Photographic Information

USN Composite Squadron Thirty Six VC-36 colorized slideshow

-ready-to-land-Feb-1944-80-G-269036.jpg)

-ready-to-land-Feb-1944-ASC.jpg)

-in-the-North-Atlantic-12th-April-1944-80-G-269035.jpg)

-in-the-North-Atlantic-12th-April-1944-ASC.jpg)

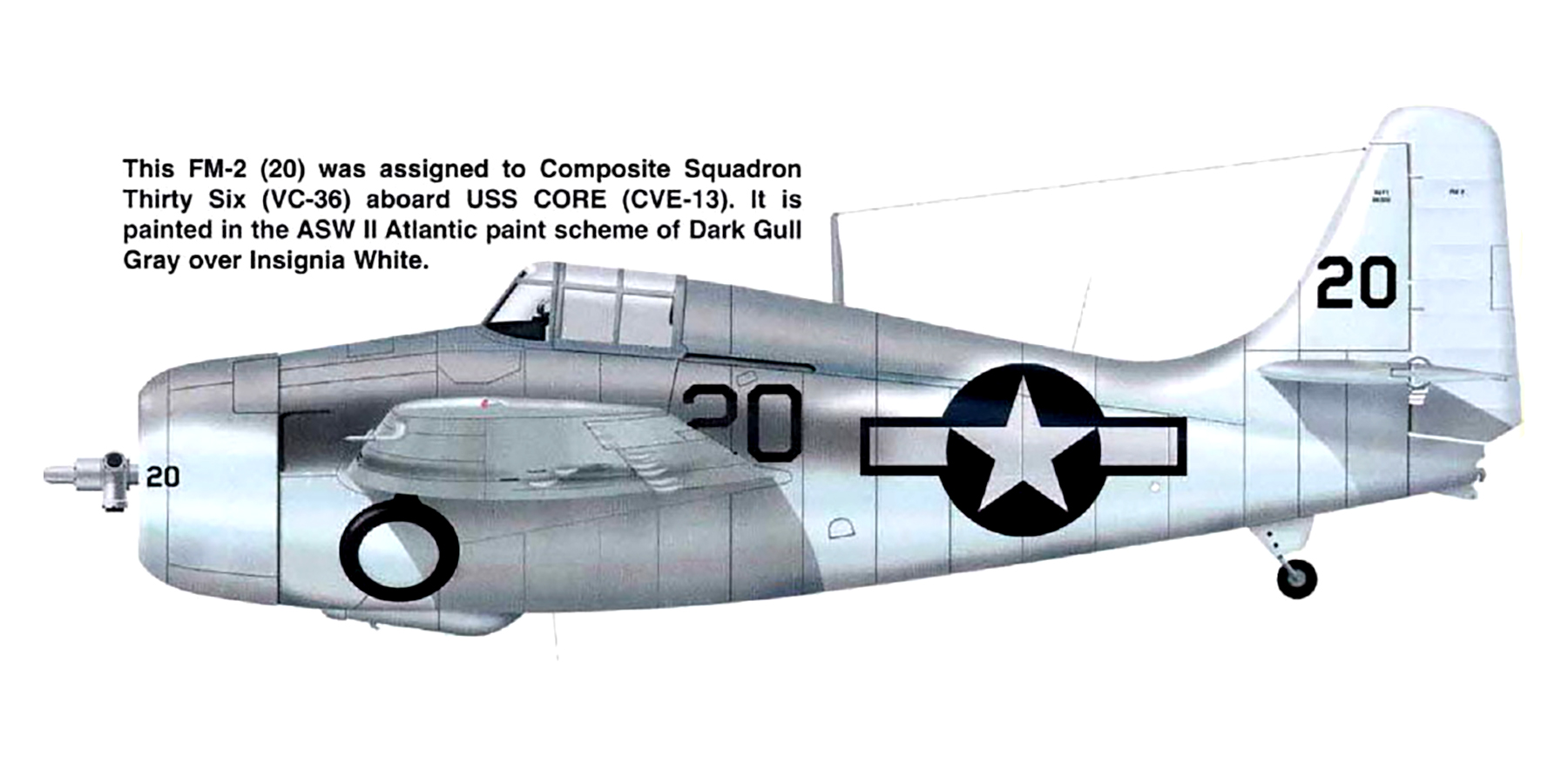

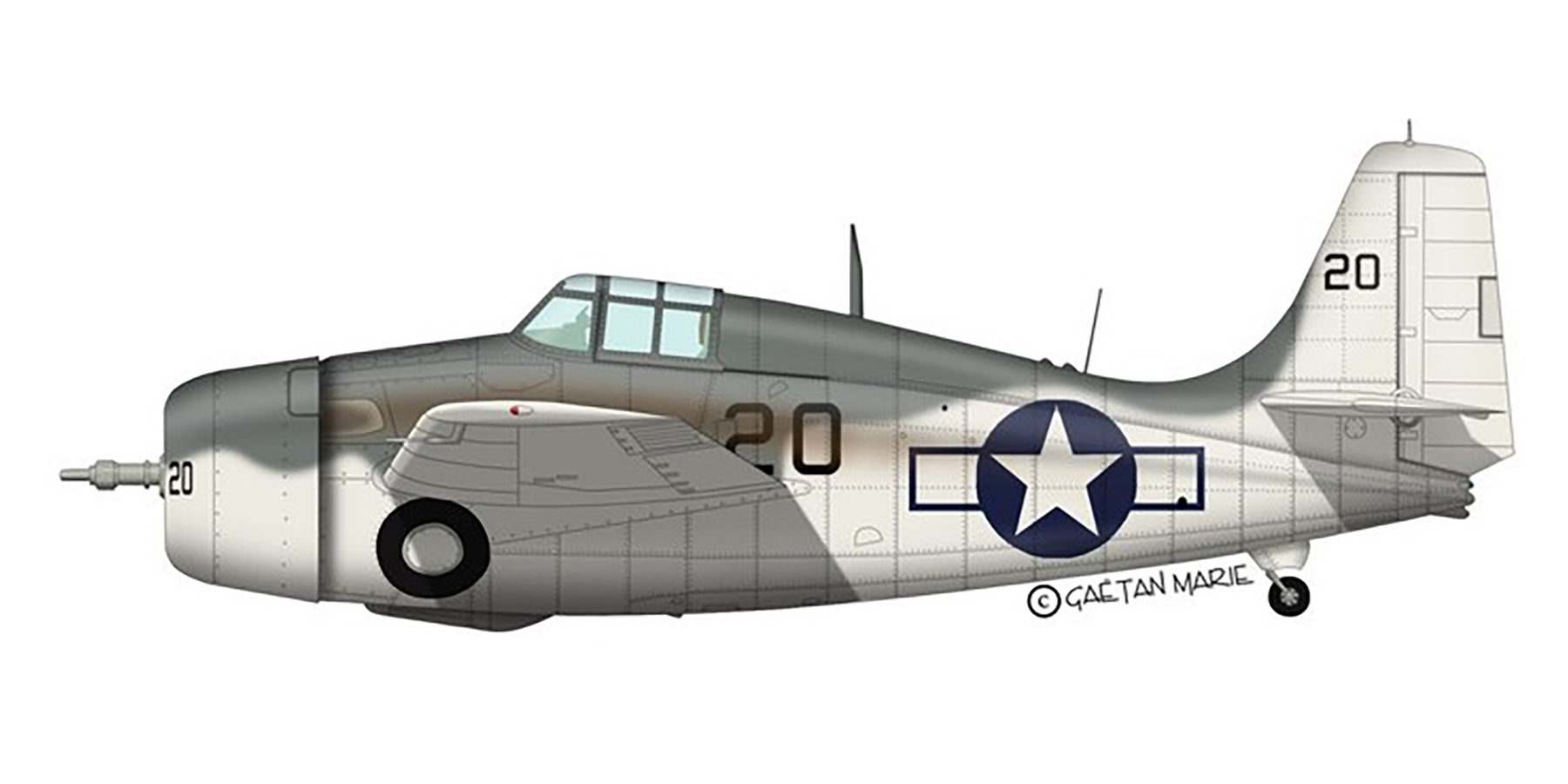

FM-2 Wildcat VC-36 Black 20 catapult luanched from CVE-13 USS Core April 1944 80-G-269035

Description: General Motors FM-2 Wildcat fighter Is catapulted from USS Core (CVE-13), in the North Atlantic, 12 April 1944. Taken by Photographer's Mate N.H. Seehafer. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. Catalog #: 80-G-269035

Source: https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nara-series/80-g/80-G-260000/80-G-269035.html

FM-2 Wildcat VC-36 Black 17 from CVE-13 USS Core ready to land Feb 1944 80-G-269036

Description: General Motors FM-2 Wildcat fighter Flies near USS Core (CVE-13), during operations in the North Atlantic, 12 April 1944. Plane has its landing gear and tailhook down, in preparation for landing on board. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. Catalog #: 80-G-269036

Source: https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nara-series/80-g/80-G-260000/80-G-269036.html

USS Core CVE-13 photo gallery and aircraft carrier history

U-67 sunk by VC-13 aircraft from USS Core

July 16, 1943

German Submarine U 67 sunk by aircraft from USS Core (CVE 13) 16th July 1943

German Submarine U 67 sunk by aircraft from USS Core (CVE 13) 16th July 1943

The attacking section of 1 TBF-1C, pilot Lt.(jg) R. W. Hayman, UNSR, and 1 F4F-4, pilot Lt. Comdr. C. W. Brewer, USN, was flying the second leg of an offensive search into an area reported by COMINCH to contain a refueling concentration. Overcast averaged .5, with scattered showers, though the area immediately over the scene of attack was clear. Visibility averaged 10 miles except in rain squalls. The sea was very rough, with a wind of 32K. The section had previously been flying on course 0000 at 6000' searching visually, but had reduced to 4000' to go under a cloud. Emerging from under the cloud, the submarine was sighted by the TBF pilot approximately 300 off his starboard bow, distant 3 miles. Submarine was black fully surfaced, on course 3300 headed directly into the wind, and was making very little more than steerage way.

The F4F-4 was flying close aboard and immediately caught the TBF pilot's hand signal, located the submarine and started a strafing run, attacking the submarine from the port quarter, 300 from astern. Sun on the port quarter made this run almost directly from out of the sun. Fire was opened at 1,000 yards and tracers were seen by accompanying TBF's crew to ricochet from the deck and conning tower. Approximately 1,000 rounds of ammunition were expended. Fire was concentrated on C/T as the after guns appeared not to be manned. When F4F was at 500' a violent red flame was seen to break out, which completely filled the conning tower and extended aft to the upper gun platform. No anti-aircraft fire was experienced. Pulling out of the strafing run, F4F-4 turned left and gained a position which afforded unobstructed visibility of the depth charge attack.

The TBF had meanwhile turned right to lose altitude and gain a more favorable position for attack, the angle of direct attack being too steep. Attack was made from almost directly astern in a final glide of approximately 100. The pilot expended 40 – 50 rounds from each gun in strafing during approach. Bombs were released from 175' altitude, course 3300, speed 240K. Bombs entered the water 100' and 170' over and slightly to the left of submarine's course, probably due to plane being in a left skid at the time. (See photo of LTJG Hayman's attack) The tip of the submarine's bow was obscured by the water thrown up by the explosion.

The submarine proceeded on into the depth charge disturbance. Some 30 seconds following the depth charge explosion, the submarine suddenly rolled over 600 to port. Very shortly thereafter the bow and conning tower disappeared, leaving the stern above the surface at an angle of 300. Twenty to forty feet of stern was visible for 20 to 30 seconds, the length visible being varied by the waves. The stern then slowly disappeared. During this time the TBF had made a turn to the left to gain position for an attack with a MK 24 mine, taking pictures meanwhile.

Thirty seconds after the stern disappeared the TBF made another run upwind along the course of the submarine, dropping a MK 24 mine at the center of the disturbance left by the disappearing stern. The mine entered the water, ran straight ahead true and then made a sharp turn to the right. Approximately two minutes thereafter, the pilot and radioman observed a shock wave and a white flash (“as if some one had turned on a flash light under water') 300 – 400' forward and to starboard of the point of the mine's entrance. This shock wave developed into - 1 - ENCLOSURE (A) a symmetrically round area of green water and air bubbles (as opposed to the disturbance left by breaking rollers). This symmetrical area faded out within a minute or two in the heavy seas, but the disturbance is clearly discernable in the photographs. No further evidence was observed by the planes, which remained on station for 2 hours and fifteen minutes and kept the position marked with dye markers and smoke floats. Sea was so rough that dye markers which usually persist for a matter of hours were very nearly obscured in fifteen minutes.

The USS CORE maintains a 24-hour guard on the two (2) high frequencies of the area, and in addition, two (2) high frequencies of adjacent are as defined in CSP 1774(A). Further, from one (1) hour prior to darkness until daylight the USS CORE guarded frequencies 385, 396, 437, and 490 kilocycles, and searched continuously as follows: USS GREENE 200-350 kilocycles; USS BELKNAP 350-500 kilocycles; USS GOLDSBOROUGH 500-650 kilocycles. No transmissions which might possibly have emanated from the attacked submarine were intercepted.

