Bombardment Group was withdrawn to India in March 1942, leaving the 19th to carry on as the only B-17 Fortress-equipped group in the South Pacific. About this time it was decided that replacement B-17s would not be sent to the southwest Pacific, but be sent exclusively to the Eighth Air Force which was building up in England. By May, Fifth Air Force's surviving personnel and aircraft were detached to other commands and the headquarters remained unmanned for several months, but elements played a small part in the Battle of the Coral Sea (7–8 May 1942) when the 435th Bomb Squadron of the 19th Bomb Group saw the Japanese fleet gathering in Rabaul area nearly two weeks before the battle actually took place. Because of the reconnaissance activity of the 435th Bomb Squadron, the US Navy was prepared to cope adequately with the situation. The squadron was commended by the US Navy for its valuable assistance not only for its excellent reconnaissance work but for the part played in the battle.

Headquarters Fifth Air Force was re-staffed at Brisbane, Australia on 18 September 1942 and placed under the command of Major General George Kenney. United States Army Air Forces units in Australia, including Fifth Air Force, were eventually reinforced and re-organised following their initial defeats in the Philippines and the East Indies. At the time that Kenney had arrived, Fifth Air Force was equipped with three fighter groups and five bombardment groups.

Fighter Groups:

8th FG (P-39) Townsville, Australia

35th FG (P-40) Port Moresby, New Guinea

49th FG (P-40) Darwin, Australia

Bomber Groups:

3rd BG (B-25, A-20, & A-24) Charters Towers, Australia

19th BG (Non-Operational. Battle scarred from Philippines & Java) Mareeba, Australia

22nd BG (B-26) Woodstock, Australia

38th BG (B-25) Charters Towers, Australia

43rd BG (B-17 until 1943; B-24 1943–1945) Port Moresby, New Guinea

In addition, Fifth Air Force controlled two transport squadrons and one photographic squadron comprising 1,602 officers and 18,116 men.

Kenney was later appointed commander of Allied air forces in the South West Pacific Area, reporting directly to General Douglas MacArthur. Under Kenney's leadership, the Fifth Air Force and Royal Australian Air Force provided the aerial spearhead for MacArthur's island hopping campaign.

US Far East Air Forces

On 4 November 1942, the Fifth Air Force commenced sustained action against the Japanese in Papua New Guinea and was a key component of the New Guinea campaign (1942–1945). Fifth Air Force engaged the Japanese again in the Philippines campaign (1944–45) as well as in the Battle of Okinawa (1945).

Fifth Air Force along with Thirteenth Air Force in the Central Pacific and Seventh Air Force in Hawaii were assigned to the newly created United States Far East Air Forces (FEAF) on 3 August 1944. FEAF was subordinate to the U.S. Army Forces Far East and served as the headquarters of Allied Air Forces Southwest Pacific Area. By 1945, the three numbered air forces were supporting operations throughout the Pacific. FEAF was the functional equivalent in the Pacific of the United States Strategic Air Forces (USSTAF) in the European Theater of Operations.

Order of battle, 1945

5AF Order of battle, 1945V Fighter Command Night Fighter Units V Bomber Command Photo Reconnaissance 54th Troop Carrier Wing 3d ACG (P-51, C-47) 418th NFS 3d BG (L) (B-25, A-20) 6th RG (F-5, F-7) 2d CCG 8th FG (P-40, P-38) 421st NFS 22d BG (M/H) (B-26 – B-24) 71st RG (B-25) 317th TCG 35th FG (P-47, P-51) 547th NFS 38th BG (M) (B-25) 374th TCG (1943 only) 49th FG (P-40, P-47, P-38) 43d BG (H) (B-24) 375th TCG 58th FG (P-47) 90th BG (H) (B-24) 433d TCG 348th FG (P-47, P-51) 312th BG (L) (A-20) 475th FG (P-38) 345th BG (M) (B-25) 380th BG (H) (B-24) 417th BG (L) (A-20) LEGEND: ACG – Air Commando Group, FG – Fighter Group, NFS – Night Fighter Squadron, BG (L) – Light Bomb Group, BG (M) – Medium Bomb Group, BG (H) – Heavy Bomb Group, RG – Reconnaissance Group, CCG – Combat Cargo Group, TCG – Troop Carrier Group

