Photographic Information

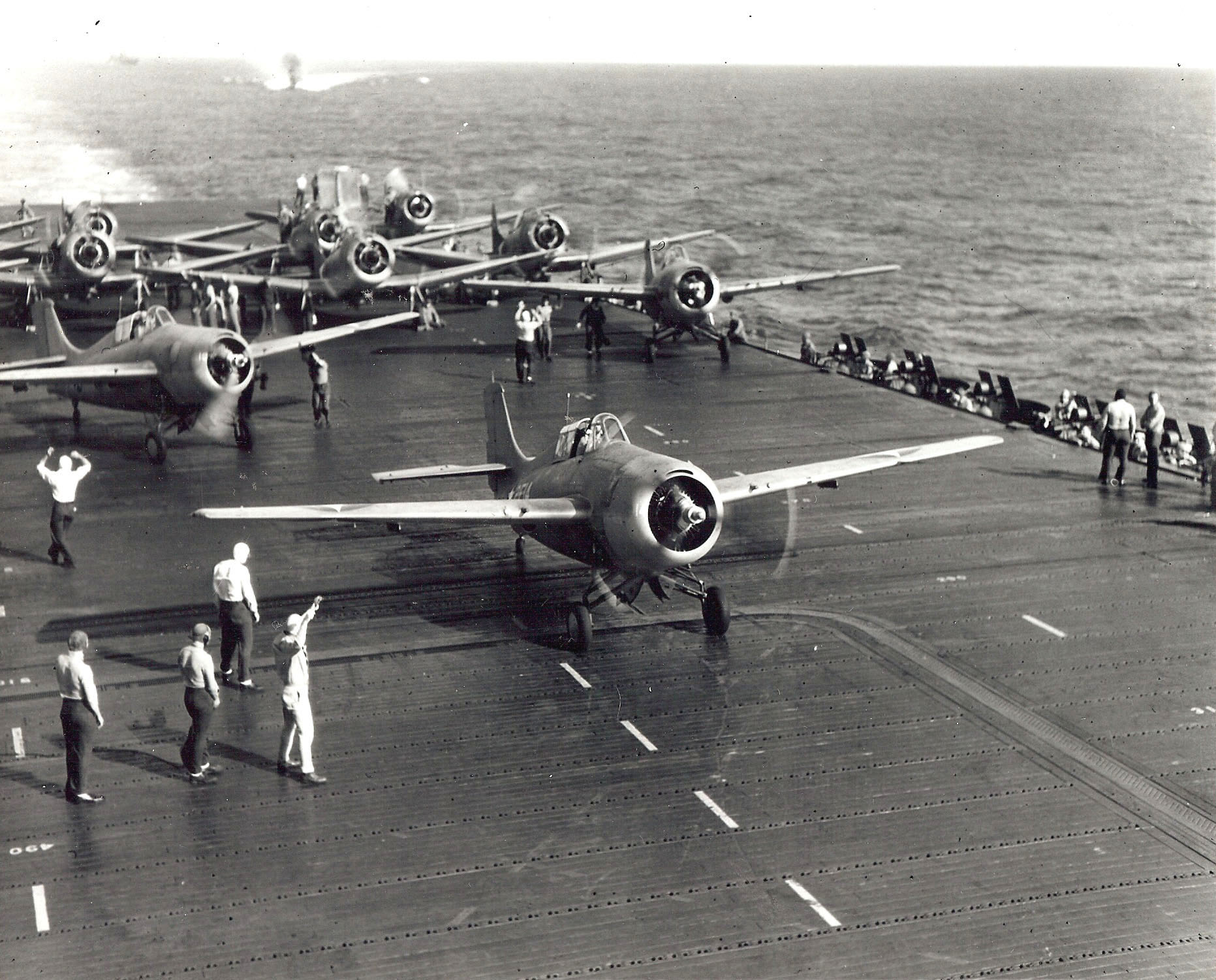

USN Fighter Squadron Two VF-2 colorized slideshow

Asisbiz colorized photo gallery and history of USS Ranger CV-4

The Pilot was USMC Lt. E.H. 'Butch' O'Hare.

Lieutenant Edward Henry ('Butch') O'Hare, USN

Seated in the cockpit of his Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter, circa spring 1942.

The plane is marked with five Japanese flags, representing the five enemy bombers he was credited with shooting down as they attempted to attack USS Lexington (CV-2) northeast of the Solomon Islands on 20 February 1942.

The censor has blanked out the Fighting Squadron Three 'Felix the Cat' insignia below the windshield.Photograph from the Office of War Information collection in the U.S. National Archives.

