Cactus Air Force - Guadalcanal Campaign

Cactus Air Force refers to the ensemble allied air power assigned to the island of Guadalcanal from August 1942 until December 1942 during the early stages of the Guadalcanal Campaign, particularly those operating from Henderson Field. After December, the official name of the unit became Allied Air Forces in the Solomons, but Cactus Air Force was still used frequently to refer to the organization. The term 'Cactus' comes from the Allied code name for the island. In April, 1943 the organization was redesignated as AirSols.

Background

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked the U.S. Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The attack crippled much of the U.S. battleship fleet and led to a state of war between the two nations. In launching this war, Japanese leaders sought to neutralize the American fleet, seize possessions rich in natural resources, and obtain strategic military bases to defend their far-flung empire. Japanese forces also attacked and took control of the Philippines, Thailand, Malaya, Singapore, the Dutch East Indies, Wake Island, New Britain, and Guam.

Two attempts by the Japanese to extend their defensive perimeter in the south and central Pacific were thwarted in the battles of Coral Sea (May 1942) and Midway (June 1942). These two strategic victories for the Allies provided an opportunity to take the initiative and launch an offensive against the Japanese somewhere in the Pacific. The Allies chose the Solomon Islands, specifically the southern Solomon islands of Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Florida.

Allied strategists knew the Japanese Navy had occupied Tulagi in May 1942 and had constructed a seaplane base near there. Concern grew when in early July 1942 the Japanese Navy began constructing a large airfield near Lunga Point on nearby Guadalcanal. These bases, when complete, would protect Japan's major base at Rabaul, threaten Allied supply and communication lines, and establish a staging area for possible future offensives against Fiji, New Caledonia, and Samoa.

The Allied plan to attack the southern Solomons was conceived by U.S. Admiral Ernest King, Commander in Chief, United States Fleet. He proposed the offensive to deny the use of the southern Solomon islands by the Japanese as bases to threaten the supply routes between the U.S. and Australia, and to use them as starting points for a campaign with the goal of isolating the major Japanese base at Rabaul while also supporting the Allied New Guinea campaign, with the eventual goal of opening the way for the U.S. to retake the Philippines. U.S. Admiral Chester Nimitz, Allied commander in chief for Pacific forces, created the South Pacific theater, with U.S. Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley place in command on June 19, 1942, to direct the Allied offensive in the Solomons.

On August 7, 1942, the 1st Marine Division landed on Guadalcanal and captured the airfield marking the first offensive action taken by the Allies during in the Pacific Theater. Work began on the airfield immediately, mainly using captured Japanese equipment. On August 12, the airfield was renamed Henderson Airfield after Major Lofton Henderson, who died at the Battle of Midway and was the first Marine pilot killed during the battle. By August 18, the airfield was ready for operation.

Henderson Field

When the first planes began arriving, Henderson could barely be described as an airfield. It was an irregularly shaped blob cut out of the island growth, half in and half out of a coconut grove, with a runway that was too short and few revetments to protect the aircraft from shrapnel. Upon landing on Henderson on September 4, the Commanding Officer of Marine Aircraft Group 25, Colonel W. Fiske Marshall described the field by stating it 'looked like a Doré drawing of hell.'

The runway was a northwest to southeast running, 2,400-foot (730 m) long gravel surface with an extra 1,000 feet (300 m) of matting that was frequently pockmarked with craters from Japanese artillery and naval gunfire. The strip was in such poor condition that it caused as many losses to aircraft as enemy action. In the heat, the field was a bowl of black dust which fouled the planes' radial engines and when it rained the field quickly turned muddy, miring planes in liquid muck. Major Marion Carl described it as '...the only place on earth where you could stand up to your knees in mud and still get dust in your eyes.' The heavier SBD dive bombers had it the worst as their hard rubber tires, designed for carrier landings, ripped up the runways like a plowshare. Wooden wheels were experimented with but these did not fare any better. The runway was extended and widened several times during the campaign and was 3,800 feet (1,200 m) long and 150 wide by September 4.

The field was also very close to the thinly held lines of the 1st Marine Division so security was always a concern. There were no fuel trucks, hangars or repair facilities. Damaged aircraft were cannibalized for parts, and with no bomb hoists all aircraft munitions had to be hand loaded onto aircraft. Fuel, always critically low, had to be hand pumped out of 55 gallon drums. Even after the arrival of fuel trucks, gas still had to be hand pumped into the trucks.

On September 9, 1942 the U.S. 6th Naval Construction Battalion (SeaBees) opened a second runway about a mile to the east of Henderson Field's original runway. The new runway was called 'Fighter 1,' consisted of tamped-down sod, and was about 4,600 feet (1,400 m) long and 300 feet (91 m) wide. The Marine fighter squadrons began operating out of Fighter 1 while the rest of the aircraft operating out of Henderson Field continued to use the original runway, which thereafter was referred to as 'Bomber Field No. 1.'

Henderson's facilities began to improve around November 15, when it was officially declared a Marine Corps Air Base. Proper runways began to be installed using imported coral since the local coral was deemed too rotten and slushy.

Living conditions

Living conditions on Guadalcanal were some of the most difficult ever faced by Marine aviation. Pilots and mechanics lived in mud floor tents in a flooded coconut plantation called 'Mosquito Grove.' These living conditions led to most Marines contracting a tropical disease such as malaria, dysentery, dengue fever, beriberi or a fungal infection. At night, Japanese naval ships would bombard the airfield and by day Japanese artillery was a constant problem. The worst night for this was on October 13, 1942 when two Japanese battleships lobbed more than 700 rounds onto Henderson Airfield to provide cover for the Japanese navy's landing of reinforcements further west on the island. Also, everyday around noon, a flight of 20 to 40 Mitsubishi G4M 'Betty bombers' would fly in at 20,000 feet (6,100 m) in a perfect 'V formation' to bomb the airfield. They were always escorted by a flight of A6M Zeros and helped make life on the island even more miserable.

Commanders

From the time of the first Marine squadron landed on August 20 until August 25 there was no commanding officer for Marine air, which instead reported directly to General Vandegrift. The Marines had not designated an air operations commander, the Army already had a squadron present and the field had already acquired the air of a naval base after having been promised to certain naval units. The first Marine commander was Colonel William W. Wallace but he only retained command temporarily. Cactus Air Force technically was under the command of Rear Admiral John S. McCain, who commanded all land based Allied aircraft in the South Pacific. Vandegrift and his operational commanders, however, exercised local command over the Allied aircraft operating out of Henderson Field.

On September 3, 1942, the fortunes of the beleaguered aviators changed with the arrival of Brigadier General Roy Geiger on-board the first SCAT plane to land on the island, an R4D Skytrain. As the 'Commander, Aircraft, Guadalcanal' (ComAirCACTUS) and the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, Geiger set up his headquarters in a wooden Japanese pagoda that was up on a hill about 200 yards (180 m) from the airfield. Through his energy, example and sheer force of personality he raised the collective spirits of the squadrons survivors. He was described as ...curt, cold and some said ruthless....he was determined to squeeze the ultimate ounce of performance from men and machines. During his time in command, it was said that there was a, '...sense of desperation but never defeatism.' Ultimately, the strain of command and harsh living conditions seriously fatigued, both mentally and physically, the then 57 year old Geiger. Geiger turned over the command on November 7 to his Chief of Staff, Brigadier General Louis E. Woods.

Brigadier General Woods, a 21 year aviation veteran, commanded the Cactus fliers during what was viewed as the lowest point of the campaign. He was, however, the right man for the job and quickly transformed from a, 'kindly colonel to a blood thirsty brigadier general.' Woods also turned the Cactus command over, this time the day after Christmas to Brigadier General Francis P. Mulcahy, then Commanding General of the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing.

Japanese

The great majority of the Japanese aircraft engaged by the Cactus Air Force during its history were from Imperial Japanese Navy air units. On August 7, when the Guadalcanal campaign began, the 5th Air Attack Force, under Rear Admiral Sadayoshi Yamada, operated from Rabaul, New Britain and Lae, Papua New Guinea and was responsible for naval air operations in eastern New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. The 5th was a hybrid organization composed mainly of attached units from the 25th Air Flotilla and reported to the 11th Air Fleet (also called the 'Base Air Force'), under Nishizo Tsukahara. On the morning of August 7, the 5th's air strength consisted of 39 fighters, 32 medium bombers, 16 dive bombers, and 17 seaplanes, including the 15 seaplane aircraft at Tulagi that were destroyed in the initial Allied air strikes during the landings on Tulagi and Guadalcanal.

The 5th's principal bomber unit was the 4th Air Group that flew Mitsubishi G4M 'Betty' bombers. Twenty-four of the fighter aircraft in the 5th belonged to the Tainan Air Group under Captain Masahisa Saito. The Tainan contained of some of the top-scoring Japanese fighter aces and flew the A6M2 Zero fighter. With 55 pilots and but 24 aircraft, only the most experienced and able Tainan pilots were allowed to consistently participate in combat operations. The dive bombers (Aichi D3A1 'Vals') and the rest of the fighters (A6M3 Zeros) belonged to the 2nd Air Group. Most of the Vals were lost during the August 7 and 8 strikes on the Allied landing forces. On August 7 and 8, the Misawa Air Group of the 6th Air Attack Force (also called the 26th Air Flotilla) under Vice Admiral Seigo Yamagata from Tinian with 27 Bettys joined the 5th Air Attack Force at Rabaul. Admiral Tsukahara also moved from Tinian to Rabaul to directly supervise air operations against Allied forces around Guadalcanal.

The 4th and Misawa Air Groups took heavy losses during attacks on the Allied landing fleets off Guadalcanal on August 7 and 8, losing 24 bombers and 153 crewmen killed while the Tainan Air Group lost four Zeros and four pilots. Until reinforcements could arrive, the 5th was unable to continue attacking Marine positions on Guadalcanal, giving the U.S. time to prepare the captured airfield at Lunga Point uninterrupted by air attack. On August 20, 19 Bettys from the Kisarazu Air Group of the 6th Air Attack Force arrived at Kavieng. On September 2, ten Bettys from the Chitose Air Group of the 24th Air Flotilla joined them at Kavieng. Both groups participated in subsequent bombing raids on Guadalcanal. Thirteen Zeros and pilots from the 6th Air Group joined the 2nd Air Group at Rabaul on August 31 and began flying combat missions over Guadalcanal on September 11.

From October 1 until the end of the war, the 11th Air Fleet was commanded by Jinichi Kusaka, also located at Rabaul. Some notable pilots flying with the 11th Air Fleet included Hiroyoshi Nishizawa and Junichi Sasai.

A force of Japanese seaplanes called the R-Area Air Force was created on August 28 under Rear Admiral Takatsugu Jojima and operated from Rabaul as well as forward operating bases at Buin, the Shortland Islands, and Rekata Bay, Santa Isabel. The R-Area aircraft came from the four squadrons assigned to the Japanese seaplane tenders Kamikawa Maru, Chitose, Sanyo Maru, and Sanuki Maru. The R-Area Air Force mainly provided cover for Japanese convoys delivering troops and supplies to Guadalcanal, conducted reconnaissance missions around the Solomon Islands' area, and occasionally attacked Henderson Field. Also, air units from Japan's Combined Fleet's aircraft carriers, including Shōkaku, Junyō, Zuikaku, and Ryūjō, either operating from land bases with the 11th Air Fleet, or operating from the carriers themselves, engaged Cactus Air Force aircraft at various times during the Guadalcanal campaign.

Operations

August

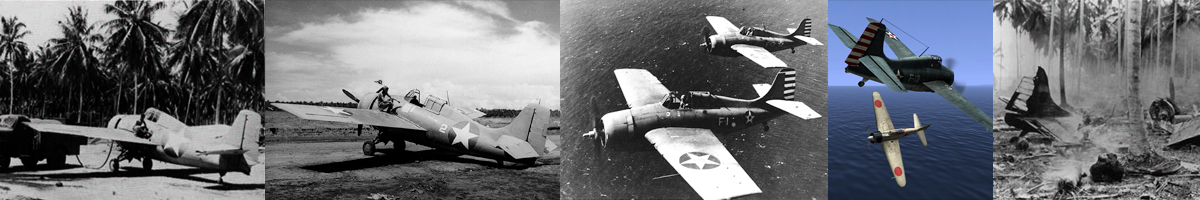

On August 20, Marine pilots from Marine Aircraft Group 23 (MAG-23) with eighteen F4F Wildcats of VMF-223 led by Major John L. Smith and a dozen SBD-3s of VMSB-232 led by Lieutenant Colonel Richard Mangrum, flying from the U.S. escort aircraft carrier Long Island, landed at Henderson, and were conducting combat operations the next day. They were joined on August 22, by the U.S. Army's 67th Pursuit Squadron under Major Dale Brannon with five Army P-400s (an export version of the P-39), and on August 24 by eleven SBDs from the U.S. aircraft carrier Enterprise which were unable to land on their ship because of battle damage sustained during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. At the end of August they were joined by nineteen more Wildcats from VMF-224 under Major Robert E. Galer and twelve more SBDs from VMSB-231, also part of MAG-23. This varied assortment of Army, Marine, and Navy pilots and planes was the beginnings of the Cactus Air Force.

August 21 brought the first Marine air combat but it resulted in mixed results. Japanese Zeros from the Tainan Air Group on a bomber escort mission (the bombers were fruitlessly searching for U.S. carriers south of Guadalcanal) passed over Henderson on their way back to Rabaul and six of them were met by four Cactus F4F Wildcats at 14,000 feet (4,300 m). The engagement resulted in Major Smith claiming the first air to air victory for the CAF but two of the other pilots crashed while landing their damaged aircraft, with both of the Wildcats deemed a total loss except for salvage parts. The Japanese actually suffered no losses in the engagement. That same night an SBD Dauntless blew a tire on takeoff causing it to ground loop and crash for another aircraft loss.

On August 24, during the naval Battle of the Eastern Solomons between aircraft carrier forces of Japan and the U.S. east of the Solomon Islands, Japanese Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo sent the light carrier Ryūjō ahead of the main Japanese warship force to send an aircraft attack force against Henderson Field. The Ryūjō mission was most likely in response to a request from Nishizo Tsukahara, the naval commander at Rabaul, for help from the Japanese combined fleet in neutralizing Henderson Field. At 12:20 and 200 miles (320 km) northeast of Guadalcanal, Ryūjō launched six 'Kate' bombers and 15 A6M Zero fighters to attack Henderson Field in conjunction with an attack by 24 'Betty' bombers and 14 Zero fighters from Rabaul. Unknown to the Ryūjō force, however, the Rabaul aircraft had encountered severe weather and returned to their base at 11:30. The Ryūjō aircraft arrived over Henderson Field at 14:23 and tangled with 14 Marine Wildcats and four Army P-400s while bombing the airfield. In the resulting engagement three Kates, three Zeros, and three Marine fighters were shot down and no damage was done to Henderson Field. Two Marine pilots were killed in the engagement as well as eight Japanese aircrew. All of the Japanese aircraft were eventually lost as, while they were attacking Henderson Field, Ryūjō was sunk by aircraft from the U.S. aircraft carrier Saratoga, forcing the Japanese aircraft to ditch in the ocean upon returning to the previous location of their carrier.

VMF-223 (Marine Fighting Squadron 223) Nickname: "Bulldogs"

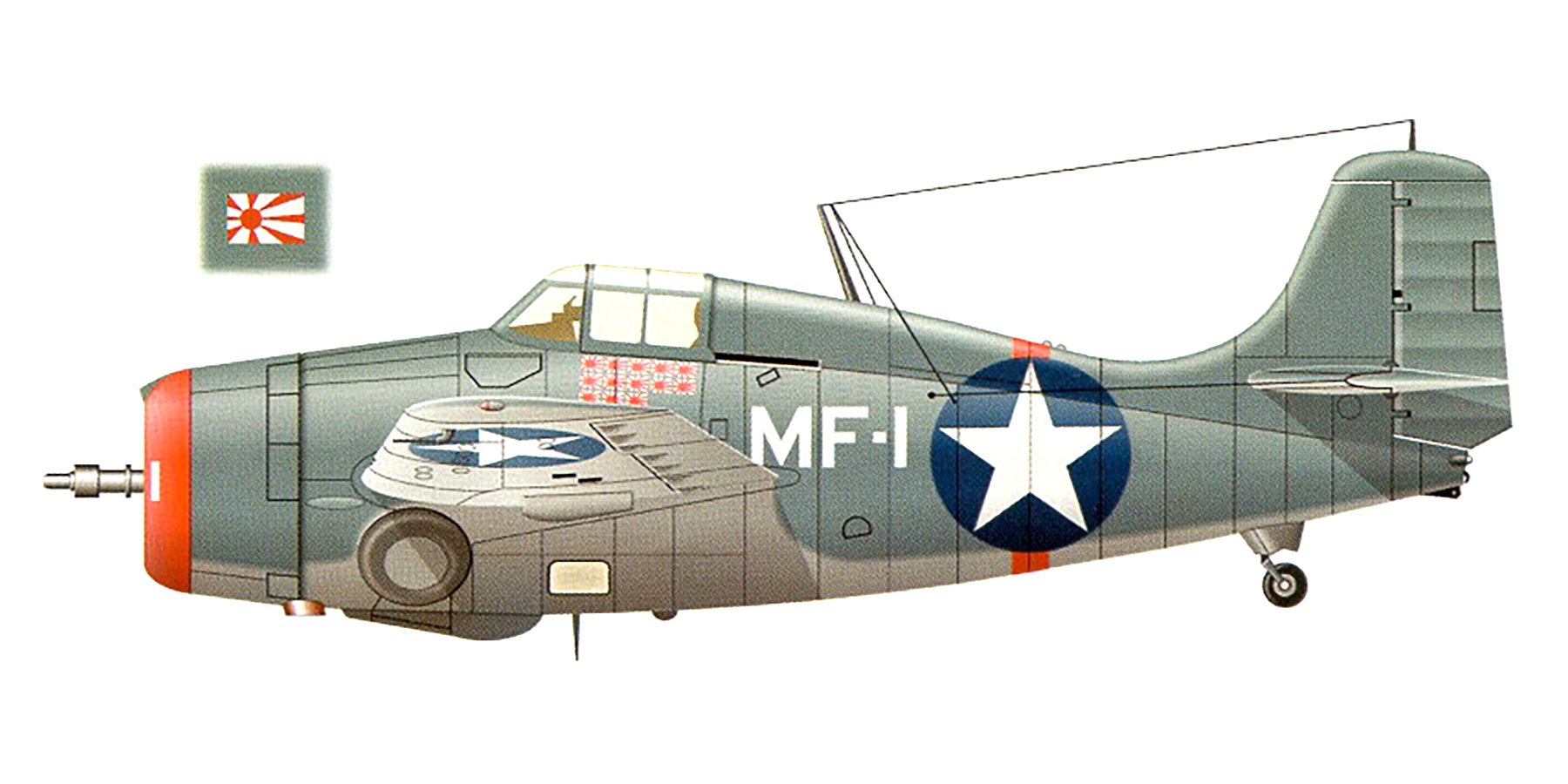

Commanding Officer: Major John L. Smith

Details: VMF-223 was one of the first Marine fighter squadrons to arrive at Henderson Field, landing on August 20, 1942, as part of the "Cactus Air Force" (named after the Allied code name for Guadalcanal, "Cactus"). Equipped with F4F-4 Wildcats, they flew from the hastily constructed airstrip under grueling conditions, engaging Japanese aircraft in intense aerial combat. Major Smith became an ace during the campaign, credited with 19 kills, and the squadron played a pivotal role in defending against Japanese air raids.

24th August 1942 – VMF-223’s First Major Clash

Units Involved: VMF-223

Context: Just four days after arriving at Henderson Field on August 20, VMF-223 faced its first significant test. The squadron had been scrambled repeatedly since arrival, but this engagement marked a large-scale Japanese air raid aimed at neutralizing the airfield.

Time: Midday

Enemy Force: Approximately 15-20 Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bombers escorted by A6M Zero fighters from Rabaul.

Marine Response: Major John L. Smith led a dozen F4F-4 Wildcats to intercept the raid. Taking off under artillery fire from Japanese ships offshore, the Wildcats climbed to meet the incoming formation.

Combat: The Wildcats engaged the bombers first, downing several before the Zeros could effectively intervene. Smith and his pilots used hit-and-run tactics, exploiting the Wildcat’s durability to survive Zero attacks. The Marines claimed 16 enemy aircraft (10 bombers and 6 fighters), though postwar records adjusted this to around 11-13 confirmed kills.

Losses: VMF-223 lost two Wildcats, with one pilot killed and another wounded.

Significance: This engagement demonstrated the Wildcat’s effectiveness in disrupting Japanese bombing runs and boosted morale among the defenders of Henderson Field. Smith himself scored his first kills of the campaign here, beginning his rise to ace status.

VMF-224 (Marine Fighting Squadron 224) Nickname: "Bengals"

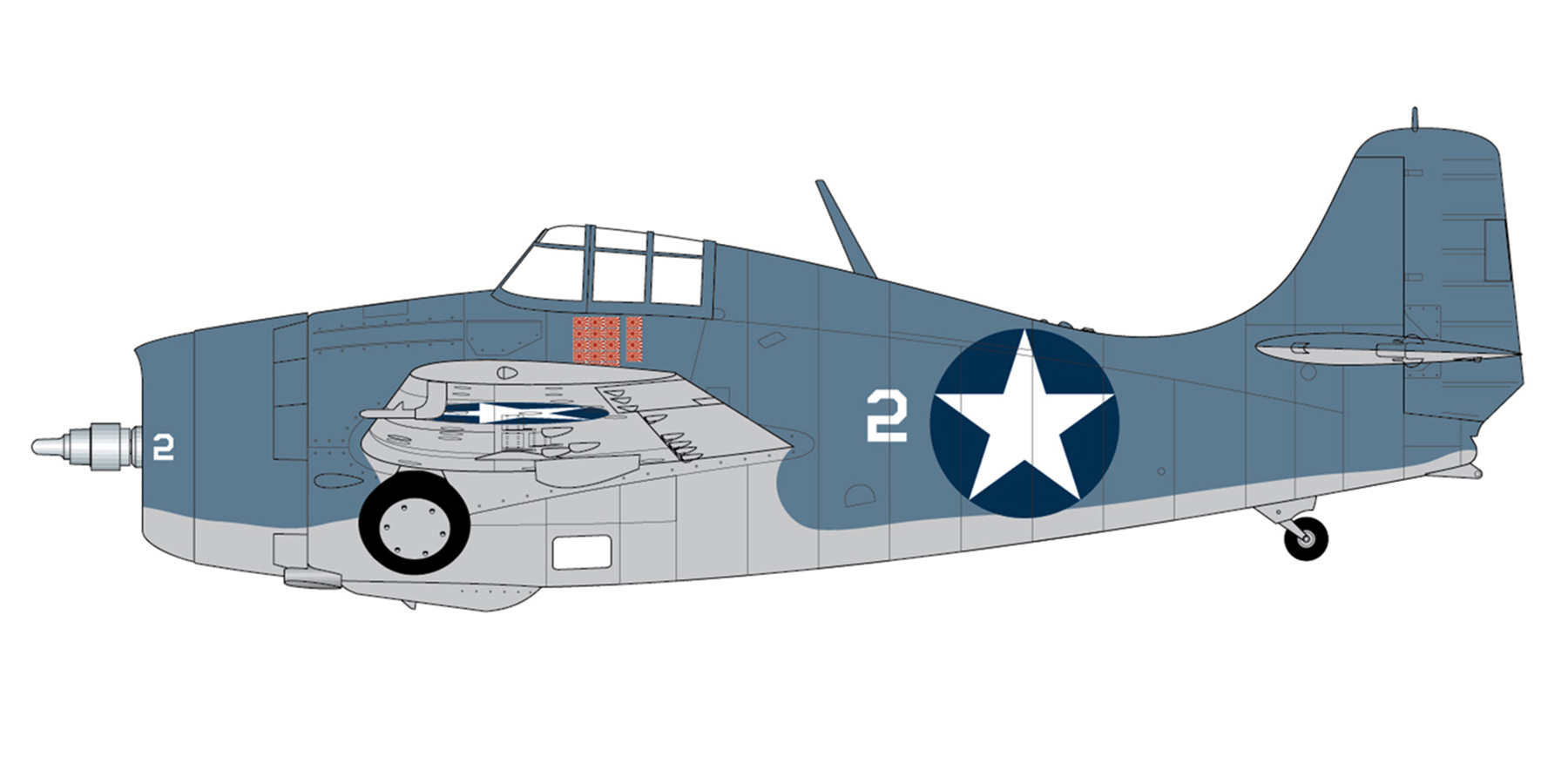

Commanding Officer: Major Robert E. Galer

Details: VMF-224 arrived at Guadalcanal on August 30, 1942, reinforcing VMF-223. Also equipped with F4F Wildcats, the squadron bolstered the Cactus Air Force’s fighter strength. Major Galer, a skilled pilot and tactician, earned the Medal of Honor for his leadership and combat performance, downing 13 enemy aircraft. VMF-224 faced constant Japanese bombing and strafing attacks while operating from Henderson Field.

VMF-212 (Marine Fighting Squadron 212) Nickname: "Hell Hounds"

Commanding Officer: Major Harold W. Bauer

Details: VMF-212 arrived later in the campaign, with elements reaching Guadalcanal in October 1942. Led by Major Bauer, who also earned the Medal of Honor for his actions (including 11 aerial victories), the squadron flew Wildcats in combat against Japanese forces. Bauer was lost in action on November 14, 1942, after being shot down but made significant contributions to the air defense effort prior to that.

These squadrons operated under the umbrella of MAG-23 (Marine Aircraft Group 23), which coordinated Marine air units during the campaign. The Wildcats they flew were primarily the F4F-4 variant, featuring folding wings and six .50-caliber machine guns, though they were often outmatched in speed and maneuverability by the Japanese A6M Zero. Despite this, the Wildcat’s durability and the skill of Marine pilots allowed them to achieve a favorable kill ratio through tactics like the "Thach Weave."

The Cactus Air Force, a mix of Marine, Navy, and Army Air Forces units, was instrumental in turning the tide at Guadalcanal. VMF-223 and VMF-224 were the backbone of early fighter operations, while VMF-212 reinforced them as the campaign progressed. By the end of 1942, the Wildcat was gradually being replaced by the more advanced F4U Corsair, but it remained the primary Marine fighter during the critical early months of the campaign.

On August 31, the U.S. aircraft carrier Saratoga was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine. Forced to return to Pearl Harbor for repairs, most of Saratoga's aircraft and aircrew remained behind at Espiritu Santo. Admiral McCain planned to send some of these aircraft to reinforce the CAF at Guadalcanal.

September

On September 2, the U.S. Marine 3rd Defense Battalion began operating an air search radar at Henderson Field, which, along with reports from the coastwatchers helped provide early warning of incoming Japanese aircraft.

September 13, 1942 – VMF-224 and the “Day of the Aces”

Units Involved: VMF-224, with support from VMF-223

Context: By mid-September, Japanese air attacks intensified as they sought to support ground offensives against the Marine perimeter. This day saw one of the heaviest raids of the campaign.

Details - Time: Late morning

Enemy Force: Over 30 aircraft, including G4M bombers and a strong Zero escort, launched from Rabaul.

Marine Response: Major Robert E. Galer of VMF-224 led a mixed force of Wildcats from both VMF-224 and VMF-223, totaling about 16-18 fighters. They scrambled amidst dust and chaos as Japanese artillery shelled the field.

Combat: The Wildcats climbed to 20,000 feet to intercept the bombers before they could release their payloads. Galer personally shot down two Zeros and a bomber, while other pilots, including Captain Marion Carl of VMF-223 (already an ace), added to the tally. The Marines claimed 17 kills (9 bombers, 8 fighters), with postwar analysis confirming around 12-14. The Thach Weave tactic—where pairs of Wildcats crisscrossed to protect each other—was used effectively against the agile Zeros.

Losses: Three Wildcats were shot down, with two pilots surviving to be rescued.

Significance: This was a peak day for the Cactus Air Force, with multiple pilots achieving ace status. Galer’s leadership under fire later contributed to his Medal of Honor citation.

By September 3, the day of Geiger's arrival, the CAF consisted of only 64 flyable aircraft. Due to the heavy losses that the CAF had sustained, Admiral McCain decided to immediately deploy Saratoga's fighter squadron to Guadalcanal. On September 4, 24 F4Fs of VF-5 flew from Espiritu Santo to Henderson Field.

From September 1 through September 8 the Japanese air units at Rabaul concentrated on providing air cover for Imperial Japanese Army forces operating along the Kokoda Track in New Guinea. On September 9, however, the Japanese resumed air operations against Henderson Field with the objective of destroying the CAF and isolating the U.S. forces on Guadalcanal.

Between August 21 and September 11, the Japanese raided Guadalcanal a total of ten times, losing 31 aircraft destroyed and seven more heavily damaged, primarily due to the defensive efforts of CAF aircraft. Most of the Japanese aircrews in the destroyed aircraft were killed. During this same time, the CAF Marine fighter squadrons lost 27 aircraft with nine pilots killed.

On September 12, 25 Bettys and 15 Zeros from Rabaul raided Henderson Field. Alerted by coastwatcher Donald Kennedy and by radar at Henderson Field, 20 Wildcat fighters from the Marine and Navy fighter squadrons took off to intercept the raid. In the resulting battle, two Bettys were downed by Marine anti-aircraft fire and four Bettys and one Zero were shot down by the Wildcats. One U.S. Navy pilot died attempting to land his damaged fighter back at Henderson following the action.

