Speed and altitude records

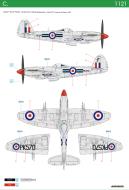

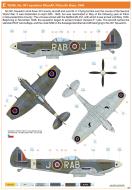

The Spitfire Mk XI flown by Sqn. Ldr. Martindale, seen here after its flight on 27 April 1944 during which it was damaged achieving a true airspeed of 606 mph (975 km/h or Mach 0.92)

Beginning in late 1943, high-speed diving trials were undertaken at Farnborough to investigate the handling characteristics of aircraft travelling at speeds near the sound barrier (i.e., the onset of compressibility effects). Because it had the highest limiting Mach number of any aircraft at that time, a Spitfire XI was chosen to take part in these trials. Due to the high altitudes necessary for these dives, a fully feathering Rotol propeller was fitted to prevent overspeeding. It was during these trials that EN409, flown by Squadron Leader J. R. Tobin, reached 606 mph (975 km/h) (Mach 0.891) in a 45° dive.

In April 1944, the same aircraft suffered engine failure in another dive while being flown by Squadron Leader Anthony F. Martindale, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR), when the propeller and reduction gear broke off. The dive put the aircraft to Mach 0.92, the fastest ever recorded in a piston-engined aircraft, but when the propeller came off the Spitfire, now tail-heavy, zoom-climbed back to altitude. Martindale blacked out under the 11 g loading, but when he resumed consciousness he found the aircraft at about 40,000 feet with its (originally straight) wings now slightly swept back.[123] Martindale successfully glided the Spitfire 20 mi (32 km) back to the airfield and landed safely.[124] Martindale was awarded the Air Force Cross for his exploits.[125]

RAE Bedford (RAE) modified a Spitfire for high-speed testing of the stabilator (then known as the 'flying tail') of the Miles M.52 supersonic research aircraft. RAE test pilot Eric Brown stated that he tested this successfully during October and November 1944, attaining Mach 0.86 in a dive.[126]

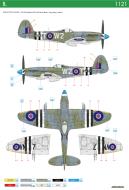

On 5 February 1952, a Spitfire 19 of 81 Squadron based at Kai Tak in Hong Kong reached probably the highest altitude ever achieved by a Spitfire. The pilot, Flight Lieutenant Edward Ted Cyril Powles,[127] was on a routine flight to survey outside-air temperature and report on other meteorological conditions at various altitudes in preparation for a proposed new air service through the area. He climbed to 50,000 ft (15,000 m) indicated altitude, with a true altitude of 51,550 ft (15,710 m). The cabin pressure fell below a safe level and, in trying to reduce altitude, he entered an uncontrollable dive which shook the aircraft violently. He eventually regained control somewhere below 3,000 ft (910 m) and landed safely with no discernible damage to his aircraft. Evaluation of the recorded flight data suggested he achieved a speed of 690 mph (1,110 km/h), (Mach 0.96) in the dive, which would have been the highest speed ever reached by a propeller-driven aircraft if the instruments had been considered more reliable.[124]

That any operational aircraft off the production line, cannons sprouting from its wings and warts and all, could readily be controlled at this speed when the early jet aircraft such as Meteors, Vampires, P-80s, etc, could not, was certainly extraordinary.

Jeffrey Quill[128]

The critical Mach number of the Spitfire's original elliptical wing was higher than the subsequently used laminar-flow-section, straight-tapering-planform wing of the follow-on Supermarine Spiteful, Seafang and Attacker, illustrating that Reginald Mitchell's practical engineering approach to the problems of high-speed flight had paid off.[129]

Variants

Overview

Supermarine Spitfire (early Merlin powered variants); Supermarine Spitfire (late Merlin powered variants); Supermarine Spitfire (Griffon powered variants); and Supermarine Spitfire variants: specifications, performance and armament

