Mitsubishi A6M Zero and its involvement in the Pacific

Introduction

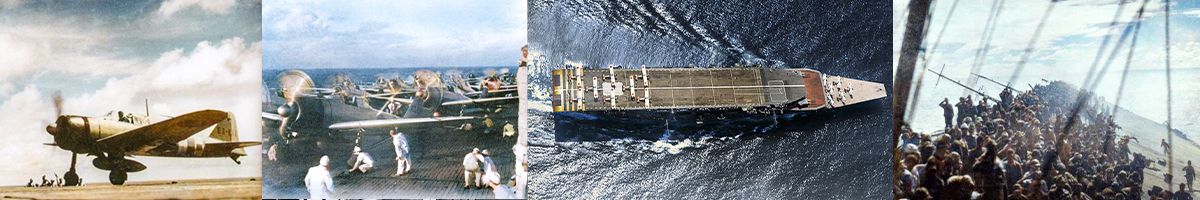

The Mitsubishi A6M Zero, Japan’s premier naval fighter during the early years of World War II, played a dominant role in the Pacific campaign, engaging in intense battles across key strategic locations. As the mainstay of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS), the Zero operated from aircraft carriers and land-based airfields, demonstrating remarkable agility and range that initially overwhelmed Allied opposition. However, as the war progressed, Allied tactics and aircraft advancements eroded the Zero’s early superiority.

Wake Island - December 1941.

Wake Island became an early testing ground for the Mitsubishi A6M Zero’s capabilities in the Pacific. During the initial assault on December 8, 1941, at approximately 1150 hours local time, a formation of 36 Japanese aircraft, including 12 A6M2 Zeros from the carrier Sōryū, attacked Wake Island’s defenses. The Zeros, part of the 12th Kokutai, provided air cover and bombed American defensive positions. These aircraft engaged the US Marine Corps' VMF-211 squadron, which operated 12 F4F-3 Wildcats. The initial attack destroyed eight of the 12 Marine Wildcats on the ground, giving the Japanese air superiority and significantly weakening American air defenses. The bombing also inflicted heavy damage on Wake’s facilities, including fuel depots and barracks, killing at least 23 Marines.

The Japanese invasion force was supported by elements of the 24th Air Flotilla, operating from the carriers Akagi, Kaga, and Hiryū. Other aircraft types used in the attack included D3A1 “Val” dive bombers and B5N2 “Kate” torpedo bombers, which targeted American fortifications and supply depots. The naval invasion was spearheaded by the light cruiser Yubari and destroyers Kisaragi, Hayate, Mutsuki, and Oite, among others. The Japanese suffered unexpected losses when Marine defenders sank Hayate with coastal artillery and destroyed Kisaragi with aerial bombs dropped by Captain Henry Elrod.

Following the initial failure to land troops on December 11, Japanese forces regrouped and launched a second, reinforced invasion fleet on December 23, 1941. This time, additional air support came from the carrier Hōshō, which launched A6M2 Zeros to provide further aerial suppression. The attack began before dawn at approximately 0230 hours, with intense naval bombardment from heavy cruisers Tone and Chikuma, supported by battleships Kongō and Haruna. Japanese troops, primarily from the Maizuru 2nd Special Naval Landing Force, stormed the beaches. The Marine defenders, now critically low on ammunition and supplies, fought valiantly but were eventually overwhelmed. By 0700 hours, Japanese troops had secured most of the island, and the American garrison surrendered shortly after. Wake Island fell, marking one of the first victories in which the Zero demonstrated its dominance in the Pacific. Japanese losses in the campaign included two destroyers (Kisaragi and Hayate), several landing craft, and at least five A6M2 Zeros, while American casualties totaled 120 killed and over 1,100 captured.

Solomon Islands Campaign - 1942-1943

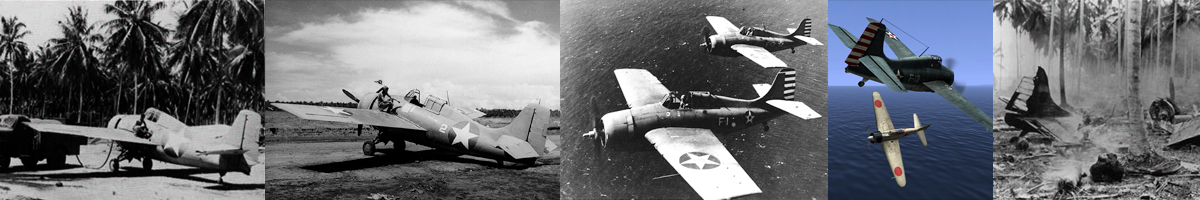

The Solomon Islands campaign saw some of the fiercest aerial engagements of the Pacific War. The Mitsubishi A6M Zero played a crucial role in these battles, engaging US Marine, Navy, and Army Air Forces pilots in prolonged combat. The campaign was centered around Guadalcanal, where Japan sought to maintain control against increasing American counteroffensives.

At the onset of the Guadalcanal campaign in August 1942, the Japanese Navy deployed Zeros from the 204th Kokutai based at Rabaul, as well as elements from the Tainan Air Group. The 252nd Kokutai and 253rd Kokutai also reinforced operations, using forward airfields at Buin and Kahili on Bougainville. These Zeros provided escort for G4M “Betty” bombers conducting strikes on Henderson Field and engaged in daily dogfights against US Marine Corps F4F Wildcats, and later, F4U Corsairs and P-38 Lightnings.

Major battles included the Battle of the Eastern Solomons (August 24, 1942) and the Battle of Santa Cruz Islands (October 26, 1942). During these engagements, Japanese carrier-based Zeros from Shōkaku, Zuikaku, and Zuihō clashed with US Navy fighters, dive bombers, and torpedo bombers. The Japanese lost several experienced pilots, including Lt. Commander Mamoru Seki of Shōkaku’s fighter group. Although the Japanese inflicted significant damage on American ships, they suffered heavy aircraft losses and failed to halt the growing US presence in the region.

During the Cactus Air Force engagements over Guadalcanal, notable aces such as Saburō Sakai, Hiroyoshi Nishizawa, and Toshio Ota fought fiercely against US Marine and Army Air Force pilots. Sakai, already a highly skilled pilot, was severely wounded in a dogfight against SBD Dauntless dive bombers but managed to return to base despite being nearly blinded. Nishizawa, known for his aerobatic skills and high kill count, played a major role in the defense of Rabaul before later being shot down in 1944.

One of the most decisive engagements occurred in November 1943 over Bougainville, where Zeros from the 204th and 582nd Kokutai engaged US Army Air Forces P-38 Lightnings from the 339th Fighter Squadron. In this battle, Major John Mitchell led the famous “Operation Vengeance” mission, intercepting and killing Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of the Pearl Harbor attack. The loss of Yamamoto was a severe blow to Japanese morale and strategic planning in the region.

By early 1944, as attrition and logistical difficulties mounted, the Japanese began to withdraw from Guadalcanal, ceding the island to US forces. The final major air engagements over the Solomons occurred in early 1944, as the Allies launched relentless bombing campaigns against Rabaul, neutralizing the Japanese air presence. By this stage, the Zero was increasingly outmatched by new American fighters, particularly the F6F Hellcat, which outperformed the aging Zero in speed, firepower, and survivability.

Tarawa - November 1943

The Battle of Tarawa (November 20–23, 1943) was the first major amphibious assault in the Central Pacific and a turning point in the island-hopping campaign. As US forces prepared for the invasion, the Imperial Japanese Navy’s 755th Kokutai, operating from the Marshall Islands, attempted to defend Tarawa using A6M2 Zeros, G4M Betty bombers, D3A Val dive bombers, and E13A "Jake" reconnaissance planes. However, the pre-invasion bombing campaign, spearheaded by US carrier-based aircraft and long-range B-24 Liberators from the Seventh Air Force, devastated the Japanese air presence. Over 30 Japanese aircraft were destroyed on the ground, effectively eliminating any aerial opposition before the amphibious assault.

US naval forces, including USS Maryland (BB-46) and USS Tennessee (BB-43), pounded Tarawa’s defenses with 16-inch shells, while cruisers such as USS Indianapolis (CA-35) and USS Portland (CA-33) targeted bunkers and gun emplacements. Despite the relentless bombardment, many Japanese fortifications remained intact, leading to severe US Marine casualties upon landing. The US Navy’s air superiority, led by F6F Hellcats, F4U Corsairs, TBF Avengers, and SB2C Helldivers, ensured that no effective Japanese counterattack materialized. By November 23, 1943, after intense close-quarters fighting, Tarawa was secured, marking a bloody but strategic victory that allowed further advances into the Gilbert and Marshall Islands.

Truk Lagoon - February 1944 (Operation Hailstone)

Truk Lagoon, often referred to as the "Gibraltar of the Pacific," was Japan’s most fortified naval base outside the homeland. Serving as a key stronghold for the IJN’s Combined Fleet, Truk housed numerous warships, submarines, and hundreds of aircraft. In a devastating two-day assault known as Operation Hailstone (February 17–18, 1944), US Task Force 58, under Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher, launched a surprise carrier-based offensive to neutralize this stronghold.

The 201st Kokutai, one of Japan’s elite fighter groups, scrambled A6M5 Zeros, D4Y "Judy" dive bombers, B5N "Kate" torpedo bombers, and G4M Betty bombers to defend Truk. Veteran Japanese aces, including Saburo Sakai and Kaneyoshi Muto, engaged in desperate dogfights against waves of F6F Hellcats, TBF Avengers, and SB2C Helldivers. However, over 250 Japanese aircraft were destroyed, many caught on the ground before they could even take off. The overwhelming numbers and superior performance of US aircraft ensured total dominance in the skies.

Meanwhile, US carrier dive bombers and torpedo bombers systematically dismantled the Japanese fleet. Major IJN warships lost included the cruisers Agano and Naka, which were sunk by bombs and torpedoes, while destroyers, submarines, and numerous support vessels were also annihilated. In total, over 40 Japanese ships were lost, dealing a crippling blow to Japan’s naval capabilities in the Central Pacific. The destruction of Truk’s fleet forced the IJN to relocate remaining assets to safer locations such as Palau and the Philippines, effectively rendering Truk defenseless for the rest of the war.

Palau - March–September 1944

With Truk neutralized, the next target was Palau, an important Japanese defensive outpost. In March 1944, US Task Force 58 launched Operation Desecrate One, a massive air and naval assault designed to weaken Palau’s airfields and harbors. F6F Hellcats, SB2C Helldivers, and TBF Avengers conducted precision strikes, destroying over 150 Japanese aircraft and sinking multiple vessels anchored in the lagoon.

This air campaign paved the way for the Battle of Peleliu (September 15–November 27, 1944), a brutal island battle in which entrenched Japanese forces put up a ferocious defense. The 202nd Kokutai, operating A6M5 Zeros, attempted to challenge American air dominance but suffered heavy losses to carrier-based Hellcats. Though the air war was quickly won, US Marines and Army troops faced a costly ground battle, enduring one of the highest casualty rates of the entire Pacific campaign. The seizure of Peleliu and its airfield allowed the US to support future operations in the Philippines and Mariana Islands.

Guam - July–August 1944

During the Battle of Guam (July 21–August 10, 1944), US forces sought to retake the island, which had been captured by Japan in 1941. Preceding the invasion, B-24 Liberators from the Seventh Air Force and carrier-based aircraft from Task Force 58 bombarded Japanese defenses. The 343rd Kokutai, one of Japan’s premier fighter units, deployed A6M5 Zeros, Ki-44 "Tojo" fighters, and Ki-67 "Peggy" bombers in an attempt to resist the American onslaught. However, US Hellcats and Corsairs dominated the skies, destroying over 100 Japanese aircraft.

US Navy battleships and cruisers, including USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) and USS Tennessee (BB-43), shelled Japanese positions, paving the way for the amphibious landings. Despite fierce jungle warfare, US forces secured Guam by August 10, 1944. The island’s recapture was crucial, as it allowed the US to construct B-29 airfields for direct bombing raids on Japan.

Saipan - June–July 1944

Saipan was one of the most critical objectives of the Marianas campaign, as its capture would bring Tokyo within range of B-29 bombers. The Battle of Saipan (June 15–July 9, 1944) was preceded by the largest carrier battle of the Pacific War: the Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 19–20, 1944), known as the "Great Marianas Turkey Shoot."

In a desperate attempt to stop the US advance, Japan’s 1st Air Fleet launched hundreds of aircraft, including A6M5 Zeros, D4Y "Judy" dive bombers, and B6N "Jill" torpedo bombers. However, US F6F Hellcats, operating from Task Force 58’s carriers, shot down over 300 Japanese aircraft with minimal losses. The destruction of Japan’s carrier air power was compounded by the sinking of three aircraft carriers: Shokaku, Taiho, and Hiyo.

With US air superiority established, carrier-based bombers and land-based B-24 Liberators pounded Saipan’s airfields, bunkers, and artillery positions. Naval bombardments from USS New Mexico (BB-40), USS California (BB-44), and USS Tennessee (BB-43) helped clear the way for landings. On the ground, Japanese forces fought to the death, with over 30,000 defenders killed in brutal urban and jungle combat. Mass civilian suicides at Marpi Point marked the tragic end of the battle.

By July 9, 1944, Saipan was secured, leading to the fall of Prime Minister Hideki Tojo’s government and the beginning of US strategic bombing raids on Japan.

Key Pilots and Aces

Throughout these campaigns, the Mitsubishi A6M Zero was flown by some of Japan’s most skilled aces. Saburō Sakai, a legendary pilot, scored numerous victories in the Solomons, including engagements over Guadalcanal. Hiroyoshi Nishizawa, known as the “Devil of Rabaul,” was another leading ace, excelling in the same region before being killed later in the war. Tetsuzō Iwamoto, one of the highest-scoring aces in the IJN, fought in the Solomons and later defended Japan against B-29 raids. Other notable pilots included Toshio Ota, Tomokazu Kasai, and Shigeru Itaya, who led the first wave of Zeros at Pearl Harbor.

By the latter half of the war, the Zero’s early dominance had waned due to superior American aircraft such as the F6F Hellcat and the P-38 Lightning, combined with improved Allied tactics and overwhelming numerical superiority. Despite its shortcomings in the face of advancing technology, the Zero remained in frontline service until the war’s end, including its final role as the primary aircraft for kamikaze missions. The aircraft’s impact on the Pacific War remains one of both early brilliance and eventual obsolescence, reflecting the broader trajectory of Japan’s wartime fortunes.

Japanese Kamikaze Attacks in World War II (1944–1945)

The Rise of Kamikaze – Japan’s Desperate Counteroffensive (1944–1945)

By late 1944, Japan’s air and naval forces were critically weakened. The loss of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam in July–August 1944 gave the United States airfields within striking distance of Japan, enabling the devastating B-29 strategic bombing campaign. With its conventional forces unable to stop the U.S. advance, Japan turned to a desperate tactic: Kamikaze attacks. The first organized Kamikaze units were formed in October 1944 under Vice Admiral Takijirō Ōnishi, who commanded the 1st Air Fleet in the Philippines. By war’s end, Japan would sacrifice over 3,800 Kamikaze pilots, primarily from the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS) and Imperial Japanese Army Air Service (IJAAS), to inflict damage on U.S. Navy warships. The U.S. countered with naval and submarine tactics, while Japan’s naval strategy adapted to maximize Kamikaze effectiveness, peaking during the Okinawa campaign.

Battle of Saipan (15th June 1944 – 9th July 1944)

The U.S. invasion of Saipan aimed to secure a B-29 base, overwhelming Japan’s defenses with air units like VF-31 (USS Cabot – CVL-28) with F6F Hellcats led by Lt. Cecil E. Harris (24 kills), VF-10 (USS Enterprise – CV-6) with Lt. Alexander Vraciu (19 kills), and VMSB-231 (USS Bunker Hill – CV-17) with SB2C Helldivers. Japan’s 121st Kokutai (IJNAS, Saipan) flew A6M5 Zeros and D3A Vals, with some pilots executing early suicide dives as losses mounted. U.S. naval tactics relied on fighter sweeps, while USS Flying Fish (SS-229) sank two supply ships on 20th June, disrupting air operations. Japan lost 350+ aircraft; the U.S. lost 120.

U.S. Navy Ships Hit:

USS Bunker Hill (CV-17) after a near miss by Japanese air attack 19th June 1944

USS Bunker Hill (CV-17) – 19th June 1944:

Captain: George L. Dyer

Damage: D4Y Judy crashed at 08:45 AM, igniting fuel lines.

Casualties: 18 killed, 32 wounded.

Aircraft Losses: 10 F6F Hellcats damaged/destroyed.Battle of Guam (21st July 1944 – 10th August 1944)

Guam’s fall completed the Mariana Islands’ loss, exposing Japan further. The 755th Kokutai (IJNAS, Guam) deployed G4M Betty bombers, with several pilots resorting to suicide runs after conventional strikes failed. U.S. carriers VF-10 and VF-31 (USS Enterprise and Cabot) countered with F6F Hellcats. U.S. naval tactics emphasized CAP at 10,000 feet, while USS Stingray (SS-186) sank a troop transport on 25th July, limiting pilot reinforcements. Japan lost 200+ aircraft; the U.S. lost 80.

U.S. Navy Ships Hit:

USS Indianapolis (CA-35) – 22nd July 1944:

Captain: Charles B. McVay III

Damage: A6M Zero grazed hull at 11:20 AM, minimal structural impact.

Casualties: 6 killed, 20 wounded.Battle of Peleliu (15th September 1944 – 27th November 1944)

Peleliu’s airfield was vital for the Philippines campaign, but Japan’s 302nd Kokutai (IJNAS, Peleliu) turned to suicide tactics with A6M5 Zeros and Ki-43 Oscars as air defenses crumbled. U.S. units VF-19 (USS Lexington – CV-16) with F6F Hellcats and VMSB-341 (USS Franklin – CV-13) with SB2C Helldivers provided air support. U.S. naval tactics used layered AA fire (5-inch at 10,000 yards, 40mm at 3,000), while USS Nautilus (SS-168) sank a supply ship on 18th September, cutting munitions. Japan lost 200+ aircraft; the U.S. lost 85.

U.S. Navy Ships Hit:

USS Franklin (CV 13) viewed from USS Hornet (CV 12) operating near the Marianas 1st Aug 1944

USS Franklin (CV-13) – 15th October 1944:

Captain: Leslie E. Gehres

Damage: Ki-51 Sonia hit at 13:10 PM, sparking fuel fires.

Casualties: 56 killed, 100+ wounded.

Aircraft Losses: 20 aircraft destroyed.Battle of Leyte Gulf (23rd–26th October 1944) – The First Kamikaze Attacks

The U.S. Sixth Army landed on Leyte on 20th October 1944, prompting Japan’s multi-pronged naval counterattack. As it faltered, Vice Admiral Ōnishi ordered the first organized Kamikaze attacks on 25th October with the Shikishima Unit. U.S. air units—VF-15 (USS Essex – CV-9) with Cmdr. David McCampbell (34 kills), VF-27 (USS Princeton – CVL-23) with Lt. James Shirley, and VT-19 (USS Lexington – CV-16) with TBM Avengers—faced the 201st Kokutai (Clark Field) and 701st Air Group (Cebu) with A6M5 Zeros, Ki-43 Oscars, and Ki-51 Sonias. U.S. naval tactics introduced radar pickets (e.g., USS Johnston), while USS Darter (SS-227) sank cruiser Atago on 23rd October, disrupting command. Japan lost ~500 aircraft (40 Kamikazes); the U.S. lost ~120.

USS Franklin (CV-13) and USS Belleau Wood (CVL 24) both hit by a Japanese Kamikazes operating off Philippines 30th Oct 1945

On 30th October 1944, the USS Franklin (CV-13), an Essex-class aircraft carrier, and USS Belleau Wood (CVL-24), an Independence-class light carrier, were operating as part of Task Group 38.4 (TG 38.4) under Rear Adm. Ralph E. Davison, approximately 1,000 miles east of Samar in the Philippine Sea. This was shortly after the Battle of Leyte Gulf (23rd–26th October 1944), where U.S. forces supported the Leyte landings that began on 20th October. The task group, including Franklin, Belleau Wood, USS Enterprise (CV-6), and USS San Jacinto (CVL-30), was conducting air strikes against Japanese airfields and shipping around Manila to interdict reinforcements, following their success in sinking the super-battleship Musashi on 24th October during the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea. Around 14:00 local time, a group of five Japanese Kamikaze aircraft—identified as Mitsubishi A6M Zeros from the IJNAS—approached TG 38.4 at high altitude (approximately 18,000 feet), exploiting gaps in the U.S. Combat Air Patrol (CAP) of F6F Hellcats from VF-15 (Franklin) and VF-21 (Belleau Wood). Despite efforts by shipboard anti-aircraft guns, which splashed three of the attackers, two planes broke through.

The USS Franklin was struck first at approximately 14:26. A Zero, carrying a 551-pound (250 kg) general-purpose bomb, crashed into the flight deck at frame 127, slightly starboard of the centerline, at a 20-degree angle. The aircraft penetrated to the gallery deck below, where its bomb detonated, blowing a 30-by-35-foot hole in the flight deck and igniting fires that spread to the hangar deck between frames 110 and 150. The explosion killed 56 crewmen instantly and wounded 60 others, with fires fueled by 11 armed and fueled aircraft on the hangar deck, including F6F Hellcats and TBM Avengers from Air Group 13 (CVG-13). At the time, only five of Franklin’s eight repair parties had set Condition ABLE (full readiness), with Repair I (hangar) notably delayed, exacerbating the damage. Crew efforts extinguished the flight deck fire by 15:30 and the hangar deck blaze by 16:25, though smoldering fires persisted below decks until 18:00. Total casualties rose to 64 killed and over 60 wounded as secondary fires took hold. Moments later, at 14:27, the fifth Zero—after dropping a bomb that exploded harmlessly 30 feet off Franklin’s starboard side abreast frame 60—veered toward Belleau Wood and crashed into its flight deck aft, among 11 fully loaded F6F Hellcats from VF-21. The impact sparked multiple explosions and severe fires, holing the deck and killing 92 crewmen while wounding 97 others, including 54 seriously. Damage control teams battled the blaze for three hours, finally containing it by 17:30, though the flight deck remained compromised.

Both carriers were heavily damaged but survived due to heroic damage control efforts. Franklin’s crew patched the flight deck within 76 minutes to recover aircraft, while Belleau Wood’s team moved undamaged TBM Avengers away from the flames to prevent further explosions. The attack occurred amidst a broader Japanese response to their worsening position in the Philippines, following the Leyte Gulf defeat, with Kamikaze tactics escalating under Vice Adm. Takijirō Ōnishi’s First Air Fleet. U.S. naval defenses included radar pickets and AA fire from 5-inch/38-caliber guns, 40mm Bofors, and 20mm Oerlikons, though the high-altitude approach and speed (over 300 knots) of the Zeros overwhelmed initial defenses. Franklin’s gunners downed a third Zero targeting USS Enterprise, preventing further damage to TG 38.4. Post-attack, both ships retired to Ulithi Atoll in the Caroline Islands for temporary repairs—Franklin arriving by 3rd November under her own power at 14 knots, and Belleau Wood between 3rd and 10th November after minor fixes by its crew. Franklin then proceeded to Puget Sound Navy Yard in Bremerton, Washington, arriving 28th November for extensive repairs, completed by 2nd February 1945, while Belleau Wood reached Hunters Point, San Francisco, on 29th November via Pearl Harbor, undergoing a six-week overhaul with added 40mm guns, rejoining combat by mid-January 1945.

U.S. Navy Ships Hit:

USS ST Lo (CVE 63) after she was hit be a Kamikaze of Samar Battle of Leyte Gulf on 25th Oct 1944

USS St. Lo (CVE-63) – 25th October 1944:

Captain: Francis J. McKenna

Damage: A6M5 Zero hit at 10:51 AM, sinking ship in 30 minutes.

Casualties: 114 killed, 250+ wounded.

Aircraft Losses: 28 F6F Hellcats and TBM Avengers destroyed.

USS Suwannee (CVE 27) after a 250kg bomb hit the flight and hangar decks 25th Oct 1944

USS Suwannee (CVE-27) – 25th October 1944:

Captain: Joseph J. Clark

Damage: Two D3A Vals struck at 12:40 PM and 12:45 PM, causing fires.

Casualties: 107 killed, 160+ wounded.

Aircraft Losses: 25 aircraft destroyed.USS Kalinin Bay (CVE-68) – 25th October 1944:

Captain: T. B. Williamson

Damage: Multiple A6M Zeros hit between 10:50 AM and 11:00 AM, heavily damaged.

Casualties: 5 killed, 55 wounded.

Aircraft Losses: 10 aircraft damaged.

USS Santee (CVE 29) Kamikaze attack 25th Oct 1944

USS Santee (CVE-29) – 25th October 1944:

Captain: William D. Sample

Damage: A6M Zero hit at 7:40 AM, plus a torpedo strike.

Casualties: 16 killed, 27 wounded.

A damaged dive bomber plunges into USS Kitkun Bay. Photo description: The USS Kitkun Bay (CVE-71) during a Kamikarze attack seen from USS Gambier Bay (CVE-73) during the Battle of Leyte Gulf 25th Oct 1944

USS Kitkun Bay (CVE-71) – 25th October 1944:

Captain: John P. Whitney

Damage: A6M Zero hit at 11:20 AM, damaging deck.

Casualties: 10 killed, 25 wounded.Luzon and Lingayen Gulf (January 1945) – Kamikaze Hell

The U.S. targeted Luzon for airfields, landing at Lingayen Gulf on 9th January 1945, facing intensified Kamikaze assaults from the 201st and 701st Kokutai (Luzon and Manila) with A6M5 Zeros and D4Y Judys. VF-3 (USS Yorktown – CV-10) and VT-80 (USS Ticonderoga – CV-14) provided air defense. U.S. naval tactics expanded CAPs to 48 fighters per carrier, while USS Barb (SS-220) sank three supply ships off Luzon on 5th January, starving Kamikaze bases. Japan lost 150+ aircraft (60 Kamikazes); the U.S. lost 70, but landed 175,000 troops by late January.

U.S. Navy Ships Hit:

USS Ommaney Bay (CVE-79) – 4th January 1945:

Captain: Howard L. Young

Damage: Ki-51 Sonia hit at 5:00 PM, sinking ship.

Casualties: 93 killed, 65 wounded.USS Columbia (CL-56) – 6th January 1945:

Captain: Maurice E. Curts

Damage: Two A6M Zeros impacted at 1:30 PM and 1:45 PM, causing severe fires.

Casualties: 24 killed, 80 wounded.USS Louisville (CA-28) – 6th January 1945:

Captain: Rufus E. Rose

Damage: D4Y Judy hit at 9:20 AM, damaging bridge and turrets.

Casualties: 36 killed, 90 wounded.USS New Mexico (BB-40) – 6th January 1945:

Captain: Robert W. Fleming

Damage: A6M Zero hit at 12:15 PM, striking bridge.

Casualties: 31 killed, 87 wounded.Battle of Iwo Jima (19th February 1945 – 26th March 1945)

Iwo Jima’s airfields were critical for B-29 support, prompting the 252nd Kokutai (IJNAS, Iwo Jima) to launch Kamikaze Zeros. U.S. units VF-9 (USS Yorktown – CV-10) and VT-83 (USS Essex – CV-9) countered with Hellcats and Avengers. U.S. naval tactics employed night CAPs with F6F-5Ns, while USS Spadefish (SS-411) sank a troop transport on 20th February, reducing pilot numbers. Japan lost 250+ aircraft; the U.S. lost 120.

U.S. Navy Ships Hit:

USS Saratoga (CV-3) forward flight deck on fire hit by several Kamikazes off Iwo Jima 21st Feb 1945

USS Saratoga (CV-3) – 21st February 1945:

Captain: James H. Crommelin

Damage: Two A6M Zeros struck at 5:00 PM and 5:05 PM, igniting fuel and aircraft.

Casualties: 123 killed, 192 wounded.

Aircraft Losses: 36 aircraft destroyed.Battle of Okinawa (1st April 1945 – 22nd June 1945) – Largest Kamikaze Assault and Kikusui Operations

Okinawa, 340 miles from Japan, was the final major stand before an anticipated homeland invasion, with the U.S. Tenth Army landing on 1st April, supported by Task Force 58 and Task Force 57. Japan unleashed the Kikusui operations—10 mass Kamikaze waves from 6th April to 22nd June—deploying over 1,500 aircraft from the 721st Kokutai (Kyushu) with Ki-84 Franks, Ki-27 Nates, and A6M5 Zeros, the Kikusui Corps with G4M Bettys and D4Y Judys, and the 343rd Kokutai’s elite Ki-61 Hiens. U.S. air units—VF-17 (USS Hornet – CV-12), VBF-83 (USS Essex – CV-9), and VT-9 (USS Yorktown – CV-10)—faced the onslaught, with Kikusui waves peaking at 355 planes on 6th April (Kikusui I), 165 on 16th April (Kikusui II), and 230 on 11th May (Kikusui VI), using “bait” Bettys to lure fighters, followed by low-flying Zeros skimming waves to evade radar. Japan lost 1,500+ aircraft; the U.S. lost 763, but landed 82,000 troops by mid-April, overcoming the sinking of 36 ships and damage to 368.

The Battle of Okinawa, spanning 1st April to 22nd June 1945, marked Japan’s final major stand against the advancing Allies, just 340 miles from its homeland, as the U.S. sought a staging ground for a potential invasion. The U.S. Tenth Army, under Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr., landed on Okinawa’s western beaches on 1st April, supported by the massive Task Force 58 (fast carriers under Vice Adm. Marc Mitscher) and Task Force 57 (British carriers under Vice Adm. Sir Bernard Rawlings), deploying over 1,300 ships, including 18 carriers, 10 battleships, and 200 destroyers. Japan, facing imminent defeat, unleashed its most intense Kamikaze campaign—the Kikusui (Floating Chrysanthemums) operations—comprising 10 mass suicide waves from 6th April to 22nd June, totaling over 1,500 aircraft from the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS) and Imperial Japanese Army Air Service (IJAAS).

The 721st Kokutai, based in Kyushu, flew advanced Ki-84 Franks, aging Ki-27 Nates, and A6M5 Zeros armed with 550-pound bombs, while the Kikusui Special Attack Corps deployed G4M Betty bombers and D4Y Judy dive bombers, supplemented by the elite 343rd Kokutai’s Ki-61 Hien fighters from Kanoya. Japan’s strategy, led by Combined Fleet Commander Adm. Soemu Toyoda, aimed to cripple the U.S. fleet and force a negotiated peace, peaking with waves like Kikusui I (6th April, 355 planes), Kikusui II (16th April, 165 planes), and Kikusui VI (11th May, 230 planes), using “bait” G4M Bettys flying high to lure U.S. fighters, followed by low-flying Zeros and Judys skimming waves at 50 feet to evade radar detection. U.S. carrier air units—VF-17 (USS Hornet – CV-12) with F6F Hellcats, VBF-83 (USS Essex – CV-9) with F4U Corsairs, and VT-9 (USS Yorktown – CV-10) with TBM Avengers—mounted fierce resistance, supported by aces like Lt. Cmdr. Roger Hedrick (VBF-83), who downed multiple Kamikazes.

The U.S. fleet faced devastating strikes, with key incidents including: USS Franklin (CV-13) on 19th March (pre-Okinawa escort, Capt. Leslie E. Gehres), hit by two D4Y Judys at 7:08 AM, killing 807 and wounding 487 with 32 aircraft lost in the war’s worst carrier toll;

USS Newcomb (DD-586) on 6th April (Kikusui I, Capt. Lawrence B. Cook), struck by four A6M Zeros between 5:45 PM and 6:00 PM, killing 40 and wounding 25, nearly sinking; USS Kidd (DD-661) on 11th April (Kikusui II, Capt. Allan Roby), hit by an A6M Zero at 1:40 PM into the bridge, killing 38 and wounding 55; USS Intrepid (CV-11) on 16th April (Kikusui II, Capt. Giles E. Short), struck by an A6M Zero at 1:36 PM, killing 10, wounding 87, and destroying 15 aircraft; USS Laffey (DD-724) on 16th April (Kikusui II, Capt. Frederick J. Becton), enduring 5 Kamikazes (A6M Zeros, D3A Vals) and 4 bombs from 8:30–9:00 AM yet surviving with 32 killed and 71 wounded due to gunnery and fighter support; USS Bunker Hill (CV-17) on 11th May (Kikusui VI, Capt. George L. Dyer), hit by two A6M Zeros at 10:05 AM and 10:07 AM, penetrating the deck and igniting 52 aircraft below, killing 393 and wounding 264; and USS Enterprise (CV-6) on 14th May (Kikusui VI, Capt. Grover B. H. Hall), struck by a D4Y Judy at 6:55 AM through the flight deck, killing 15, wounding 30, and destroying 14 aircraft.

Additional notable hits included USS Maryland (BB-46) on 7th April (Capt. John E. Meyer), struck during Operation Ten-Go with 35 killed, and USS Hancock (CV-19) on 7th April (Capt. Robert F. Hickey), hit by an A6M Zero at 12:20 PM, killing 62 and wounding 71 with 20 aircraft lost. Japan’s naval strategy peaked with Operation Ten-Go on 7th April, deploying battleship Yamato—carrying only enough fuel for a one-way trip—as a sacrificial lure under Vice Adm. Seiichi Ito, escorted by cruiser Yahagi and eight destroyers; Yamato drew 386 U.S. aircraft, sinking at 2:23 PM with 2,498 crew lost, enabling 150 Kamikazes to strike simultaneously.

U.S. naval tactics countered with radar picket stations (16 stations, 50–100 miles out) using SCR-584 radar to detect 80% of attackers, though 15 destroyers sank by May; CAPs of 48–72 fighters per carrier group, with “Jack Patrols” at 1,000 feet, intercepted 60% (e.g., VF-17 downed 200+); and AA fire from 5-inch/38-caliber guns, 40mm Bofors, and 20mm Oerlikons downed 30–40% of penetrators (e.g., Laffey’s 16 guns).

Submarines like USS Trigger (SS-237) sank two freighters off Kyushu on 10th April, and USS Nautilus spotted Kanoya airfield on 8th April, guiding strikes that destroyed 50+ planes, disrupting Kikusui logistics. Japan lost 1,500+ aircraft, mostly Kamikazes, while the U.S. lost 763 to combat, strikes, and operational causes, yet landed 82,000 troops by mid-April despite 36 ships sunk and 368 damaged, showcasing resilience against Japan’s fiercest aerial onslaught.

U.S. Navy Ships Hit (Selected Major Incidents):

USS Franklin (CV 13) hit by bombs from a Japanese aircraft viewed from USS Santa Fe (CL 60) 19th Mar 1945

USS Franklin (CV-13) – 19th March 1945 (Pre-Okinawa Escort):

Captain: Leslie E. Gehres

Damage: Two D4Y Judys hit at 7:08 AM, pre-empting Okinawa, causing massive fires.

Casualties: 807 killed, 487 wounded (worst carrier toll of the war).

Aircraft Losses: 32 aircraft destroyed.USS Newcomb (DD-586) – 6th April 1945 (Kikusui I):

Captain: Lawrence B. Cook

Damage: Four A6M Zeros hit between 5:45 PM and 6:00 PM, nearly sinking ship.

Casualties: 40 killed, 25 wounded.USS Kidd (DD-661) – 11th April 1945 (Kikusui II):

Captain: Allan Roby

Damage: A6M Zero hit at 1:40 PM, striking bridge and engine room.

Casualties: 38 killed, 55 wounded.USS Intrepid (CV-11) – 16th April 1945 (Kikusui II):

Captain: Giles E. Short

Damage: A6M Zero hit at 1:36 PM, damaging deck and hangar.

Casualties: 10 killed, 87 wounded.

Aircraft Losses: 15 aircraft destroyed.USS Laffey (DD-724) – 16th April 1945 (Kikusui II):

Captain: Frederick J. Becton

Damage: Hit by 5 Kamikazes (A6M Zeros, D3A Vals) and 4 bombs between 8:30 AM and 9:00 AM; survived due to gunnery and fighter support.

Casualties: 32 killed, 71 wounded.

USS Bunker Hill (CV-17) after being hit by Kamikaze planes during the Okinawa operation 11th May 1945

USS Bunker Hill (CV-17) – 11th May 1945 (Kikusui VI):

Captain: George L. Dyer

Damage: Two A6M Zeros hit at 10:05 AM and 10:07 AM, penetrating deck, igniting 52 aircraft below.

Casualties: 393 killed, 264 wounded.

Aircraft Losses: 52 aircraft destroyed.

USS Enterprise (CV-6) burning after a kamikaze attack during the battle of Okinawa 14th May 1945

USS Enterprise (CV-6) – 14th May 1945 (Kikusui VI):

Captain: Grover B. H. Hall

Damage: D4Y Judy hit at 6:55 AM, punching through flight deck into hangar.

Casualties: 15 killed, 30 wounded.

Aircraft Losses: 14 aircraft destroyed.Land Battle of Okinawa (1st April 1945 – 22nd June 1945)

The land battle of Okinawa began on 1st April 1945 when the U.S. Tenth Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr., landed unopposed on the Hagushi beaches of western Okinawa at 8:30 AM. This force, eventually totaling over 183,000 troops, included the XXIV Corps under Maj. Gen. John R. Hodge, with the 7th, 27th, 77th, and 96th Infantry Divisions, and the III Amphibious Corps under Maj. Gen. Roy S. Geiger, with the 1st, 2nd, and 6th Marine Divisions.

They faced Japan’s 32nd Army, led by Lt. Gen. Mitsuru Ushijima, numbering around 76,000 troops, down from 100,000 after redeployments to Formosa, and bolstered by 20,000–40,000 Okinawan conscripts known as Boeitai.

The U.S. landing was supported by Task Force 51, under Vice Adm. