Mitsubishi A6M Zero and its involvement in China during the Second Sino-Japanese War

7th July 1937 – 2nd Sept 1945Location: China, Vietnam, Mainland China

Introduction

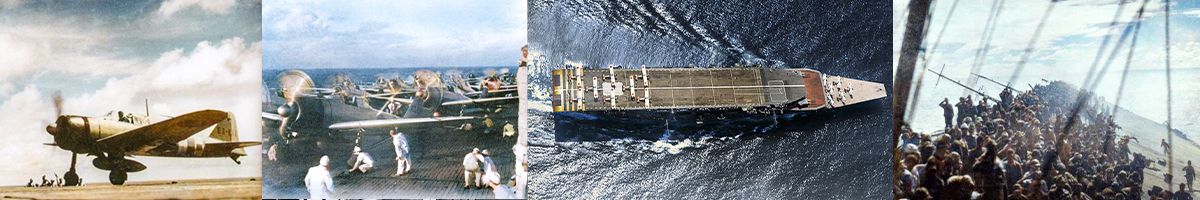

The Mitsubishi A6M Zero, officially known as the A6M Reisen (Zero-sen, or Type 0 Fighter) by the Japanese Navy, was one of the most iconic and effective fighter aircraft of World War II. Developed in the late 1930s, it became known to the Allies as the "Zero" due to its designation. Its primary involvement in the Chinese theater during WWII provides a significant lens through which to examine Japan's military strategy and the impact of air warfare in this region.

Design and Development

Background: The Zero was designed to meet the Japanese Naval Air Force's requirement for a carrier-based fighter with exceptional range, agility, and climbing ability. Designed by Jiro Horikoshi, it first flew in 1939.

Brief Specifications:

Engine: Nakajima Sakae 12 radial engine, providing a balance of performance and range.

Armament: Typically equipped with two 7.7 mm machine guns and two 20 mm cannons, which was formidable for its time.

Performance: Remarkable for its speed (over 300 mph), range (up to 1,930 miles with drop tanks), and maneuverability, though it lacked armor and self-sealing fuel tanks, making it vulnerable to enemy fire.Involvement in China

Initial Deployment: The Zero was first used in combat in China in 1940, shortly after its introduction. Its debut significantly shifted the aerial balance in favor of the Japanese forces due to its superior performance compared to Chinese and Soviet aircraft.

Strategic Impact:

Air Superiority: The Zero's initial success in China was due to its ability to outmaneuver and outclimb most contemporary fighters. This allowed Japan to control the skies, supporting ground operations and bombing raids on strategic targets.

Tactics: The Japanese pilots employed the Zero's strengths in hit-and-run tactics and ambushes, which were particularly effective against less agile opponents.

Key Battles:

Chongqing Bombings: During the extensive bombing campaigns on Chongqing (Chungking), Zeros provided escort for bombers, protecting them from Chinese fighters. The city was bombed repeatedly from 1938 to 1943, with Zeros ensuring air superiority.

Burma Campaign: Though primarily in China, Zeros also supported operations in Burma, which had strategic implications for China's supply lines.

Evolution Over Time: As the war progressed, the Zero's design was incrementally improved (A6M2 to A6M5 variants), but Allied technology and tactics caught up. The Zero began to face stiffer competition from newer Allied fighters like the P-51 Mustang and F4U Corsair, leading to higher losses.

Battle details of the Mitsubishi A6M Zero in China

1. Battle of Chongqing (Chungking)

The Battle of Chongqing, often remembered as the Chongqing Bombing, was one of the most harrowing and prolonged aerial campaigns of the Second Sino-Japanese War, spanning from 1938 to 1943. Chongqing, a mountainous city in southwestern China, became the wartime capital of the Nationalist government after the fall of Nanjing in 1937. This relocation made it not just a political center but a symbol of Chinese resistance, and thus, a prime target for the Japanese forces seeking to crush Chinese morale and force a surrender.

The campaign began in earnest in 1938, as Japan, having secured much of eastern China, turned its attention to breaking the will of the Chinese leadership. Chongqing's strategic importance was clear, but its geography posed challenges. Nestled among steep hills and bordered by the Yangtze and Jialing Rivers, the city was difficult to attack by land, making air raids the preferred method of assault. The Japanese aimed to terrorize the civilian population, disrupt government operations, and destroy military infrastructure through relentless bombing.

The initial phase of the bombings was marked by daylight raids, with Japanese aircraft, including bombers like the Mitsubishi G3M and G4M, escorted by the newly introduced Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters, flying from bases in occupied territories. These raids were devastating, targeting not just military installations but also residential areas, schools, and hospitals. The city's civilian population bore the brunt of the attacks, with thousands killed in the early strikes. The Japanese pilots, confident in their air superiority, flew in tight formations, their Zeros outmaneuvering the Chinese Air Force's outdated Soviet-supplied fighters like the Polikarpov I-15 and I-16.

As the campaign intensified in 1939 and 1940, the bombings became more frequent and brutal. The Japanese shifted tactics, incorporating night raids to maximize terror and minimize losses from Chinese anti-aircraft fire. The city's defenses, initially weak, struggled to respond. Chongqing's air raid shelters, dug into the hillsides, became a lifeline for the population, but many were inadequate against the high-explosive bombs and incendiaries dropped by the Japanese. Fires swept through the city, fueled by its wooden structures, leaving vast swathes in ruins.

The Chinese response evolved over time, driven by necessity and desperation. The Nationalist government, under Chiang Kai-shek, called for national unity and resilience, urging citizens to endure. The Chinese Air Force, bolstered by Soviet aid and later by the American Volunteer Group (Flying Tigers), began to challenge Japanese air superiority. Anti-aircraft batteries were improved, and barrage balloons were deployed to disrupt low-flying bombers. Despite these efforts, the Japanese maintained the upper hand, their Zeros proving formidable in dogfights, often diving from high altitudes to strike and then retreating before Chinese pilots could effectively counter.

The human cost was staggering. Estimates suggest that over 10,000 civilians were killed, with tens of thousands injured and countless more displaced. The bombings aimed not just at destruction but at psychological warfare, with leaflets dropped to demoralize the population and encourage surrender. Yet, the people of Chongqing showed remarkable resilience, rebuilding after each raid and continuing to support the war effort. The city's endurance became a symbol of Chinese defiance, rallying support both domestically and internationally.

By 1941, the campaign began to wane, not because of a lack of Japanese intent but due to shifting priorities. The attack on Pearl Harbor and the expansion of the war in the Pacific stretched Japanese resources thin. The bombings continued sporadically until 1943, but their intensity decreased. The Chinese, meanwhile, had adapted, with better air defenses and increased Allied support, including the arrival of American aircraft and pilots, which helped level the playing field.

The fall of Chongqing never came, but the scars of the campaign remained. The city emerged from the war battered but unbroken, its survival a testament to the spirit of its people. The bombings had profound effects on Chinese strategy, highlighting the need for stronger air defenses and international alliances. For Japan, the campaign was a mixed success; while it inflicted significant damage, it failed to break Chinese resistance, and the resources expended weakened their broader war effort.

The story of Chongqing is one of terror, endurance, and the harsh realities of aerial warfare. It's a tale of how a city, thrust into the heart of a global conflict, became a crucible of resistance, its people enduring unimaginable hardship to hold the line against an unrelenting enemy.

Duration: From 1938 to 1943, with the most intense bombing occurring between 1939 and 1941.

Role of the Zero: Escort Mission: Zeros were used to escort Mitsubishi G3M and G4M bombers, providing protection from Chinese fighter planes. Their long range was crucial for these deep penetration missions into Chinese territory.

Air Superiority: The agility and climbing ability of the Zero allowed it to engage and often outmaneuver the Chinese Air Force's Curtiss Hawk 75s, I-15s, and I-16s. This air cover was essential, reducing bomber losses significantly.

Tactics: Japanese pilots would often use the Zero's superior performance to perform high-altitude dives, catching Chinese fighters off-guard or retreating quickly if outnumbered.2. Battle of Hankou (Hankow)

The Battle of Hankou, often referred to as the Battle of Wuhan, was one of the most significant engagements of the Second Sino-Japanese War, taking place in the late summer and autumn of 1938. Hankou, part of the tri-city area of Wuhan, was not just a major city but the political and economic heart of central China, making it a strategic target for the Japanese forces aiming to break Chinese resistance.

As Japan's campaign pushed further into China, following their capture of Nanjing, their eyes turned to the Yangtze River valley. Wuhan, with its confluence of the Yangtze and Han Rivers, was crucial for both military and symbolic reasons. The Chinese Nationalist government, led by Chiang Kai-shek, had moved significant administrative functions to Wuhan, making it a symbol of Chinese resistance.

The battle commenced in earnest in June of 1938, with the Japanese initiating a multi-pronged attack aimed at encircling Wuhan. Their strategy involved capturing key towns and cities along the river to cut off supplies and reinforcements to the Chinese defenders. The Japanese forces were methodical, using their navy to control the Yangtze, while their air force, including the newly introduced Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters, sought to gain air superiority.

The city of Hankou was a fortress of sorts, with the Chinese having prepared defenses over months. They had constructed fortifications, mobilized troops from across China, and set up anti-aircraft defenses. The Chinese forces numbered around 800,000, a testament to the importance they placed on defending Wuhan. However, they were often underequipped and lacked the modern weaponry that the Japanese possessed.

One of the most intense aspects of the battle was the aerial combat over Hankou. Japanese Zero fighters showcased their agility and firepower against the less advanced Chinese aircraft, which included Soviet-supplied fighters like the Polikarpov I-15 and I-16. The battles in the sky were fierce, with both sides suffering losses, but the Japanese airmen, with their superior training and aircraft, generally held the upper hand.

On the ground, the fighting was brutal. The Japanese used their advantage in artillery to bombard Chinese positions, while infantry engagements in the city led to street-by-street fighting. The Chinese employed guerrilla tactics alongside conventional warfare, making the most of the urban landscape and the natural barriers provided by the rivers.

The battle stretched into October, with the Japanese tightening their noose around Wuhan. They captured strategic points like Jiujiang and Huangmei, cutting off supply routes. The Chinese, realizing the untenable situation, executed a strategic withdrawal. Chiang Kai-shek decided to preserve his forces rather than fight to the last man, moving his government further inland to Chongqing.

The fall of Hankou on October 26, 1938, was a significant blow to Chinese morale but also demonstrated the resilience and determination of Chinese forces. The battle had lasted for months, far longer than the Japanese had anticipated, leading to high casualties on both sides. The Japanese victory was pyrrhic; they suffered around 140,000 casualties, while the Chinese losses were even higher, with estimates around 400,000.

The long battle of Hankou also had profound effects on Japanese strategy. It drained their resources and exposed vulnerabilities in their military capabilities, particularly in terms of logistics and sustaining such an extended campaign far from home. For China, the retreat from Wuhan was not a defeat but a strategic maneuver that allowed them to regroup and continue the fight from a new base.

The story of Hankou is one of sacrifice, strategy, and the harsh realities of war. It's a tale of how air power, naval strategy, and ground combat intertwined in one of the largest urban battles of the era, leaving an indelible mark on the history of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Time Frame: Part of the larger Wuhan Campaign in 1938.

Zero's Contribution: Control of Airspace: Zeros helped secure air superiority over the city, which was a major transport hub on the Yangtze River. This was vital for Japanese ground forces as they moved to encircle and capture Wuhan.

Dogfights: Here, Zeros proved their worth in dogfights against Soviet-supplied aircraft, demonstrating their maneuverability and rate of climb.3. Operations Along the Burma Road

The Burma Road was not just a supply line but a lifeline for China during World War II, connecting the port of Rangoon in British Burma (now Myanmar) to Kunming in China's Yunnan province. This 717-mile road was crucial for transporting war materials to China's Nationalist forces led by Chiang Kai-shek, who were battling Japanese invaders. The operations along the Burma Road were multifaceted, involving military engagements, logistical challenges, and strategic maneuvers that shaped the course of the war in Asia.

The road's significance escalated after Japan's invasion of China in 1937, which led to the blockade of China's eastern ports. As the only viable overland route for supplies, the Burma Road became a focal point of both Japanese strategy to cut off Chinese support and Allied efforts to keep China in the war.

In 1940, under diplomatic pressure from Japan, Britain agreed to close the Burma Road temporarily, but it was reopened in 1941 due to international pressure and the worsening situation in China. When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, simultaneously invading Southeast Asia, including Burma, the road's strategic importance intensified.

Japanese Operations:

The Japanese campaign to capture Burma began in earnest in January 1942. Their aim was twofold: to sever the supply line to China and secure Burma as a base for potential attacks on India. The Japanese forces, moving through Thailand, rapidly advanced into Burma, capturing Rangoon in early March 1942, effectively cutting off the Burma Road at its source. The Japanese air force, with the Mitsubishi A6M Zero providing air cover, played a significant role in these operations. Zeros escorted bombers targeting supply convoys, strafing vehicles, and engaging Allied aircraft that tried to protect or resupply the road.

Allied Countermeasures and Operations:

The fall of Rangoon forced the Allies to rely on air supply routes, known as "The Hump," flying over the Himalayas from India to China. This was a dangerous and costly operation, with many planes lost to the harsh conditions and Japanese fighters. However, the Allies did not abandon the idea of re-establishing a land supply route.

General Joseph Stilwell, an American officer in charge of the China-Burma-India theater, was instrumental in planning operations to reopen the road. His strategy involved training Chinese troops in India and launching offensives to recapture northern Burma. The operations in this region included:

The Ledo Road: Also known as the Stilwell Road, this was an Allied construction project aimed at reconnecting India and China overland. It started from Ledo in India, crossing into Burma and linking up with the original Burma Road at Mong Yu. Despite the massive engineering effort, this road was not completed until January 1945, by which time its strategic value had diminished due to the shifting focus of the war.

Chindit Operations: British Brigadier Orde Wingate led long-range penetration groups known as the Chindits, conducting raids behind Japanese lines to disrupt supply routes and communications, indirectly supporting the Burma Road operations by drawing Japanese forces away from key areas.

Battle of Myitkyina: A pivotal engagement where Allied forces, including American-trained Chinese troops, captured this vital Burmese town in August 1944. This battle was part of the broader effort to secure northern Burma and thus protect and eventually reopen the road.

Aerial Engagements: The Zero was frequently seen in the skies over Burma, both in offensive roles attacking convoys and in defensive actions against Allied air raids. However, by 1944, the Zero was increasingly outmatched by newer Allied fighters like the P-51 Mustang and P-47 Thunderbolt, reducing its dominance in aerial combat.

The Legacy:

The operations along the Burma Road highlighted the logistical and strategic challenges of WWII in Asia. The road symbolized the Allied commitment to keeping China in the fight against Japan but also demonstrated the lengths to which Japan would go to isolate and defeat China. The eventual reopening of the Burma Road through the Ledo Road came too late to significantly alter the war's outcome in China, but it did help in maintaining morale and supplying the Chinese forces until the war's end.

This narrative underscores the Burma Road's role not just as a physical pathway but as a critical artery in the broader context of the Asian theater, where geography, climate, and human endurance played as significant roles as military strategy.

Context: The Burma Road was crucial for China's supply line from the British colony of Burma.

Zero's Role: Interdiction Missions: Zeros were part of the air forces used to interdict supply routes, bombing and strafing convoys. They also engaged in dogfights with British and American aircraft trying to protect these supply lines.

Strategic Bombing: In support of ground operations, Zeros often escorted bombers targeting infrastructure along the road, aiming to cut off supplies to Chiang Kai-shek's forces.4. Battle of Changsha (1939, 1941, 1942)

The Battles of Changsha were a series of significant military engagements during the Second Sino-Japanese War, occurring in 1939, 1941, and 1942. Changsha, a key city in Hunan Province, was strategically vital due to its location on the Xiang River, serving as a transportation hub and a defensive line against Japanese advances towards the heartland of China. Here's an in-depth look at each battle:

1939 - First Battle of Changsha:

The first battle began in September 1939 when Japanese forces, fresh from their successes in the north and east, aimed to expand their control over central China. The Japanese strategy was to capture Changsha, which would open the way to the rich agricultural lands of Hunan and further disrupt Chinese supply lines.

Initial Japanese Advance: The Japanese 11th Army, under General Yasuji Okamura, moved south, employing a pincer movement to surround Changsha. They had a mix of infantry, artillery, and air support, including the Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters which provided air superiority and attacked Chinese positions and reinforcements.

Chinese Defense: The Chinese, led by General Xue Yue, had fortified Changsha, preparing extensive defensive positions and employing a tactic known as "Heavenly Trap," which involved luring the enemy deep into Chinese-held territory before encircling and destroying them.

Outcome: After several weeks of fierce fighting, the Chinese managed to launch a counteroffensive, catching the Japanese in an overextended position. The Japanese were forced to retreat in late October, suffering heavy losses. This was a significant morale booster for the Chinese and a rare clear victory against Japanese forces.

1941 - Second Battle of Changsha:

The second battle unfolded in September 1941, with the Japanese aiming to avenge their previous defeat and secure Changsha before their planned expansion into Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

Japanese Strategy: This time, the Japanese approached with more caution but still underestimated Chinese defensive preparations. They launched a three-pronged attack, aiming to overwhelm Chinese defenses through sheer numbers and coordinated assaults.

Chinese Counter: General Xue Yue employed a similar strategy to the first battle, using the terrain to his advantage. The Chinese had improved their defenses, including more effective use of artillery and fortifications.

Outcome: Once again, the Chinese managed to repel the Japanese, who were unable to break through the fortified lines. The Japanese withdrawal was even more humiliating than before, with significant losses in men and material, leading to a pause in major operations in the area.

1942 - Third Battle of Changsha:

The third battle in December 1942 was part of Japan's broader strategy to secure more territory in China, especially after their setbacks in other theaters like the Pacific.

Japanese Offensive: With lessons learned from previous failures, the Japanese launched a more methodical attack, with better coordination between air, land, and river forces. The Zero fighters were used extensively for reconnaissance and attack missions, trying to neutralize Chinese air defenses.

Chinese Resilience: Despite being war-weary, the Chinese defenses around Changsha were bolstered by new strategies and some Allied support. Chinese forces used the mountainous terrain and river systems to their advantage, launching ambushes and counterattacks.

Outcome: The battle was characterized by intense fighting, with both sides suffering significant casualties. However, the Chinese once again held Changsha, forcing another Japanese retreat. This battle was particularly costly for the Japanese, who were beginning to feel the strain of prolonged warfare on multiple fronts.

Common Threads:

Role of the Mitsubishi A6M Zero: In all three battles, Zeros were pivotal in providing air cover, reconnaissance, and engaging Chinese aircraft. Their performance was crucial for Japanese operations, though by 1942, they faced stiffer competition from American-supplied fighters like the P-40 Warhawk flown by the Flying Tigers.

Strategic Importance: Changsha's defense was not just about holding ground but symbolizing Chinese resolve. Each victory, despite the human cost, was a psychological blow to Japanese morale and a rallying point for Chinese resistance.