When the war ended, Fifth Air Force had an unmatched record of 3,445 aerial victories, led by the nation's two top fighter aces Major Richard Bong and Major Thomas McGuire, with 40 and 38 confirmed victories respectively, and two of Fifth Air Force's ten Medal of Honor recipients.

Shortly after World War II ended in August, Fifth Air Force relocated to Irumagawa Air Base, Japan, about 25 September 1945 as part of the Allied occupation forces. The command remained in Japan until 1 December 1950 performing occupation duties.

Korean War

In 1950, Fifth Air Force was called upon again, becoming the main United Nations Command combat air command during the Korean War, and assisted in bringing about the Korean Armistice Agreement that formally ended the war in 1953.

In the early morning hours of 25 June, North Korea launched a sudden, all-out attack against the south. Reacting quickly to the invasion, Fifth Air Force units provided air cover over the skies of Seoul. The command transferred to Seoul on 1 December 1950, remaining in South Korea until 1 September 1954.

In this first Jet War, units assigned to the Fifth Air Force racked up an unprecedented 14.5 to 1 victory ratio. By the time the truce was signed in 1953, Fifth Air Force had flown over 625,000 missions, downing 953 North Korean and Chinese aircraft, while close air support accounted for 47 percent of all enemy troop casualties.

Thirty-eight fighter pilots were identified as aces, including Lieutenant Colonel James Jabara, America's first jet ace; and Captain Joseph McConnell, the leading Korean War ace with 16 confirmed victories. Additionally, four Medals of Honor were awarded to Fifth Air Force members. One other pilot of note was Marine Major John Glenn, who flew for Fifth Air Force as part of an exchange program.

With the end of combat in Korea, Fifth Air Force returned to normal peacetime readiness Japan in 1954.

Cold War

Not only concerned with maintaining a strong tactical posture for the defense of both Japan and South Korea, Fifth Air Force played a critical role in helping the establishment of the Japan Air Self-Defense Force as well as the Republic of Korea Air Force. These and other peacetime efforts lasted a decade before war clouds once again developed in the Pacific.

This time, the area of concern was Southeast Asia, beginning in 1964 with the Gulf of Tonkin Crisis. Fifth Air Force furnished aircraft, aircrews, Support personnel, and supplies throughout the eight years of combat operations in South Vietnam and Laos. Since 1972, the Pacific has seen relative calm, but that doesn't mean Fifth Air Force hasn't been active in other roles. The command has played active or supporting roles in a variety of issues ranging from being first on the scene at the Korean Air Lines Flight 007 shoot down in 1983 to deploying personnel and supplies for the Persian Gulf War in 1990.

During this time span, the size of Fifth Air Force changed as well. With the activation of Seventh Air Force in 1986, fifth left the Korean Peninsula and focused its energy on continuing the growing bilateral relationship with Japan.

The Fifth Air Force's efforts also go beyond combat operations. Fifth Air force has reacted to natural disasters in Japan and abroad. These efforts include the Great Hanshin earthquake in 1995 and Super Typhoon Paka which hit Guam in 1997. Fifth Air Force has reached out to provide assistance to victims of floods, typhoons, volcanoes, and earthquakes throughout the region.

The 432d Tactical Fighter Wing flew F-16s from Misawa Air Base from July 1, 1984 – October 31, 1994. On the inactivation of the wing, its personnel, aircraft, and other assets were used to reform the 35th Fighter Wing.

