Dutch East Indies during World War II

Mitsubishi A6M Zero and its involvement in the Dutch East Indies during World War II

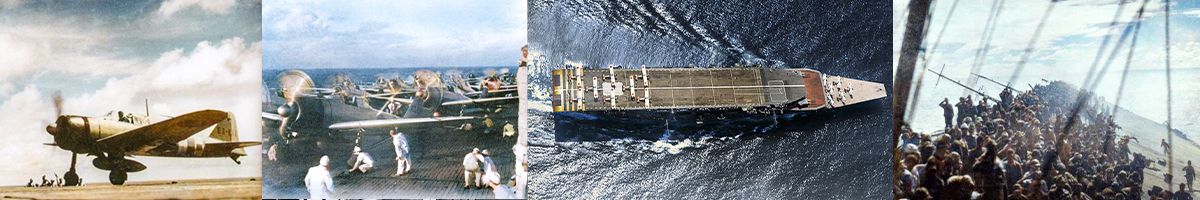

The Mitsubishi A6M Zero, also known as the "Zeke" to the Allies, played a significant role in the military campaigns across the Dutch East Indies during World War II.

Early Successes: The Zero was instrumental in the Japanese invasion of the Dutch East Indies. From December 1941 to March 1942, around 200 A6M2 Zeros were involved, achieving a high success rate against a variety of Allied aircraft. In this period, they reportedly downed 471 enemy aircraft out of 565 total enemy losses, showcasing their dominance in the early stages of the Pacific War. Aircraft Engaged: The Zeros faced off against a range of Allied fighters including the Brewster Model 339 Buffalo, Curtiss-Wright CW-21B Demon, Curtiss Hawk 75A-7, and Curtiss P-40 Warhawk. These Allied fighters were generally outmatched by the Zero in terms of maneuverability and range, leading to significant losses for the Dutch, British, American, and Australian forces.

Key Battles: Java Campaign: The Zero was central to air operations during the invasion of Java, where they protected Japanese bombers and naval forces, ensuring air superiority which was crucial for the successful Japanese landings. The Dutch capitulated on March 8, 1942, largely due to the overwhelming performance of the Zero in the skies.

Balikpapan and Avon Bases: The A6M2-N floatplane variant of the Zero was used to protect fueling depots in these locations, demonstrating its versatility by operating in both land and sea-based roles.

Tactics: Japanese pilots employed tactics leveraging the Zero's strengths, such as its long range and excellent maneuverability, to outflank and outmaneuver their opponents. The Zero's ability to operate at extended ranges allowed for surprise attacks and long-duration patrols, which were pivotal in the strategic envelopment of the Dutch East Indies.

Impact: The success of the Zero in these campaigns helped secure Japanese control over the resource-rich Dutch East Indies, which was vital for Japan's war efforts, providing them with oil, rubber, and other materials.

Later Operations: As the campaign moved towards New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, the Zero continued to dominate the initial engagements against Allied fighters like the P-40s and P-39s, further extending Japanese control over Southeast Asia.

The effectiveness of the Mitsubishi A6M Zero in these battles contributed significantly to the rapid fall of the Dutch East Indies to Japanese forces in early 1942, before the Allies could adapt their tactics and introduce more capable aircraft to counter the Zero's advantages.

Locations Involved in the Dutch East Indies Campaign

The locations involved in the battles featuring the Mitsubishi A6M Zero during the Japanese campaign in the Dutch East Indies include:

Tarakan: An island off the northeast coast of Borneo, known for its oil production.

Balikpapan: Also on Borneo, its oil refineries were crucial for both the Allies and the Japanese.

Makassar: A port city on the southwestern peninsula of Sulawesi, important for its air and naval facilities.

Palembang: On the island of Sumatra, this city was significant due to its oil refineries, one of the largest in Southeast Asia at the time.

Java Sea: Not a location per se, but the site of a major naval battle where Zeros provided air support, covering the waters around Java.

Bandung: An inland city in West Java, a key administrative and military center, targeted in the final push to control Java.

Surabaya: The second-largest city in Java and a major naval base, it was one of the last significant strongholds before the Dutch capitulation.Additional areas where Japanese forces, supported by Zero fighters, were active but might not have been directly involved in major battles include:

Ambon: An island where the Japanese made landings to secure airfields and disrupt Allied communications.

Kendari: On Sulawesi, where an airfield was captured to serve as a forward base for further operations.

Kupang: Located in the western part of Timor, where the Japanese aimed to isolate Australia from the Dutch East Indies.

Manado: In northern Sulawesi, taken early in the campaign to establish air superiority.These locations were all part of the broader strategy to capture resource-rich areas, secure strategic airfields, and isolate and conquer the Dutch East Indies, thereby cutting off Allied supply routes and bolstering Japan's war effort with vital resources.

Notable Aerial Battles during the Dutch East Indies Campaign

Battle of Tarakan (January 11-12, 1942)

Context: Tarakan was an important oil-producing island, making it a strategic target for Japan's resource acquisition.

Elaboration: Japanese forces conducted a two-pronged assault, with landings on both the north and south of the island. Zeros from the 21st and 23rd Air Flotillas, flying from nearby Borneo, provided continuous air cover and engaged in skirmishes with Dutch Brewster Buffalos and Martin B-10 bombers. The air superiority established by the Zeros was crucial in preventing Allied reinforcements and counterattacks, leading to the quick capture of the island.Battle of Balikpapan (January 23-24, 1942)

Context: Balikpapan was another significant oil center, with refineries and oil storage facilities that were vital for Japan's war machine.

Elaboration: The Tainan Air Group's Zeros were particularly effective here, not only defending the airspace but also conducting strafing runs on Allied positions and infrastructure. The Dutch, with limited air support, faced overwhelming odds. The Zeros' performance allowed Japanese ground forces to secure the area with minimal resistance. The destruction of oil facilities was a significant blow to Allied resources in the region.

Battle of Makassar (February 8-9, 1942)

Context: Makassar was a key port and airbase on Sulawesi, crucial for further operations in the region.

Elaboration: The 2nd Air Group's Zeros ensured that Japanese landings met with little aerial opposition. They engaged in dogfights with Dutch and Australian aircraft, including the Hawker Hurricane, which was outclassed by the Zero. The capture of Makassar allowed Japan to extend its air operations further south and east, tightening the noose around Java.

Battle of Palembang (February 13-15, 1942)

Context: Palembang on Sumatra was famous for its oil refineries, making it a prime target.

Elaboration: This operation included Japan’s first use of airborne troops, with Zeros from the 1st and 3rd Air Groups escorting paratroopers and then providing close air support. The air battle was intense, with Zeros engaging Brewsters and P-40s. The control of Palembang's oil was a significant strategic gain for Japan, though the refineries were heavily damaged.Battle of Java Sea (February 27, 1942)

Context: This was part of the broader strategy to isolate Java from external support.

Elaboration: While the primary combat was naval, Zeros from the 23rd Air Flotilla played a critical role in reconnaissance, bombing, and strafing Allied ships, as well as engaging any Allied aircraft that attempted to intervene. This contributed to the decisive Japanese victory, which led to the severing of Java's sea supply lines.Battle of Bandung (March 1, 1942)

Context: Bandung was a key city in the interior of Java, part of the final stages of the campaign.

Elaboration: As the Japanese moved inland, Zeros provided air support, bombing and strafing Dutch positions. They also intercepted and engaged Allied aircraft trying to support or evacuate from Java. The air cover was vital in the rapid advance of Japanese forces, leading to the encirclement and capitulation of Bandung.Battle of Surabaya (March 7-8, 1942)

Context: Surabaya was the last major stronghold in Java before the Dutch surrender.

Elaboration: Zeros from the Tainan and 3rd Air Groups dominated the skies, allowing Japanese ground troops to converge on the city. They engaged in numerous dogfights, securing air superiority. The continuous air attacks demoralized the defenders and paved the way for the final capitulation of Dutch forces in Java.These battles collectively showcased the Zero's pivotal role in the Japanese strategy, leveraging air superiority to support amphibious assaults, protect naval operations, and conduct effective ground support, ultimately leading to the fall of the Dutch East Indies.

Mitsubishi A6M Zero Post-March 1942

Japanese Consolidation and Defense (March 1942 - Late 1942)

Occupation and Air Patrols: After the conquest of Java, Zeros were used for patrolling and defending the newly acquired territories from Allied air raids. They were stationed across multiple airbases in Java, Sumatra, Borneo, and other islands to maintain air superiority.

Raids on Australia: Zeros escorted bombing raids on northern Australia, particularly targeting Darwin, aiming to disrupt Allied supply lines and bases.

Defensive Actions: Zeros engaged in defensive actions against Allied reconnaissance missions and bombing runs, intercepting and combating occasional raids on key installations.New Guinea and Solomon Islands Campaigns (Late 1942 - 1943)

Battle of the Coral Sea (May 4-8, 1942): Zeros from land-based units contributed to reconnaissance and sometimes engaged Allied aircraft during this carrier battle.

Defense of Rabaul: Zeros defended this major stronghold from Allied air attacks, engaging in numerous dogfights.

Guadalcanal Campaign: Zeros provided air cover for ground forces and engaged in aerial combat against increasingly sophisticated Allied aircraft.Air Superiority Challenges (1943 - 1945)

Battle of the Bismarck Sea (March 2-4, 1943): Zeros attempted to protect Japanese convoys but faced heavy losses.

New Guinea Campaign: Zeros were involved in maintaining air superiority as the Allies advanced, with diminishing success.

Philippines and Formosa (1944-1945): Participated in defense against massive US air raids, facing overwhelming American air power.

Kamikaze Operations: Towards the war's end, some Zeros were modified for kamikaze attacks.Final Days (1945)

Defense of the Home Islands: Zeros defended Japan from B-29 Superfortress raids, often in suicide missions or traditional dogfights.

Surrender: With Japan's surrender on August 15, 1945, the operational use of the Zero ended. Many were destroyed, while others were captured for evaluation by the Allies.These activities illustrate the Zero's transition from conquest to defense, facing increasingly challenging circumstances as the war progressed and Allied air power dominated.

Zero Units in the Dutch East Indies

Tainan Air Group (Kōkūtai)

The Tainan Air Group (台南海軍航空隊, Tainan Kaigun Kōkūtai) was a fighter aircraft and airbase garrison unit of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during the Pacific campaign of World War II. The flying portion of the unit was heavily involved in many of the major campaigns and battles of the first year of the war. The exploits of the unit were widely publicized in the Japanese media at the time, at least in part because the unit spawned more aces than any other fighter unit in the IJN. Several of the unit's aces were among the IJN's top scorers, and included Hiroyoshi Nishizawa, Saburō Sakai, Junichi Sasai, Watari Handa, Masaaki Shimakawa, and Toshio Ōta.

Bases: Taihoku (Taipei), Formosa (for initial operations), Balikpapan, Borneo, Denpasar, Bali, Surabaya, Java

Numbers: Approximately 40-50 Zeros during the initial campaigns.

Commander:

Capt. Higuchi Hiroshi (40) - 1 October 1941 - 4 October 1941

Cdr. / Capt. Saito Masahisa (47) - 4 October 1941 - 1 November 1942 (Promoted Captain on 1 May 1942.)

Captain Masahisa Saito - Commanded during early campaigns.

Lieutenant Saburō Sakai - A famous ace from this unit, based in Denpasar, Bali.Philippines and Dutch East Indies

The unit was formed at Tainan, Taiwan (then part of the Empire of Japan) on October 1, 1941 as part of the 23rd Air Flotilla. The unit's first commander was Captain Hiroshi Higuchi, who was relieved by Commander Masahisa Saito on 4 October 1941. Most of the unit's original pilots were veterans of aerial combat in the Second Sino-Japanese War. Just before the outbreak of war with the Allied powers, the unit consisted of 45 A6M Zero and 12 Type 96 fighter aircraft.

On 8 December 1941 forty-four Tainan aircraft escorted IJN bombers in attacks on US aircraft at Iba and Clark airfields on Luzon in the Philippines, a distance of 500 miles each way. The attacks almost completely destroyed General Douglas MacArthur's air forces. On 10 December Tainan Zeros shot down the B-17 bomber piloted by Colin Kelly. Later that month, the unit redeployed to the Philippines and continued to support Japanese forces as they overran and destroyed the territory's American and Filipino defenses.

The Tainan Naval Air Group then moved to Tarakan Island, followed by moves to Balikpapan and Denpasar, Bali to support the successful Japanese offensive into the Dutch East Indies beginning in January 1942. The unit's fighters helped inflict heavy losses on defending Allied aircraft in January and February 1942.

New Guinea

With the end of the campaign in March, the unit was integrated into the 25th Air Flotilla and redeployed to recently captured Rabaul, New Britain and Lae, Papua New Guinea in April. As of 25 April 1942, due to operational and combat losses, the Tainan Air Group, now under the command of Captain Masahisa Saitō, counted 26 Zero and six Type 96 "Claude" fighters.

The unit initially concentrated its aircraft at Lae to support an air campaign against the Australian and American forces stationed at Port Moresby. Between April and July, the Tainan Air Group flew 51 missions, totalling 602 sorties. During this time, the unit claimed to have destroyed 300 enemy aircraft. The Tainan's losses were 20 aircraft. Replacement aircraft gave the unit a total of 24 Zeros by August 1942, flown by 55 pilots. Because of the surplus in aircrew, only the most experienced pilots were allowed to fly combat missions.

Guadalcanal 1942

On August 7, United States Marines landed on Japanese-occupied Guadalcanal, initiating the Guadalcanal Campaign. In response that same day, 18 Tainan fighters escorted bombers from Rabaul for an attack on the Allied invasion fleet, the longest fighter mission of the war (556 miles each way) to that date. The Tainan claimed to have destroyed 43 enemy aircraft over Guadalcanal on that mission while losing two fighters with their pilots themselves. The Americans actually lost 10 aircraft, including nine of 18 fighters present, plus one dive bomber. The two Tainan pilots killed on this mission were Petty Officer First Class Yoshida and Petty Officer Second Class Nishiura

One significant Tainan casualty over Guadalcanal that day was Saburō Sakai, who was seriously injured and forced into a two-year recuperation. The US Marines on August 8 captured an airfield (later called Henderson Field) under construction by the Japanese on Guadalcanal which was soon operational with Allied aircraft.

Over the next several months, Tainan aircraft based at Rabaul engaged in repeated dogfights with Allied aircraft, called the Cactus Air Force, based on Guadalcanal. The extreme distances required for the Tainan pilots to fly from Rabaul to Guadalcanal severely hampered the unit's attempts to establish air superiority over the island. The unit also continued to support bombing missions against Port Moresby. Between August and November 1942, the Tainan lost 32 pilots killed in action. Junichi Sasai was killed on August 26 and Toshio Ōta on October 21.

On November 1, 1942 the Japanese naval units in the Southeast Pacific were reorganized. The Tainan was redesignated as the 251 Air Group and reconstituted with replacement aircrews. The 20 surviving pilots of the Tainan were transferred to Japan to help form new fighter units. Bergerud says only 10 pilots were left and that the new unit was not called the "251st Air Group". Each digit in "251" refers to a discrete attribute of the new organization.

3rd Air Group (Kōkūtai)

The 3rd Air Group (第三航空隊, Dai-san Kōkūtai) was a unit of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS) during the Pacific War that was involved in the Philippines campaign, Dutch East Indies campaign, air raids on Australia, and the Guadalcanal Campaign. The air group was redesignated as the 202nd Air Group on 1 November 1942.

Bases: Palembang, Sumatra, Bandung, Java, Kaohsiung, Kendari, Kupang, Rabaul

Numbers: Around 30-40 Zeros, though fluctuated with needs.

Commander:

Commander Yoshiro Hashiguchi - Known for leadership in various engagements.Southeast Asia

The group was formed on 10 April 1941 and was originally a medium bomber unit. However, in September it was reformed and became a fighter unit with an initial strength of 54 Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters and six Mitsubishi C5M reconnaissance aircraft. Prior to the outbreak of Pacific War, a small detachment was sent to operate over Malaya, while the majority of the group was stationed at Kaohsiung on Taiwan to participate in the invasion of Philippines. On 8 December, group's Hikōtaichō Lieutenant Yokoyama led the fighters to escort Mitsubishi G4M medium bombers from Takao Air Group and Kanoya Air Group in an attack against Iba Airfield. After the capture of Davao City, 3rd Air Group moved to an airfield there on 23 December and supported various landings around the area. As the Japanese forces advanced into the Dutch East Indies in 1942, the unit first moved to Menado, Celebes on 11 January, then to Kendari, Celebes on 25 January, and finally to Balikpapan, Borneo on 2 February. From there, Lieutenant Yokoyama led 27 Zero fighters to escort a major raid of 72 Mitsubishi G3M and G4M medium bombers against Surabaya and Denpasar, which cost the Allies around ten aircraft. Several smaller-scale attacks continued throughout February.

Australia 1942

After the end of the Dutch East Indies campaign, the group was stationed at Kupang on Timor and by March Lieutenant Yokoyama was replaced by Lieutenant Takahide Aioi as Hikōtaichō. From there the group started to conduct air raids on Australia. On 2 March, Buntaichō Lieutenant Zenjirō Miyano led nine Zero fighters in the Attack on Broome that destroyed seven enemy land aircraft and 15 flying boats. The first escort mission for medium bombers against Darwin occurred on 16 March, where Lieutenant (jg) Kawazoe Toshitada led only four Zero fighters. No air combat occurred as there were no enemy fighters stationed at Darwin at that time. This soon changed with the arrival of USAAF 9th Pursuit Squadron equipped with Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighters. On 30 March, Lieutenant Takeo Kurosawa led 12 Zero fighters to escort nine G4M medium bombers of Takao Air Group to Darwin. In the ensuing air combat with Warhawks, the Japanese suffered no losses and shot down one Warhawk. The next day a similar scenario occurred but no side suffered any losses. On 4 April, six G4M medium bombers of Takao Air Group and six Zero fighters from 3rd Air Group again attacked Darwin and were intercepted by seven Warhawks, which resulted in a loss of three bombers and two Warhawks. 9th Pursuit Squadron was reinforced by the other two squadrons from the 49th Pursuit Group and 3rd Air Group Zeros faced increased opposition. On 25 April, Lieutenant Aioi led 15 Zero fighters to escort 24 G4M medium bombers to Darwin and the engagement with Warhawks cost four bombers and one Zero fighter. Two days later, Lieutenant Kurosawa led 21 Zero fighters to escort 16 G4M medium bombers to Darwin. The raid was intercepted by 25 Warhawks and the 3rd Air Group managed to shoot down three of them for no loss. As the enemy started to raid Kupang airfield in return, 3rd Air Group (as well as Takao Air Group) moved further back to Kendari, and raids on Darwin were suspended until June in order for Takao Air Group to rebuild.

On 13 June, the raids against Darwin resumed and Lieutenant Aioi led a strong force of 45 Zero fighters to escort 27 G4M medium bombers. The raid was intercepted by Warhawks of the 49th Pursuit Group and the resulting air combat accounted for five Warhawks and two Zeros shot down. The next day 3rd Air Group's 27 Zero fighters under Lieutenant Tadatsune Tokaji performed a fighter sweep without Takao Air Group bombers, which resulted in one Warhawk shot down for no loss of Zeros. On 15 June, 27 G4M medium bombers of Takao Air Group and 21 Zero fighters from 3rd Air Group under Lieutenant Kurosawa again attacked Darwin and were intercepted by 28 Warhawks. The Zeros shot down two Warhawks while protecting the bombers and suffered no losses. The next day, Lieutenant Aioi led 27 Zero fighters to escort 27 G4M medium bombers. 18 Warhawks intercepted and the Zeros shot down three of them for no loss in return. No further attacks were conducted by the 3rd Air group until 30 July, when Lieutenant Aioi led 26 Zero fighters to escort 26 G4M medium bombers. The air combat over Darwin accounted for one Warhawk and one Zero. The final day-time raid on Darwin occurred on 23 August when 27 G4M medium bombers were escorted by 27 Zeros of the 3rd Air Group led by Lieutenant Tokaji. The intercepting 36 Warhawks managed to shoot down one bomber and four Zeros; Tokaji was one of the pilots killed in action. All further operations against Darwin were suspended until 1943.

Guadalcanal

As the fighting over Guadalcanal intensified, 23rd Air Flotilla loaned a portion of 3rd Air Group to 25th Air Flotilla at Rabaul. On 17 September, 21 Zero fighters and 27 pilots under the command of Lieutenant Aioi were ferried to Rabaul by the carrier Taiyō. Their first mission against Guadalcanal was flown on 27 September, when Lieutenant Aioi led 26 Zeros to escort 18 G4M medium bombers from Kisarazu and Takao Air Groups. They were intercepted by a large force of US Marine and US Navy Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters, which resulted in two bombers and one Zero shot down. On 29 September, Lieutenant Aioi led 27 Zeros in a fighter sweep over Guadalcanal, where they were engaged by 14 US Navy Wildcats. Only Zeros from Lieutenant Sadao Yamaguchi's division actually fought the Wildcats and managed to shoot down two for the loss of two zeros. Throughout October, smaller portions of 3rd Air Group would continue to fly missions against Guadalcanal in mixed teams with Tainan, 2nd and 751st Air Groups. The 3rd Air Group was redesignated as the 202nd Air Group on 1 November and was then withdrawn to Japan on 8 November. During the Guadalcanal campaign they lost eight aircraft and six pilots.

Australia 1943

At the beginning of 1943, the 202nd again began operations against Darwin in Australia. The first mission took place on 2 March, when Lieutenant Commander Aioi led 21 Zeros in a low-level approach and strafed the airfield, destroying one Bristol Beaufighter on the ground. Newly arrived Supermarine Spitfire fighters from RAAF No. 1 Wing scrambled and engaged the withdrawing Zeros, however, there were no losses. After the mission, Lieutenant Aioi was replaced as a Hikōtaichō. On 15 March, 16 G4M medium bombers of 753rd Air Group (ex-Takao) were escorted by 27 Zero fighters to attack Darwin. In the air combat over Darwin, the 202nd Air Group shot down four Spitfires for the loss of a single Zero. On 2 May, the group's new Hikōtaichō Lieutenant Commander Suzuki led 26 Zero fighters to escort 25 G4M medium bombers in another mission against Darwin. This time 202nd Air Group Zeros completely outmatched Spitfires by shooting down five of them, while another nine force-landed for various reasons. No losses of Zeros or bombers occurred on this occasion. On 10 and 28 May 202nd Air Group's Zero fighter attacked Milingimbi Island. On the former date, one Zero were lost for one Spitfire shot down, while on the latter they shot down two Spitfires for no loss, however, two escorted bomber were lost.

The attacks resumed one month later on 28 June, when nine medium bombers were escorted to Darwin by 27 Zeros under Lieutenant Commander Suzuki Suzuki. RAAF scrambled 42 Spitfires but neither side suffered any combat losses. A major raid targeting Fenton Airfield south of Darwin took place on 30 June, when Lieutenant Commander Suzuki led 27 Zero fighters to escort 23 G4M medium bombers. They were met by a large force of 39 intercepting Spitfires and four of them were shot down for no loss of Zeros or bombers. Another raid on Fenton was conducted on 6 July, where 26 escorting 202nd Air Group fighters met with 33 intercepting Spitfires. The engagement ended up with five Spitfires shot down for no loss of Zeros. While the medium bombers from 753rd Air Group ceased day-time raids against Darwin from that point on, 202nd Air Group 36 Zeros under Lieutenant Commander Suzuki escorted two reconnaissance aircraft over Northern Australia on 7 September. They were intercepted by 36 Spitfires and air combat accounted for one Zero and three Spitfires. During 1943, in the engagements above Australia between 202nd Air Group and No. 1 Wing, 38 Spitfires were destroyed for the loss of six Zeros.

21st Air Flotilla (Kōkūtai)

Bases: Tarakan, Borneo, Makassar, Sulawesi

Numbers: Included various aircraft types, with an estimated 30-40 Zeros.

Commander:

Rear Admiral Sadayoshi Yamada - Overall commander, with direct command through subordinates.Kanoya Air Group was part of 21st Air Flotilla

Bases: Kanoya Japan, Hankou China, Saigon French Indochina, Kendari Sulawesi, Kavieng New Ireland, Rabaul New Britain.

The Kanoya Air Group (鹿屋海軍航空隊, Kanoya Kaigun Kōkūtai) was an aircraft and airbase garrison unit of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS) during the Second Sino-Japanese War and Pacific campaign of World War II. The air group was redesignated as the 751st Air Group on 1 October 1942. On 1 November, the group's fighter unit was redesignated to the 253rd Air Group, while the bomber unit remained the 751st Air Group.

The Kanoya Air Group was formed on 1 April 1936 and was the oldest medium bomber (rikko) air group in IJNAS, along with the Kisarazu Air Group. It initially operated from Kanoya on Kyushu and was equipped with Type 96 Mitsubishi G3M medium bombers. They first saw combat during the Second Sino-Japanese War in August 1937. In July 1941, the air group temporarily moved to an airfield near Hankou in Central China to participate in Operation 102, which involved concentrated attacks against targets in Chongqing and Chengdu in West China.

Following the unit's return from Hankou to Kanoya in September 1941, they became the second IJNAS unit (after Takao Air Group) to be equipped with the new Type 1 Mitsubishi G4M medium bombers. In November, they moved to Taiwan, however soon afterwards the unit's main body was transferred to Saigon in French Indochina, leaving a detachment at Taichung. The detachment that stayed on Taiwan participated in the attack on the Philippines.

At the start of Pacific War, Kanoya Air Group was considered the most highly trained medium bomber unit in torpedo attacks. Therefore, its main body at Saigon was selected as the main torpedo attack unit for the attack on the newly arrived British naval Force Z, centered around the battleship HMS Prince of Wales and battlecruiser HMS Repulse. The attack formation of 26 G4M bombers was led by the unit's Hikōtaichō Lieutenant Commander Shichiso Miyauchi, who flew as an observer in the lead aircraft, piloted by Buntaichō Lieutenant Miyoshi Nabeta. By the time they arrived at the area off the south-east coast of Malay Peninsula, where the ships were heading back to Singapore, the Royal Navy ships had been already attacked by the older G3M bombers from Mihoro Air Group and Genzan Air Group. A high-level attack by Mihoro's bombers hit Repulse with a single 250 kg bomb that caused minor damage, while Genzan's bombers hit Prince of Walse with two torpedoes that hindered her steering ability. Kanoya's torpedo attack then hit Repulse with four torpedoes and finished off Prince of Walse with additional four torpedoes. The attack sank both battleships at the cost of two Kanoya bombers.

In January 1942, the detachment first moved to the newly captured airfield at Davao and then to Kendari and participated in the invasion of Dutch East Indies, while the main body supported the Japanese invasion of Malaya and Singapore. On 19 February, the detachment participated in the Bombing of Darwin, where they hit the harbor one and a half hours after the carrier strike. In March, the main body and the detachment both returned to Japan where they reunited.

On 12 September 1942, Kanoya Air Group's advanced detachment of medium bombers led by Buntaichō Lieutenant Osamu Doki moved to Rabaul on New Britain to participate in Guadalcanal campaign and New Guinea campaign. The rest of the group's bombers under Hikōtaichō Lieutenant Commander Kazuo Nishioka moved to Kavieng on New Ireland on 16 September. On the same day, part of its fighter unit led by Hikōtaichō Lieutenant Toshitaka Itō moved to Rabaul for temporary duty with Tainan Air Group. The group's bombers participated in major raids against Guadalcanal on 13 and 28 September, and against Port Moresby on 21 September. In the meantime, its fighters participated in an escort mission on 28 September and a fighter sweep against Guadalcanal on 29 September. On 1 October the unit was redesignated to 751st Air Group. Further fighter sweeps against Guadalcanal were conducted on 3 and 9 October and an escort on 23 October, while the bombers participated in major raids on 11, 13 and 14 October. On 1 November, the group's fighter unit was redesignated to the 253rd Air Group, while the bomber unit remained the 751st Air Group.

On 30 January, the 751st Air Group bombers were involved in the Battle of Rennell Island, where they were led by Lieutenant Commander Kazuo Nishioka and they torpedoed the cruiser Chicago. In April 1943, the unit participated in Operation I-Go. By mid-1943, the high rate of attrition forced the unit to reduce the number of aircrew per bomber from seven to five, which typically meant there was no co-pilot. 253rd Air Group fighters saw heavy fighting during the defence of Rabaul in late 1943 and early 1944. After US carrier force raided Truk Lagoon in February 1944, all air units were withdrawn from Rabaul area, including 751st Air Group.

23rd Air Flotilla (Kōkūtai)

Bases: Balikpapan, Borneo, Kendari, Sulawesi

Numbers: Similar to the 21st, with around 30-40 Zeros.

Commander:

Rear Admiral Eiji Gotō - Led operations across the Dutch East Indies.The Takao Air Group (高雄航空隊, Takao Kōkūtai) was part of the 23rd Air Flotilla (Kōkūtai)

The Takao Air Group (高雄航空隊, Takao Kōkūtai) was a unit of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS) during the Pacific War that was involved in the Philippines campaign, Dutch East Indies campaign, air raids on Australia, and the Guadalcanal Campaign. The air group was redesignated as the 753rd Air Group on 1 October 1942.

Southeast Asia

The group was formed on 1 April 1938 as a medium bomber unit and was initially equipped with Mitsubishi G3M bombers. In May 1940, it became the first unit to receive the new Mitsubishi G4M bombers. In 1941 the unit moved to Hankou to participate in operations in Central China.

Prior to the outbreak of Pacific War, half of the group was sent to Saigon, Indochina to participate in invasion of Malaya, while the other half was stationed at Kaohsiung on Taiwan to participate in the invasion of Philippines. On 8 December, the group's Hikōtaichō Lieutenant Commander Tarō Nonaka led 27 Takao medium bombers in an attack against Iba Airfield. They were escorted by Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters from 3rd Air Group, which would continue to operate together as part of 23rd Air Flotilla. They attacked various targets in the Philippines until 28 December. From 29 December to 6 January, they focused on bombing Allied positions on Corregidor. Throughout the rest of January, they conducted sorties against targets on Borneo and in February moved their focus on Java in Dutch East Indies. On 27 February, Lieutenant Jirō Adachi led 16 medium bombers in a level bombing attack on the US seaplane tender Langley, which sank her.

On 14 March, one half of the group moved to Kupang on Timor to make attacks on Northern Australia. The other half moved back to the Philippines to help break the Allied resistance on Bataan and Corregidor. After the Allied forces surrendered to the Philippines, this half of the group moved to Kupang on 17 April in order to join the other half in Air raids on Australia

Australia 1942

The first major raid occurred on 16 March, where Lieutenant Hiroshi Mine led 14 medium bombers against Darwin. There were no enemy fighters yet stationed at Darwin at that time, thus they suffered no losses. This soon changed with the arrival of USAAF 49th Pursuit Group equipped with Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighters. In an unescorted raid of seven medium bombers on 28 March, the group suffered one bomber shot down by the intercepting enemy fighters. From that point on, all daytime raids were escorted by fighters from the 3rd Air Group. Similar smaller raids were conducted on 30 and 31 March and 4 and 5 April, where they suffered a loss of three bombers out of six on the 4th. On 25 April, the group's new Hikōtaichō Lieutenant Commander Gorō Katsumi led a formation of 24 G4M medium bombers to attack Darwin, where they were intercepted by a large force of Warhawks that shot down four bombers. Two days later, Lieutenant Tanemasa Hirata led 16 medium bombers to attack Darwin. The raid was again intercepted by a large force of Warhawks, but this time 3rd Air Group fighter did their job well and no bombers were shot down. When the Allies started to raid the Kupang airfield in return, Takao Air Group (as well as the 3rd Air Group) moved further back to Kendari. In addition, raids on Darwin were suspended until June in order for Takao Air Group to replenish the lost aircraft.

On 13 June, the raids against Darwin resumed and Lieutenant Commander Katsumi led 27 medium bombers to attack an airfield there. On 15 June, Lieutenant Hirata led 27 medium bombers in another major raid on Darwin. The next day, Lieutenant Hirata again led 27 bombers to escort 27 G4M medium bombers there. In all these three major raids a large number of Warhawks intercepted the formations but no losses to the bombers occurred. In defense of the bombers, the escorting Zero fighter from the 3rd Air Group managed to shoot down 10 Warhawks for the loss of two of their own in return. No further daytime attacks were conducted until 30 July, when Lieutenant Commander Katsumi led 26 G4M medium bombers in a major raid on Darwin. The final daytime raid on Darwin occurred on 23 August, when Lieutenant Hirata led 27 G4M medium bombers and the intercepting Warhawks managed to shoot down one bomber. At that point, all further operations against Darwin were suspended until 1943.

Guadalcanal 1942

As the fighting over Guadalcanal intensified, 23rd Air Flotilla loaned a portion of 3rd Air Group to 25th Air Flotilla at Rabaul. On 22 September, Lieutenant Shigeji Makino brought a detachment of 20 medium bombers to Rabaul. Their first mission against Guadalcanal was flown on 27 September, when a combined force of 18 medium bombers from Kisarazu and Takao Air Groups under the command of Lieutenants Miyoshi Nabeta (Kisarazu) and Makino attacked Guadalcanal. They were intercepted by a large force of US Marine and US Navy Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters, which resulted in two bombers being shot down. The next day, a combined force of 27 medium bombers from Kisarazu, Kisarazu and Takao Air Groups attacked Guadalcanal again. This time five bombers were lost to 35 intercepting Wildcat fighters.

On 1 October, the unit was redesignated as the 753rd Air Group. The group's bombers aborted two major raids on 11 and 12 October due to bad weather. However, on 13 October Lieutenant Makino led a combined force of 27 medium bombers from 753rd, Kisarazu and Kisarazu Air Groups that bombed Henderson Field on Guadalcanal and damaged dozen of aircraft on the ground as well as destroyed significant fuel storage. On 15 October, Lieutenant Makino again led another attack on Guadalcanal, this time with 23 medium bombers from 753rd, Kisarazu and Kisarazu Air Groups. The last mission against Guadalcanal for 753rd Air Group was on 25 October, before the detachment returned to their base in East Indies.

Australia 1943

At the beginning of 1943, the 753rd Air Group again began operations against Darwin in Australia. This time they faced newly arrived Supermarine Spitfire fighters from RAAF No. 1 Wing. On 15 March, Lieutenant Kawamoto led 16 medium bombers to attack Darwin. On 2 May, Lieutenant Hirata led 25 medium bombers in another mission against Darwin. The raids resumed one month later on 28 June with nine medium bombers. On 30 June, Lieutenant Hirata led 23 medium bombers in a major raid targeting Fenton Airfield south of Darwin. Another raid on Fenton was conducted on 6 July, when Lieutenant Hirata led 26 medium bombers to bomb the airfield. In these raids during 1943, the escorting Zeros from 202nd Air Group (ex-3rd) protected the bombers well, since only four were lost. Furthermore, they completely outmatched Spitfires, since 38 of them were shot down for the loss of six Zeros. From 6 July, the 753rd Air Group suspended daytime raids and continued with night raids only.

1st Air Group (Kōkūtai)

The 1st Air Fleet (第一航空艦隊, Daiichi Kōkū Kantai), also known as the Kidō Butai ("Mobile Force"), was a combined carrier battle group comprising most of the aircraft carriers and carrier air groups of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during the first eight months of the Pacific War.

At the time of its best-known operation, the attack on Pearl Harbor, in December 1941, the 1st Air Fleet was the world's largest fleet of aircraft carriers.

In its second generation, 1st Air Fleet was a land-based fleet of "kichi kōkūtai" (base air unit(s)).

Bases: Palembang, Sumatra

Numbers: About 20-30 Zeros, involved in paratroop operations.

Commander:

Commander Ryūnosuke Kusaka - Associated with operations in Palembang.Origins

In 1912, the British Royal Navy had established its own flying branch, the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS). The IJN was modeled on the Royal Navy and the IJN Admiralty sought establishment of their own Naval Air Service. The IJN had also observed technical developments in other countries and saw military potential of the airplane. In 1913, the IJN seaplane carrier Wakamiya was converted into a seaplane tender and aircraft were purchased. The 1st and 2nd Air Fleet were to be the primary attack force of the IJNAS.

The Japanese carriers' experiences off China had helped further develop the IJN's carrier doctrine. One lesson learned in China was the importance of force concentration and mass in projecting naval air power ashore. Therefore, in April 1941 the IJN formed the 1st Air Fleet to combine all of its fleet carriers under a single command. The IJN centered its doctrine on air strikes that combined the air groups within carrier divisions, rather than each individual carrier. When more than one carrier division was operating together, the divisions' air groups were combined with each other. This doctrine of combined, massed, carrier air attack groups was the most advanced of its kind of all the world's navies. The IJN, however, remained concerned that concentrating all of its carriers together would render them vulnerable to being wiped out all at once by a massive enemy air or surface strike. Thus, the IJN developed a compromise solution in which the fleet carriers would operate closely together within their carrier divisions but the divisions themselves would operate in loose rectangular formations, with approximately 7,000 metres (7,700 yd) separating the carriers from each other.

Although the concentration of so many fleet carriers into a single unit was a new and revolutionary offensive strategic concept, the First Air Fleet suffered from several defensive deficiencies which gave it, in Mark Peattie's words, a "'glass jaw': it could throw a punch but couldn't take one." Japanese carrier anti-aircraft guns and associated fire control systems had several design and configuration deficiencies which limited their effectiveness. The IJN's fleet combat air patrol (CAP) consisted of too few fighter aircraft and was hampered by an inadequate early warning system, including a lack of radar. Poor radio communications with the fighter aircraft inhibited effective command and control of the CAP. The carriers' escorting warships were deployed as visual scouts in a ring at long range, not as close anti-aircraft escorts, as they lacked training, doctrine, and sufficient anti-aircraft guns. These deficiencies would eventually doom Kaga and other First Air Fleet carriers.

As a Carrier-Based Fleet

The First Air Fleet (Dai-ichi Kōkū Kantai) was a major component of the Combined Fleet (Rengō Kantai). When created on 10 April 1941, it had three kōkū sentai (air flotillas; in the case of aircraft carriers, carrier divisions): On that date, First Kōkū Sentai consisted of Akagi and Kaga and their aircraft units. Later that spring, a number of destroyers were added. On 10 April 1941, Second Kōkū Sentai comprised Sōryū, Hiryū and the 23rd Kuchikutai (Destroyer Unit). Fourth Kōkū Sentai consisted solely of light carrier Ryūjō and her aircraft unit, until two destroyers were added in August. (At its inception, First Air Fleet did not include Third Kōkū Sentai and it did not include it on 7 December 1941. Third Kōkū Sentai (3rd Carrier Division, see table below) was attached to First Fleet, as distinct from First Air Fleet. On 1 April 1942, Third Kōkū Sentai was disbanded.Imperial Flattops) See the table titled "Transition", below.

When formed on 10 April 1941, First Air Fleet was a naval battlegroup with the single most powerful concentration of carrier-based aircraft in the world at the time. Military historian Gordon Prange called it "a revolutionary and potentially formidable instrument of sea power."

Fifth Kōkū Sentai (5th Carrier Division) was created on 1 September 1941 and was added to First Air Fleet The Naval Data Base:航空戦隊.. When the new aircraft carrier Zuikaku was added to Fifth Kōkū Sentai, First Air Fleet consisted of Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, Hiryū, Ryūjō, Kasuga Maru (renamed Taiyō ca. 31 August 1942), Shōkaku and Zuikaku, along with their aircraft units and a number of destroyers.The Naval Data Base:航空戦隊. On 25 September 1941, Kasuga Maru was transferred from Fifth Kōkū Sentai to Fourth Kōkū Sentai.Imperial Flattops (Kasuga Maru was used to ferry aircraft to distant Japanese bases and should not be considered a front-line aircraft carrier. The status of any aircraft unit that she may have had is unclear.Imperial Flattops) Light carrier Shōhō was added to Fourth Kōkū Sentai on 22 December 1941.Imperial lattops She was destroyed on 7 May 1942 in the Battle of the Coral Sea.Imperial lattops Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, and Hiryū were lost in the Battle of Midway.

Each Kōkū Sentai of First Air Fleet tended to include a pair of aircraft carriers, and each included the respective hikōkitai/hikōtai (aircraft/aviation unit(s)) of each aircraft carrier. Each Kōkū Sentai of First Air Fleet was a tactical unit that could be deployed separately or combined with other Kōkū Sentai of First Air Fleet, depending on the mission. For example, for operations against New Britain and New Guinea in January 1942, First Kōkū Sentai and Fifth Kōkū Sentai participated.

The number (from approximately two dozen up to approximately 80 aircraft) and type of aircraft varied, based on the capacity of the aircraft carrier. The large fleet carriers had three types of aircraft; fighters, level/torpedo bombers, and dive bombers. The smaller carriers tended to have only two types of aircraft, fighters and torpedo bombers.

At the beginning of the Pacific War, First Air Fleet included six fleet carriers: Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, Hiryū, Shōkaku, and Zuikaku, and two light carriers: Ryūjō and Kasuga Maru (later renamed Taiyō), as shown in the table below.

On 14 July 1942, First Air Fleet was converted into Third Fleet (第三艦隊) and Eighth Fleet (第八艦隊), and 2nd Carrier Division (first generation) and 5th Carrier Division were disbanded. On the same date, the Japanese Navy's front-line aircraft carriers and their aircraft units came under the command of the 3rd Fleet, which was created in its sixth generation on that date.

Kidō Butai

The Kidō Butai (機動部隊, "Mobile Strike Force") was the Combined Fleet's tactical designation for its combined carrier battle groups. The title was used as a term of convenience; it was not a formal name for the organization. It consisted of Japan's six largest carriers, carrying the 1st Air Fleet. This mobile task force was created for the attack on Pearl Harbor under Vice-Admiral Chūichi Nagumo in 1941. For the attack, the Kidō Butai consisted of six aircraft carriers (commanded by Chūichi Nagumo, Tamon Yamaguchi and Chūichi Hara) with 414 airplanes, two battleships, three cruisers, nine destroyers, eight tankers, 23 submarines, and four midget submarines. However, these escort ships were borrowed from other fleets and squadrons. It was the single most powerful naval fleet until four of the six aircraft carriers of the unit were destroyed in the disastrous Battle of Midway.

| Date | Lower Units | Lowest Units and Ships |

|---|---|---|

| 10 April 1941 (original) | 1st Carrier Division | Akagi, Kaga Destroyer Division 7: Akebono, Ushio |

| 2nd Carrier Division | Sōryū, Hiryū Destroyer Division 23: Kikuzuki, Uzuki |

|

| 4th Carrier Division | Ryūjō | |

| 10 December 1941 | 1st Carrier Division | Akagi, Kaga Destroyer Division 7: Akebono, Ushio |

| 2nd Carrier Division | Sōryū, Hiryū Destroyer Division 23: Kikuzuki, Uzuki |

|

| 4th Carrier Division | Ryūjō, Taiyō Destroyer Division 3: Shiokaze, Hokaze |

|

| 5th Carrier Division | Shōkaku, Zuikaku, Oboro, Akigumo | |

| 10 April 1942 | 1st Carrier Division | Akagi, Kaga |

| 2nd Carrier Division | Hiryū, Sōryū | |

| 4th Carrier Division | Ryūjō, Shōhō | |

| 5th Carrier Division | Shōkaku, Zuikaku | |

| 10th Cruiser-Destroyer Squadron | Nagara Destroyer Division 4: Nowaki, Arashi, Hagikaze, Maikaze Destroyer Division 10: Kazagumo, Makigumo, Yūgumo, Akigumo Destroyer Division 17: Urakaze, Isokaze, Tanikaze, Hamakaze |

|

| 14 July 1942 | disbanded | |

As a Land-Based Air Fleet

On 1 July 1943, the 1st Air Fleet was recreated as an exclusively land-based air fleet. It was intended to consist of nearly 1,600 aircraft when completed, but the war situation prevented it from reaching that figure, and the second generation of this fleet began with only two Kōkūtai: Dai 261 Kaigun Kōkūtai (a one-month-old Zerosen unit) and Dai 761 Kaigun Kōkūtai (a bomber unit that was created on the same day as this fleet was). On 30 September 1943, a cabinet meeting planned the Absolute National Defense Zone (絶対国防圏, Zettai Kokubōken) strategy. The plan intended the Kuril Islands, Bonin Islands, Mariana Islands, Caroline Islands, Biak, Sunda Islands and Burma to be unsinkable aircraft carriers. The 1st Air Fleet became the main force of this plan. However, it was soundly beaten in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. The IJN then moved the air fleet to the Philippines to regroup. However, due partly to the aircrews' lack of combat experience, the air fleet suffered severe losses in the Formosa Air Battle. After the battle it had only 41 aircraft. The only tactic left for them was the kamikaze attack.

| Date | Higher unit | Lower units | Lowest units |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Jul-43 | Imperial General Headquarters | 261st NAG (Naval Air Group or Naval Aviation Group), 761st NAG | |

| 1-Jan-44 | Imperial General Headquarters | 121st NAG, 261st NAG, 263rd NAG, 265th NAG, 321st NAG, | |

| 341st NAG, 344th NAG, 521st NAG, 523rd NAG, 1021st NAG | |||

| 15-Feb-44 | Combined Fleet | 61st Air Flotilla | 121st NAG, 261st NAG, 263rd NAG, 321st NAG, 341st NAG, |

| 343rd NAG, 521st NAG, 523rd NAG, 761st NAG, 1021st NAG | |||

| 62nd Air Flotilla | 141st NAG, 262nd NAG, 265th NAG, 322nd NAG, 345th NAG, | ||

| 361st NAG, 522nd NAG, 524th NAG, 541st NAG, 762nd NAG | |||

| 5-May-44 | Combined Fleet | 22nd Air Flotilla | 151st NAG, 202nd NAG, 251st NAG, 253rd NAG, 301st NAG, |

| 503rd NAG, 551st NAG, 755th NAG | |||

| 26th Air Flotilla | 201st NAG, 501st NAG, 751st NAG | ||

| 61st Air Flotilla | 121st NAG, 261st NAG, 263rd NAG, 321st NAG, 341st NAG, | ||

| 343rd NAG, 521st NAG, 523rd NAG, 763rd NAG, 1021st NAG | |||

| 7-Aug-44 | Southwest Area Fleet | 22nd Air Flotilla | Higashi-Caroline NAG |

| 23rd Air Flotilla | Gōhoku NAG | ||

| 26th Air Flotilla | Hitō NAG | ||

| 61st Air Flotilla | Mariana NAG, Nishi-Caroline NAG | ||

| 153rd NAG, 201st NAG, 761st NAG, 1021st NAG | |||

| 15-Dec-44 | Southwest Area Fleet | 23rd Air Flotilla | Gōhoku NAG |

| 26th Air Flotilla | Hokuhi NAG, Chūhi NAG, Nanpi NAG | ||

| 153rd NAG, 201st NAG, 761st NAG, 1021st NAG | |||

| 1-Mar-45 | Southwest Area Fleet | 26th Air Flotilla | Hokuhi NAG, Chūhi NAG, Nanpi NAG, 141st NAG, 153rd NAG, |

| 201st NAG, 221st NAG, 341st NAG, 761st NAG, 763rd NAG | |||

| Taiwan NAG, 132nd NAG, 133rd NAG, 165th NAG, 634th NAG, | |||

| 765th NAG, 1021st NAG | |||

| 8-May-45 | Combined Fleet | 132nd NAG, 133rd NAG, 205th NAG, 765th NAG | |

| 15-Jun-45 | disbanded |

Operations

Pearl Harbor

The Kidō Butai (also known as the Carrier Striking Task Force) set sail from Hitokappu Bay, Japan under Vice Admiral Chūichi Nagumo on 26 November 1941, arriving in Hawaiian waters on Sunday, 7 December 1941 Hawaiian time. At around 8am, the first wave began its attack on the US Pacific Fleet based at Pearl Harbor and on outlying airfields. By the end of the day, 21 American ships were either sunk or crippled, 188 aircraft were destroyed, and almost 2,500 Americans were killed. Japan was now formally at war with the United States.

For the attack on Pearl Harbor, this fleet had a strength of 103 level bombers, 128 dive bombers, 40 torpedo bombers, 88 fighter planes, plus 91 planes for a total of 441 planes.

Bombing of Darwin

The Bombing of Darwin on 19 February 1942 was the largest single attack ever mounted by a foreign power on Australia. On that day, 242 Japanese aircraft, in two separate raids, attacked the town, ships in Darwin's harbour and the town's two airfields in an attempt to prevent the Allies from using them as bases to contest the invasion of Timor and Java. The town was only lightly defended and the Japanese inflicted heavy losses upon the Allied forces at little cost to themselves. The urban areas of Darwin also suffered some damage from the raids and there were a number of civilian casualties.

Indian Ocean Raid

Between 31 March and 10 April 1942 the Japanese conducted a naval sortie against Allied naval forces in the Indian Ocean. The Fast Carrier Task Force (Kidō Butai), consisting of six carriers commanded by Admiral Chūichi Nagumo, inflicted heavy losses on the British fleet, with the sinking of 1 carrier, 2 cruisers, 2 destroyers, and 23 merchant ships for the loss of 20 aircraft. Attacks on the island of Ceylon were also carried out.

Battle of the Coral Sea

The 1st Air Fleet dispatched the Fifth Carrier Division in the Coral Sea during the return from the Indian Ocean. On May 7 the USN sighted the Port Moresby invasion force and mistook it for the main carrier force. Admiral Fletcher sent an aircraft strike which sank the IJN light carrier Shōhō. After this loss of air cover, the Port Moresby invasion force abandoned its mission and retreated north. On the same day the IJN sighted and sank USN destroyer Sims and oiler Neosho. The primary action took place on 8 May. Both carrier forces sighted and attacked each other. As a result, Lexington was sunk and Yorktown was damaged by a Japanese air strike. USN aircraft managed to damage Shōkaku, meaning that she and her sister ship were unable to participate in the following operation. The remaining fleet returned to Japan to prepare for the Midway invasion (Operation MI).

Battle of Midway

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto planned to lure and destroy USN carriers by attacking the Midway Islands in June 1942. The Japanese were unaware that the United States had broken their naval code. As a result of this, USN carriers were already in the area when the Japanese attacked Midway. On 3 June US land-based bombers from Midway attacked the Japanese fleet but scored no hits. On 4 June, due to the poor reconnaissance efforts and tactical mistakes of Vice Admiral Chūichi Nagumo, USN dive bombers were able to surprise the Japanese carrier force and destroyed three carriers (Akagi, Kaga and Sōryū). At the time of the attack the Japanese carriers were in the process of preparing to launch an air strike against the US carriers and their hangars were full of loaded aircraft, bombs and aviation fuel which decisively contributed to their destruction. Carrier Hiryū managed to survive the attack and Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi launched a strike against Yorktown. Aircraft from Hiryū managed to cripple Yorktown, which was later sunk by Japanese submarine I-168. In response, the US launched a strike against Hiryū and sank her. That day the Japanese lost four aircraft carriers and much of their experienced aircrew.

Battle of the Philippine Sea

The US Navy's attack on the Japanese base at Truk (Chuuk) on 17 February 1944 (Operation Hailstone) surprised the Japanese military. In response, the Japanese Navy ordered all of the 61st Air Flotilla to the Mariana Islands. Its Number 261 Kaigun Kōkūtai (fighter) advanced to Saipan circa 19–24 February 1944, but attrition in air combats and illness weakened the unit greatly and it played only a minor role in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Elements of No. 263 Kaigun Kōkūtai (fighter) of the 61st Air Flotilla were stationed on Guam from 15 June 1944 and participated in the battle.

Battle of Leyte Gulf

After disastrous losses at the Battle of the Philippine Sea, the Japanese carrier force was again practically without aircrew and aircraft. This meant that at the Battle of Leyte Gulf the IJN carrier force was only used as a decoy force where it was ultimately destroyed, the battle that saw the last Kidō Butai survivor, Zuikaku, along with Zuiho, Chiyoda and Chitose succumbing to US air attacks of Admiral William F. Halsey's Task Force 38.

2nd Air Group (Kōkūtai)

The 2nd Air Group (第二航空隊, Dai-ni Kōkūtai) was a unit of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS) during the Pacific War that was involved in the Guadalcanal Campaign, Solomon Islands Campaign and New Guinea Campaign. The air group was redesignated as the 582nd Air Group on 1 November 1942.

Bases: Makassar, Sulawesi

Numbers: Similar to other groups, with around 20-30 Zeros.

Commander:

Commander Shigeharu Murata - Led operations in Makassar.History

The group was formed on 31 May 1942 in Yokosuka, Empire of Japan as a mixed fighter and dive bomber unit, where initial strength included 16 Aichi D3A dive bombers and 16 Mitsubishi A6M Zero (Model 32) fighters. The group was commanded by Lieutenant Fumito Inoue as Hikōtaichō, who also led the dive bomber squadron within the group. The fighter squadron was commanded by Lieutenant Akira Kurakane as Buntaichō. It was intended to serve as a garrison for New Caledonia after it would be captured in the planned Operation FS. After the disaster at Midway, the plan for Operation FS was canceled and the unit was ordered to move to Rabaul on New Britain. They embarked on the converted carrier Yawata Maru (later it became Un'yō) and were ferried to Rabaul. During the reorganization of the Imperial Japanese Navy on 14 July, the group was first assigned under the 8th Fleet, before it was transferred to the 25th Air Flotilla of 11th Air Fleet. They arrived at Rabaul on 6 August with 16 D3A dive bombers and 15 A6M3 Zero fighters, just one day prior to the unexpected Allied invasion of Guadalcanal and Tulagi. Prior to that, on 29 July, tanker No. 2 Nisshin Maru delivered further 20 Model 32 Zeros to be used by the group.

Since the 2nd Air Group possessed the new Model 32 Zeros with a reduced range compared to the older Model 21, they could not reach Guadalcanal and return to Rabaul, and neither could the dive bombers. Nevertheless, after being shocked by the unexpected invasion on 7 August, Rear Admiral Sadayoshi Yamada sent nine unescorted D3A dive bombers under the command of Lieutenant Inoue to strike the Allied shipping near Tulagi. This meant that each dive bomber carried only two 60 kg bombs, instead of a standing load of one 250 kg bomb, and more importantly, that they had to ditch near the Shortland Islands after the strike. Inoue's bombers attacked US destroyer Mugford off Tulagi and scored a single hit. However, they were intercepted by a dozen VF-5 and VF-6 Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters from US carriers that were covering the invasion force, where five D3A dive bombers were lost. The surviving four (including Inoue) then ditched near the Shortland Islands where they were picked up by the seaplane tender Akitsushima and one Kawanishi H8K flying boat.

The fighter squadron under Lieutenant Kurakane mainly served as Rabaul air defence until 22 August, after which they moved to temporarily support the Japanese operations around New Guinea; first, they operated from Lae and then from Buna airfields. Eight dive bombers under Lieutenant Inoue followed to Buna on 24 August. The group covered unsuccessful invasion of Milne Bay, before returning to Rabaul via Lae: bombers on 28 August and fighters on 8 September, respectively. When the airfield at Buka was available to stage from, 21 Model 32 Zeros and five D3A moved there on 29 September to cover the build-up of Shortland harbor and to provide air cover for resupply convoys bound for Guadalcanal. For example, they covered high-speed transport Nisshin when it delivered heavy equipment to Guadalcanal on 3 and 8 October, after which they withdrew to Rabaul and 6th Air Group took over the Buka–Bougainville area.

In the meantime, the rest of the group used borrowed Model 21 Zeros to escort periodic raids against Guadalcanal. On 12 September, Lieutenant Kurakane led 15 Zero fighters (including three from 6th Air Group) to escort 26 Mitsubishi G4M medium bombers to Rabaul. The ensuing air combat with 28 Wildcat fighters from Henderson Field resulted in six bombers and one Zero lost, while two Wildcats crashed. Two days later, on 14 September, Lieutenant Kurakane made a reconnaissance sweep over Guadalcanal to see if the ground forces under Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi managed to capture Henderson Field. Another fighter sweep was made on 27 September but Lieutenant Kurakane's 12 Zeros missed the combat. On 11 October, Lieutenant (jg) Tokitane Futagami led eight 2nd Air Group fighters in a large strike consisting of 45 G4M bombers and 29 Zeros against Guadalcanal. On 14 October, Lieutenant Kurakane led 15 Zeros to escort 26 G4M bombers in a periodic raid against Rabaul, where the ensuing air combat resulted in the loss of three bombers and one Wildcat. On 20 October, Lieutenant (jg) Futagami led 13 Zeros (including six of Tainan Air Group) to escort nine G4M bombers to Guadalcanal, while the next day 2nd Air Group Zeros participated in a similar raid.

On 22 October, the group's dive bombers operating from Buin took part in an anti-shipping strike against Guadalcanal, where six D3A under Reserve Lieutenant (jg) Ekai Yoshikawa joined another six from 31st Air Group under Reserve Lieutenant Norimasa Kitamura. The dive bombers attacked the destroyer Nicholas but failed to score any hits. The escorting Zero fighters under Lieutenant Mitsugi Kofukuda from the 6th Air Group failed to protect them against the intercepting Wildcat fighters, which resulted in the loss of two dive bombers.

On 1 November 1942, the 2nd Air group was redesignated as the 582nd Air Group. Under the new name, the air group continued to participate in Guadalcanal Campaign. The group was involved in the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, where they first protected the crippled battleship Hiei and then Rear Admiral Raizō Tanaka's transports carrying fresh troops and supplies to Guadalcanal. In both cases, the patrols consisted of Zero fighters and were led by Warrant Officer Kazuo Tsunoda. Lieutenant Kurakane was injured in a landing accident on 11 November after leading 582nd fighters to escort medium bombers to Guadalcanal

By mid-November, the 582nd Air Group incorporated aircrew and aircraft from other dive bomber units, i.e., the 954th (ex-31st) Air Group and 956th (ex-35th) Air Group. The aircraft strength was increased to 24 dive bombers and 36 fighters. Newly promoted Lieutenant Commander Inoue remained the group's Hikōtaichō and commanded the dive bomber squadron, while Lieutenant Saburō Shindō (Kurakane's replacement) commanded the fighter squadron. Lieutenant Tatsuo Takahata (ex-35th) and Reserve Lieutenant Kitamura (ex-31st) became Buntaichō in the dive bomber squadron, while Lieutenant (jg) Usaburō Suzuki was Buntaichō in the fighter squadron. When Allies started the offensive against Buna–Gona on 16 November 1942, Lieutenant Commander Inoue led nine dive bombers from Rabaul to attack Allied supply ships east of Buna on New Guinea. Afterwards, the 582nd Air Group moved to Lae and on 17 November made another attack on the ships. From there, they made several raids with D3A dive bombers and Zeros against Allied ground forces. They returned to Rabaul on 28 November but continued to conduct attacks on Buna until the end of December. Lieutenant Commander Inoue and Reserve Lieutenant Kitamura led most of the missions.

In February 1943, the group was involved in covering the evacuation of Japanese troops from Guadalcanal. While leading 15 dive bombers in an attack on Allied ships near Savo Island on 1 February, Lieutenant Kitamura was shot down and killed in action, along with four other dive bombers. However, they sank one destroyer and damaged another one. The escorting Zeros under Lieutenants Shindō and Suzuki managed to shoot down three Wildcats for the loss of three of their own.

In April 1943, the group participated in Operation I-Go. On 7 April, the group's new Hikōtaichō, Lieutenant Tatsuo Takahata, led 17 dive bombers against Allied shipping around Tulagi, which were escorted by Suzuki's 21 Zeros. The intercepting Allied fighters accounted for four dive bombers (including Takahata) and one Zero shot down. The group's fighters escorted medium bombers in raids against Port Morseby and Milne Bay on 12 and 14 April, respectively. During the Operation SE on 16 June, the group's 24 D3A dive bombers under Lieutenant Tamotsu Ema made a strike against Allied shipping around Guadalcanal, where the group's new Hikōtaichō, Lieutenant Commander Saburō Shindō, led 16 Zeros to escort them. They lost 13 dive bombers and four Zeros in the attack.

Finally, the group's fighter unit was disbanded on 1 August 1943 and some pilots were transferred to 201st and 204th Air Groups. The group then became a fully bomber unit and later on also absorbed Aichi D3A dive bombers and Nakajima B5N and B6N torpedo bombers from other units, such as from Ryūhō and Jun'yō Air Groups on 1 September. It continued to participate in the Solomon Islands campaign and New Guinea campaign, including in attacking Allied ships during landings on Rendova, on New Georgia, on Vella Lavella, at Lae, at Arawe, at Finschhafen and finally at Cape Torokina.

Additional Notes:

Operational Fluidity: Numbers are estimates; units often moved or combined for operations. Exact numbers changed due to losses, maintenance, and redeployment.

Support and Auxiliary Units: There were also smaller detachments with Zeros for reconnaissance or escort, less documented.

Carrier-Based Units: Some Zeros operated from carriers during invasions but were not long-term based in the Dutch East Indies.

Late War Operations: Unit composition became more fluid, with fewer specialized groups due to defensive demands.

Kamikaze Units: Towards the war's end, some Zeros or pilots might have been reassigned for kamikaze missions, more prevalent for Japan's defense.Other Notable Figures:

Captain Minoru Genda - Involved in planning air operations, later commanded the elite 343rd Air Group.

Lieutenant Hiroyoshi Nishizawa - A top ace from the 253rd Air Group, operating in the region, known for combat influence rather than command.The command structure was fluid, with officers often in temporary or shifting roles for specific operations, affecting direct command over Zero units.

The Buffalo’s fight to the End.

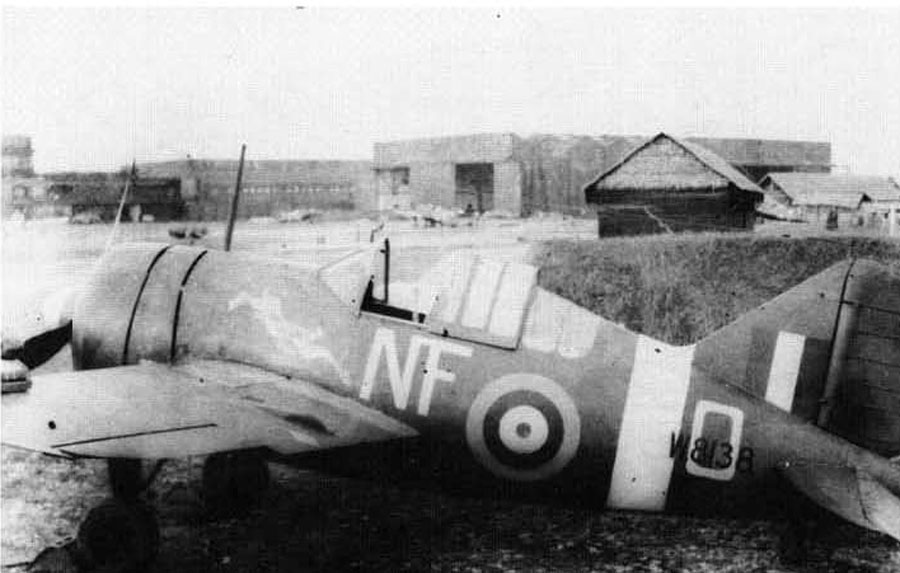

Brewster F2A Buffalo

POLISH & ENGLISH PUBLICATION by Andre R. Zbiegniewski published by Kagero

The orders placed with the USA by the British purchasing delegation in the early spring of 1940 included, among others, 170 unequipped Brewster F2A-2s. This gave birth to an un-naval version which the manufacturer named the Model 339E, whereas the recipient, Buffalo Mkl.

After being fitted with such add-ons as cockpit and fuel tanks armor as well as a heavier Hamilton Standard propeller, it was the heaviest F2A of all (ca. 3,100 kg). The RAF department of supplies gave the aircraft serial numbers W8131-W8250 and AN168-AN221.

Apart from the first three machines, sent for tests to the British Isles, the remaining 167 were shipped straight from the factory to RAF depots in Singapore in April 1941. The forming of five Buffalo squadrons as set out in plans of Malayan defense was going quite smoothly.

Only 154 fighters survived until the autumn, when all these units were finally in combat readiness. At least twenty had been lost in flying accidents, whereas three had probably been reconstructed to perform photo reconnaissance tasks. They were then assigned to the newly formed 4 PRU (Photo Reconnaissance Unit).

The warfare which began on December 8, 1941 (December 7 in Pearl Harbor’s time zone) with a Japanese landing on the north-eastern coast of the Malayan Peninsula saw the Buffalo squadrons thrown into the very midst of combat. The greatest pressure was exerted upon the north-based elements of 21 Sqn RAAF and 243 Sqn RAF.

Having learned about the landing of considerable enemy forces on the beaches around the river Kemassin estuary, a few Buffalos of 243 Sqn were deployed there from Kota Bharu soon after dawn. Flt Off Holder’s WP-U (W8196) and Flt Off Shield’s WP-X (AN221) fell like a pair of hawks upon the troop-filled beaches, machine-gunning and even causing temporary panic among the enemies.

However, the Buffalo’s low capability to withstand (even small-caliber) ground fire was soon discovered. A few accidental hits by rifle bullets were enough to put Holder’s aircraft out of the game, obliging him to immediately break up his mission and return home in an unstable machine. An attempt to land with damaged brakes on the Kota Bharu strip ended in WP-U’s collision with the wreckage of a Hudson from 1 Sqn RAAF.

Anxious for his comrade, Flt Off Shield considered the task completed and he, too, headed back for the base. However, WP-X’s engine now began to choke, throwing out oil, which gradually covered the windshield. Experiencing limited forward visibility, the pilot had to open the canopy.

Looking around for bearings, he was surprised to see nine unescorted bombers a little below. “They were flying in an ideal formation, like on a training flight, showing their uniformly pearly (rather light grey - author’s note) camouflage. The tops of their tails were decorated with yellow patterns. I identified the twin-engined aircraft as Ki-21s". They probably belonged to 3 Chutai/62 Sentai, returning from a raid on Machang.

Despite his unfavorable position, Shield was determined to attack. Only on approaching the enemy to within the effective fire range (300 m) did he see that his weapons were not working. He could but return to base. This way the indifferent fate left unused the first opportunity to open the Buffalo’s Far-Eastern tally.

Not long before dawn on December 8, Singapore experienced the first raid. Approaching the metropolis after an almost 1,000 km long flight, the Mihoro Kokutai bombers had been plotted early enough by British radars. Unfortunately, there was no man at the RAF HQ who was determined to do something about it.

The seventeen G3Ms arrived over the island from north-west, finding a richly illuminated city, which nobody had taken care to prepare for such a possibility. Three Buffalos from 453 Sqn RAAF which were waiting at readiness on the Sembawang air strip did not scramble to intercept the aggressors because... the British commander of the base had forbidden it (!). Two hundred were killed or wounded by bombs in the city and at adjacent airfields.

Mounting a RAF counterattack against the Japanese beachhead in the north of Malaya continued well into the morning. After bombers and fighters had taken off from Kuantan and Sungei Patani, four Buffalos of 21 Sqn RAAF were left to defend the latter. The pilots of two - Flt Lt. Hooper in GA-D (AN194) and Flt Off Kirkman in GA-K (AN201) - turned out to be the only ones who were determined to take off.

It came out soon when Japanese bombers suddenly emerged low above the airfield dropping a multitude of fragmentation bombs. Mottled grey and green, the Ki-21s of 98 Sentai majestically passed over the base, completely disregarding the sparse and inaccurate AA fire. Despite bombs ripping the ground and debris whizzing about, Hooper’s and Kirkman’s barrelish fighters rolled onto the runway. Both aircraft got airborne to a great astonishment of the RAF personnel, who cringed in shelters.

Engines moaning at full throttle, the pilots arduously closed on the re-approaching formation from astern. The twin-engined bodies grew larger in their gunsights. Light grey, green-striped fuselages were adorned with horizontal blue waves on the tails - the emblem of the staff Chutai of 98 Sentai. To be on the safe side, the Buffalos approached to less than 300 meters.

The enemy gunners would open fire any moment now. Meanwhile, the fighters unlock their weapons, press the triggers and... nothing - complete silence! All machine guns on both fighters jammed. What a damn luck! - both Australians will keep saying on return to base.

Prior to this, however, the bombs of 98 Sentai, unmoved by the vain action of the two Buffalos, affected Sungei Patani quite badly. They hit No. 21 Sqn aircraft stowed at the highest, and therefore the driest, point of the boggy airfield. Two Buffalos were totally destroyed, while five were heavily damaged. Two pilots and sixteen civilian workers were killed in airfield buildings hit by bombs.

On the morning of December 8 the Singapore-based RAF HQ deployed aircraft of the 4 PRU to reconnoiter over other north-Malayan beaches suitable for landing operations. The Singora region was to be photographed by Sgt Wareham in an unarmed Buffalo W8166. To his extreme surprise, he found the assigned stretch of coastline crowded with anchored (40) warships, landing craft, large seaplanes and Japanese landing troops. Their head was already advancing from the established beachhead towards the south-east.

They even had aerial cover, which was soon discovered by Flt Lt. Kinninmont and his wingman, Sgt. Chapman of 21 Sqn RAAF, who were caught in an ambush set over the southern approach to Singora by twelve Ki-27s from 11 Sentai loitering around. The Japanese fighters rushed wildly on the two Buffalos, getting in each other’s way. Hampering one another in keeping effective fire, they enabled the Australians to escape the dire straits in a mad dive almost to the ground. Covering the remaining distance just above the palm tree tops, Kinninmont’s and Chapman’s shot-up aircraft managed to reach Sungei Patani.

There, they experienced another raid by over twenty Japanese bombers at 10.45. Since there had been no earlier warning, the commander of 21 Sqn would not allow the five ready Buffalos to scramble under the shower of bombs. This way, the undisturbed raiders systematically destroyed buildings, depots, and air strips of the airfield. The few still serviceable RAF aircraft and the remains of 21 Sqn began preparations for a southward evacuation.

Next day they found themselves at Butterworth base, situated on the west coast, where they would soon experience the same situation. On December 8 Kinninmont attempted to make a last reconnaissance sortie in a Buffalo GA-? (W8232). Appearing to the south of Singora, this A flight machine of 21 Sqn was chased away by very active Ki-43s of 59 Sentai.

On the afternoon of December 9, four Buffalos of 21 Sqn returning from a recalled escort mission for Singora-targeting RAF bombers encountered Japanese fighters over Butterworth. Taking advantage of the element of surprise, the Ki-27s quickly brought down in flames Flt Lt. McKenny’s aircraft (W8224, probably GA-G). The pilot bailed out and landed in the bay. Flt Lt. Williams in GA-? (W8232) was shot down next and crashed upon force-landing, the pilot surviving.

There being a multitude of attackers, Flt Off Montefiore decided to maintain constant fire. Convinced that he would not leave the battlefield alive, anyway, he was not afraid to overheat his machine guns. Fire bursting forth, his burst framed one of the head-on attacking Ki-27s. Small explosions appeared at its starboard wing root, and one of the main legs broke off. The Japanese shook and plunged down, pouring smoke from under the cowling. All that lasted a few seconds.

Right after that, equally accurate bursts of some 11 Sentai pilot drummed on the Buffalo W8236’s engine cowling. Flames burst in the Australian’s face, he abandoned the aircraft as fast as he could. His parachute canopy soon hanged from a tall palm. What a coincidence - landing amidst coconut palms. But at the same time, how great the joy of having survived.

A badly shot-up fourth Buffalo made an arbitrary landing on a rice field across the strait. The pilot returned to base by ferry, but GA-M (AN188), considered repairable at first, never again took to the air.

The loss of four 21 Sqn machines over Butterworth made the RAF authorities aware of the serious situation. Even in this part of Malaya, Japanese supremacy in the air was noticeable and overwhelming. A decision was made to withdraw still farther to the south. The remains of the British and Australian squadrons from northern Malaya occupied Ipoh airfield the next day. Everyone realized how low their combat value was. The personnel’s low morale combined with the primitive living conditions and unprepared airfield did not guarantee the necessary effectiveness when they would face another (failed) trial the day after.

On the late afternoon of December 8 the battleship HMS Prince of Wales and battle cruiser HMS Repulse departed Singapore with an escort, heading for the area of Japanese landings. The aerial cover guarantee that the RAF had given the Force Z commander, Adm. Phillips, was a false promise. Having been destroyed, majority of northern and central Malayan airfields were now out of service. The direct consequence of that was the known and often described massacre of the British group on December 9. The sinking of both dreadnoughts by Japanese aircraft, a thousand people being killed in the process, was the most painful blow struck to date at the British interests in the Far East.

Accidentally, Buffalo pilots of 243 Sqn RAF, 453 Sqn RAAF and 4 PRU witnessed this defeat. Called into action too late, they could but watch the thousands of men struggling in the water. The great victory of the Japanese air forces decided the fate of northern Malaya. Demoralized British units of all arms were retreating south in panic, the last Buffalo squadrons among them. Their airfields situated at the Thai border were being seized by the Japanese. With a whole lot of untouched inventory (fuel depots, ammunition depots and other equipment), this was “a completely unexpected gift from Churchill”.

The remains of 21 Sqn RAAF were joined at Ipoh by a flight of Buffalos from 243 Sqn RAF on December 12. Fit Off Holder, who commanded it, came with sergeants: Oliver, Fisken and Wipiti, and Fit Lt Phillips in W8166 of 4 PRU. Although assigned fighter-bomber duties at Singapore, the new-arrived five machines were mainly sent out for reconnaissance by their new commander. A more offensive attitude was taken next day (December 13) by 453 Sqn RAAF.

The squadron’s sixteen aircraft set out from Sembawang in the morning, ordered to reconnoiter over the Thai border area, and then land and remain at Ipoh. They were interrupted while refueling on an intermediate landing at Butterworth, and scrambled on a warning about enemy bombers approaching nearby Penang (across the strait). 453 Sqn’s leader, Fit Lt Vanderfield (TD-V, AN185), was first to notice the enemy and, diving without hesitation, he scored an inaugural victory. His victim was a single-engined Ki-51 bomber of 71 Chutai, another one, this time a Ki-48 of 75 Sentai, falling a moment later.

Three others were annihilated by two other Australians, one being Sgt Read in a Buffalo GA-F (W8209). The defeated Ki-51s were reported as “Stuka-type dive-bombers”. The five Buffalos landed at Butterworth a moment before thirty Ki-27s attacked. The leader of the Australians, Fit Lt Vigors, and his wingmen, Fit Lt Grace and Sgt O’Mara, decided to take off again. Climbing over the Penang island, the three Buffalos let pass the formation of 1 and 11 Sentais flying below at a minimal level.

After a flashing bunt, Vigors’ threesome gave chase, diving after the enemy. Covering one another, they managed to break up the Japanese formation and engage them. Fit Lt Vigors put a few accurate bursts in several opponents. Himself and ground onlookers would later confirm “three victories following these hits”. However, the Buffalo pilots were helpless regarding the excellent agility of the Ki-27. This resulted after a while in AN213, and thus also Vigors, becoming a target, one of the bullets setting the ventral fuel tank on fire. He bailed out of the burning aircraft literally at the last moment, landing in the jungle which covered a coastal mountain range to the north of the city.