U-378 sunk by VC-13 aircraft from USS Core

October 20, 1943LT Williams (Left) discusses attacking 3 U-boats in four days with VC-13 CO, LCDR Charles Brewer (Center - later lost in action in the Pacific), and LTJG James F. Scoby (Right - the pilot of the other attacking TBF-1 during the sinking of U-487) - note the VC-13 squadron insignia on the engine cowling of the F4F-4 Wildcat fighter U-487 sunk by VC-13 aircraft from USS Core on July 13, 1943

COMPOSITE SQUADRON THIRTEEN

July 13, 1943.

Two sections, each consisting of one TBF-1 and one F4F-4, were launched at 1253 - July 13, 1943, to search ahead of Convoy GUS 9 to a distance of 200 miles. The weather was variable. Visibility ranged from 8 to 15 miles. The sea was smooth, with occasional white caps. Could cover varied from 0.3 to 0.7. Section #1 composed of Lieutenant R. P. Williams, USNR, in the TBF, and Lt.(jg) E. H. Steiger, USNR, in the fighter, started their return leg at an altitude of 7,000 feet. The TBF was using radar intermittently whenever local cloud conditions and visibility warranted. Toward the end of the leg the radar was secured, and the section dropped down to 5,500 feet to keep below a cloud layer.

About eight minutes later, at 1521, the TBF's turret gunner noticed a white wake about 10 miles distant on the plane's quarter. Both planes turned to port as soon as the TBF's pilot, Lieutenant Williams, saw the wake. Williams, using cloud cover during his approach, ascertained that a fully surfaced submarine was causing the wake. Its course was approximately 1300T, and speed between 12 and 14 knots. That particular area had about 0.3 cumulus cloud cover with the base around 2,500 feet. When beyond cloud cover, Williams signaled Steiger to commence a strafing run. Steiger broke off immediately and strafed the submarine, approaching on its starboard bow. Williams commenced a bombing run as soon as he had attained favorable position on the submarine's starboard quarter. During his approach he noticed a man running across the deck forward of the conning tower as if to man a gun. Williams released a stick of four Mark 47 depth bombs, set for a depth of 25 feet about 10 seconds after Steiger had completed his strafing run. Release was made at about a 250 foot altitude, while the plane was on a 250 glide. The intervalometer was set to space the bombs 70 feet apart at a speed of 220 knots. Williams radioman photographed the resulting explosions through the tail-gun aperture. (All TBF tail guns have been temporarily removed to facilitate photography from the radioman's station). The developed picture (Photo #1 enclosed) indicated that the explosions of the first and second bombs straddled the U-boat's bow about 35 feet forward of the conning tower.

Both planes pulled up to 3500 feet and circled to observe the results of their attack. The submarine immediately went into a tight right-hand circle and gradually slowed to a stand-still. Oil leaking from it completely covered the area bounded by the submarine's turning circle. Meanwhile the crew manned its guns and commenced 'AA' fire. Williams observed that the bursts were consistently below and usually behind the aircraft circling at 3,500 feet. Radio contact was established with the ship and details of the attack were transmitted. Shortly thereafter, Williams indicated to Steiger that he wished to make another pass over the submarine for the purpose of taking additional photographs. Steiger made a second strafing run, closely followed by the TBF. It later developed that no pictures were obtained on that run.

As soon as word was received aboard the ship, the U.S.S. BARKER was immediately ordered to the scene of the attack and additional planes were launched. Four TBF's manned by Lt.(jg) J.F. Schoby, USNR., Lt.(jg) C.E. Lair, USNR., Lt.(jg) W.V.A. Wilson, USNR., and Lt(jg) H.W. Hayman, USNR, were catapulted. They were followed immediately by Lt. Comdr. C. W. Brewer, USN., in an F4F-4. While these planes were enroute Williams noticed white water aft of the submarine and asked Steiger by radio if he had sufficient ammunition for another

ENCLOSURE (A) run to investigate submarine's course of action. Steiger replied that he had 'only one gun left, but would make the run'. On this run, when only a few hundred feet from the U-boat's port quarter, Steiger's plane suddenly swerved to the left, its nose dropped, and it plunged into the water about 100 feet off the submarine's port bow. A thorough search of the area made later revealed no trace of the pilot or plane.