That night the field was shelled by the Japanese cruiser Sendai and three destroyers that were supporting the Japanese Army attacks on the Lunga perimeter in the first night of the Battle of Edson's Ridge. The shelling killed two pilots from VMSB-232 and one pilot from VMSB-231, but didn't damage any aircraft or the airfield.

On September 13, 18 wildcats arrived at Henderson from the carriers Hornet and Wasp. The morning of this same day, Tsukahara sent a reconnaissance mission consisting of two Type 2 aircraft escorted by nine Zeros to find out if the Japanese Army had succeeded in capturing Henderson Field during the night. The Zeros tangled with Cactus fighters from VMF-223, 224, and VF-5, losing four Zeros along with their pilots. Cactus lost four fighters, two in combat and two to accidents with two Cactus pilots killed. An afternoon raid the same day by 27 Bettys and 12 Zeros attacked Henderson at 14:00 and again resulted in intense clashes with the Cactus defenders. In the skirmish, two Bettys were lost and two were heavily damaged, with three crewmen killed and six captured. Two Wildcats, one each from VMF-212 and VF-5 were lost, with both pilots killed. That same day two R Area float Zeros from Rekata Bay swept over Lunga Point and shot down a scout SBD from VMSB-231, killing both of its crewmen. Another CAF scout SBD from VS-3 ditched in the ocean that afternoon during their search patrol and neither of the two crewmen were ever seen again. Later that day 12 VS-3 SBD's and six VT-8 TBF's arrived at Henderson as reinforcements.

13th September 1942

Time: Late morning

Location: Above Henderson Field, Guadalcanal

Marine Units: VMF-224 (Major Robert E. Galer) and VMF-223 (Major John L. Smith), totaling 16-18 F4F-4 Wildcats

Japanese Force: Approximately 30-35 aircraft—18 Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bombers escorted by 15-20 A6M2 Zero fighters from the 2nd Air Group and Tainan Air Group, based at Rabaul

Outcome: Marines claimed 17 kills (9 bombers, 8 fighters), with postwar records confirming 12-14. Three Wildcats lost, two pilots survived.

Marine Perspective and Details

Preparation and Scramble: The Cactus Air Force detected the incoming raid via coastwatcher reports and rudimentary radar. Henderson Field was already under artillery fire from Japanese ground forces, and the runway was a mess of mud and craters. Major Galer and Major Smith led their Wildcats into the air amidst dust clouds, climbing to 20,000 feet to gain an altitude advantage. Fuel and ammo were critically low—some planes had only half loads.

Combat: The Wildcats prioritized the G4M bombers, diving through the Zero escort to disrupt the formation. Galer shot down a bomber and two Zeros, maneuvering aggressively despite taking hits. Captain Marion Carl (VMF-223) used the Thach Weave with his wingman to bag a Zero and a bomber, dodging the Zeros’ superior agility. The fight lasted about 20 minutes, with Wildcats scattering the bombers, many of which jettisoned their bombs over the jungle rather than the airfield.

Pilot Experience: Marine pilots were exhausted but battle-hardened. Carl later recalled, “You didn’t think about the odds—just the next target. The Wildcat could take a beating, and that saved us.” Galer’s Medal of Honor citation praised his “conspicuous heroism” in leading under fire. The psychological boost of downing enemy planes outweighed the physical toll of malaria and sleepless nights.

Japanese Tactics

Mission Objective: The Japanese aimed to neutralize Henderson Field to support their ground offensive, specifically the Edson’s Ridge (Bloody Ridge) attack that began the previous night. The G4M bombers carried 500-kg bombs to crater the runway and destroy parked aircraft, while the Zeros ensured their safe delivery.

Formation and Approach: The bombers flew in a tight V-formation at 20,000-22,000 feet, maximizing defensive firepower from their 20mm tail guns and 7.7mm machine guns. The Zeros flew a loose “finger-four” formation above and to the sides, ready to peel off and engage interceptors. The raid approached from the northwest, using cloud cover to mask their advance until the last 30 miles.

Engagement Strategy: Japanese doctrine emphasized protecting the bombers at all costs. Zeros were tasked with diving on Wildcats as they attacked, relying on their superior speed (330 mph vs. Wildcat’s 290 mph) and climb rate (3,000 ft/min vs. 2,000 ft/min) to outmaneuver them. Once engaged, Zeros aimed for quick kills with their 20mm cannons, though their light construction made them vulnerable to the Wildcat’s .50-caliber rounds.

Adaptation: By September, Japanese commanders had noted the Wildcats’ resilience and teamwork. They instructed Zero pilots to avoid prolonged dogfights and focus on boom-and-zoom attacks—diving, firing, and climbing away. However, the bombers’ slow speed (265 mph max) and lack of armor left them exposed if the Zeros were drawn off.

Japanese Pilots’ Points of View

Lieutenant Saburo Sakai (Tainan Air Group, Zero Pilot): Sakai, one of Japan’s top aces (64 claimed kills by war’s end), flew in earlier Guadalcanal raids and likely influenced tactics for this mission, though he was recovering from wounds by September 13. In his memoir Samurai!, he described the frustration of facing Wildcats: “The American planes were slow, but they wouldn’t go down easily. You’d hit them, see smoke, and still they’d fight. Our Zeros were like glass—one burst and you were done.” On this day, his squadron mates likely echoed his experience, finding the Wildcats’ durability maddening.

Petty Officer Tadayoshi Koga (Zero Pilot, Posthumous Insight): Koga, killed earlier in 1942 (his intact Zero was recovered by the U.S.), represented the typical Zero pilot’s mindset—confidence in their aircraft’s agility but awareness of its fragility. Pilots on September 13 would have felt this tension, aiming to out-turn Wildcats in tight circles but risking catastrophic damage from even a short burst of .50-caliber fire.

Unnamed G4M Crewman: Bomber crews dreaded Guadalcanal runs. A surviving G4M gunner from a similar raid told postwar interviewers, “The Wildcats came out of nowhere, diving like hawks. Our guns couldn’t track them fast enough, and the Zeros couldn’t always keep up. You’d see planes ahead explode, and you just prayed.” On September 13, the tight formation broke apart under Wildcat attacks, forcing many crews to dump bombs and flee, lowering morale.

Commander’s View (Likely Lt. Cmdr. Tadashi Nakajima, 2nd Air Group): From Rabaul, planners like Nakajima saw mounting losses as a sign of American tenacity. Postwar records show they underestimated the Cactus Air Force’s ability to sustain operations under bombardment. After September 13, Nakajima reportedly pushed for night raids to avoid daytime fighter opposition, reflecting a tactical shift driven by engagements like this.

Comparative Analysis

Tactical Clash: The Japanese relied on speed and coordination, but the Wildcats’ ruggedness and Marine teamwork (e.g., Thach Weave) countered this. Zeros often chased individual Wildcats, leaving bombers exposed, while Marines ignored losses to focus on the bombers—a trade-off that favored the defenders.

Psychological Impact: Marine pilots felt a grim satisfaction in disrupting the raid, reinforcing their “hold the line” mentality. Japanese pilots, especially Zero aces, grew wary of the Wildcat’s staying power, while bomber crews began calling Guadalcanal “the graveyard of the air groups.”

Material Strain: The Wildcats were battered but repairable; Japan lost irreplaceable pilots and planes. Postwar data shows the Tainan Air Group’s elite cadre was decimated by late 1942, partly due to days like this.

Aftermath

The September 13 engagement weakened Japan’s air strength at a critical moment, allowing Henderson Field to survive the Bloody Ridge assault. Galer and Carl became legends, while Japanese losses (12-14 aircraft) outpaced replacements. From the Japanese side, it underscored the need for a new approach—night bombings and naval bombardments intensified soon after.

On September 14, the R Area force attacked Henderson throughout the day with a total of 24 float fighters and bombers, losing eight of them with no losses to the CAF. A fighter sweep by seven 2nd Air Group Zeros from Rabaul also attacked Lunga that day, losing one aircraft and pilot. A Japanese reconnaissance aircraft was also shot down over Guadalcanal that day. The only CAF loss was one VMF-223 Wildcat that wrecked on takeoff, seriously injuring the pilot.

A lull occurred in the air war over Guadalcanal, with no Japanese air raids occurring between September 14 and September 27 due to bad weather, during which both sides reinforced their respective air units. The Japanese delivered 85 fighters and bombers to their air units at Rabaul while the U.S. brought 23 fighters and attack aircraft to Henderson Field. On September 20, the Japanese counted 117 total aircraft at Rabaul while the CAF tallied 71 aircraft at Henderson Field.

27th September 1942 – The Battle of the Five Aces

Units Involved: VMF-223 and VMF-224

Context: A critical moment in the campaign when Japanese air raids peaked in frequency, testing the endurance of the Cactus Air Force.

Details - Time: Early afternoon

Enemy Force: 18 G4M bombers escorted by 20+ Zeros.

Marine Response: A combined force of 14 Wildcats from VMF-223 (led by Smith) and VMF-224 (led by Galer) intercepted the raid at high altitude.

Combat: The Wildcats tore into the bombers, scattering them before the Zeros could fully engage. Five Marine pilots—Smith, Carl, and three others—each scored multiple kills, with claims totaling 19 enemy aircraft (adjusted postwar to 13-15 confirmed). Smith downed two Zeros, while Carl bagged a bomber and a fighter. The engagement was chaotic, with Wildcats often fighting outnumbered but using teamwork to survive.

Losses: Two Wildcats shot down, one pilot killed.

Significance: This fight highlighted the growing skill of Marine pilots and their ability to inflict disproportionate losses, even as Henderson Field’s defenses were stretched thin.

October

11th October 1942 – VMF-212’s Baptism of Fire

Units Involved: VMF-212

Context: VMF-212 arrived at Guadalcanal in early October to reinforce the depleted Cactus Air Force, just as Japanese naval and air forces launched a major push to retake the island.