Present Day

Today, according to the organization's website, major components include the 18th Wing, Kadena Air Base, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan; the 35th Fighter Wing at Misawa Air Base, and the 374th Airlift Wing at Yokota Air Base. Kadena AB hosts the 18th Wing, the largest combat wing in the USAF. The Wing includes F-15 fighters, KC-135 refuelers, E-3 Airborne Warning and Control System aircraft, and HH-60G Pave Hawk rescue helicopters, and represents a major combat presence and capability in the Western Pacific. The 35th Fighter Wing, Misawa Air Base, Japan, includes two squadrons equipped with the most modern Block 50 F-16 variant, dedicated to the suppression of enemy air defenses. The final formation is the 374th Airlift Wing, at Yokota Air Base, Japan.

According to a 2017 study by two US Navy commanders, in case of a surprise Chinese ballistic missile attack against airbases in Japan, more than 200 U.S. aircraft would be trapped or destroyed on the ground in the first hours of the conflict.

Lineage, assignments, stations, and components

Lineage

Established as Philippine Department Air Force on 16 August 1941

Activated on 20 September 1941

Redesignated: Far East Air Force on 16 November 1941

Redesignated: 5 Air Force on 5 February 1942

Redesignated: Fifth Air Force* on 18 September 1942.

Fifth Air Force is not to be confused with a second "Fifth" air force created as a temporary establishment to handle combat operations after the outbreak of hostilities on 25 June 1950, in Korea. This numbered air force was established as Fifth Air Force, Advance, and organized at Itazuki AB, Japan, assigned to Fifth Air Force, on 14 July 1950. It moved to Taegu AB, South Korea, on 24 July 1950, and was redesignated Fifth Air Force in Korea at the same time. After moving, it apparently received command control from U.S. Far East Air Forces. The establishment operated from Pusan, Taegu, and Seoul before being discontinued on 1 December 1950.

Commands

V Air Force Service: 18 June 1943 – 15 June 1944

V Air Service Area: 9 January 1944 – 15 June 1944

5 Bomber (later, V Bomber): 14 November 1941 – 31 May 1946

V Fighter: 25 August 1942 – 31 May 1946

5 Interceptor: 4 November 1941 – 6 April 1942

Became Army Air Force Infantry unit during Battle of the Philippines (1941–42) (20 December 1941 – 9 April 1942)

Far East Air Service (later, 5 Air Force Base; V Air Force Base): 28 October 1941 – 2 November 1942

Divisions

39th Air Division: 1 September 1954 – 15 January 1968

41st Air Division: 1 September 1954 – 15 January 1968

43d Air Division: 1 September 1954 – 1 October 1957

313th Air Division: 1 March 1955 – 1 October 1991

314th Air Division: 31 May 1946 – 1 March 1950; 1 December 1950 – 18 May 1951; 15 March 1955 – 8 September 1986

315 Air Division (formerly, 315 Composite Wing): 1 June 1946 – 1 March 1950.

Wings

8th Fighter Wing, later 8th Tactical Fighter Wing, 1950s

18th Wing: 1 Oct 1991-.

35th Fighter Wing: 1 Oct 1994-.

51st Fighter Wing: 1955-September 1986

374th Airlift Wing: 1 Apr 1992-.

432d Tactical Fighter Wing, Misawa Air Base, Japan: July 1, 1984 – May 31, 1991; 432d Fighter Wing from June 1, 1991 - October 31, 1994 (wing personnel and assets thereafter used to reactivate 35th Fighter Wing)

6100th Support Wing, Tachikawa Air Base, Japan: "Brigadier General Thomas R. FORD Replaced Col. Lewis B. MENG as commander of 6100th Support Wing effective" 11 June 1962. "6100 Support Wing was Major Air Command control (MAJCON) unit directly subordinate to Headquarters (HQ) 5 Air Force. Contains.. functions of various subordinate elements of 6100 Support Wing (Kanto Base Command)."

Groups

2nd Combat Cargo Group: October 1944-15 January 1946

Assignments

Philippine Department, U.S. Army, 20 September 1941

US Forces in Australia (USFIA), 23 December 1941

Redesignated: US Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA), 5 January 1942

American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM), 23 February 1942

Allied Air Force, Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA), 2 November 1942

Far East Air Forces (Provisional), 15 June 1944

Far East Air Forces, 3 August 1944

Redesignated: Pacific Air Command, United States Army, 6 December 1945

Redesignated: Far East Air Forces, 1 January 1947

Redesignated Pacific Air Forces, 1 July 1957—present

Stations

Nichols Field, Luzon, 20 September 1941

RAAF Base Darwin, Australia, 31 December 1941

Bandoeng, Java, 18 January 1942

Brisbane AAB, Australia,c 1 March 1942

Nadzab Airfield, New Guinea, 15 June 1944

Owi Airfield, Schouten Islands, Netherlands East Indies, 10 August 1944

Bayug Airfield, Leyte, Philippines, c. 20 November 1944

McGuire Field, Mindoro, Philippines, January 1945

Clark Field, Luzon, Philippines, April 1945

Hamasaki (Motobu Airfield), Okinawa, 4 August 1945

Irumagawa AB, Japan, c. 25 September 1945

Tokyo, Japan, 13 January 1946

Nagoya, Japan, 20 May 1946

Seoul AB (K-16), Korea, 1 December 1950

Taegu AB (K-2), Korea, 22 December 1950

Seoul AB (K-16), 15 June 1951

Osan AB, Korea, 25 January 1954

Nagoya AB (later, Nagoya AS; Moriyama AS), Japan, 1 September 1954

Fuchu AS, Japan, 1 July 1957

Yokota AB, Japan, 11 November 1974–present

5th Air Force (5th AF) "Forgotten Fifth" U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF)

The 5th Air Force (5th AF) was part of the U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF). On February 5, 1942 the prewar Far East Air Force (FEAF) was redesignated the 5th Air Force (5th AF) in Australia. Also known as the Fifth Air Force (Fifth AF) or V Air Force (V AF). Unofficially dubbed the "Forgotten Fifth" as forgotten in the South West Pacific Area (SWPA) at the end of the supply chain.

On September 3, 1942 the 5th Air Force (5th AF) was assigned to Major General George C. Kenney becomes Commanding Officer (C.O.) with its Headquarters in Brisbane and retains command of the Allied Air Forces in the Southwest Pacific. On October 15, 1942 promoted to the rank of Lieutenant General and was the the highest ranking officer under General Douglas MacArthur.

As the leader of the 5th Air Force, Kenney fought an innovative and creative war against the Japanese using available aircraft and weapons effectively. Officers under his command created strafer variants of aircraft adding forward firing extra machine guns to the nose of A-20 Havocs and B-25 Mitchells. The 5th Air Force used ordnance including the daisy cutter (wire wrapped bombs) and parachute-retarded fragmentation bomb (parafrag bomb) that were suited for destroying parked aircraft and inflicting damage in jungle areas. Officers under his command pioneered "skip bombing" flying bombers at low level to skip bombs off the surface of the sea to hit an enemy ship instead of ineffective high altitude bombing runs that allowed the target to maneuver away once bombs were released.

On June 15, 1944 the Far East Air Force (FEAF) was reformed and combined the 5th Air Force (5th AF) in the South West Pacific Area (SWPA) and 13th Air Force (13th AF) in the South Pacific (SOPAC) under the command of General George C. Kenney. The FEAF continues until the end of the Pacific War.