Brewer arrived in time to see the splash of Steiger's plane as Williams informed the ship that the submarine 'had gotten one of our planes'. Brewer passed the word by radio to the oncoming TBF's that he was starting his strafing run. Approaching the submarine's stern down-sun from cloud cover he expended around 1200 rounds of .50 caliber ammunition. Lt.(jg) J. R. Bronstein, USNR, the F4F-4 member of the #2 section on search, had just arrived in the vicinity and started a strafing run from the U-boat's starboard beam. He held his fire while Brewer passed over the submarine, and was interrupted a second time as Lt.(jg) Schoby, in the first TBF to arrive from the ship, approached from the submarine's starboard bow. Diving at a 200 angle, speed 245 knots, Schoby dropped four Mark 47 depth bombs from an altitude of 100 feet. All explosions were close aboard or under the submarine, from starboard bow to port quarter (Photograph # 3 enclosed). Depth and intervalometer setting were identical to those used by Williams. The water thrown by the explosions appeared to lift the U-boat vertically about 10 feet before completely enveloping it. When the U-boat could next be seen some 30 feet of its stern protruded from the water at a 450 angle. About five seconds later it slid under the surface.

Immediately after the sinking approximately 35 survivors, the majority clustered around two dark gray life rafts, were counted in the water. There was a minimum of debris. Visible were a few small irregular objects and two large life rafts, almost entirely submerged, in addition to those used by the survivors. About one hour later, an oil slick covered an area roughly a mile square. Brownish scum, apparently a result of the depth charge explosion, accumulated near the down-wind edge of the slick, and a small area near where the submarine sank was colored a light apple-green.

Brewer and Hayman remained in the area to guide the destroyer to the survivors and to give it air protection while it recovered them. (For details of rescue operations, and for pertinent comments by survivors, see enclosure (B) and (C) ). All other planes were ordered back to the ship at 1635, Brewer and Hayman returning aboard at 1850.

Web reference: http://www.uboatarchive.net/Uboatlist.htm

Black May - The Tide Turns in the Battle of the Atlantic

There were many factors that caused the sudden turn of fortune in the Allies’ favor during May 1943, and to say that any one of them was the decisive factor would not be accurate. However, to briefly re-cap the Battle of the Atlantic prior to May 1943, the battle had see-sawed throughout the course of the war to that point. In the months after the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, German U-boats had great success (the “First Happy Time”), but an insufficient number of submarines at the start of the war was a major factor in Great Britain’s ability to survive the first year of the conflict despite heavy losses of both merchant ships and warships. However, effective use of convoys, improved ASW sensors, weapons, and tactics enabled the British to decrease their losses and make the U-boats pay a higher price. Nevertheless, the period 1940 to 1941 was very desperate for the British as the island nation faced acute shortages of just about everything, including fuel oil and food, which at times reached critical levels.

When the United States entered the war after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Germany immediately (unlike in World War I) sent U-boats to attack shipping right off the U.S. east coast. With the United States unprepared for the onslaught of “Operation Drumbeat,” the result was unprecedented carnage at sea. For the U-boats, the first months of 1942 were the “Second Happy Time.” For the Allies, they were a near-disaster that cost more lives, and many more ships, than Pearl Harbor. As the United States got its act together along the eastern seaboard in the late spring of 1942, the Germans shifted their operations to the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, with initial great success. In the summer of 1942, Arctic convoy PQ-17 was also a disaster in which most of the ships carrying critical supplies to Russia were lost. (Although it is true that the amount of war material produced by the Soviet Union by itself dwarfed that provided to the Soviet Union by the United States and United Kingdom, the material that did get through—at great cost—came at a critical time when the Soviet Union was hanging on by a thread. Had it not been for the Allied supplies, the Soviet Union might not have survived long enough to build the hordes of tanks that eventually took the war to Berlin.)

Throughout late 1942 and early 1943, convoys fought their way across the Atlantic, and although U-boat losses increased, they were still manageable and the submarines were still inflicting serious losses on the convoys. However, increasingly capable and longer-range Allied air cover made operating in certain areas extremely dangerous for the U-boats, and the mid-Atlantic gap, where convoys were most vulnerable because they had no air cover, was getting smaller and smaller. The peak of pitched Atlantic convoy battles occurred in March 1943, when U-boats sank 567,000 tons of Allied shipping. (Note that statistics in the Battle of the Atlantic should be taken with a grain of salt, because many different sources use different frames of reference for how they count things.) Nevertheless, a lot of Allied shipping went to the bottom in March 1943, and the rate of loss would make a build-up for an early Allied invasion of Europe very problematic. In the space of one ten-day period in March, 40 Allied merchant ships would be sunk by U-boats in the Atlantic.

One key factor in the Battle of the Atlantic was the continuing war for intelligence by both sides, and, as in the battles at sea, it was very much a back-and-forth affair, sometimes without either side knowing it. One reason for the Germans’ success was that their naval radio intelligence and code-breaking organization, “B-Dienst,” was very good, and, from 1941 into most of 1943, the Germans were breaking and reading the British convoy codes fast enough to take operational action (although, like the Allies, the Germans were very careful in how they used code-breaking intelligence so as to not give away the fact that they were doing it). In fact, the British had no idea the Germans were reading their convoy-routing traffic. The British finally changed their convoy-routing code in June 1943 at the urging of the U.S. Navy cryptologic organization, OP20G.

The British had good initial success against the German Enigma encoding machine (which was an extraordinary electro-mechanical device that was close to impervious to being broken, even if a machine was captured). Nevertheless, the British had caught some early breaks with captured code books and development of “cribs” resulting from rare but periodic German communications security lapses that enabled the British to read a fair amount of Enigma code traffic at a useful pace, which they shared with the U.S. However, in February 1942, the German navy added a fourth rotor to their Enigma machines, which resulted in an astronomical (literally) increase in possible numeric combinations, making it impossible to break except by developing electro-mechanical devices even more sophisticated (and costly) than the Enigma machines. The new naval Enigma system was known as “Triton” by the Germans, and “M4 Shark” by the British. Partly as a result of the loss of ability to read Enigma traffic, convoy losses in the Atlantic in the latter half of 1942 were three times that of the same period in 1941.

The counter to the Enigma were massive machines, known as “bombes,” which were a marvel of technology at the time, because they required extremely high quality control for components, which were in constant high-speed motion in order to brute-force their way through many millions of possible combinations. Even then, the machines, even when operating in large numbers, could not do it themselves. Code-breaking art by skilled cryptanalysts was still required to give the machines a chance of success. Nevertheless, with the advent of the four-rotor Enigma in the German navy, Britain’s best source of Intelligence mostly dried up. (The German army and air force kept using the three-rotor device, so the Allies had much greater success breaking their communications.) The British could still read a German weather signals code and gain some intelligence about U-boat operations, but on 10 March 1943, the Germans switched to a new set of weather codes, and the British lost even that tenuous hold, which was one key factor in the high convoy loss rates in the latter half of March 1943.

Meanwhile, while the British were having serious production difficulties developing and building bombes (and enough of them) to work the four-rotor Enigma, the U.S. Navy had embarked on a hugely expensive crash program to do the same thing. In fact the U.S. bombe effort was given the same resource priority as the Manhattan Project (atom bomb development) and the technological challenges were arguably as great. The bombes were developed at the U.S. Naval Computing Machine Laboratory on the National Cash Register (NCR) compound in Dayton, Ohio. Cost overruns in the program were in the millions (in 1942 dollars). The first two “Desch” bombes, known as Adam and Eve, followed by Cain and Abel, were all prone to serious technical difficulties. For many months it appeared as if the Navy was pouring huge sums of money and resources (advanced materials) down a rat hole, all to the frustration of U.S. Navy cryptologist, who for the first year of the war were highly dependent on British intelligence.

Of note, the type of code-breaking employed against the Japanese was completely different than that employed against the Germans. The Japanese used old-fashioned paper-and-pencil code systems and didn’t have Enigma machines or an equivalent (except for the diplomatic “Purple” code) in any kind of scale operation. However, success against the Japanese contributed nothing to success against the Germans. Nevertheless, by the spring of 1943, the United States had overcome most of the technical challenges of the bombes, and was starting to build them in large numbers (hundreds would be required to perform the necessary calculations). The Navy also enlisted a small army of several hundred women (WAVES) to mind the hundreds of bombes that were put in operation in a commandeered women’s college on Nebraska Avenue in Washington, DC (in what for many years after the war was the headquarters of Naval Security Group). This duty was not without danger, as the bombes were prone to throwing metal components at high velocity. In theory, the WAVES did not know the true purpose of the machines they were minding, other than that it was a extremely important top secret program to which they were sworn to a lifetime of secrecy (and the WAVES kept their oath until the end). Although the U.S. Navy bombes didn’t play a significant role in “Black May,” by the end of June 1943 they were having significant effects and results. For the duration of the war, the U.S. Navy code-breaking effort emerged into the lead against the Germans. (More on this in a future H-gram.)

Like the British, the Germans didn’t think their codes were vulnerable either. As a result, the Germans were prolific communicators, which created vulnerability through techniques of traffic analysis and radio direction finding even during periods when the Allies could not read the contents of the messages. Grossadmiral Karl Dönitz, who had moved from commander of the German submarine force to supreme commander of the German navy (after Grossadmiral Erich Raeder had been relieved when Hitler became unenthused about the performance of the German surface navy), was in frequent communications with German U-boats, providing locations and routing of Allied convoys, and forming wolf packs of multiple submarines to attack the convoys. The Allies were trying just as hard to route the convoys away from where the wolf packs were forming, and the failure to do so in late March 1943 was a factor in the high convoy losses.

Led by the British, the Allies embarked on a crash program for high frequency radio-direction finding (HFDF) on both ships and aircraft, with such considerable and rapid success that the Germans did not really grasp their vulnerability to the technology. The Germans ascribed the sudden appearance of Allied anti-submarine ships and aircraft in unexpected places to a wide variety of other factors, particularly airborne radar and a belief that the British had developed an infrared (IR) sensor (abetted by false reports deliberately planted by the British as deception), which led the Germans to invest considerable resources in special paint for their submarines to imitate the optical properties of sea water, as well as a crash German program to develop IR sensors of their own, with some limited progress before the war ended.

For all the importance of intelligence in the overall Battle of the Atlantic, during the turning point in May, Allied ntelligence capability against the U-boats was at the weakest point of the entire war. Fortunately several other factors and technologies came to fruition at the same time, resulting in a radical shift of fortune.

The first factor was Allied air power, with significantly greater numbers of longer-range aircraft operating from increasing numbers of bases around the Atlantic, as well as from a growing number of small escort carriers, such as the USS Bogue (CVE-9), which played a significant role in operations against German submarines in May 1943. The modified, very long-range B-24 Liberator bombers closed the mid-Atlantic gap, and the escort carriers could provide near continues air cover to the convoy.

The U-boats were acutely vulnerable to aircraft attack, and the Germans even developed “flak” U-boats, designed with a heavy defensive anti-aircraft armament intended to duke it out on the surface with aircraft. The Allies received a rude shock (due to surprise) during the first encounter with a flak U-boat, before they quickly adapted and it became readily apparent that this was not one of the Germans’ better ideas. The British, in particular, also resumed air attacks (after early heavy losses) against U-boats returning to their bases in occupied France on the Bay of Biscay. The last few miles of a U-boat patrol quickly become the most dangerous, and many were lost almost within sight of the safety of their massively reinforced U-boat pens. Increasingly equipped with airborne radar, ASW aircraft became significantly more dangerous and could attack at night when the U-boats preferred to surface to recharge their batteries. The preferred tactic by wolf packs was also a night surface attack; taking away the U-boats’ sanctuary in the darkness had a major adverse effect on U-boat success and survival.

Another factor was sheer numbers. The anti-submarine production effort was given top priority (and U.S. Navy commanders felt the resulting shortages first-hand during the brutal battles around Guadalcanal in late 1942) but, by 1943, Allied (primarily U.S.) shipyards were cranking out more of everything: ships, aircraft, weapons, sensors. Even during the worst of the U-boat attacks, Allied ship building was keeping pace with losses (sometimes barely) while German shipyards were also keeping pace with their submarine losses. By May 1943, those curves had changed radically. U.S. shipyards were producing many more ships than the Germans could sink, and the Germans were losing more submarines that their shipyards could replace—hence, Dönitz’s recall order on 24 May 1943. The Germans didn’t make a concerted effort to resume submarine operations in the Atlantic until the fall of 1943, and from then on they were almost constantly on the defensive.

Rapidly improving Allied technology, and the tactics to use it effectively, coupled with advances in scientific operational analysis, also reached a key inflection point in May 1943. The new U.S. Navy short- range communications system, “Talk-Between Ships” (TBS), developed just before the start of the war, represented a significant advance over the CW 936 radio-telephones that had proved very effective when first introduced in World War I. New weapons technology included better sonar, the advent of sonobouys, and FIDO, which was termed the Mark 24 mine, but was actually a U.S. air-dropped passive acoustic homing ASW torpedo, introduced in March 1943.

Another weapons technology was the proliferation of the British-designed forward-throwing ASW Hedgehog depth bomb aboard both British and U.S. ships. (In the Pacific, in May 1944, USS England (DE-635) sank six Japanese submarines in as many days using Hedgehog). With the Hedgehog, the attacking surface ship did not have to first steam over the contact and drop depth charges in her wake, thus allowing the submarine much less time to take evasive maneuvers. Quickly recognizing the deadly threat posed by the Hedgehog (one in five Hedgehog attacks resulted in a kill, compared to one out of 80 for conventional depth charges), the Germans introduced the Falke (“Falcon”) acoustic homing torpedo in mid-1943, which was in turn countered by the Allied Foxer noisemaking decoy. The Germans also developed the Wanze (“Tick”) radar-warning device to try to counter increasingly deadly attacks by Allied aircraft equipped with microwave anti–surface vessel (ASV) radar. The Allies countered with radars at a frequency Wanze could not detect. In early May 1943, this 10-centimeter radar aboard aircraft detected all 26 attempts by U-boats to attack convoy ONS 5, which were driven off.

Greatly improved Allied tactics were primarily a function of hard-won lessons learned and experience. Commanders and crews had simply gotten better than they were earlier in the war. Scientific analysis was also used to refine tactics. With more assets, independent support groups could be placed at strategic points along the convoy routes, where they could more rapidly reinforce a convoy’s organic escorts in the event the convoy came under wolf-pack attack. The German wolf-pack tactics (later used with great effect by U.S. submarines against the Japanese) and Allied support group tactics are arguably early examples of “swarm” tactics.

Allied operational capability had so improved by mid-1943 that it would have actually made more sense to draw the U-boats to the convoy rather than using Ultra (broken Enigma traffic) to avoid them, under the theory that the more U-boats that attacked, the more that could be sunk. Nevertheless, U.S. and British commanders balked at the idea of using convoys as “bait,” instead choosing to employ hunter-killer task groups, often driven by intelligence on U-boat locations. Although use of the hunter-killer groups was raised to a fine art, they were resource-intensive and less efficient than letting the U-boats come to the target, but much better for the morale of those on the troopships.

Another major development in May 1943 was the creation of the U.S. Tenth Fleet on 20 May. CNO/COMINCH Admiral King directed that the responsibilities of technological development, scientific operational analysis, ASW doctrine, and training be combined in one command, along with significant intelligence capability. Although the Tenth Fleet did not have its own forces, it would serve as the central command responsible for protecting convoys and hunting down U-boats. Despite being stood up too late to effect the convoy battles in early 1943 or the turning of the tide, Tenth Fleet would have significant effect on the remainder of the Battle of the Atlantic, and would serve as a forerunner of the operational intelligence (OPINTEL) concept that served the U.S. Navy throughout the Cold War, integrating all types of intelligence into a very close operational cycle.

(Sources include The Secret in Building 26: The Untold Story of America’s Ultra War Against the U-boat Enigma Codes, by Jim DeBrosse and Colin Burke, 2004, “Turning Point in the Atlantic” by Commander In H. Ha, USN, in the April 2018 issue of Naval History magazine, and Information at Sea: Shipboard Command and Control in the U.S. Navy from Mobile Bay to Okinawa by Timothy S. Wolters, 2013, as well as a host of U-boat books in my personal library.)

Source: https://www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-019/h-019-4.html

Bibliography:

Magazine References: +

- Airfix Magazines (English) - http://www.airfix.com/

- Avions (French) - http://www.aerostories.org/~aerobiblio/rubrique10.html

- FlyPast (English) - http://www.flypast.com/

- Flugzeug Publikations GmbH (German) - http://vdmedien.com/flugzeug-publikations-gmbh-hersteller_verlag-vdm-heinz-nickel-33.html

- Flugzeug Classic (German) - http://www.flugzeugclassic.de/

- Klassiker (German) - http://shop.flugrevue.de/abo/klassiker-der-luftfahrt

- Le Fana de L'Aviation (French) - http://boutique.editions-lariviere.fr/site/abonnement-le-fana-de-l-aviation-626-4-6.html

- Le Fana de L'Aviation (French) - http://www.pdfmagazines.org/tags/Le+Fana+De+L+Aviation/

- Osprey (English) - http://www.ospreypublishing.com/

- Revi Magazines (Czech) - http://www.revi.cz/

Web References: +

- History of RAF Organisation: http://www.rafweb.org

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

If you love our website please donate so we can make this site even better !!

-ready-to-land-Feb-1944-80-G-269036.jpg)

-ready-to-land-Feb-1944-ASC.jpg)

-in-the-North-Atlantic-12th-April-1944-80-G-269035.jpg)

-in-the-North-Atlantic-12th-April-1944-ASC.jpg)