Details - Time: Afternoon

Enemy Force: A mixed force of 12 G4M bombers and 15-20 Zeros, part of a coordinated attack with Japanese battleships bombarding Henderson Field that night (the infamous “Night of the Battleships”).

Marine Response: Major Harold W. Bauer, commanding VMF-212, led eight Wildcats into the fray. Despite limited fuel and battle-worn aircraft, they took off to meet the enemy head-on.

Combat: Bauer, flying alone after his wingmen were forced to disengage, attacked the formation single-handedly. He shot down four Zeros in rapid succession, breaking up the bomber formation and forcing many to jettison their bombs early. Other VMF-212 pilots claimed additional kills, totaling 7-9 enemy aircraft downed (postwar records suggest 6 confirmed). Bauer’s aggressive tactics showcased the Wildcat’s resilience as he absorbed hits but kept fighting.

Losses: One Wildcat lost, though Bauer survived this encounter (he would be killed a month later on November 14).

Significance: Bauer’s actions disrupted the Japanese attack, earning him posthumous recognition as a Medal of Honor recipient. This engagement underscored VMF-212’s immediate impact despite its late arrival.

Guadalcanal Flying Ace - Captain Joe Foss, U.S. Marine Corps

In October 1942, VMF-121 pilots and aircraft were sent to Guadalcanal as part of Operation Watchtower to relieve VMF-223, which had been fighting for control of the air over the island since mid-August. On October 9, Foss and his group were catapult launched off the USS Copahee escort carrier and flew 350 miles (560 km) north to reach Guadalcanal. The air group, code named 'Cactus', based at Henderson Field became known as the Cactus Air Force, and their presence played a pivotal role in the Battle of Guadalcanal.] Foss soon gained a reputation for aggressive close-in fighter tactics and uncanny gunnery skills. Foss shot down a Japanese Zero on his first combat mission on October 13, but his own F4F Wildcat was shot up as well, and with a dead engine and three more Zeros on his tail, he landed at full speed, with no flaps and minimal control on Henderson Field, barely missing a grove of palm trees. On 7 November his Wildcat was again hit, and he survived a ditching in the sea off the island of Malaita.

As lead pilot in his flight of eight Wildcats, the group soon became known as 'Foss's Flying Circus', with two sections Foss nicknamed 'Farm Boys' and 'City Slickers.' In December 1942, Foss contracted malaria. He was sent to Sydney, Australia for rehabilitation, where he met Australian ace Clive 'Killer' Caldwell and delivered some lectures on operational flying to RAF pilots, newly assigned to the theater. On January 1, 1943, Foss returned to Guadalcanal, to continue combat operations which lasted until February 9, 1943, although the Japanese attacks had waned from the height of the November 1942 crisis. In three months of sustained combat, Foss's Flying Circus had shot down 72 Japanese aircraft, including 26 credited to him. Upon matching the record of 26 kills held by America's top World War I ace, Eddie Rickenbacker, Foss was accorded the honor of becoming America's first 'ace-of-aces' in World War II. One of the Japanese he shot down was ace Kaname Harada, who became a peace activist and met Foss many years later.

Foss returned to the United States in March 1943. On May 18, 1943, Foss received the Medal of Honor from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The White House ceremony was featured in Life magazine, with the reluctant Captain Foss appearing on the magazine's cover. He then was asked to participate in a war bond tour that stretched into 1944.

Return to combat

In February 1944, Foss returned to the Pacific theater to lead VMF-115, flying the F4U Corsair. VMF-115 was based in the combat zone around Emirau, St. Mathias Group in 1944. It was during this second tour that Foss met and became friends with fellow Marine fighter ace Marion Carl. He also had an opportunity to meet and fly with his boyhood idol, Charles Lindbergh, who was on assignment touring the South Pacific as an aviation consultant. After eight months of operational flying but no opportunities to increase his wartime score, Foss finished his combat service as one of America's top scoring pilots.

Foss again contracted malaria, and was sent home to the Klamath Falls, Oregon Rehabilitation Center. In February 1945, he became operations and training officer at the Marine Corps Air Station Santa Barbara, California.

November

The CAF reached its peak of combat power on November 12 when they were able to count 47 fighters, 23 tactical bombers and 12 medium bombers. After a month and a half of enduring continuous shelling at night the pilots at Henderson got their first crack at a Japanese battleship when the Hiei lost control of her steering gear following the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. The ship was repeatedly attacked by aircraft from Henderson and the USS Enterprise (CV-6). After numerous direct hits she was scuttled by her crew. The first allied units to arrive at Henderson came on November 26 in the form of a squadron of Lockheed Hudsons from the Royal New Zealand Air Force.

December

On December 26 there were 161 aircraft of all types at Guadalcanal.

Tactics employed

Navy and Marine fighter pilots, who had little high flying experience to begin with, were at a disadvantage from the start because their F4F Wildcat was not in the same class as the Japanese A6M Zero when it came to altitude, rate of climb and maneuverability. The Zero was lighter, faster, a better climber and had a cannon as well as machine guns. The pilots learned quickly not to dogfight the Zero. Instead, if they became engaged with one, they would give a quick burst of fire and then dive for home. Cactus pilots had to constantly refine their tactics and techniques, rely on teamwork in dogfights and improve their gunnery to remain effective against the Zeroes.

Because of the Zeroes' maneuverability, U.S. pilots quickly adapted hit and run tactics similar to those of the Flying Tigers in China and the tactic of a two-plane mutually protecting flight section. This technique had previously been developed by John Thach and Edward O'Hare and was known as the 'Thach Weave.' The aircraft would remain in the same general area of one another and if Zeroes showed up they had a better chance of engaging the aircraft on the tails of their wingmen.

One American pilot had remarked,

'One Zero against one Grumman is not an even fight, but with mutual support two Grummans are worth four or five Zeros.'

Disadvantages aside, the Wildcat was not without its merits. The plane was found to be very sturdy compared to the lightly armored Zero, had a self-sealing fuel tank and possessed more than adequate firepower. Marine pilots, very skeptical since Midway, did place a great deal of confidence in their aircraft.

Because they could not effectively dogfight the Zeroes, the Henderson defenders realized that the best they could do was break up each day's raid and live to fight another day. With this in mind their primary targets became the bombers instead of the fighters and many of the tactics introduced were largely devised by Major John L. Smith. American aircraft always sought to initiate the attack at least 5,000 feet (1,500 m) above the Japanese formations and concentrated their attack on the trail aircraft in the formation. This gave them a good angle to shoot at the exposed fuel tanks of the Bettys and also presented a difficult gunnery problem for the bombers as the high overhead passes of the American fighters put them in a blindspot for the Japanese gunners. This tactic also caused the escorting Zeroes to climb and burn precious fuel thus reducing their time over the island.

From September 3 - November 4, 1942 the Cactus Air Force claimed downing 268 Japanese planes in aerial combat and inflicted damage on a number estimated to be as great.

Coastwatchers

Because of the limited number of aircraft and fuel available during the early stages of the campaign the CAF was unable to maintain a standing combat air patrol over Henderson Field. Therefore, it was crucial for the CAF to receive early warnings of incoming Japanese aircraft so that it's aircraft weren't caught on the ground during Japanese air attacks. Members of the Australian Coastwatchers, including W. J. Read in northern and Paul Mason in southern Bouganville, Donald Kennedy on New Georgia, and Geoffrey Kuper on Santa Isabel were able to relay ahead when Japanese airplane formations were heading for the island giving the defenders on Guadalcanal time to get airborne. On August 16, Lieutenant Commander Hugh A. Mackenzie of the Royal Australian Navy, the Deputy Staff Intelligence Officer for the British Solomon Islands Protectorate, set up a radio station at Henderson Field to monitor coastwatcher transmissions and relay their warnings to the CAF. Admiral Bull Halsey would later say the coastwatchers, 'saved Guadalcanal'.

Several coastwatchers were stationed at various points around Guadalcanal, including Martin Clemens (who was also a local official for the British Solomon Islands Protectorate), Leif Schroeder, Donald Macfarlan, Ken Hay, and Ashton Rhoades. These coastwatchers, with help from native Solomon Islanders, helped rescue and return several Allied pilots during the campaign.

Aftermath

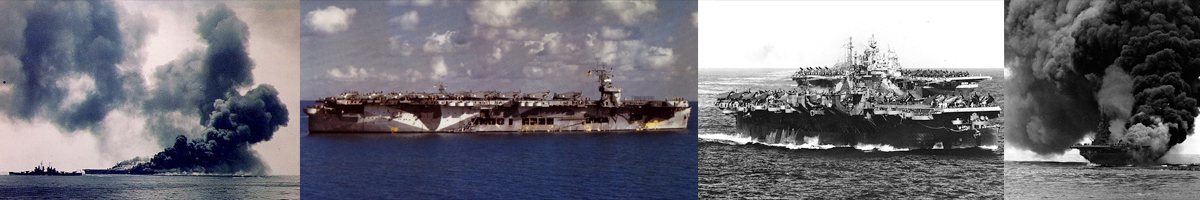

The CAF's dive bombers and torpedo planes sank or destroyed 17 large enemy vessels, including one heavy cruiser (Kinugasa), one light cruiser (Yura), three destroyers (Asagiri, Murakumo, and Natsugumo), and twelve transports, possibly sank three destroyers and one heavy cruiser, and heavily damaged 18 other ships, including one heavy cruiser and five light cruisers. Most notable was the battleship Hiei, which the CAF, along with aircraft from the Enterprise and B-17s from Espiritu Santo, mortally damaged after she took a serious mauling from US warships during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal.

The fifteen Marine combat squadrons that fought on Guadalcanal during this time suffered 94 pilots killed or missing-in-action with another 177 evacuated for wounds or sickness, Total figures for Japanese aerial losses during the campaign were never calculated.

The Battle of Guadalcanal would become the defining point for Marine aviation in World War II and for the next fifty years. The great takeaways for the Marine Corps were the debilitating effects of not having air superiority, the vulnerability of targets such as transport shipping and the vital importance of quickly acquiring expeditionary airfields during amphibious operations.Medal of Honor recipients

Six aviators who served in the 'Cactus Air Force' received the Medal of Honor for their actions during the Battle of Guadalcanal (August 1942-February 1943):

John L. Smith; Robert E. Galer; Joe Foss; Harold W. Bauer; Jefferson J. DeBlanc; James E. Swett

Order of Battle

All aviation units on Guadalcanal were subordinate to Commander, Aircraft, Guadalcanal (ComAirGuadal).

USMC: VMF-112; VMF-121; VMF-122; VMF-123; VMF-124; VMF-212; VMF-223; VMF-224; VMO-251; VMSB-131; VMSB-132; VMSB-141; VMSB-142; VMSB-144; VMSB-231; VMSB-232; VMSB-233; VMSB-234; VMJ-152; VMJ-253

USAAF: 67th Pursuit Squadron; 11th Bomb Group

USN: VS-3; VF-5; VS-5; VS-71; VT-8

USS Enterprise: VF-10; VB-6; VB-10; VS-10; VT-10

Aircraft Flown: F4F Wildcat; SBD Dauntless; TBF Avenger; J2F-5 Duck; P-39 Airacobra; PBY Catalina;

Tactical Evolution of the Wildcats during the Guadalcanal Campaign: The Wildcat’s inferiority to the Zero in speed and climb rate forced pilots to rely on teamwork (e.g., Thach Weave) and the aircraft’s ruggedness. Engagements often occurred at 15,000-25,000 feet, where Wildcats could dive on bombers before tangling with escorts.

Conditions: Pilots faced constant fatigue, malaria, and shortages of fuel and parts. Henderson Field was a muddy, cratered mess, making takeoffs and landings hazardous.

Impact: These engagements collectively ensured Henderson Field remained operational, allowing Allied forces to maintain air cover and eventually secure Guadalcanal by February 1943.

Detailed Analysis of Marine Flying Units Operating Grumman Wildcats During the Guadalcanal Campaign in 1942

The Guadalcanal campaign, fought between August 1942 and February 1943, was a pivotal engagement in the Pacific Theater of World War II, marking the first major Allied offensive against Japanese forces in the Solomon Islands. This report provides a comprehensive examination of the U.S. Marine Corps flying units that operated the Grumman F4F Wildcat during the campaign, focusing on the year 1942, and includes detailed historical context, unit activities, and operational impacts.

Marine Flying Units and Their Operations

The Grumman F4F Wildcat, a rugged single-engine fighter aircraft, was the primary Marine Corps fighter during the early stages of the Pacific War. It was equipped with folding wings and six .50-caliber machine guns, making it suitable for carrier and land-based operations. The Marine flying units, designated as Marine Fighting Squadrons (VMF), were integral to the Cactus Air Force, the collective term for Allied air units based at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. The following units were identified as operating Wildcats during the campaign in 1942:

VMF-223 (Bulldogs): Activated prior to the war, VMF-223 was one of the first Marine fighter squadrons to arrive at Henderson Field, landing on August 20, 1942, as part of the initial contingent aboard the escort carrier USS Long Island (CVE-1) (Time of the Aces: Marine Pilots in the Solomons). Led by Major John L. Smith, they flew F4F-4 Wildcats and engaged Japanese raiders from the outset, intercepting enemy formations and claiming significant kills, including 11 enemy aircraft on October 3, 1942. Their operations were critical in the early defense of the airfield, facing constant Japanese air raids and naval bombardments.

VMF-224 (Bengals): Arriving on August 30, 1942, VMF-224 reinforced VMF-223, also equipped with F4F-4 Wildcats (Time of the Aces: Marine Pilots in the Solomons). Under Major Robert E. Galer, the squadron played a pivotal role in intercepting Japanese bombers, with Galer himself becoming an ace and later earning the Medal of Honor for his leadership. On October 3, 1942, they accounted for 11 enemy aircraft alongside VMF-223, showcasing their effectiveness in combined operations.

VMF-212 (Hell Hounds): Formed on March 1, 1942, at MCAS Ewa, Hawaii, VMF-212 initially operated from New Caledonia and Efate before sending detachments to Henderson Field in October 1942, with the entire squadron committed by mid-October (VMFA-212 | Military Wiki). Led by Major Harold W. Bauer, they flew F4F Wildcats and engaged in combat, with Bauer becoming an ace and earning the Medal of Honor posthumously after being lost in action on November 14, 1942. Their arrival bolstered the Cactus Air Force during a critical phase of the campaign.

VMF-111 (Devil Cats): Activated on September 1, 1942, at Marine Corps Air Station Santa Barbara, California, VMF-111 was equipped with F4F Wildcats and deployed to Henderson Field, arriving on November 15, 1942 (VMF-111 - Wikipedia). Upon arrival, they immediately began flying combat missions in support of Allied ground forces and conducting patrols to intercept Japanese air raids, operating Wildcats until mid-1943 when they transitioned to F4U Corsairs. Their presence in November and December 1942 added to the defense efforts during the latter part of the year.

These units operated under the umbrella of Marine Aircraft Group 23 (MAG-23), which was tasked with supporting ground operations and air defense of the island. The Wildcats were often outmatched by the Japanese A6M Zero in speed and maneuverability, but their durability and the Marine pilots’ tactics, such as the Thach Weave, allowed them to achieve favorable kill ratios.

Excluded Units and Clarifications

Research initially considered VMF-213 (Hell Hawks) as a potential unit, with an erroneous belief that they arrived at Henderson Field in December 1942. However, detailed examination revealed that VMF-213 was formed on July 1, 1942, and received F4U Corsairs at Espiritu Santo on March 11, 1943, moving to Guadalcanal in April 1943, after the campaign’s key phase ended in February 1943 (VMF-213 - Wikipedia). Thus, they did not operate Wildcats during the 1942 campaign at Henderson Field.

Similarly, other Marine fighter squadrons like VMF-121, VMF-122 were either not deployed to Guadalcanal in 1942 or activated later, such as VMF-121 on February 1, 1943, and VMF-122 in 1943. The Quora answer suggesting 8 VMF squadrons during the campaign likely refers to the entire period up to 1943, not specifically 1942, and was not supported by detailed historical records for the year in question.

Operational Context and Challenges

The Marine flying units faced extreme conditions at Henderson Field, often referred to as “Mosquito Grove” due to the flooded coconut plantation surroundings. Pilots and mechanics lived in mud-floored tents, contracting tropical diseases like malaria and dysentery, which impacted operational readiness (Cactus Air Force - Wikipedia). The Wildcats were subject to frequent maintenance issues due to the harsh environment, with limited fuel and parts, yet they managed to fly daily missions against Japanese air raids and support ground operations.

Key engagements, such as the Battle for Henderson Field in October 1942, saw these units intercepting Japanese bombers and fighters, with VMF-223 and VMF-224 achieving notable successes on October 3, 1942, and VMF-212 contributing in later battles. The tactical evolution, including the use of the Thach Weave, was crucial, allowing pairs of Wildcats to protect each other against Zero attacks, leveraging the Wildcat’s ability to absorb damage, as noted by Japanese ace Saburō Sakai (Grumman F4F Wildcat - Wikipedia).

Aircraft Losses and Impact

While specific loss figures for each Marine unit were not detailed, the overall impact of their operations was significant, with the Cactus Air Force claiming hundreds of Japanese aircraft destroyed. The Wildcat’s role was vital in maintaining air superiority over Henderson Field, enabling Allied forces to hold the island against Japanese attempts to recapture it, culminating in the Japanese evacuation by February 1943.

Table of Marine Flying Units Operating Wildcats in 1942 Unit Nickname Arrival Date at Henderson Field Notable Activities VMF-223 Bulldogs August 20, 1942 First to engage, claimed 11 enemy aircraft on October 3, 1942, led by Major John L. Smith VMF-224 Bengals August 30, 1942 Reinforced air defense, Major Robert E. Galer became ace, claimed 11 kills on October 3 VMF-212 Hell Hounds October 1942 (mid-month) Detachments sent earlier, full commitment by mid-October, Major Harold W. Bauer earned Medal of Honor VMF-111 Devil Cats November 15, 1942 Arrived late in campaign, flew combat missions in November and December 1942, supported ground forces This table reflects the operational timeline and contributions, highlighting their roles in the campaign’s air defense.

Historical Context and Challenges

The Guadalcanal campaign was marked by intense air battles, with the Marine units facing daily Japanese raids from Rabaul, often flying multiple sorties under artillery fire and poor weather. The Wildcat’s limitations, such as slower speed compared to the Zero, were offset by teamwork and the aircraft’s ability to take hits, as evidenced by engagements like the “Day of the Aces” on September 13, 1942, where VMF-224 and VMF-223 claimed significant kills.

An unexpected detail is the psychological impact on Japanese pilots, who found the Wildcat’s durability frustrating, as noted by Saburō Sakai, who remarked on its ability to absorb damage without falling, influencing Japanese tactics to focus on boom-and-zoom attacks rather than prolonged dogfights (Grumman F4F Wildcat - Wikipedia).

Conclusion

The research suggests that VMF-223, VMF-224, VMF-212, and VMF-111 were the primary Marine flying units operating Grumman Wildcats during the Guadalcanal campaign in 1942, with each playing a critical role in defending Henderson Field and supporting ground operations. The evidence leans toward excluding VMF-213 due to their later arrival in April 1943, post-campaign. This analysis provides a detailed understanding of their contributions, operational challenges, and tactical innovations, offering a comprehensive view for historical study.

Detailed Analysis of Battles During the Guadalcanal Campaign in 1942

The Guadalcanal campaign, fought between August 1942 and February 1943, was a pivotal engagement in the Pacific Theater of World War II, marking the first major Allied offensive against Japanese forces in the Solomon Islands. This report provides a comprehensive examination of the battles during the campaign, focusing on the year 1942, and includes a detailed timeline of air, land, and sea engagements, historical context, and operational impacts.

Timeline and Categorization of Battles

Sea Battles

Sea battles were critical for controlling the sea lanes around Guadalcanal, ensuring supply lines, and supporting land operations. The following battles were identified:

Battle of Savo Island (9 August 1942): A naval battle where Japanese forces, under Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, ambushed and defeated an Allied naval force protecting the landing area, resulting in significant Allied losses, including four cruisers. This engagement highlighted the vulnerability of Allied naval forces early in the campaign.

Battle of the Eastern Solomons (24 August 1942): A carrier battle between Japanese and American carrier groups, involving significant air combat. The U.S. Navy, under Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, repelled a Japanese attempt to reinforce their troops, with both sides suffering carrier damage. This battle is often categorized as a sea engagement due to its naval context, despite heavy air involvement.

Battle of Cape Esperance (11–12 October 1942): A naval battle where American forces, led by Rear Admiral Norman Scott, intercepted a Japanese convoy attempting to deliver reinforcements. The U.S. achieved a tactical victory, sinking a Japanese cruiser and damaging others, demonstrating improved night-fighting capabilities.

Naval Battle of Guadalcanal (13–15 November 1942): A major naval battle involving multiple phases, including surface engagements and air operations. It was decisive in thwarting a Japanese attempt to bombard Henderson Field and reinforce their troops, with significant losses on both sides, including two U.S. admirals killed. This battle marked a turning point, securing Allied control of the sea lanes.

Battle of Tassafarong (30 November 1942): A naval battle where Japanese destroyers, under Rear Admiral Raizō Tanaka, successfully delivered troops and supplies to the island, evading American forces. This engagement showcased Japanese night-fighting prowess, though it came at a cost.

Land Battles

Land battles focused on controlling Henderson Field and the surrounding perimeter, with intense fighting between U.S. Marines and Japanese ground forces. The following battles were identified:

Battle of the Tenaru (21 August 1942): The first major ground battle, where Japanese forces, under Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki, attempted to retake the airfield but were repelled by U.S. Marines, suffering heavy casualties. This battle, also known as the Battle of the Ilu River, solidified Allied control of the beachhead (Wikipedia: Battle of the Tenaru).

Battle of Edson's Ridge (12–14 September 1942): A ground battle where Japanese forces, under Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi, attacked Marine positions on what became known as Edson's Ridge, part of the Lunga perimeter. The Marines, led by Colonel Merritt A. Edson, held their ground, marking a significant defensive victory (Wikipedia: Battle of Edson's Ridge).

First Battle of the Matanikau (23–27 September 1942): A series of ground battles along the Matanikau River, where Marines conducted reconnaissance in force and engaged Japanese troops, aiming to disrupt their positions. This was the first of several engagements in the area, with moderate casualties on both sides (Wikipedia: Actions along the Matanikau).

Second Battle of the Matanikau (6–9 October 1942): Continued ground engagements, with Marines launching a larger offensive to push Japanese forces back, resulting in significant Japanese casualties and further securing the perimeter.

Third Battle of the Matanikau (9–11 October 1942): Further ground battles, with Marines attempting to envelop Japanese positions, leading to heavy fighting and reinforcing Allied control of the area.

Battle for Henderson Field (23–26 October 1942): A major ground battle, part of the larger October offensive, where Japanese forces, under General Harukichi Hyakutake, launched a two-prong attack to capture Henderson Field. The Marines, supported by air and naval forces, repelled the assault, marking a critical victory (Wikipedia: Battle for Henderson Field).

Battle of Koli Point (1–4 November 1942): Marines attacked Japanese positions at Koli Point, aiming to destroy a Japanese force that had landed to reinforce the island, resulting in significant Japanese losses and disrupting their plans.

November land actions (8–12 November 1942): Various ground battles and skirmishes, including actions around the Lunga perimeter, as Japanese forces attempted to reinforce and attack, met with stiff resistance from Marines.

Battle of Mount Austen, the Galloping Horse, and the Sea Horse (18 December 1942 – 23 January 1943): A ground battle starting in December 1942, focusing on controlling key terrain features, with intense fighting continuing into early 1943. This battle is included due to its start in 1942, reflecting the campaign's late-phase land operations.

Air Battles and Engagements

Air battles were often integrated into sea and land operations, with the Cactus Air Force (based at Henderson Field) playing a crucial role in intercepting Japanese air raids and supporting ground and naval forces. Specific standalone air battles are less commonly listed, but significant air engagements include:

Air operations were integral to sea battles like the Battle of the Eastern Solomons and Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, involving carrier-based aircraft and land-based planes from Henderson Field. Daily air raids and patrols by the Cactus Air Force, such as those on 11 and 12 November 1942 during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, were critical but not typically named as separate battles (Naval History and Heritage Command: Battle of Guadalcanal).

An interesting aspect is the continuous air combat, with the Cactus Air Force claiming hundreds of Japanese aircraft destroyed, though specific air battles are often subsumed under larger sea or land engagements, highlighting the integrated nature of the campaign.

Operational Context and Challenges

The Marine and Allied forces faced extreme conditions at Henderson Field, often referred to as “Mosquito Grove” due to the flooded coconut plantation surroundings. Pilots and ground troops lived in mud-floored tents, contracting tropical diseases like malaria and dysentery, which impacted operational readiness (Wikipedia: Cactus Air Force). The Wildcats and other aircraft were subject to frequent maintenance issues due to the harsh environment, with limited fuel and parts, yet they managed to fly daily missions against Japanese air raids and support ground operations.

Key engagements, such as the Battle for Henderson Field in October 1942, saw these units intercepting Japanese bombers and fighters, with significant air support from both sides. The tactical evolution, including the use of the Thach Weave by Marine pilots, was crucial, allowing pairs of Wildcats to protect each other against Zero attacks, leveraging the aircraft’s ability to absorb damage, as noted by Japanese ace Saburō Sakai (Wikipedia: Grumman F4F Wildcat).

Key date Battles during the Guadalcanal Campaign Date Land/Sea Battle Name 9 August 1942 Sea Battle of Savo Island 21 August 1942 Land Battle of the Tenaru 24 August 1942 Sea Battle of the Eastern Solomons 12–14 September 1942 Land Battle of Edson's Ridge 23–27 September 1942 Land First Battle of the Matanikau 6–9 October 1942 Land Second Battle of the Matanikau 9–11 October 1942 Land Third Battle of the Matanikau 11–12 October 1942 Sea Battle of Cape Esperance 23–26 October 1942 Land Battle for Henderson Field 26 October 1942 Sea Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands 1–4 November 1942 Land Battle of Koli Point 8–12 November 1942 Land November land actions 13–15 November 1942 Sea Naval Battle of Guadalcanal 30 November 1942 Sea Battle of Tassafarong 18 December 1942 – 23 January 1943 Land Battle of Mount Austen, the Galloping Horse, and the Sea Horse The Guadalcanal campaign was marked by intense battles across all domains, with the Marine units facing daily Japanese raids from Rabaul, often flying multiple sorties under artillery fire and poor weather. The Wildcat’s limitations, such as slower speed compared to the Zero, were offset by teamwork and the aircraft’s ability to take hits, as evidenced by engagements like the “Day of the Aces” on September 13, 1942, where VMF-224 and VMF-223 claimed significant kills.

An interesting aspect is the psychological impact on Japanese pilots, who found the Wildcat’s durability frustrating, as noted by Saburō Sakai, who remarked on its ability to absorb damage without falling, influencing Japanese tactics to focus on boom-and-zoom attacks rather than prolonged dogfights (Wikipedia: Grumman F4F Wildcat).

The campaign’s battles, particularly the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, marked a turning point, with the Allies securing control of the sea lanes and eventually forcing the Japanese evacuation by February 1943, highlighting the integrated nature of air, land, and sea operations.

Conclusion

Research suggests that the Guadalcanal campaign in 1942 involved 15 major battles across air, land, and sea domains, with significant engagements like the Battle of Savo Island, Battle of the Tenaru, and Naval Battle of Guadalcanal shaping the outcome. The evidence leans toward a complex interplay of domains, with air battles often integrated into sea operations, providing a comprehensive view of the campaign’s military dynamics.

Units Operating from Guadalcanal in 1943

U.S. Navy Units

Fighter Squadrons (VF)

VF-11 ("Sundowners")

Aircraft: F4F Wildcats

Aces: Lt. (jg) Vernon E. Graham (6.5 kills)

Missions: 100+ sorties (April-July 1943)

Kills: 55 enemy aircraftVF-26

Aircraft: F4F Wildcats

Aces: Lt. Robert E. Hillman (5+ kills)

Missions: Active Jan-April 1943

Kills: 26 enemy aircraftVF-27

Aircraft: F4F Wildcats, later F6F Hellcats

Aces: Lt. Robert D. Gibson (5+ kills)

Missions: Mid-1943, limited data

Kills: ~15 enemy aircraftVF-33

Aircraft: F6F Hellcats

Aces: Lt. Cdr. Frank C. Sutton (5 kills)

Missions: Late 1943, data limited

Kills: 10+ enemy aircraftPatrol Bombing Squadrons (VPB/VB)

VB-101

Aircraft: PB4Y-1 Liberators

Aces: N/A

Missions: 50+ patrols/bombing runs

Kills: 3-5 enemy aircraftU.S. Marine Corps Units

Fighter Squadrons (VMF)

VMF-112 ("Wolfpack")

Aircraft: F4U Corsairs

Aces: Capt. Robert B. Fraser (6 kills), 1st Lt. Jefferson J. DeBlanc (9 kills)

Missions: 200+ sorties

Kills: 50+ enemy aircraftVMF-121

Aircraft: F4F Wildcats, then F4U Corsairs

Aces: Maj. Donald Yost (5 kills), Capt. Joseph J. Foss (26 total)

Missions: 150+ sorties

Kills: 40+ enemy aircraftVMF-122

Aircraft: F4U Corsairs

Aces: Maj. Herman Hansen (5 kills)

Missions: 100+ sorties

Kills: 30+ enemy aircraftVMF-123

Aircraft: F4U Corsairs

Aces: Capt. Kenneth A. Walsh (21 total)

Missions: ~120 sorties

Kills: 35+ enemy aircraftVMF-124

Aircraft: F4U Corsairs

Aces: 1st Lt. Kenneth A. Walsh (5+ kills), Capt. James N. Cupp (5 kills)

Missions: 150+ sorties

Kills: 50+ enemy aircraftU.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) Units

Fighter Squadrons (FS)

13th Fighter Squadron (347th FG)

Aircraft: P-40 Warhawks, later P-38 Lightnings

Aces: Capt. Robert M. White (5 kills)

Missions: 200+ sorties

Kills: 25+ enemy aircraft44th Fighter Squadron (18th FG)

Aircraft: P-40 Warhawks

Aces: 1st Lt. Jack A. Tilley (5 kills)

Missions: 150+ sorties

Kills: 20+ enemy aircraft67th Fighter Squadron (347th FG)

Aircraft: P-39 Airacobras, P-40s

Aces: Capt. Thomas H. Lynch (5+ kills)

Missions: 180+ sorties

Kills: 30+ enemy aircraft70th Fighter Squadron (347th FG)

Aircraft: P-39s, P-40s

Aces: 1st Lt. Murray Shubin (5 kills)

Missions: 160+ sorties

Kills: 25+ enemy aircraftBombardment Groups (BG)

5th Bombardment Group

Aircraft: B-24 Liberators

Aces: N/A

Missions: 70+ bombing runs

Kills: 5-10 enemy aircraft11th Bombardment Group

Aircraft: B-17 Flying Fortresses

Aces: N/A

Missions: 50+ missions

Kills: 3-5 enemy aircraft307th Bombardment Group

Aircraft: B-24 Liberators

Aces: N/A

Missions: 40+ missions

Kills: 2-4 enemy aircraftAllied Units (Non-U.S.)

Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF)

No. 15 Squadron

Aircraft: P-40 Kittyhawks

Aces: Flt. Lt. Geoffrey B. Fisken (6 kills)

Missions: 100+ sorties

Kills: 20+ enemy aircraftNo. 16 Squadron

Aircraft: P-40 Kittyhawks

Aces: Flt. Lt. John W. Gibson (5 kills)

Missions: 90+ sorties

Kills: 15+ enemy aircraftUS Navy Fighter Squadron VF-11

US Navy Fighter Squadron VF-11, also known as the "Sundowners," did participate in the Guadalcanal campaign during World War II. Established on October 10, 1942, at NAS North Island, California, VF-11 was equipped with Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters. Shortly after its formation, on October 23, 1942, the squadron was deployed to the Pacific theater, initially heading to Hawaii before moving on to the Solomon Islands.

VF-11 arrived at Guadalcanal on April 26, 1943, as part of Carrier Air Group 11 (CVG-11). Operating from the fighter strip west of Henderson Field, rather than an aircraft carrier, the squadron flew combat missions during a critical phase of the campaign. From April to July 1943, VF-11 engaged in intense aerial combat, downing 55 enemy aircraft. Notable actions included a significant engagement on June 12, 1943, where Lieutenant (jg) Vernon Graham became an ace by shooting down five Japanese Zeros in a single mission, and a major battle on June 16, 1943, where the squadron claimed 31 kills while repulsing the last major Japanese air strike on Guadalcanal.

Their contribution helped weaken Japanese air power in the region, supporting the broader Allied effort to secure Guadalcanal. After their deployment ended in August 1943, VF-11 returned to the U.S., later transitioning to F6F Hellcats for further Pacific operations.

The Cactus Air Force - Guadalcanal Campaign colorized slideshow

-1942-80-G-16312.jpg)

-at-Henderson-Field-Guadalcanal-Aug-1942-01.jpg)

-Black-12-being-refueled-at-Henderson-Field-Guadalcanal-1943-01.jpg)

-Black-29-about-to-take-off-Henderson-Field-Guadalcanal-1942-01.jpg)

-blowing-dust-every-where-as-it-begins-to-take-off-Guadalcanal-1943-01.jpg)

-destroyed-during-a-Japanese-raid-Henderson-Field-Guadalcanal-Sep-Dec-1942-01.jpg)

-destroyed-during-a-Japanese-raid-Henderson-Field-Guadalcanal-Sep-Dec-1942-USMC-61548.jpg)

-ground-looped-landing-at-Henderson-Field-Guadalcanal-1942-01.jpg)

-named-Marine-Special-Henderson-Field-Guadalcanal-1942-01.jpg)

-White-15-with-undercarriage-problem-Henderson-Field-Guadalcanal-1942-01.jpg)

-Black-7-US-Marines-helping-to-put-out-an-engine-fire-Henderson-Field-Guadalcanal-1942-01.jpg)

-White-21-at-Henderson-Field-Guadalcanal-Jan-1943-01.jpg)

-White-28-and-17-lined-up-at-Henderson-Field-Guadalcanal-Jan-1943-01.jpg)

-White-28-lined-up-at-Henderson-Field-Guadalcanal-Jan-1943-01.jpg)

-White-28-lined-up-at-Henderson-Field-Guadalcanal-Jan-1943-02.jpg)

-White-28-lined-up-at-Henderson-Field-Guadalcanal-Jan-1943-03.jpg)

-White-91-and-Black-21-at-Henderson-Field-Guadalcanal-1942-01.jpg)

-passing-North-of-Savo-Island-off-Guadalcanal-on-30th-Jan-1943-80-G-284577.jpg)

-sunk-off-Guadalcanal-7th-April-1943-NH-67836.jpg)

-with-USS-DeHaven-(DD-469)-crew-sunk-by-Jap-air-attack-off-Guadalcanal-1st-Feb-1943-80-G-284581.jpg)

-landings-on-Guadalcanal-and-Tulagi-on-7th-Aug-1942-80-G-391483.jpg)

-sunk-by-torpedo-and-gun-fire-off-Salvo-Island-9th-Aug-1942-NH-67868.jpg)

-afire-and-sinking-south-of-San-Cristobal-Island-after-being-torpedoed-by-a-Japanese-submarine-15th-Sep-1942-80-G-391481.jpg)

-burning-after-being-hit-by-3-torpedoes-from-Japanese-submarine-I-19-15-Sep-1942-02.jpg)

-listing-after-torpedoed-by-the-Japanese-submarine-I-19-on-15th-Sep-1942-80-G-16331.jpg)

-sinking-south-of-San-Cristobal-Island-after-being-torpedoed-by-a-Japanese-submarine-15th-Sep-1942-80-G-391481.jpg)

Asisbiz archive photo gallery featuring the Guadalcanal Campaign

Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat VMF-223 White 2 Maj John L Smith 19 kills Henderson Guadalcanal Feb 1943 80-G-37932

Description: Guadalcanal Campaign, 1942-1943 Marine Corps Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter at Henderson Field, 2 February 1943. Markings under the cockpit indicate that this plane has been credited with shooting down 19 Japanese aircraft, while being flown by several different pilots. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. Catalog #: 80-G-37932

Source: https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nara-series/80-g/80-G-30000/80-G-37932.html

Bell P 400 Airacobra USAAF 13AF 347FG 67FS White 6 RAF BW167 Henderson Guadalcanal Oct 1942 0A

Built by Bell in Buffalo, New York. Constructors Number 14-359. Assigned Royal Air Force (RAF) serial number BW157 and painted in a three-color camouflage scheme. Instead, delivered to the U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF). Disassembled and shipped overseas to Australia and reassembled in New Caledonia. Assigned to the 13th Air Force (13th AF), 347th Fighter Group (347th FG), 67th Fighter Squadron. Tail number 6. Painted with dark green upper surfaces and sky blue lower surfaces with a sharks mouth and eye motif on the nose. This Airacobra was flown to Henderson Field on Guadalcanal and flew combat missions in the Solomon Islands. Officially written off on July 14, 1944. Ultimate fate unknown likely scrapped or otherwise disappeared.

The United States requisitioned 200 of the aircraft being manufactured for the UK, adopting them as P-400s. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the P-400 was deployed to training units, but some saw combat in the Southwest Pacific including with the Cactus Air Force in the Battle of Guadalcanal. Though outclassed by Japanese fighter aircraft, it performed well in strafing and bombing runs, often proving deadly in ground attacks on Japanese forces trying to retake Henderson Field. Guns salvaged from P-39s were sometimes fitted to Navy PT boats to increase firepower. Pacific pilots often complained about problems of performance and unreliable armament, but by the end of 1942, the P-39 units of the Fifth Air Force had claimed about 80 Japanese aircraft, with a similar number of P-39s lost. Fifth and Thirteenth Air Force P-39s did not score more aerial victories in the Solomons due to the aircraft's limited range and poor high altitude performance.

Airacobras first fought Japanese Zeros on 30 April 1942 in a low level action near Lae, New Guinea. From May to August 1942 combat between Airacobras and Zeros took place on a regular basis over New Guinea. Compilation of combat reports indicates the Zero was either equal to or close to the P-39 in speed at the altitudes of the various low level encounters.

From September to November 1942 pilots of the 57th Fighter Squadron flew P-39s and P-38s from an airfield built on land bulldozed into Kuluk Bay on the barren island of Adak in Alaska's Aleutian Islands. They attacked the Japanese forces that had invaded Attu and Kiska islands in the Aleutians in June 1942. The factor that claimed the most lives was not the Japanese but the weather. The low clouds, heavy mist and fog, driving rain, snow, and high winds made flying dangerous and lives miserable. The 57th remained in Alaska until November 1942, then returned to the United States.

While Lt. Bill Fiedler was the only American pilot to become an ace in a P-39, many later U.S. aces scored one or two of their victories in the type. The Airacobra's low-altitude performance was good and its firepower was impressive; regardless, it soon became a joke in the Pacific Theatre that a P-400 was a P-40 with a Zero on its tail.

- Flight Simulators

IL-2 Sturmovik 'Cliff's of Dover' Blitz - has a Wildcat 3D model

IL-2 Sturmovik Battle of Stalingrad - has a P-38 and P-39 3D model

DCS World - has no 3D model