Fighter Group (FG)

8th Fighter Group (8th FG) "Cyclone's Flying Circus"

35th Fighter Group (35th FG)

49th Fighter Group (49th FG)

58th Fighter Group (58th FG)

347th Fighter Group (347th FG)

348th Fighter Group (348th FG)

475th Fighter Group (475th FG) "Satan's Angels"Bombardment Group (BG)

3rd Bombardment Group (3rd BG) "The Grim Reapers"

19th Bombardment Group (19th BG)

22nd Bombardment Group (22nd BG) "Red Raiders"

38th Bombardment Group (38th BG) "Sun Setters"

43rd Bombardment Group (43rd BG) "Ken's Men"

90th Bombardment Group (90th BG) "Jolly Rogers"

312th Bombardment Group (312th BG) "Roarin' 20's"

345th Bombardment Group (345th BG) "Air Apaches"

380th Bombardment Group (380th BG) "Flying Circus"

417th Bombardment Group (417th BG) "Sky Lancers"hotographic Reconnaissance Group (PRG)

6th Photographic Reconnaissance Group (6th PRG)

Tactical Reconnaissance Group (PRG)

71st Tactical Reconnaissance Group (71st TRG)

Night Fighter Squadron (NFS)

418th Night Fighter Squadron (418th NFS)

421st Night Fighter Squadron (421st NFS)Troop Carrier Wing (TCW)

54th Troop Carrier Wing (54th TCW)

Troop Carrier Group (TCG)

63rd Troop Carrier Group (63rd TCG)

317th Troop Carrier Group (317th TCG)

374th Troop Carrier Group (374th TCG)

375th Troop Carrier Group (375th TCG)

433rd Troop Carrier Group (433rd TCG)Service Group (SG)

Far East Air Force - Combat Replacement Training Center (FEAF-CRTC, 360th Service Group, 8th Service Group)

Commanding Officers (C.O.)

Lt. General George C. Kenney

source: https://pacificwrecks.com/units/usaaf/5af/index.html

Thirteenth Air Force

Formed on December 14, 1942. Operated primarily in South Pacific Area (SPA) of the Pacific Theater of Operations (PTO)

5th Bombardment Group

Unit formed in 1915. Large number of B-18s and B-17C/Ds destroyed during Pearl Harbor Attack. Surviving B-17s sent to New Hebrides in 1942. Re-equipped in Hawaii with B-24s and redeployed in August 1943. Stationed in Solomon Islands, Admiralty Islands, Netherlands East Indies, Schouten Islands, Molucca Islands, Philippines. Transitioned to RB-29s in 1946.

23d Bombardment Squadron

31st Bombardment Squadron

72d Bombardment Squadron

394th Bombardment Squadron

307th Bombardment Group

Established with B-17s in April 1942; transitioned to B-24s at Hickam Field, November 1942. Stationed in Solomon Islands, Admiralty Islands, Netherlands East Indies, Philippines. Transitioned to B-29s in 1946

370th Bombardment Squadron

371st Bombardment Squadron

372d Bombardment Squadron

424th Bombardment Squadron

4th Reconnaissance Group

Constituted as 4th Photographic Group on 14 Jul 1942 and activated on 23 Jul. Trained for overseas duty with F-4's. Moved to the South Pacific late in 1942. Assigned to Thirteenth AF in Jan 1943. Redesignated 4th Photographic Reconnaissance and Mapping Group in May 1943, 4th Photographic Group (Reconnaissance) in Nov 1943, and 4th Reconnaissance Group in May 1945. From Dec 1942 to May 1945 the group, based successively on New Caledonia, Espiritu Santo, Guadalcanal, and Morotai, flew reconnaissance missions over enemy territory to supply air force units with target and damage assessment photographs and to provide army and navy units with intelligence on Japanese troop concentrations, installations, shore defenses, supply routes, and shipping. It also produced maps of Allied and enemy-held territory and prepared navigation charts for US units. During the last three months of the war the group photographed Japanese positions and installations on Mindanao and Borneo to aid US and Australian operations. Moved to Leyte in Sep 1945. Inactivated on 15 Jan 1946. Disbanded on 6 Mar 1947.

17th Combat Mapping Squadron

18th Combat Mapping Squadron

19th Combat Mapping Squadron

20th Combat Mapping Squadron

38th Combat Mapping Squadron

Squadrons. 17th: 1942-1946. 18th: 1942-1944. 19th: 1942-1943. 20th: 1942-1943. 38th: 1945-1946.

Stations. Colorado Springs, Colo, 23 Jul-24 Oct 1942; New Caledonia, 22 Nov 1942; Espiritu Santo, 22 Jan 1943; Guadalcanal, 6 May 1944; Morotai, 12 Dec 1944; Leyte, Sep 1945-15 Jan 1946.

Commanders. 2nd Lt Everett E Shaw, 23 Jul 1942; Lt Col Francis L Rivard, 10 Aug 1942; Lt Col Charles P Hollstein, 3 Sep 1942; Col Paul C Schauer, 18 Jul 1943; Lt Col Hillford R Wallace, 7 Jun 1944; Maj Sidney L Hardin, 4 Aug 1944; Lt Col Hershell E Parsons, 20 Jan 1945-unkn.

Campaigns. Guadalcanal; New Guinea; Northern Solomons; Bismarck Archipelago; Western Pacific; Leyte; Southern Philippines.

Decorations. Philippine Presidential Unit Citation.

Insigne Shield: Azure, three piles and three like ordinaries transposed conjoined in honor point or. (Approved 28 Nov 1942.)

868th Bombardment Squadron

Established in July 1943 with SB-24 RADAR aircraft; assigned directly to 13th AF Headquarters. Flew low level, anti-shipping strikes under the cover of darkness. Also flew as pathfinders for high-altitude bombers. Special missions were flown against land targets at night and one of the intentions was to prevent the Japanese from sleeping. Stationed in Solomon Islands, Admiralty Islands, Schouten Islands, Netherlands East Indies, Philippines, Okinawa. Inactivated December 1945

The Thirteenth Air Force

HENDERSON FIELD had been won in the violent air, sea,and land battles which had occurred in the hectic days of October and November. There would be more fighting on Guadalcanal, more battles at sea in the Slot, many more in the air, too, but henceforth there would be far less doubt as to the outcome. In October and November there had been little margin for error or miscalculation. The race had been far too close for comfort. But now from November forward, the Allied potential began to show under the energetic leadership of Admiral Halsey; men, ships, guns, and planes reached Guadalcanal in numbers sufficient to provide a modest margin of safety.

When the smoke had cleared away and the pressure had eased somewhat, the men who sent the planes on their missions took stock of their weapons. By the end of November, General Harmon's heavy bombers had been in operation four full months. They had gone out from Espiritu Santo almost daily, staging through Guadalcanal as often as possible, and now their commanders and aircrews had gathered sufficient operational data to permit an assessment of their achievements and an analysis of the employment of heavy bombardment aviation in the theater. Of 610 of all types of Japanese planes contacted, B-17 gunners had claimed twenty-one aircraft destroyed and fifty-seven damaged. On the debit side, twenty-one bombers had been lost while executing their missions, but more than half this number could be attributed to operational losses. No more than six could be recorded as combat losses, excluding the three additional planes which were badly damaged by naval gunfire while parked on Henderson Field. Altogether these aircraft had carried down with them a total of 101 officers and men of the 5th and 11th Groups, of which number a third could be charged to operational causes rather than to combat with the enemy.

Pilots, crews, and commanders had learned many lessons during the first sixteen weeks of continuous operations. There was complete confidence in the B-17 as a combat weapon; antiaircraft fire repeatedly had hurt the bombers, and so had the 7.7-mm. machine guns and 20-mm. cannon of the Japanese Zeros, but the toughness of the B-17 had enabled most of the planes to return to their bases. They were highly durable and pilots respected them. That this toughness would be needed was evident from a marked improvement in enemy fighter tactics since the initial contacts in July and August. Zero pilots always fought more aggressively over their own bases, and it was believed that fresh pilots with considerable experience were reaching the Solomons from other fronts.

Certainly, the B-17 crews were having trouble in meeting effectively the frontal attack so often employed by the Zero pilots. To combat this menace General Harmon had requested, as early as 31 August, modification of all 11th Group B-17's after the pattern completed on one of his heavy bombers by the Cheyenne Modification Center. This operation involved the installation of two .50-cal. nose guns and another in the radio compartment, together with new mounts for the waist guns and larger waist ammunition boxes to provide flexible feed. Initial experience with these improvements had shown a material contribution to the defense of the B-17 against frontal attack, but the field of fire still remained badly restricted and it was doubted that anything short of a nose turret would solve the problem.

Colonel Saunders in his own analysis cited the toughness and aggressiveness of the fighter unit encountered over Buin, where enemy fighters seemed much more difficult to shoot down, indicating the presence of armor in the planes. He granted the need for a nose power turret and for installation of armor plate in the entire nose compartment.

Had his B-17's been so equipped, several bombardiers and navigators would not have been killed, but beyond this, his observations of operations and enemy tactics in the South Pacific indicated that the time had come for a radical change in the design of heavy bombers. The B-17, he felt, had been developed to the extreme limit, and now a completely new aircraft should be built.

Nevertheless, only two aircraft were known to have been lost to enemy fighters, one on 24 September over Buin and the other on 18 November after a running fight of seventy miles. Thus far, and in most cases, formations of three or more B-17's had proved sufficiently strong to prevent serious damage at the hands of enemy fighters.

If the record of the heavy bombers against enemy aircraft was outstanding, the statistics turned in by Saunders' aircrews indicated quite a different performance against enemy ships. Since 31 July a total of 1,163 surface craft of all types had been contacted, of which 60 were attacked with a total of 828 bombs. Of this number, the pilots claimed 4 sunk and 15 damaged, exclusive of 9 others believed damaged as a result of close misses.

General Harmon had presented to Admiral Halsey on 22 October a statistical analysis of the effect of search activities upon the striking power of the B-17's, concluding that on a basis of eight planes flying daily search missions, each of eleven hours' duration, approximately 78 per cent of the group's total effort was devoted to reconnaissance work. The remaining 22 per cent of flying time was available for strike missions. Harmon conceded that this view of the problem was somewhat academic, but nevertheless he believed it emphasized the necessity for preserving the offensive effort of the bombers. He accordingly had recommended that no more than 25 per cent of the heavy bomber effort should be expended thereafter on reconnaissance, that a careful survey be made of all equipment and its employment in order to secure a reduction of the current figure, and that Hudsons be placed in service to supplement the search effort of the PBY's and B-17's. As for targets, he recommended that the heavy bombers be concentrated upon important objectives lying beyond the range of other types of aircraft, or in force upon vital surface objectives at all ranges. But the planes should not be assigned definite strike missions against small detachments of cruisers and destroyers at long range because of the improbability of obtaining hits on such highly maneuverable targets, except by employment of more planes than the target was worth.

On 20 November, Harmon submitted to COMSOPAC another extensive analysis of the difficulties confronting Colonel Saunders. He had discovered that the attacks by B-17's against the convoy on the 14th had resulted in no more than 1.1 per cent direct hits, which he viewed as less than a distinguished performance. The action of the following day had yielded a better score, since 12.5 per cent of the bombs dropped were hits, but the record was weakened somewhat in view of the fact that the hits had been made in part upon a beached transport or on a vessel lying motionless upon the surface of the sea. Of all bombs dropped against maneuvering enemy surface craft during the early months of the campaign, slightly less than 1 per cent was classified as hits, although the inclusion of those listed as probable hits would bring the figure up to 2.5 per cent.

Colonel Saunders was fully aware of his chief's reaction to the results thus far obtained. Early in November, Harmon had advised the 11th Group commander of the necessity of inflicting more damage upon the enemy if "we are to justify the type and volume of effort we are putting into our B-17 operations for long range strike against enemy surface objectives."He did not urge a prodigal expenditure of planes and crews, but in view of the remarkably light loss sustained from enemy fire, the planes must be prepared to bomb from dangerously low altitudes. It was a pressing matter. Vital enemy land installations at this stage of the war lay beyond the reach of any considerable bombing force, and it was only through his seaborne tentacles that the enemy could be hurt seriously. General Harmon was not prepared to accept the doctrine of skip bombing with 4-second fuzes, but he did feel that Saunders should be ready to employ the B-17's in this manner if the emergency should warrant action which might be sacrificial in nature.

Harmon offered his suggestion in a spirit of objective examination, in the hope that he and Saunders might advance the effectiveness of the air weapon against the Japanese. The tremendous handicaps under which the heavy bombers had operated from Espiritu Santo received full recognition, and Harmon assured Saunders that he had exerted his utmost effort to develop a suitable airfield on Guadalcanal.

Back in Washington, General Arnold had observed closely bomber operations in the South Pacific and he, too, was perturbed over the failure to strike in strength at surface targets during the great convoy action of mid-November, even though he expressed pride in the general performance of the heavy bombers.

The limitations which had contributed to the low score of the bombers were more apparent to the Army's airmen than to the theater commander, Admiral Halsey. Practically all targets had been at maximum range and the majority of them lay in excess of that range, thereby necessitating a reduction in the bomb load carried by the B-17's. Furthermore, the extreme length of the missions, coupled with frequent necessity for exhaustive search by striking forces to locate targets, necessarily induced crew fatigue and strain, which in turn exerted an unfortunate effect upon bombing accuracy. In Harmon's view, as he explained to Admiral Halsey, the power of bombardment stood in inverse ratio to the distance to the target.

In the Solomons operations, always it was the maneuverable surface craft which defied the bombardiers. Few of the latter had entered the area with much experience against this type of objective, and only rarely was it possible to assign specific targets to the aircrews in advance of the mission.

Even the choice of bomb load was sharply curtailed. During the first three months of operations there were only two fuze selections available-instantaneous and 1/10-second delay--of which the former was preferred because it would penetrate the water only some fifteen feet prior to detonation, thereby creating a mining effect in the case of near misses.

Perhaps most serious of all the problems was the tactical employment of the heavy bombers, a factor dictated by forces quite beyond the control either of General Harmon or the 11th Group commander. Colonel Saunders had gone out from Hawaii with bombing plans based upon attacks by nine planes-three flights of three planes each. Yet in practice he found that it was quite impossible to apply this technique; not enough planes could be put into the air to produce a pattern of nine bombers, nor were the experienced flight leaders available who could have effected perfect timing. Over and above the heavy claims upon his resources for search operations, the airdrome facilities at Espiritu Santo simply would not permit takeoffs in sufficient force-there were no circulating taxiways and there was no traffic control. Three months had passed before sufficient lumber arrived to permit erection of a control tower that extended up above the coconut trees. For these several reasons the air commanders felt reasonably satisfied if they could put six bombers together in the air.

It was pointed out to COMSOPAC that even in November clearance of twelve B-17's from Espiritu's bomber strip consumed one hour, while landing the same flight cost an additional hour and a half if it should return after dark, and obviously all this time must be deducted from the maximum flying time--and therefore range--of the formation.

It is of interest to note that shortly before the Battle of Midway, Maj. Gen. Robert C. Richardson in Hawaii informed the Chief of Staff that in order to achieve a mathematical probability of 7 per cent hits on a maneuvering Japanese carrier under ideal conditions and from 14,000 feet, a minimum force of eighteen to twenty bombers per carrier would be necessary. Anything less would produce only the most meager results.