Human Cost: These battles were among the bloodiest of the conflict, with civilian populations also suffering greatly from the urban warfare and bombings.

Legacy: The Battles of Changsha are remembered in China as pivotal moments of resistance, demonstrating the complexity of warfare in an era where both sides had to adapt to new technologies and tactics. They also showed the limitations of Japanese imperial ambitions as the war dragged on.

This detailed narrative of the Changsha battles paints a picture of a theater where strategy, determination, and adaptation played out against the backdrop of a brutal conflict, shaping the course of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Repeated Engagements: Changsha saw several battles, with the Zero playing a pivotal role in each:

Air Support: Providing close air support to Japanese ground troops, Zeros would strafe Chinese positions, disrupt counterattacks, and provide reconnaissance.

Engagement with Newer Aircraft: By 1942, with more Allied aircraft in China, Zeros had to adapt to fighting against increasingly capable opponents like the P-40 Warhawk flown by the American Volunteer Group (Flying Tigers).5. Southern China Operations

The Southern China Operations during World War II encompassed a broad range of military engagements across the southern provinces of China, notably Guangdong, Guangxi, and parts of Fujian, between 1937 and 1945. These operations were part of Japan's broader strategy to control key coastal areas, secure supply lines, and extend their influence over Southeast Asia. Here's an exploration of these operations:

Initial Invasion and Early Campaigns:

1937-1938: The Japanese invasion of China began in earnest with the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in July 1937. Following the fall of Shanghai and Nanjing, Japanese forces moved southward, aiming to capture strategic ports like Guangzhou (Canton). The capture of Guangzhou in October 1938 was facilitated by naval operations and air superiority, where Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters played a significant role in supporting ground troops and attacking Chinese coastal defenses.

Guangdong and Guangxi: These provinces were critical due to their geographical significance, offering access to the South China Sea and proximity to Hong Kong, then a British colony. Japanese forces aimed to control these areas to disrupt supply routes to the Chinese interior and to use them as bases for further operations into Southeast Asia.

Key Engagements:

Battle of Nanning and Guilin: In late 1939 and throughout 1940, Japanese forces pushed into Guangxi, capturing Nanning and attempting to secure Guilin. These cities were vital for control over the region's transportation networks. The Zeros provided vital air support, engaging in dogfights with the Chinese Air Force, which was at this point, bolstered by Soviet-supplied aircraft.

Defense and Counterattacks: Chinese forces, led by figures like General Bai Chongxi, employed guerrilla tactics and leveraged the region's rugged terrain. They managed to slow down Japanese advances and even recapture some territories temporarily. The Zeros, while effective, faced increasing challenges from Chinese defenses adapting to their tactics.

Bombing Raids: Southern China saw frequent air raids, with Japanese bombers targeting military installations, transportation hubs, and industrial centers. Cities like Guangzhou were repeatedly bombed, causing significant civilian casualties and destruction. The Zero was instrumental in these operations, providing escort and engaging any aerial resistance.

The Role of Air Power:

Air Superiority: The Japanese maintained air superiority for much of the conflict in southern China, thanks to their superior aircraft, including the Zero. However, this dominance waned as the Chinese received more aid from the Allies, particularly from the United States, which introduced better aircraft and trained pilots.

Tactical Adaptations: The Japanese adapted their air tactics, focusing on hit-and-run raids to minimize losses, while the Chinese developed strategies to counter these, including the use of camouflage, dispersion of personnel, and the construction of underground bunkers.

Later Phases and Shifts:

1941-1944: After securing much of southern China, the Japanese shifted focus to consolidate control and counter Chinese guerrilla activities. The operations in this period were more about maintaining control than expanding territory. The Zero continued to play a role, though increasingly against Allied aircraft as U.S. involvement in the war grew.

Impact of U.S. Air Raids: By 1944, with the U.S. launching air raids from bases in China, the Japanese had to defend against attacks from both land and air, stretching their resources thin. The Zero, once a symbol of Japanese air dominance, began to encounter more formidable opposition.

Legacy:

Prolonged Conflict: The operations in Southern China illustrated the complexities of occupation and resistance in a vast and diverse region. The Japanese could control cities but never fully subdue the rural areas where resistance continued.

Strategic Relevance: These operations were part of Japan's Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere vision, aiming to secure resources and strategic positions. However, they also highlighted the overextension of Japanese military capabilities.

Human and Cultural Impact: The southern campaigns left lasting scars, with significant civilian casualties, displacement, and cultural loss. The resilience of the local population, alongside military resistance, became a part of the narrative of Chinese endurance during the war.

This narrative of the Southern China Operations provides a window into the strategic maneuvers, the suffering of the populace, and the shifting fortunes of war in one of the most fought-over regions during World War II.

Guangdong and Guangxi Provinces:

Raids and Patrols: Zeros conducted numerous raids and patrol missions to keep air superiority in these southern regions, facilitating Japanese control over strategic points like Canton (Guangzhou).

Defense Against Retaliation: They also defended against Chinese counterattacks, which became more frequent as the Chinese forces received better equipment from foreign allies.Tactical Shift Over Time

Adaptation: As the war continued, Zero pilots had to modify their tactics. The hit-and-run approach became less viable as Allied pilots learned to exploit the Zero's design flaws. Japanese pilots began to emphasize energy fighting rather than prolonged dogfights.

Losses: The Zero's effectiveness diminished as Allied air forces improved, but its role was never entirely diminished. The aircraft continued to serve in various capacities, including training and kamikaze missions towards the end of the war.

This detailed involvement in battles across China not only showcased the Zero's initial superiority but also highlighted the evolving nature of aerial combat during WWII. Remember, while these engagements happened in China, they were part of a broader Asian theater of war affecting multiple countries and regions.Decline and Legacy

Countermeasures: The Allies learned to exploit the Zero's weaknesses, particularly its lack of armor and self-sealing fuel tanks. Tactics like the "Thach Weave" were developed to counter the Zero's agility.

Production and Numbers: Despite these challenges, over 10,000 Zeros were produced, reflecting its key role in Japanese military aviation.

Post-War Legacy: The Zero became a symbol of Japanese air power in WWII. Its design influenced post-war aircraft, and several Zeros are preserved in museums around the world, including some in China, as reminders of the conflict.

Conclusion

The Mitsubishi A6M Zero significantly shaped the aerial dimension of Japan's campaign in China during World War II. Its initial superiority in the skies contributed to the effectiveness of Japanese strategies, though its vulnerabilities eventually led to a decline in its dominance. Understanding the Zero's role offers insights into the broader context of aerial warfare's evolution and the strategic use of technology in conflict.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto Japanese Aces by Full Name A6M Operators Japanese Aces by Surname Imperial Japanese Naval air units Japanese Aces by service and highest number of Kills

The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II

Bibliography:

- Bueschel, Richard M. Mitsubishi A6M1/2/-2N Zero-Sen in Imperial Japanese Naval Air Service. Canterbury, Kent, UK: Osprey Publications Ltd., 1970. ISBN 0-85045-018-7.

- Francillon, René J. The Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero-Sen (Aircraft in Profile number 129). Leatherhead, Surrey, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1966.

- Francillon, René J. The Mitsubishi A6M3 Zero-Sen ("Hamp") (Aircraft in Profile number 190). Leatherhead, Surrey, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1967.

- Green, William and Swanborough, Gordon. The Great Book of Fighters. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-7603-1194-3.

- Jackson, Robert. Combat Legend: Mitsubishi Zero. Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, UK: Airlife Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-84037-398-9.

- Juszczak, Artur. Mitsubishi A6M Zero. Tarnobrzeg, Poland/Redbourn, UK: Mushrom Model Publications, 2001. ISBN 83-7300-085-2.

- Marchand, Patrick and Takamori, Junko. (Illustrator) A6M Zero (Les Ailes de Gloire 2) (in French). Le Muy, France: Editions d’Along, 2000. ISBN 2-914403-02-X.

- Mikesh, Robert C. Warbird History: Zero, Combat & Development History of Japan's Legendary Mitsubishi A6M Zero Fighter. Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International, 1994. ISBN 0-87938-915-X.

- Mikesh, Robert C. and Watanabe, Rikyu. (Illustrator) Zero Fighter. London: Jane's Publishing Company Ltd., 1981. ISBN 0-7106-0037-2.

- Nohara, Shigeru. A6M Zero in Action(Aircraft #59). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, Inc., 1983. ISBN 0-89747-141-5.

- Nohara, Shigeru. Mitsubishi A6M Zero Fighter (Aero Detail 7) (in Japanese with English captions). Tokyo, Japan: Dai Nippon Kaiga Company Ltd., 1993. ISBN 4-499 22608-2.

- Okumiya, Masatake and Hiroikoski, Jiro (with Caidin, Martin). Zero! The Story of Japan's Air War in the Pacific: 1941-45. New York: Ballantine Books, 1956. No ISBN.

- Richards, M.C. and Smith Donald S. Mitsubishi A6M5 to A6M8 'Zero-Sen' ('Zeke 52')(Aircraft in Profile number 236). Windsor, Berkshire, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1972.

- Sakaida, Henry. Imperial Japanese Navy Aces, 1937–45. Botley, Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 1998. ISBN 1-85532-727-9.

- Sakaida, Henry. The Siege of Rabaul. St. Paul, Minnesota: Phalanx Publishing, 1996. ISBN 1-883809-09-6.

- Sheftall, M.G. Blossoms in the Wind: Human Legacies of the Kamikaze. New York: NAL Caliber, 2005. ISBN 0-451-21487-0.

- Willmott, H.P. Zero A6M. London: Bison Books, 1980. ISBN 0-89009-322-9.

- Wilson, Stewart. Zero, Hurricane & P-38, The Story of Three Classic Fighters of WW2 (Legends of the Air 4). Fyshwick, Australia: Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd., 1996. ISBN 1-875671-24-2.

Magazine References: +

- Airfix Magazines (English) - http://www.airfix.com/

- Avions (French) - http://www.aerostories.org/~aerobiblio/rubrique10.html

- FlyPast (English) - http://www.flypast.com/

- Flugzeug Publikations GmbH (German) - http://vdmedien.com/flugzeug-publikations-gmbh-hersteller_verlag-vdm-heinz-nickel-33.html

- Flugzeug Classic (German) - http://www.flugzeugclassic.de/

- Klassiker (German) - http://shop.flugrevue.de/abo/klassiker-der-luftfahrt

- Le Fana de L'Aviation (French) - http://boutique.editions-lariviere.fr/site/abonnement-le-fana-de-l-aviation-626-4-6.html

- Le Fana de L'Aviation (French) - http://www.pdfmagazines.org/tags/Le+Fana+De+L+Aviation/

- Osprey (English) - http://www.ospreypublishing.com/

- Revi Magazines (Czech) - http://www.revi.cz/

Web References: +

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_air_groups_of_the_Imperial_Japanese_Navy

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mitsubishi_A6M_Zero

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Japanese_Navy_Air_Service

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Mitsubishi_A6M_Zero_operators

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kamikaze

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tetsuz%C5%8D_Iwamoto

- http://mitsubishi_zero.tripod.com/

- http://ww2db.com/aircraft_spec.php?aircraft_model_id=3

- http://www.combinedfleet.com/ijna/a6m.htm

- http://www.combinedfleet.com/ijna/a6m-k.htm

- http://www.combinedfleet.com/ijna/a6m-n.htm

- http://www.j-aircraft.com/research/WarPrizes.htm

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

If you love our website please donate so we can make this site even better !!

-Heavy-Bomber-61st-Hiko-Sentai-9th-Hiko-Dan-over-Nomonhan-1939.jpg)