Although R. J. Mitchell is justifiably known as the engineer who designed the Spitfire, his premature death in 1937 meant that all development after that date was undertaken by a team led by his chief draughtsman, Joe Smith, who became Supermarine's chief designer on Mitchell's death. As Jeffrey Quill noted: 'If Mitchell was born to design the Spitfire, Joe Smith was born to defend and develop it.'[130]

There were 24 marks of Spitfire and many sub-variants. These covered the Spitfire in development from the Merlin to Griffon engines, the high-speed photo-reconnaissance variants and the different wing configurations. More Spitfire Mk Vs were built than any other type, with 6,487 built, followed by the 5,656 Mk IXs.[37] Different wings, featuring a variety of weapons, were fitted to most marks; the A wing used eight .303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns, the B wing had four .303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns and two 20 mm (.79 in) Hispano cannon, and the C, or universal, wing could mount either four 20 mm (.79 in) cannon or two 20 mm (.79 in) and four .303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns. As the war progressed, the C wing became more common.[131] Another armament variation was the E wing which housed two 20 mm (.79 in) cannon and two .50 in (12.7 mm) Browning machine guns.[132] Although the Spitfire continued to improve in speed and armament because of its limited fuel capacity its range and endurance were limited: it remained 'short-legged' throughout its life except in the dedicated photo-reconnaissance role, when its guns were replaced by extra fuel tanks.[133]

Supermarine developed a two-seat variant known as the T Mk VIII to be used for training, but none were ordered, and only one example was ever constructed (identified as N32/G-AIDN by Supermarine).[134] In the absence of an official two-seater variant, a number of airframes were crudely converted in the field. These included a 4 Squadron SAAF Mk VB in North Africa, where a second seat was fitted instead of the upper fuel tank in front of the cockpit, although it was not a dual-control aircraft, and is thought to have been used as the squadron 'run-about'.[135] The only unofficial two-seat conversions that were fitted with dual-controls were a few Russian lend/lease Mk IX aircraft. These were referred to as Mk IX UTI and differed from the Supermarine proposals by using an inline 'greenhouse' style double canopy rather than the raised 'bubble' type of the T Mk VIII.[135]

In the postwar era, the idea was revived by Supermarine and a number of two-seat Spitfires were built by converting old Mk IX airframes with a second 'raised' cockpit featuring a bubble canopy. Ten of these TR9 variants were then sold to the Indian Air Force along with six to the Irish Air Corps, three to the Royal Netherlands Air Force and one for the Royal Egyptian Air Force.[134] Currently several of the trainers are known to exist, including both the T Mk VIII, a T Mk IX based in the US, and the 'Grace Spitfire' ML407, a veteran flown operationally by 485(NZ) Squadron in 1944.[136][nb 14]

Seafire

The Seafire, a name derived from sea, and Spitfire, was a naval version of the Spitfire specially adapted for operation from aircraft carriers. Although the Spitfire was not designed for the rough-and-tumble of carrier-deck operations, it was considered the best available fighter at the time. The basic Spitfire design did impose some limitations on the use of the aircraft as a carrier-based fighter; poor visibility over the nose, for example, meant that pilots had to be trained to land with their heads out of the cockpit and looking along the port cowling of their Seafire.[137] Like the Spitfire, the Seafire also had a relatively narrow undercarriage track, which meant that it was not ideally suited to deck operations.[138] Early Seafire marks had relatively few modifications to the standard Spitfire airframe; however cumulative front line experience meant that most of the later versions of the Seafire had strengthened airframes, folding wings, arrestor hooks and other modifications, culminating in the purpose-built Seafire F/FR Mk 47.[139]

The Seafire II was able to outperform the A6M5 Zero at low altitudes when the two types were tested against each other during wartime mock combat exercises.[140] However, contemporary Allied carrier fighters such as the F6F Hellcat and F4U Corsair were considerably more robust and so more practical for carrier operations.[141] Performance was greatly increased when later versions of the Seafire were fitted with the Griffon engines. These were too late to see service in World War II.[142]

