Mitsubishi A6M Rei-sen 零式艦上戦闘機

The Mitsubishi A6M "Zero" is a long-range carrier-capable fighter aircraft formerly manufactured by Mitsubishi Aircraft Company, a part of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. It was operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) from 1940 to 1945. The A6M was designated as the Mitsubishi Navy Type 0 carrier fighter[1] (零式艦上戦闘機, rei-shiki-kanjō-sentōki), or the Mitsubishi A6M Rei-sen. The A6M was usually referred to by its pilots as the Reisen (零戦, zero fighter), "0" being the last digit of the imperial year 2600 (1940) when it entered service with the IJN. The official Allied reporting name was "Zeke", although the name "Zero" was used more commonly.

The Zero is considered to have been the most capable carrier-based fighter in the world when it was introduced early in World War II, combining excellent maneuverability, high airspeed, strong firepower and very long range.[2] The Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service also frequently used it as a land-based fighter.

In early combat operations, the Zero gained a reputation as a dogfighter,[3] achieving an outstanding kill ratio of 12 to 1,[4] but by mid-1942 a combination of new tactics and the introduction of better equipment enabled Allied pilots to engage the Zero on generally equal terms.[5] By the middle months of 1943 the deterioration of fighter pilot training in the IJNAS contributed to making the Zero less effective against newer Allied fighters. The Zero lacked hydraulic boosting for its ailerons and rudder, rendering it difficult to maneuver at high speeds. Lack of self-sealing fuel tanks also made it more vulnerable than its contemporaries. By 1944, the A6M had fallen behind Allied fighters in speed and was regarded as outdated but still capable if it had trained pilots. However, as design delays and production difficulties hampered the introduction of newer Japanese aircraft models, the Zero continued to serve in a front-line role until the end of the war in the Pacific. During the final phases, it was also adapted for use in kamikaze operations.[6] Japan produced more Zeros than any other model of combat aircraft during the war.[7]

Design and development

The Mitsubishi A5M fighter was just entering service in early 1937, when the Imperial Japanese Navy started looking for its eventual replacement. On 5 October 1937, it issued "Planning Requirements for the Prototype 12-shi Carrier-based Fighter", sending them to Nakajima and Mitsubishi. Both firms started preliminary design work while awaiting more definitive requirements a few months later.[8]

Based on the experiences of the A5M in China, the IJN sent out updated requirements in October, calling for a speed of 270 kn (310 mph; 500 km/h) at 4,000 m (13,000 ft) and a climb to 3,000 m (9,800 ft) in 9.5 minutes. With drop tanks, the IJN wanted an endurance of two hours at normal power, or six to eight hours at economical cruising speed. Armament was to consist of two 20 mm cannons, two 7.7 mm (.303 in) machine guns and two 60 kg (130 lb) bombs. A complete radio set was to be mounted in all aircraft, along with a radio direction finder for long-range navigation.[9] The maneuverability was to be at least equal to that of the A5M, while the wingspan had to be less than 12 m (39 ft) to allow for use on aircraft carriers.

Nakajima's team considered the new requirements unachievable and pulled out of the competition in January. Mitsubishi's chief designer, Jiro Horikoshi, thought that the requirements could be met, but only if the aircraft were made as light as possible. Every possible weight-saving measure was incorporated into the design. Most of the aircraft was built of a new top-secret aluminium alloy developed by Sumitomo Metal Industries in 1936. Called "extra super duralumin", it was lighter, stronger and more ductile than other alloys used at the time but was prone to corrosive attack, which made it brittle.[10] This detrimental effect was countered with a zinc chromate anti-corrosion coating applied after fabrication. No armour protection was provided for the pilot, engine or other critical points of the aircraft, and self-sealing fuel tanks, which were becoming common among other combatants, were not used. This made the Zero lighter, more maneuverable, and one of the longest-ranged single-engine fighters of World War II, which made it capable of searching out an enemy hundreds of kilometres away, bringing it to battle, then returning to its base or aircraft carrier. However, that tradeoff in weight and construction also made it prone to catching fire and exploding when struck by enemy fire.[11]

With its low-wing cantilever monoplane layout, retractable wide-set conventional landing gear, and enclosed cockpit, the Zero was one of the most modern carrier-based aircraft in the world at the time of its introduction. It had a fairly high-lift, low-speed wing with very low wing loading. Combined with its light weight, this resulted in a very low stalling speed of well below 60 kn (110 km/h; 69 mph). This was the main reason for its phenomenal maneuverability, allowing it to out-turn any Allied fighter of the time. Early models were fitted with servo tabs on the ailerons after pilots complained that control forces became too heavy at speeds above 300 kilometres per hour (190 mph). They were discontinued on later models after it was found that the lightened control forces were causing pilots to overstress the wings during vigorous maneuvers.[12]

Name

The A6M is usually known as the 'Zero' from its Japanese Navy aircraft type designation, Type 0 carrier fighter (Rei shiki Kanjō sentōki, 零式艦上戦闘機), taken from the last digit of the Imperial year 2600 (1940) when it entered service. In Japan, it was unofficially referred to as both Rei-sen and Zero-sen; Japanese pilots most commonly called it Zero-sen, where sen is the first syllable of sentōki, Japanese for 'fighter plane'.[Note 2][13] In the official designation 'A6M', the 'A' signified a carrier-based fighter, '6' meant that it was the sixth such model built for the Imperial Navy, and 'M' indicated Mitsubishi as the manufacturer.

The official Allied code name was 'Zeke', in keeping with the practice of giving male names to Japanese fighters, female names to bombers, bird names to gliders, and tree names to trainers. 'Zeke' was part of the first batch of 'hillbilly' code names assigned by Captain Frank T. McCoy of Nashville, Tennessee (assigned to the Allied Technical Air Intelligence Unit at Eagle Farm Airport in Australia), who wanted quick, distinctive, easy-to-remember names. The Allied code for Japanese aircraft was introduced in 1942, and McCoy chose 'Zeke' for the 'Zero'. Later, two variants of the fighter received their own code names. The Nakajima A6M2-N floatplane version of the Zero was called 'Rufe', and the A6M3-32 variant was initially called 'Hap'. General 'Hap' Arnold, commander of the United States Army Air Forces, objected to that name, however, so it was changed to 'Hamp'.

Operational history

The first Zeros (pre-series of 15 A6M2) went into operation with the 12th Rengo Kōkūtai in July 1940.[14] On 13 September 1940, the Zeros scored their first air-to-air victories when 13 A6M2s led by Lieutenant Saburo Shindo, escorting 27 G3M "Nell" medium-heavy bombers on a raid of Chongqing, attacked 34 Soviet-built Polikarpov I-15s and I-16s of the Chinese Nationalist Air Force, claimed 'all 27' of the Chinese fighters shot down without loss to themselves. However Major Louie Yim-qun had in fact nursed his I-15 riddled with 48 bullet holes back to base, and Lieutenant Gao Youxin claimed to have shot down one Zero, but at most 4 Zeroes sustained some damage in the 1/2 hour-long dogfight over Chongqing.[15] By the time they were redeployed a year later, the Zeros had shot down 99 Chinese aircraft[16] (up to 266 according to other sources).[14]

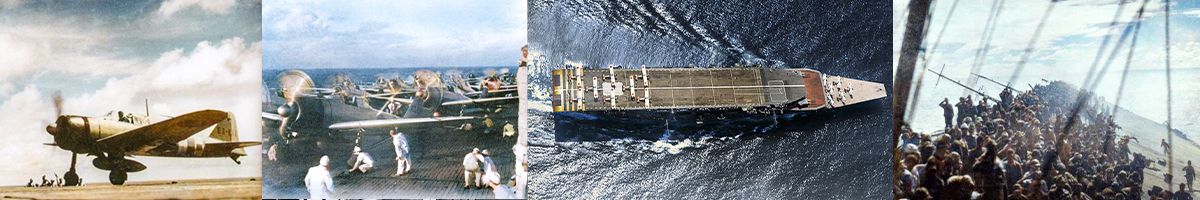

At the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, 521 Zeros were active in the Pacific, 328 in first-line units.[17] The carrier-borne Model 21 was the type encountered by the Americans. Its tremendous range of over 2,600 kilometres (1,600 mi) allowed it to range farther from its carrier than expected, appearing over distant battlefronts and giving Allied commanders the impression that there were several times as many Zeros as actually existed.[18]

The Zero quickly gained a fearsome reputation.[3] Thanks to a combination of unsurpassed maneuverability - compared to contemporary Axis fighters — and excellent firepower, it easily disposed of Allied aircraft sent against it in the Pacific in 1941.[19][20] It proved a difficult opponent even for the Supermarine Spitfire. "The RAF pilots were trained in methods that were excellent against German and Italian equipment but suicide against the acrobatic Japs", as Lieutenant General Claire Lee Chennault noted.[21] Although not as fast as the British fighter, the Zero could out-turn the Spitfire with ease, sustain a climb at a very steep angle, and stay in the air for three times as long.[22]

Allied pilots soon developed tactics to cope with the Zero. Because of its extreme agility, engaging a Zero in a traditional turning dogfight was likely to be fatal.[23] It was better to swoop down from above in a high-speed pass, fire a quick burst, then climb quickly back up to altitude. A short burst of fire from heavy machine guns or cannon was often enough to destroy the Zero, provided that some hits rupture the fuel tanks. These tactics were regularly employed by Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters during Guadalcanal defense through high - altitude ambush, which was possible with an early warning system consisting of coastwatchers and radar.[24] Such "boom-and-zoom" tactics were also successfully used in the China Burma India Theater by the 'Flying Tigers' of the American Volunteer Group (AVG) against similarly maneuverable Japanese Army aircraft such as the Nakajima Ki-27 "Nate" and Nakajima Ki-43 "Oscar". AVG pilots were trained by their commander Claire Chennault to exploit the advantages of their P-40 Warhawks, which were very sturdy, heavily armed, generally faster in a dive, and level flight at low altitude, with a good rate of roll.[25]

Another important maneuver was Lieutenant Commander John S. 'Jimmy' Thach's "Thach Weave", in which two fighters would fly about 60 m (200 ft) apart. If a Zero latched onto the tail of one of the fighters, the two aircraft would turn toward each other. If the Zero followed his original target through the turn, he would come into a position to be fired on by the target's wingman. This tactic was first used to good effect during the Battle of Midway and later over the Solomon Islands.

Many highly experienced Japanese aviators were lost in combat, resulting in a progressive decline in pilot quality, which became a significant factor in Allied successes. Unexpected heavy losses of pilots at the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway dealt the Japanese carrier air force a blow from which it never fully recovered.[26][27]

Throughout the Battle of Midway Allied pilots expressed a high level of dissatisfaction with the F4F Wildcat. Captain Elliott Buckmaster, commanding officer of USS Yorktown notes: "The fighter pilots are very disappointed with the performance and length of sustained fire power of the F4F-4 airplanes. The Zero fighters could easily outmaneuver and out-climb the F4F-3, and the consensus of fighter pilot opinion is that the F4F-4 is even more sluggish and slow than the F4F-3. It is also felt that it was a mistake to put 6 guns on the F4F-4 and thus to reduce the rounds per gun. Many of our fighters ran out of ammunition even before the Jap dive bombers arrived over our forces; these were experienced pilots, not novices."[28]

They were astounded by the Zero's superiority:[29] "In the Coral Sea, they made all their approaches from the rear or high side and did relatively little damage because of our armor. It also is desired to call attention to the fact that there was an absence of the fancy stunting during pull outs or approaches for attacks. In this battle, the Japs dove in, made the attack and then immediately pulled out, taking advantage of their superior climb and maneuverability. In attacking fighters, the Zeros usually attacked from above rear at high speed and recovered by climbing vertically until they lost some speed and then pulled on through to complete a small loop of high wing over which placed them out of reach and in position for another attack. By reversing the turn sharply after each attack the leader may get a shot at the enemy while he is climbing away or head on into a scissor if the Jap turns to meet it."[28]

In contrast, Allied fighters were designed with ruggedness and pilot protection in mind.[30] The Japanese ace Saburō Sakai described how the toughness of early Grumman aircraft was a factor in preventing the Zero from attaining total domination: "I had full confidence in my ability to destroy the Grumman and decided to finish off the enemy fighter with only my 7.7 mm machine guns. I turned the 20mm cannon switch to the 'off' position, and closed in. For some strange reason, even after I had poured about five or six hundred rounds of ammunition directly into the Grumman, the airplane did not fall, but kept on flying! I thought this very odd—it had never happened before—and closed the distance between the two airplanes until I could almost reach out and touch the Grumman. To my surprise, the Grumman's rudder and tail were torn to shreds, looking like an old torn piece of rag. With his plane in such condition, no wonder the pilot was unable to continue fighting! A Zero which had taken that many bullets would have been a ball of fire by now."[31]

When the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, armed with four "light barrel" AN/M2 .50 cal. Browning machine guns and one 20 mm autocannon, and the Grumman F6F Hellcat and Vought F4U Corsair, each with six AN/M2 .50 calibre Browning guns, appeared in the Pacific theater, the A6M, with its low-powered engine and lighter armament, was hard-pressed to remain competitive. In combat with an F6F or F4U, the only positive thing that could be said of the Zero at this stage of the war was that, in the hands of a skillful pilot, it could maneuver as well as most of its opponents.[18] Nonetheless, in competent hands, the Zero could still be deadly. Because of shortages of high-powered aviation engines and problems with planned successor models, namely the superior Mitsubishi A7M2 Reppū, the Zero remained in production until 1945, with over 10,000 of all variants produced.

Allied analysis

Chinese opinions

The Japanese deployed the A6M during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Inevitably some aircraft were lost, with at least two falling more-or-less intact into Chinese hands. The first known example, an A6M2 (the 12th of the 15 pre-production aircraft, Serial V-110), fell near Fainan Island. On 18 September 1940 a team, including Western volunteers assisting the Chinese, examined the wreck. It was largely intact, and a detailed report was compiled and sent to the U.S. The second, an A6M2-21 (Serial V-173), made a forced landing near Tietsan airfield 17 February 1941. The pilot was shot before he could destroy his plane, the fuel system fixed, and it was taken into Chinese service. The plane was extensively flown and studied by a team which included Gerhard Neumann, and a detailed and illustrated report was sent to Washington. Overall they were impressed with the quality of the aircraft, less so by the performance—although this was later put down to using 85 octane fuel rather than the 100 octane required by the Sakae engine.[32]

American opinions

The American military discovered many of the A6M's unique attributes when they recovered a largely intact specimen of an A6M2, the Akutan Zero, on Akutan Island in the Aleutians. During an air raid over Dutch Harbor on 4 June 1942, one A6M fighter was hit by ground-based anti-aircraft fire. Losing oil, Flight Petty Officer Tadayoshi Koga attempted an emergency landing on Akutan Island, about 20 miles (32 km) northeast of Dutch Harbor, but his Zero flipped over on soft ground in a sudden crash-landing. Koga died instantly of head injuries (his neck was broken by the tremendous impact), but his wingmen hoped he had survived and so he went against Japanese doctrine to destroy disabled Zeros.[33] The relatively undamaged fighter was found over a month later by an American salvage team and was shipped to Naval Air Station North Island, where testing flights of the repaired A6M revealed both strengths and deficiencies in design and performance.[30][34]

The experts who evaluated the captured Zero found that the plane weighed about 2,360 kg (5,200 lb) fully loaded, some 1,260 kg (2,780 lb) lighter than the F4F Wildcat, the standard United States Navy fighter of the time. The A6M's airframe was 'built like a fine watch'; the Zero was constructed with flush rivets, and even the guns were flush with the wings. The instrument panel was a 'marvel of simplicity… with no superfluities to distract [the pilot]'. What most impressed the experts was that the Zero's fuselage and wings were constructed in one piece, unlike the American method that built them separately and joined the two parts together. The Japanese method was much slower but resulted in a very strong structure and improved close maneuverability.[30]

American test pilots found that the Zero's controls were 'very light' at 320 km/h (200 mph) but stiffened at speeds above 348 km/h (216 mph) to safeguard against wing failure.[35] The Zero could not keep up with Allied aircraft in high-speed maneuvers, and its low 'never exceed speed' (VNE) made it vulnerable in a dive. Testing also revealed that the Zero could not roll as quickly to the right as it could to the left, which could be exploited.[33] While stable on the ground despite its light weight, the aircraft was designed purely for the attack role, emphasizing long range, maneuverability, and firepower at the expense of protection of its pilot. Most lacked self-sealing tanks and armor plating.[30]

British opinions

Captain Eric Brown, the chief naval test pilot of the Royal Navy, recalled being impressed by the Zero during tests of captured aircraft. 'I don't think I have ever flown a fighter that could match the rate of turn of the Zero. The Zero had ruled the roost totally and was the finest fighter in the world until mid-1943.'[4]

Variants

A6M1, Type 0 Prototypes

The first two A6M1 prototypes were completed in March 1939, powered by the 580 kW (780 hp) Mitsubishi Zuisei 13 engine with a two-blade propeller. It first flew on 1 April, and passed testing within a remarkably short period. By September, it had already been accepted for Navy testing as the A6M1 Type 0 Carrier Fighter, with the only notable change being a switch to a three-bladed propeller to cure a vibration problem.

A6M2a Type 0 Model 11

While the Navy was testing the first two prototypes, they suggested that the third be fitted with the 700 kW (940 hp) Nakajima Sakae 12 engine instead. Mitsubishi had its own engine of this class in the form of the Kinsei, so they were somewhat reluctant to use the Sakae. Nevertheless, when the first A6M2 was completed in January 1940, the Sakae's extra power pushed the performance of the Zero well past the original specifications.

The new version was so promising that the Navy had 15 built and shipped to China before they had completed testing. They arrived in Manchuria in July 1940, and first saw combat over Chongqing in August. There they proved to be completely untouchable by the Polikarpov I-16s and I-153s that had been such a problem for the A5Ms when in service. In one encounter, 13 Zeros shot down 27 I-15s and I-16s in under three minutes without loss. After hearing of these reports, the Navy immediately ordered the A6M2 into production as the Type 0 Carrier Fighter, Model 11. Reports of the Zero's performance slowly filtered back to the US. They were met with scepticism by most US military officials, who thought it impossible for the Japanese to build such an aircraft.

A6M2b Type 0 Model 21

After the delivery of the 65th aircraft, a further change was worked into the production lines, which introduced folding wingtips to allow them to fit on aircraft carriers.[17] The resulting Model 21 would become one of the most produced versions early in the war. A feature was the improved range with 520 L (140 US gal) wing tank and 320 L (85 US gal) drop tank. When the lines switched to updated models, 740 Model 21s had been completed by Mitsubishi, and another 800 by Nakajima. Two other versions of the Model 21 were built in small numbers, the Nakajima-built A6M2-N 'Rufe' floatplane (based on the Model 11 with a slightly modified tail), and the A6M2-K two-seat trainer of which a total of 508 were built by Hitachi and the Sasebo Naval Air Arsenal.[36]

A6M3 Type 0 Model 32

In 1941, Nakajima introduced the Sakae 21 engine, which used a two-speed supercharger for better altitude performance, and increased power to 831 kW (1,130 hp). A prototype Zero with the new engine was first flown on 15 July 1941.[37]

The new Sakae was slightly heavier and somewhat longer due to the larger supercharger, which moved the center of gravity too far forward on the existing airframe. To correct for this, the engine mountings were cut back by 185 mm (7.3 in) to move the engine toward the cockpit. This had the side effect of reducing the size of the main fuselage fuel tank (located between the engine and the cockpit) from 518 L (137 US gal) to 470 L (120 US gal). The cowling was redesigned to enlarge the cowl flaps, revise the oil cooler air intake, and move the carburetor air intake to the upper half of the cowling.[38][39]

The wings were redesigned to reduce span, eliminate the folding tips, and square off the wingtips. The inboard edge of the aileron was moved outboard by one rib, and the wing fuel tanks were enlarged accordingly to 420 L (110 US gal). The two 20 mm wing cannon were upgraded from the Type 99 Mark 1 to the Mark 2,[38] which required a bulge in the sheet metal of the wing below each cannon. The wings also included larger ammunition boxes and thus allowing 100 rounds per cannon.

The Sakae 21 engine and other changes increased maximum speed by only 11 km/h (6.8 mph) compared to the Model 21, but sacrificed nearly 1,000 km (620 miles) of range.[37] Nevertheless, the Navy accepted the type and it entered production in April 1942.[40]

The shorter wingspan led to better roll, and the reduced drag allowed the diving speed to be increased to 670 km/h (415 mph). On the downside, turning and range, which were the strengths of the Model 21, suffered due to smaller ailerons, decreased lift and greater fuel consumption. The shorter range proved a significant limitation during the Solomons Campaign, during which Zeros based at Rabaul had to travel nearly to their maximum range to reach Guadalcanal and return.[41] Consequently, the Model 32 was unsuited to that campaign[40] and was used mainly for shorter range offensive missions and interception.

This variant was flown by only a small number of units, and only 343 were built. One example survives today, and is on display at the Tachiarai Peace Memorial Museum in Tachiarai, Fukuoka.[42]

A6M3 Type 0 Model 22

In order to correct the deficiencies of the Model 32, a new version with folding wingtips and redesigned wing was introduced. The fuel tanks were moved to the outer wings, fuel lines for a 330 L (87 US gal) drop tank were installed under each wing and the internal fuel capacity was increased to 570 L (150 US gal). More importantly, it regained its capabilities for long operating ranges, similar to the previous A6M2 Model 21, which was vastly shortened by the Model 32.

However, before the new design type was accepted formally by the Navy, the A6M3 Model 22 already stood ready for service in December 1942. Approximately 560 aircraft of the new type had been produced in the meantime by Mitsubishi Jukogyo K.K.[43]

According to a theory, the very late production Model 22 might have had wings similar to the shortened, rounded-tip wing of the Model 52.[44] One plane of such arrangement was photographed at Lakunai Airfield ('Rabaul East') in the second half of 1943, and has been published widely in a number of Japanese books. While the engine cowling is the same of previous Model 32 and 22, the theory proposes that the plane is an early production Model 52.[45]

The Model 32, 22, 22 Kō, 52, 52 Kō and 52 Otsu were all powered by the Nakajima Sakae Mod. 21 engine.[41] That engine kept its designation in spite of changes in the exhaust system for the Model 52.

A6M4 Type 0 Model 41/42

Mitsubishi is unable to state with certainty that it ever used the designation 'A6M4' or model numbers for it. However, 'A6M4' does appear in a translation of a captured Japanese memo from a Naval Air Technical Arsenal, titled Quarterly Report on Research Experiments, dated 1 October 1942.[46] It mentions a 'cross-section of the A6M4 intercooler' then being designed. Some researchers believe 'A6M4' was applied to one or two prototype planes fitted with an experimental turbo-supercharged Sakae engine designed for high altitude.[47] Mitsubishi's involvement in the project was probably quite limited or nil; the unmodified Sakae engine was made by Nakajima.[41] The design and testing of the turbo-supercharger was the responsibility of the First Naval Air [Technical] Arsenal (第一海軍航空廠, Dai Ichi Kaigun Kōkūshō) at Yokosuka.[46] At least one photo of a prototype plane exists. It shows a turbo unit mounted in the forward left fuselage.

Lack of suitable alloys for use in the manufacture of a turbo-supercharger and its related ducting caused numerous ruptures, resulting in fires and poor performance. Consequently, further development of a turbo-supercharged A6M was cancelled. The lack of acceptance by the Navy suggests that it did not bestow model number 41 or 42 formally, although it appears that the arsenal did use the designation 'A6M4'. The prototype engines nevertheless provided useful experience for future engine designs.[48]

A6M5 Type 0 Model 52

Sometimes considered as the most effective variant,[49] the Model 52 was developed to again shorten the wings to increase speed and dispense with the folding wing mechanism. In addition, ailerons, aileron trim tab and flaps were revised.[50][51] Produced first by Mitsubishi, most Model 52s were made by Nakajima. The prototype was made in June 1943 by modifying an A6M3 and was first flown in August 1943.[52] The first Model 52 is said in the handling manual[53] to have production number 3904,[54] which apparently refers to the prototype.

Research by Mr. Bunzo Komine published by Mr. Kenji Miyazaki states that aircraft 3904 through 4103 had the same exhaust system and cowl flaps as on the Model 22.[55] This is partially corroborated by two wrecks researched by Mr. Stan Gajda and Mr. L. G. Halls, production number 4007 and 4043, respectively.[56][verification needed][57][verification needed][58][verification needed] (The upper cowling was slightly redesigned from that of the Model 22.[38]) An early production A6M5 Zero with non-separated exhaust, with an A6M3 Model 22 in the background. A new exhaust system provided an increment of thrust by aiming the stacks aft and distributing them around the forward fuselage. The new exhaust system required 'notched' cowl flaps and heat shields just aft of the stacks. (Note, however, that the handling manual translation states that the new style of exhaust commenced with number 3904. Whether this is correct, indicates retrofitting intentions, refers to the prototype but not to all subsequent planes, or is in error, is unclear.) From production number 4274, the wing fuel tanks received carbon dioxide fire extinguishers.[59][60] From number 4354, the radio became the Model 3, aerial Mark 1, and at that point it is said the antenna mast was shortened slightly.[61] Through production number 4550, the lowest exhaust stacks were approximately the same length as those immediately above them. This caused hot exhaust to burn the forward edge of the landing gear doors and heat the tires. Therefore, from number 4551 Mitsubishi began to install shorter bottom stacks.[62] Nakajima manufactured the Model 52 at its Koizumi plant in Gunma Prefecture.[63] The A6M5 had a maximum speed of 565 km/h (351 mph) at 6,000 m (20,000 ft), reaching that altitude in 7:01 minutes.[64]

Subsequent variants included:

A6M5a, Model 52甲 (Kō, 52a) – Starting at Mitsubishi number 4651, an armament change substituted the belt-fed Type 99-2 Mark 4 cannon, with 125 rounds per gun, in place of the drum-fed Type 99-2 Mark 3 cannon that carried 100 rounds per gun. Hence, the bulge in the underside of the wing for each cannon's ammunition drum was deleted and the ejection port for spent cartridge cases was moved. Thicker wing skinning was installed to permit higher diving speeds.[65]

A6M5b, Model 52乙 (Otsu, 52b) – Armament change: The 7.7 mm (.303 in) Type 97 gun (750 m/s (2,500 ft/s) muzzle velocity and 600 m (2,000 ft) range) in the right forward fuselage was replaced by a 13.2 mm Type 3 Browning-derived gun (790 m/s (2,600 ft/s) muzzle velocity and 900 m (3,000 ft) range, with a rate of fire of 800 rounds per minute) with 240 rounds. The larger weapon required an enlarged opening, creating a distinctive asymmetric appearance to the top of the cowling, and a revised gas outlet near the windscreen. In addition, each wing cannon received a fairing at the wing leading edge. A plate of armored glass 45 mm (1.8 in) thick was fitted to the windscreen. A larger propeller spinner was fitted, suggesting a change to the propeller.[66] The type of ventral drop tank was changed, it now had fins and was suspended on a slanted pipe. The first of this variant was completed in April 1944 and it was produced until October 1944.[67]

A6M5c, Model 52丙 (Hei, 52c) – Armament change: One 13.2 mm (.51 in) Type 3 machine gun was added in each wing outboard of the cannon, and the 7.7 mm gun on the left side of the cowling was deleted. Four racks for rockets or small bombs were installed outboard of the 13 mm gun in each wing. Engine change: Some sources state that the hei had a Sakae 31 engine[68] In addition, a 55 mm (2.2 in) thick piece of armored glass was installed at the headrest and an 8 mm (0.31 in) thick plate of armor was installed behind the seat. The mounting of the central 300 L (79 US gal) drop tank changed to a four-post design.[69] Wing skin was thickened further. The first of this variant was completed in September 1944.[65] Because of the gain in weight, this variant was used mainly for intercepting B-29s and special attack.[70]

A6M5-S (A6M5 Yakan Sentōki) – Armament change: To intercept B-29s and other night-flying aircraft, an air arsenal converted some Model 52s to night fighters.[71] They were armed with one 20 mm Type 99 cannon behind the pilot, aimed upward, similar in intent to the Luftwaffe's Schräge Musik installation.[72] However, lack of radar prevented them from being very effective.

Some Model 21 and 52 aircraft were converted to 'bakusen' (fighter-bombers) by mounting a bomb rack and 250 kg (550 lb) bomb in place of the centerline drop tank.

Up to seven Model 52 planes were ostensibly converted into A6M5-K two-seat trainers.[36] Mass production was contemplated by Hitachi, but not undertaken.[73]

A6M6 Type 0 Model 53

The A6M6 was developed to use the Sakae 31a engine, featuring water-methanol engine boost and self-sealing wing tanks.[74][75] During preliminary testing, its performance was considered unsatisfactory due to the additional engine power failing to materialize and the unreliability of the fuel injection system.[76][77] Testing continued on the A6M6 but the end of war stopped further development. Only one prototype was produced.

A6M7 Type 0 Model 62/63

The A6M7 was the last variant to see service. It was designed to meet a requirement by the Navy for a dedicated attack/dive bomber version that could operate from smaller aircraft carriers[9] or according to another source, replace the obsolete Aichi D3A.[78] The A6M7 had considerable design changes compared to previous attempts to make the A6M suitable for dive bombing. This included a reinforced vertical stabilizer, a special bomb rack, provision of two 350-litre drop tanks and fixed bomb/rocket swing stoppers on the underside of the wings.[79][80][81][78][9] It was also given a new powerplant, the Sakae-31 engine, producing 1,130 hp on take-off. The A6M7 had a similar armament layout to the A6M5c with the exception of the bomb centreline bomb rack, capable of carrying 250 kg or 500 kg bombs. Entering production in May 1945,[9][79][81][80] the A6M7 was also used for Kamikaze attacks.[82][83]

A6M8 Type 0 Model 64

Similar to the A6M6 but with the Sakae, now out of production, replaced by the Mitsubishi Kinsei 62 engine with 1,163 kW (1,560 hp), 60% more powerful than the A6M2's engine.[14] This resulted in an extensively modified cowling and nose for the aircraft. The carburetor intake was much larger, a long duct like that on the Nakajima B6N Tenzan was added, and a large spinner — like that on the Yokosuka D4Y Suisei with the Kinsei 62 — was mounted. The armament consisted of two 13.2 mm (.52 in) Type 3 machine guns and two 20 mm (.80 in) Type 99 cannons in the wings. In addition, the Model 64 was modified to carry two 150 L (40 US gal) drop tanks on either wing in order to permit the mounting of a 250 kg (550 lb) bomb on the underside of the fuselage. Two prototypes were completed in April 1945 but the chaotic situation of Japanese industry and the end of the war obstructed the start of the ambitious program of production for 6,300 A6M8s, only the two prototypes being completed and flown.[14][84]

A6M Production: Nagoya, Mitsubishi Jukogyo K.K.

A6M Production: Nagoya, Mitsubishi Jukogyo K.K.[73]

| Year |

Jan. |

Feb. |

Mar. |

Apr. |

May |

June |

July |

Aug. |

Sept. |

Oct. |

Nov. |

Dec. |

Annual |

| 1939 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

1 |

3 |

| 1940 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

3 |

9 |

8 |

9 |

19 |

23 |

19 |

98 |

| 1941 |

23 |

23 |

30 |

27 |

30 |

26 |

25 |

30 |

33 |

43 |

52 |

60 |

402 |

| 1942 |

60 |

58 |

55 |

54 |

58 |

45 |

46 |

51 |

64 |

65 |

67 |

69 |

692 |

| 1943 |

68 |

69 |

73 |

73 |

73 |

73 |

77 |

85 |

93 |

105 |

110 |

130 |

1,029 |

| 1944 |

125 |

115 |

105 |

109 |

95 |

100 |

115 |

135 |

135 |

145 |

115 |

62 |

1,356 |

| 1945 |

35 |

59 |

40 |

37 |

38 |

23 |

15 |

52 |

|

|

|

|

299 |

| Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3,879 |

Production: A6M Production: Ota, Nakajima Hikoki K.K.

Not included: A second A6M1 was completed on 17. March 1939,[74] but was written off without explanation after completing the company's flight test program in July 1940.[75]

A6M Production: Ota, Nakajima Hikoki K.K.[76]

| Year |

Jan. |

Feb. |

Mar. |

Apr. |

May |

June |

July |

Aug. |

Sept. |

Oct. |

Nov. |

Dec. |

Annual |

| 1941 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

6 |

7 |

| 1942 |

19 |

22 |

35 |

31 |

36 |

34 |

52 |

65 |

75 |

88 |

99 |

118 |

674 |

| 1943 |

110 |

119 |

133 |

144 |

148 |

152 |

153 |

156 |

243 |

182 |

202 |

225 |

1,967 |

| 1944 |

238 |

154 |

271 |

230 |

232 |

200 |

163 |

232 |

245 |

194 |

109 |

206 |

2,474 |

| 1945 |

216 |

108 |

207 |

230 |

247 |

185 |

138 |

85 |

|

|

|

|

1,416 |

| Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6,538 |

Trainer

A6M Trainer Production: Chiba, Hitachi Kokuki K.K.[77] and Omura, Dai-Nijuichi K.K.[78]

| Year |

Jan. |

Feb. |

Mar. |

Apr. |

May |

June |

July |

Aug. |

Sept. |

Oct. |

Nov. |

Dec. |

Annual |

| 1943 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

12 |

12 |

15 |

110 |

| 1944 |

12 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

17 |

23 |

30 |

29 |

15 |

23 |

27 |

25 |

252 |

| 1945 |

23 |

8 |

34 |

21 |

31 |

23 |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

155 |

| Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

517 |

According to USSBS Report: 10,934 Figure includes: 10,094 A6M, 323 A6M2-N and 517 A6M-K builds.

According to Francillon: 11,291 Figure includes: 10,449 A6M,[79] 327 A6M2-N,[80] 508 A6M2-K and 7 A6M5-K builds.[35]

Operators

List of Mitsubishi A6M Zero operators

Japan :- Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service

Thailand :- Royal Thai Air Force, Royal Thai Navy

Post-war

Indonesia :- Indonesian Air Force

Republic of China :- Republic of China Air Force

Survivors

Overview

Like many surviving World War II Japanese aircraft, most surviving Zeros are made up of parts from multiple airframes. As a result, some are referred to by conflicting manufacturer serial numbers. Other planes, such as those recovered after decades in a wrecked condition, have been reconstructed to the extent that the majority of their structure is made up of modern parts. All of this means the identities of surviving aircraft can be difficult to confirm. Most flying Zeros have had their engines replaced with similar American units. Only one, the Planes of Fame Air Museum's A6M5, has the original Sakae engine.[95]

The rarity of flyable Zeros accounts for the use of single-seat North American T-6 Texans, with heavily modified fuselages and painted in Japanese markings, as substitutes for Zeros in the films Tora! Tora! Tora!, The Final Countdown, and many other television and film depictions of the aircraft, such as Baa Baa Black Sheep (renamed Black Sheep Squadron). One Model 52 was used during the production of Pearl Harbor.

Australia

840 – on display at the Australian Aviation Heritage Centre in Winnellie, Northern Territory. Wreckage of the forward fuselage, inboard wings, engine, and propeller.[96][97]

5784 – on display at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, Australian Capital Territory. A restored A6M2-21 "V-173" was retrieved as a wreck after the war and later found to have been flown by Saburō Sakai at Lae.[98][99]

China

Unknown serial number – on display at the Beijing Military Museum.[100]

Germany

Replica – on display at the Technik Museum Speyer in Speyer, Rhineland-Palatinate. Replica of the fuselage section on display at IWM London.[101][102]

Indonesia

Unknown serial number – on display at the Dirgantara Mandala Museum in Yogyakarta.[100]

Japan

1493 – on display at the Kawaguchiko Motor Museum in Fujikawaguchiko, Yamanashi.[103]

4168/4240/4241 – on display at the Yūshūkan in Chiyoda, Tokyo.[104]

4685 – on display at Hamamatsu Air Base in Hamamatsu, Shizuoka.[105]

4708 – on display at the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Museum in Komaki, Aichi.[106]

31870 – a two-seater on display at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Taito, Tokyo.[107]

62343 – on display at the Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots in Chiran, Kagoshima.[108]

82729 – on display at the Yamato Museum in Kure, Hiroshima.[109]

91518 – on display at the Kawaguchiko Motor Museum.[110]

92717 – on display at the Kawaguchiko Motor Museum.[111]

Replica – on display at MCAS Iwakuni in Iwakuni, Yamaguchi.[112][113]

Replica – used as movie prop for 2013 film The Eternal Zero. On display at Usa City Peace Museum, Usa, Ōita Prefecture.[114]

New Zealand

3835/3844 – on display at the Auckland War Memorial Museum in Auckland.[115] It was taken to New Zealand from Bougainville in October 1945 on board the ferry Wahine which was being used to repatriate troops. The Zero had been caught on the ground on Bougainville, damaged in the bombing during the Bougainville campaign in November 1943. The plane had been hidden by the Japanese who had restored it with the goal of flying it off the island. The plane was retrieved by RNZAF intelligence officers in September 1945 at the Japanese airfield at Buin in southern Bougainville.[116]

United Kingdom

196 – on display at the Imperial War Museum London in London, Greater London. Forward fuselage displayed.[117][118][119]

3685 – on display at the Imperial War Museum Duxford in Duxford, Cambridgeshire. 3685 was salvaged from Taroa Island in 1991 and acquired by the museum in 2000, before being put on display in 2010. Fuselage displayed in unrestored condition.[120]

United States

1303 – in storage at the Flying Heritage Collection in Everett, Washington.[121]

3618 – in storage at Fantasy of Flight in Polk City, Florida.[122]

4043 – in storage at Fantasy of Flight. Along with several other Zeros, this aircraft was recovered by the Australian War Memorial Museum in the early 1970s from Rabaul in the South Pacific. The markings suggest that it was in service after June 1943 and further investigation suggests that it has cockpit features associated with the Nakajima-built Model 52b. If this is correct, it is most likely one of the 123 aircraft lost by the Japanese during the assault of Rabaul. The aircraft was shipped in pieces to the attraction and was eventually made up for display as a crashed aircraft. Much of the aircraft is usable for patterns, and some of its parts can be restored to one day make this a basis for a flyable aircraft.[123][124]

4340 – on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.[125]

4400 – in storage at the Flying Heritage Collection in Everett, Washington.[126]

5356/5451 – on display at the Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum in Honolulu, Hawaii. This aircraft was formerly flown by the Commemorative Air Force after being restored by Robert Diemert.[127]

5357 – owned by the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino, California. This aircraft, 61-120, is the only airworthy example powered with an original Sakae radial engine.[128]

5450 – on display at the National Naval Aviation Museum at Naval Air Station Pensacola in Pensacola, Florida.[129][130]

23186 – on display at the San Diego Air & Space Museum in San Diego, California. This aircraft is on loan from the National Air and Space Museum.[131][132] The museum previously had another Zero in its collection, msn 4323, but it was destroyed in a fire on 22 February 1978.[133]

51553 – on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio.[134][135] It was restored by Century Aviation.[136]

Replica – owned by Warren Pietsch at the Texas Flying Legends Museum in Houston, Texas. This aircraft, known as the "Blayd" Zero, is a reconstruction based on templating original Zero components recovered from the South Pacific. To be considered a "restoration" and not a reproduction, the builders used a small fraction of parts from the original Zero landing gear in the reconstruction.[137][138] It was built as an A6M2 Model 21.[139][140] This aircraft was damaged in a ground accident on 15 March 2016, when a Goodyear FG-1D Corsair taxiing behind it overran the tail of the Zero, with the Corsair's propeller shredding roughly the last third of the Zero's fuselage and its control surfaces.[141][142]

Replica (3869) – operated by the Southern California Wing of the Commemorative Air Force in Camarillo, California. This aircraft is an A6M3 that was recovered from Babo Airfield, Indonesia, in 1991. It was partially restored from several A6M3s in Russia, then brought to the United States for restoration. The aircraft was re-registered in 1998 and displayed at the Museum of Flying in Santa Monica, California. It uses a Pratt & Whitney R-1830-75 engine.[143][144]

Replica (3852) – owned by the Flying Heritage Collection in Everett, Washington. This aircraft was recovered from Babo Airfield and restored – first in Russia, then in California, and finally in Washington state – before being delivered to the Flying Heritage Collection.[145][146] It has a P&W engine installed.[147]

Replica (3858) – on display at Fagen Fighters WWII Museum in Granite Falls, Minnesota. Formerly owned by Masahide Ishizuka in Kanoya, Kagoshima. Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engine.[148][149][150]

Replica – under airworthy rebuild by Legend Flyers in Everett, Washington[151][152] for the Military Aviation Museum. This aircraft uses a small amount of parts from 3148.[153]

List of Surving Japanese Aircraft

| Museum |

Location |

Description |

Designation |

| USMC Museum |

Quantico (on load Liberal KS) |

Mitsubishi A6M2 (Zeke) |

A6M2 |

| USAF Museum |

Dayton, OH |

A6M2 (under restoration) |

A6M2 |

| Confederate Air Force |

Midland, Tx |

Mitsubishi A6M2 (Zeke) |

A6M2 |

| None |

Unknown location in California |

Mitsubishi A6M2 (Zeke) |

A6M2 |

| Austrailian War Memorial |

Canberra, Austrailia |

Mitsubishi A6M2 (Zeke) |

A6M2 |

| Ueno Park |

Tokyo, Japan |

Mitsubishi A6M2 (in storage) |

A6M2 |

| Museum of Flying |

|

Mitsubishi A6M2 (Zeke) |

A6M2 |

| Lake Kawaguchi Auto Museum |

|

A6M2 |

A6M2 |

| Darwin Aviation Museum |

Darwin, Australia |

A6M2 |

A6M2 |

| National Museum of Naval Aviation |

Pensacola FL |

A6M2 |

A6M2 |

| None |

North Dakota |

A6M2 Zero (new) |

A6M2 |

| Domain War Museum |

Auckland, New Zealand |

A6M3 |

A6M3 |

| Santa Monica Museum of Flying |

Santa Monica, CA |

A6M3 Model 22 |

A6M3 |

| Auckland Museum of Science |

Auckland, NZ |

A6M3 Model 22 |

A6M3 |

| Nagoya Airport Air and Space Museum |

Nagoya, Japan |

A6M3 |

A6M3 |

| Mitsubishi Corporate Headquarters |

|

A6M3 |

A6M3 |

| War Memorial |

Rabaul |

A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| Imperial War Museum |

Duxford, UK |

A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| Military Museum of the People's Revoluti |

Beijing, China |

A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| Air & Space Museum |

Aichi, Japan |

A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| Hamamatsu AB - JASDF Museum |

Hamamatsu, Japan |

A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| Hamamatsu Air Base Collection |

Shizuoka Prefecture |

A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| NASM |

|

A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| Planes of Fame |

Chino, CA |

(2) A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| Bob Diemert |

Manitoba, Canada |

A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| Ueno Park |

Tokyo, Japan |

A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| Yasukuni Shrine |

|

A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| JSDFM Museum |

Hamamatsu City, Japan |

A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| Air Force Museum |

Yogyakarta, Indonesia |

A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| Royal Austrailian Air Force Museum |

Point Cook, Australia |

A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| Weeks Air Museum |

Miami, FL |

A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| Coastwatcher's War Museum |

New Britain, New Guinea |

A6M5 |

A6M5 |

| Imperial War Museum |

London, UK |

A6M5 Cockpit |

A6M5 |

| Mitsubishi KK Komaki Plant Museum |

Nagoya Japan |

A6M5a |

A6M5a |

| Kamikaze Museum |

Kagoshima (Kyushu Island) Japan |

Forward fuselage & wings |

A6M5a |

| San Diego Aero Space Museum |

San Diego, CA |

A6M7 |

A6M7 |

| Kure Marine Museum (2005) |

Kure, Japan |

A6M7 (in storage) |

A6M7 |

| NASM |

Garber |

Nakajima B6N2 "Jill" |

B6N2 |

| NASM |

Garber |

Aichi B7A1 "Grace" |

B7A1 |

| NASM |

Garber |

C6N1-S Myrt |

C6N1 |

| Nimitz Museum |

|

D3A2/3105 w/D3A2/3357 tail |

D3A2 |

| Planes of Fame |

|

D3A2/3178 "Val" |

D3A2 |

| Yasukuni Shrine |

Tokyo, Japan |

D4Y1/4316 "Judy" |

D4Y1 |

| Planes of Fame |

Chino, CA |

D4Y2 "Judy" ex Museum of Flyin |

D4Y2 |

| Iwate High School Education Hall |

|

D4Y4/8003 Aft fuselage & Tail |

D4Y4 |

| JASDF Gifu |

|

E13A1b/61024 miss floats & tai |

E13A1b |

| Kaseda Peace Memorial |

Kagoshima-pref |

E13A1b/41116 Jake |

E13A1b |

| Planes of Fame |

Chino, CA |

G4M1/1280 ex Mus of Flying |

G4M1 |

| Beijing Aviation Museum |

Beijing, China |

G4M2/G4M3 "Betty" |

G4M2 |

| Kawaguchiko Motor Museum |

Yamanashi Prefecture |

G4M2 Aft Fuse only |

G4M2 |

| Nobuo Harada |

Tokyo |

G4M2 |

G4M2 |

| NASM, |

Garber |

G4M3/3401 for fuse & tail only |

G4M3 |

| Museum of Maritime Science |

Tokyo, Japan |

H8K2 "Emily" |

H8K2 |

| NASM |

Garber |

J1N1-S "Irving" |

J1N1 |

| Planes of Fame |

Chino, CA |

J2M3 "Jack" |

J2M3 |

| NASM |

|

J5N1 "Tenrai" |

J5N1 |

| NASM |

Garber |

Kyushu J7W1 "Shinden" |

J7W1 |

| Planes of Fame |

Chino, CA |

J8M1 "Shusui" |

J8M1 |

| Mitsubishi Komaki Plant Museum |

|

J8M1 ex JASDF Gifu |

J8M1 |

| Kawaguchiko Motor Museum |

Yamanashi Prefecture |

K5Y (Willow) |

K5Y |

| Museum Abri Satriamandala |

Jakarta, Indonesia |

K5Y1 |

K5Y1 |

| Kawaguchiko Motor Museum |

|

K5Y1/Replica |

K5Y1 |

| Aerospace Museum |

Cosford, UK |

Ki-100 |

Ki-100 |

| NASM |

Garber |

Ki-115 |

Ki-115 |

| NASM |

Garber |

Ki-115/1002 |

Ki-115 |

| Unknown |

Japan |

Ki-115 (under restoration) |

Ki-115 |

| Tachiarai Peace Memorial |

Fukuoka-pref |

Ki-27 |

Ki-27 |

| Royal Thai Air Force Museum |

Bangkok, Thailand |

Ki-36 "Ida" |

Ki-36 |

| EAA Museum |

Oshkosh, Wi |

Ki-43 |

Ki-43 |

| Col Pay Museum |

Scone, Austrailia |

Ki-43 |

Ki-43 |

| Air Force Museum |

Yogyakarta, Indonesia |

Ki-43 |

Ki-43 |

| Texas Air Factory (new builds) |

Texas |

Ki-43 (new) |

Ki-43 |

| Sold to a museum in the US |

USA (unknown at the moment) |

Ki-43/750 |

Ki-43 |

| Treloar Centre |

Canberra, Australia |

Ki-43 Oscar (incomplete) |

Ki-43 |

| NASM |

Garber |

Kawasaki Ki-45 |

Ki-45 |

| Aerospace Museum |

Cosford, UK |

Ki-46 "Dinah" |

Ki-46 |

| Beijing Army Air Force Museum |

China |

Ki-48 Fuselage only |

Ki-48 |

| Air Force Museum |

Yogyakarta, Indonesia |

Ki-51 "Sonia" |

Ki-51 |

| Treloar Centre |

Canberra, Australia |

Ki-54 "Hickory" (Fuselage only |

Ki-54 |

| Beijing Aerobautical Institute |

Beijing, China |

Ki-54 "Hickory" (Fuselage only |

Ki-54 |

| Peoples Liberation Army Air Force |

Changping, China |

Ki-55 "Ida" |

Ki-55 |

| Weeks Museum |

Miami, FL |

Kawasaki Ki-61 |

Ki-61 |

| Kamikaze Museum |

Chiran, Japan |

Ki-61-II/61017 |

Ki-61 |

| Kawaguchiko Motor Museum |

Yamanashi Prefecture |

Kawasaki Ki-61 |

Ki-61 |

| Museum of Flying |

Santa Monica, CA |

Kawasaki Ki-61 |

Ki-61 |

| Treloar Centre |

Canberra, Australia |

Ki-61 Tony (incomplete) |

Ki-61 |

| Museum Abri Satriamandala |

Jakarta, Indonesia |

Mansyu Ki-79 |

Ki-79 |

| Peace Museum for Kamikaze |

Kyushu, Japan |

Ki-84 |

Ki-84 |

| NASM |

Garber |

Kikka/12 |

Kikka |

| NASM |

Garber |

Kikka/14 center section |

Kikka |

| NASM |

Garber |

M6A1 "Seiran" |

M6A1 |

| Navy Memorial Museum |

Washington DC |

MXY7-K1/5100 Baka |

MXY-7 |

| Yankee Air Corps |

Chino, CA |

Yokosuka MXY-7 Baka |

MXY-7 |

| Indian Air Force Museum |

New Delhi, India |

Yokosuka MXY-7 Baka |

MXY-7 |

| Museum of Science & Industry |

Manchester, UK |

Yokosuka MXY-7 Baka |

MXY-7 |

| Fleet Air Arm Museum |

Yeovilton, UK |

Yokosuka MXY-7 Baka |

MXY-7 |

| Defense Ordanance Disposal School |

Chattenden, UK |

Yokosuka MXY-7 Baka |

MXY-7 |

| Planes of Fame |

Chino, Ca |

Yokosuka MXY-7 Baka |

MXY-7 |

| NASM |

Garber |

Yokosuka MXY-7 Mdl 22 Baka |

MXY-7 |

| USMC Museum |

Quantico |

Yokosuka MXY-7 Baka |

MXY-7 |

| JASDF Iruma |

|

MXY7/1214 w/MXY7/1252 tail |

MXY-7 |

| Yasukuni Shrine |

Tokyo |

MXY7/Replica |

MXY-7 |

| NASM |

Garber |

MXY-7K2 |

MXY-K2 |

| Ohka Memorial Park |

Kashima City, Ibaragi-pref |

MXY7/Replica |

MXY7 |

| USAF Museum |

Dayton, OH |

MXY7-K1 rest as a Ohka 11 |

MXY7 |

| NASM |

Garber |

N1K1 "Rex" |

N1K1 |

| NAS Willow Grove |

|

N1K1 "Rex" |

N1K1 |

| Nimitz Museum |

|

N1K1 "Rex" |

N1K1 |

| NASM |

Champlin |

N1K2-J/5128 "George" |

N1K2-J |

| USAF Museum |

Dayton, OH |

N1K2-J "George" (being fixed) |

N1K2-J |

| New England Air Museum |

Windsor Locks, Conn |

N1K2-J "George" |

N1K2-J |

| Shidenkai Preservation Hall |

Hisho-cho, Ehime-pref |

N1K2-J |

N1K2-J |

| NASM |

Garber |

P1Y1-S/8923 (Francis) |

P1Y1 |

| Tokorozawa Aviation Museum |

|

Type 92 Fighter |

Type91 |

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

-during-the-June-1942-Battle-of-Midway-photo-taken-in-1942-43-80-G-K-13945.jpg)

-during-the-June-1942-Battle-of-Midway-photo-taken-in-1942-43-80-G-K-14025.jpg)

-Battle-of-Midway-5th-May-1942-80-G-64822.jpg)

-Battle-of-Midway-5th-May-1942-80-G-64831.jpg)

-after-she-was-hit-be-a-Kamikaze-of-Samar-Battle-of-Leyte-Gulf-on-25th-Oct-1944-80-G-270516.jpg)

-off-Leyte-25th-Oct-1944-80-G-288881.jpg)

-off-Leyte-25th-Oct-1944-80-G-288882x.jpg)

-Leyte-Gulf-25th-Oct-1944-NH-71524.jpg)

-Kamikaze-attack-25th-Oct-1944-01.jpg)

-during-a-Kamikarze-attack-seen-from-USS-Gambier-Bay-(CVE-73)-during-the-Battle-of-Leyte-Gulf-25th-Oct-1944-ASC2.jpg)