Loss of Medal of Honor Recipient Lieutenant Commander Butch O’Hare

After sundown on 26 November 1943, the U.S. Navy attempted the first carrier-based night fighter intercept operations. The fighters were launched in response to continuing night attacks by Japanese land-based twin-engine Betty torpedo bombers (which had previously hit and damaged the light carrier Independence. During the mission, the commander of Enterprise Air Group, Lieutenant Commander Edward H. “Butch” O’Hare, was shot down, and neither his aircraft or body were ever found. O’Hare had previously been awarded the Medal of Honor for single-handedly downing several Japanese Betty torpedo bombers attempting to strike the aircraft carrier Lexington (CV-2) on 20 February 1942, making him the first naval aviator to be awarded the Medal of Honor in World War II. This also made him an instant national hero at a time when the nation needed one in the dark days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Like the loss of Doris Miller on Liscome Bay, the loss of Butch O’Hare was a shock to the American public. For many years, there was uncertainty as to whether he was shot down in the darkness by “friendly fire” from another Navy aircraft or whether he was shot down by the Japanese. The analysis that I find most compelling indicates that he was hit and downed by a lucky shot from one of the Betty bombers.

O’Hare came from a colorful background. At the time O’Hare was seeking to enter the U.S. Naval Academy, his father was a lawyer working for mobster Al Capone, but who turned on Capone providing key evidence leading to the gangster’s conviction on tax evasion, and was rewarded for his efforts by being gunned down in a mob hit in November 1939. Despite this, O’Hare graduated from the Naval Academy in 1937 and finished aviation training in May 1940, reporting to Fighter Squadron 3 (VF-3), where future “ace” Lieutenant John S. “Jimmy” Thach was executive officer. Thach quickly recognized O’Hare’s talent, especially at gunnery. When Saratoga (CV-3) was torpedoed and damaged by a Japanese submarine on 11 January 1942, VF-3 transferred to Lexington, replacing her obsolete F2A Brewster Buffalo squadron, and was re-designated VF-2. Thach led one section and future ace (and four-star) Noel Gayler led the other.

On 20 February 1942, Task Force 11, centered on Lexington, was approaching the Japanese base of Rabaul (which had yet to develop the formidable air defenses seen in 1943), but was detected by a Japanese flying boat while still 450 miles away. At 1112, Thach and another pilot shot down the four- engine Kawanishi H6K4 Type 97 Mavis at 43 nautical miles from the carrier, but not before the plane had radioed a report. At 1202, two other Lexington fighters shot down a second Mavis, while a third radar contact turned away. The Japanese wasted no time in launching a two-group 17-plane strikeof G4M Betty medium torpedo bombers. Unfortunately for the Japanese, no torpedoes or fighters had arrived at Rabaul yet, so the Bettys carried only bombs, and launched with no fighter escort.

At 1542, Lexington radar detected the incoming strike at long range, but lost the contact. At 1625, radar re-acquired the incoming strike at 47 nautical miles and closing fast, which turned out to be nine Bettys. Fighters were vectored to intercept and additional fighters were launched, including O’Hare (flying F4F BuNo. 4031 “White 15”), but O’Hare and his wingman Marion “Duff” Dufilho were held overhead as the Bettys were engaged and five were shot down. Four of the Betty’s dropped bombs on Lexington, but missed by 3,000 yards. The surviving Bettys were pursued and shot down, although two Wildcats were shot down by the Bettys’ lethal tail guns. One of the Bettys was actually shot down by an SBD Dauntless dive bomber on ASW patrol.

However, at 1649, Lexington radar detected a second formation of Bettys approaching from the disengaged side at a range of only 12 nautical miles. The situation was critical as seven Wildcats were pursuing the remnants of the other formation of Bettys in the opposite direction, while five were orbiting, waiting to recover and low on fuel. O’Hare and Dufilho were vectored toward the new threat and intercepted the incoming Bettys (reported as nine, but actually eight) at 9 nautical miles from the carrier. Dufilho’s guns jammed and O’Hare attacked alone. (Early models of the Wildcat mounted four .50-caliber machine guns with 450 rounds per gun, which amounted to about 34 seconds of firing time.)

On his first firing pass, using a deflection technique he had developed (which kept him out of the envelope of the 20-mm cannon in the Betty’s tail position), O’Hare hit the two trailing Bettys, knocking them out of formation, one of them on fire. However, the crew of the burning Betty was able to extinguish the fire, and, unbeknownst to O’Hare, both Bettys were able to catch up and rejoin the formation before the weapons release point. On his second firing pass, O’Hare hit two Bettys in a trailing “V” formation, one of which crashed in flames while the other dumped its bombs and aborted.

As the Betty’s approached their bomb release point, O’Hare made his third firing pass, shooting down the leader of the trailing “V,” and then shooting down the plane of the Japanese mission commander, Lieutenant Commander Takuzo Ito. O’Hare made a fourth firing pass on what was actually one of the planes that had caught up, but ran out of ammunition. As Ito’s command plane was falling, his command pilot, Warrant Officer Chuzo Watanabe, attempted to crash the flaming plane into Lexington, but missed. The four surviving Bettys dropped ten 250-kilogram bombs on Lexington, but missed, this time by only 100 feet. Of the 17 Betty bombers, only two made it back to Rabaul, both damaged by O’Hare.

O’Hare claimed to have shot down six Bettys and damaged one. Lexington’s commanding officer, Captain Frederick “Ted” Sherman, reduced it to five, since four of what was believed at the time to be nine aircraft flew over the Lexington. Lieutenant Commander Thach reported seeing three planes falling in flames at the same time, which, based on post-war records, was in fact the actual number, as only eight Japanese planes were in the second strike. Nevertheless, O’Hare was given credit for five kills, which made him the first Navy ace of the war. O’Hare’s plane received only one bullet hole in the engagement, although he was fired on by a Lexington .50-caliber gunner while returning, who fortunately didn’t lead enough. O’Hare’s historic aircraft crashed while later being transferred to Yorktown (CV-5). O’Hare was sent back to the States and, on 21 April 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt presented him with the Medal of Honor:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in aerial combat, at grave risk to his life above and beyond the call of duty, as section leader and pilot of Fighting Squadron 3 on February 20, 1942. Having lost the assistance of his teammates, Lieutenant O’Hare interposed his fighter between his ship and an advancing enemy formation of 9 attacking twin-engine heavy bombers. Without hesitation, alone an unaided, he repeatedly attacked this enemy formation of 9 attacking twin-engine heavy bombers, at close range in the face of intense combined machine gun and canon fire. Despite this concentrated opposition, Lieutenant O’Hare, by his gallant and courageous action, his extremely skillful marksmanship in making the most of every shot of his limited amount of ammunition, shot down 5 enemy bombers and severely damaged a sixth before they reached the bomb release point. As a result of his gallant action – one of the most daring, if not the most daring action in the history of combat aviation – he undoubtedly saved his carrier from serious damage.”

After several months of duty as a national hero (and missing the Battle of the Coral Sea), Lieutenant Commander O’Hare assumed command of VF-3 from Thach on 19 June 1942 and spent the next year training others. On 15 July 1943, VF-3 swapped squadron designations with VF-6 and was equipped with the new F6F-3 Hellcat fighter. VF-6 was planned to go aboard Enterprise (CV-6), which is why the designation was changed, during a time when air group and squadron numbers were supposed to match the parent carrier’s hull number, a system that was soon given up on as too complicated. Instead, two thirds of O’Hare’s VF-6 (24 Hellcats) embarked on light carrier Independence (CVL-22) on 22 August 1943. It participated in the strikes on Marcus Island on 1 September 1942, the first combat missions for the Hellcat, during which O’Hare would be awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC.) He would be awarded a second DFC for actions on the Wake Island strikes on 5 October 1943.

On 17 September 1943, O’Hare became commander of Carrier Air Group 6 (CAG 6) embarked on Enterprise. However, his squadron, VF-6, was split up amongst the light carriers and VF-2 embarked on Enterprise instead. By this time of the war, it had become standard practice for the CAG to fly in a TBF Avenger configured as a command aircraft to coordinate strikes. However, O’Hare successfully lobbied to continue flying the F6F Hellcat.

During Operation Galvanic, groups of Japanese twin-engine Betty bombers, trained in making night torpedo attacks, flew from airfields in the Marshalls attempting to strike U.S. ships. On the evening of 25 November, 13 Betty twin-engine torpedo bombers from the Marshalls attacked the U.S. Northern Assault Group. However, Rear Admiral Turner’s insistence on constant battle drills while en route to Makin and Tarawa paid off. Due to radical (but purposeful) and constant maneuvering by the U.S. ships, the Japanese bombers were never able to gain an advantageous torpedo attack position. Nevertheless, the night-time raids represented a serious threat. In an attempt to counter these raids, the commander of the Northern Carrier Group (TG 50.2), Rear Admiral Arthur W. Radford (embarked on Enterprise), O’Hare, and the Enterprise air officer, Commander Tom Hamilton, worked to develop ad hoc tactics for conducting night carrier-based fighter intercepts.

The tactics involved using a “Bat Team” of one radar-equipped TBF Avenger and two F6F Hellcats. The Hellcats would join on the Avenger and would be vectored to the targets by the Enterprise fighter director officer based on shipboard radar, and then the Avenger would use its radar to lead the Hellcats to the incoming Japanese strike. Once the Hellcats sighted the blue-flamed exhaust of the Japanese bombers, they would engage. Four Bat Team fighter pilots were selected, one of which was Lieutenant Roy Marlin Voris, who would later found and command the Blue Angels Navy Flight Demonstration Team.

On the night of 26 November 1943, another Japanese raid was detected inbound and the Bat Team was launched, with O’Hare choosing to fly one of the fighters himself. The other was flown by Ensign Warren Andrew “Andy” Skon of VF-2. The TBF-1C Avenger was flown by the VT-6 (“Black Panthers”) squadron skipper, Lieutenant Commander John C. Phillips. The night tactics proved harder to execute in practice than in theory. The fighter director had difficulty sending the Bat Team in the right direction, and the fighters had a hard time finding the TBF. When they did, it appears they were already in the middle of the Japanese formation flying the same direction.

O’Hare’s plane was last seen by his wingman and the TBF turret gunner at the five o’clock position on the TBF. The turret gunner then saw a Betty bomber that was above and behind O’Hare in the six o’clock position. The turret gunner fired on the Betty and the nose gunner in the Betty returned fire. O’Hare’s plane did not appear to have been hit in the crossfire, but both the turret gunner and wingman reported that O’Hare’s plane veered to the left, dropped down into the darkness, and was never seen again, suggesting that a round from the Betty’s nose gun killed or incapacitated O’Hare and he lost control of the aircraft. The action caused confusion in the Bettys’ formation and they broke off the attack. Navy historian Samuel Eliot Morison recorded that one Betty was shot down by Phillips in the TBF (which had a forward-firing gun). An extensive search for O’Hare failed to find any trace of him or his aircraft, and, on 9 December, he was officially declared missing in action. O’Hare would be awarded a posthumous Navy Cross for his last action:

“The President of the United States takes pride in presenting the Navy Cross (Posthumously) to Lieutenant Commander Edward Henry “Butch O’Hare, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism in operations against the enemy while serving as a Pilot of a carrier-based Navy Fighter Plane in Fighting Squadron TWO (VF-2), attached to the USS ENTERPRISE (CV-6), and deployed over Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands, in action against enemy Japanese forces on 26 November 1943. When warnings were received of the approach of a large force of Japanese torpedo bombers, Lieutenant Commander O’Hare volunteered to lead a fighter section of aircraft from his carrier, the first time such a mission had been attempted at night, in order to intercept the attackers. He fearlessly led his three-plane group in combat against a large formation of hostile aircraft and assisted in shooting down two Japanese planes and dispersed the remainder. Lieutenant Commander O’Hare’s outstanding courage, daring airmanship and devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest tradition of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.”

The Gearing-class destroyer, USS O’Hare (DD-889), launched 22 June 1945 was named in honor of Butch O’Hare and served until she was decommissioned in October 1973 and transferred to the Spanish Navy before being scrapped in 1992. On 19 September 1949, Chicago’s Orchard Depot Airport (ORD) was renamed Chicago O’Hare, and an F4F Wildcat, recovered from Lake Michigan in the 1990s and restored and on loan from the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, is on display in Terminal 2, painted in the markings of O’Hare’s Medal of Honor flight.

(Sources for this section include: “Defending the USS Lexington: Action off Bougainville” by Allyn Vannoy, 27 November 2018, on warfarehistorynetwork.com, and Fateful Rendezvous: The Life of Butch O’Hare by Steve Ewing and John B. Lundstrom, 1997.)

Bibliography:

Magazine References: +

- Airfix Magazines (English) - http://www.airfix.com/

- Avions (French) - http://www.aerostories.org/~aerobiblio/rubrique10.html

- FlyPast (English) - http://www.flypast.com/

- Flugzeug Publikations GmbH (German) - http://vdmedien.com/flugzeug-publikations-gmbh-hersteller_verlag-vdm-heinz-nickel-33.html

- Flugzeug Classic (German) - http://www.flugzeugclassic.de/

- Klassiker (German) - http://shop.flugrevue.de/abo/klassiker-der-luftfahrt

- Le Fana de L'Aviation (French) - http://boutique.editions-lariviere.fr/site/abonnement-le-fana-de-l-aviation-626-4-6.html

- Le Fana de L'Aviation (French) - http://www.pdfmagazines.org/tags/Le+Fana+De+L+Aviation/

- Osprey (English) - http://www.ospreypublishing.com/

- Revi Magazines (Czech) - http://www.revi.cz/

Web References: +

- History of RAF Organisation: http://www.rafweb.org

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

If you love our website please donate so we can make this site even better !!