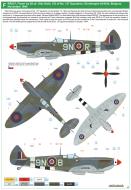

Griffon-engined variants

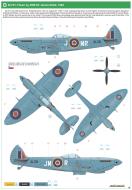

The first Griffon-powered Spitfire, DP845, flown by Jeffrey Quill, 1942 (Mk XII)

The first Rolls-Royce Griffon-engined Mk XII flew in August 1942, and first flew operationally with 41 Squadron in April 1943. This mark could nudge 400 mph (640 km/h) in level flight and climb to an altitude of 33,000 ft (10,000 m) in under nine minutes.[143]

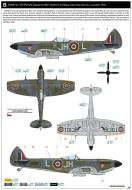

As American fighters took over the long-range escorting of United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) daylight bombing raids, the Griffon-engined Spitfires progressively took up the tactical air superiority role, and played a major role in intercepting V-1 flying bombs, while the Merlin-engined variants (mainly the Mk IX and the Packard-engined Mk XVI) were adapted to the fighter-bomber role.[144] Although the later Griffon-engined marks lost some of the favourable handling characteristics of their Merlin-powered predecessors, they could still outmanoeuvre their main German foes and other, later American and British-designed fighters.[133]

The final version of the Spitfire, the Mk 24, first flew at South Marston on 13 April 1946. On 20 February 1948, almost twelve years from the prototype's first flight, the last production Spitfire, VN496, left the production line. Spitfire Mk 24s were used by only one regular RAF unit, with 80 Squadron replacing their Hawker Tempests with F Mk 24s in 1947.[145] With these planes, 80 Squadron continued its patrol and reconnaissance duties from Wunstorf in Germany as part of the occupation forces, until it relocated to Kai Tak Airport, Hong Kong in July 1949. During the Chinese Civil War, 80 Squadron's main duty was to defend Hong Kong from perceived Communist threats.[146]

Operation Firedog during the Malayan Emergency saw the Spitfire fly over 1,800 operational sorties against the Malaysian Communists.[147] The last operational sortie of an RAF Spitfire was flown on 1 April 1954, by PR Mk 19 Spitfire PS888 flying from RAF Seletar, in Singapore.[148]

The last non-operational flight of a Spitfire in RAF service, which took place on 9 June 1957, was by a PR Mk 19, PS583, from RAF Woodvale of the Temperature and Humidity Flight. This was also the last known flight of a piston-engined fighter in the RAF.[149] The last nation in the Middle East to operate Spitfires was Syria, which kept its F 22s until 1953.[147]

In late 1962, Air Marshal Sir John Nicholls instigated a trial when he flew Spitfire PM631, a PR Mk 19 in the custody of the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight, against an English Electric Lightning F 3 (a supersonic jet-engined interceptor) in mock combat at RAF Binbrook. At the time British Commonwealth forces were involved in possible action against Indonesia over Malaya and Nicholls decided to develop tactics to fight the Indonesian Air Force P-51 Mustang, a fighter that had a similar performance to the PR Mk 19.[150] The first airframe (PM631) developed mechanical issues which removed it from the trial. Another PR Mk 19, PS853, which is now owned by Rolls-Royce, was on gate-guard duties at Binbrook, having been retired from the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight (BBMF) one year before. It had been maintained in running condition by ground crews at Binbrook, and after a short time was participating in the trials. At the end of the trials, RAF pilots found that Firestreak infra-red guided missiles had trouble acquiring the Spitfire due to a low exhaust temperature, and decided that the twin ADEN 30 mm (1 in) cannons were the only weapons suited to the task, which was complicated by the tight turning circle of the Spitfire, and the Lightning's proclivity for over-running the Spitfire. It was concluded that the most effective and safest way for a modern jet-engined fighter to attack a piston-engined fighter was to engage full afterburner at an altitude lower than the Spitfire, and behind it to perform a hit-and-run attack, contrary to all established fighter-on-fighter doctrine at that time.[151][152]

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred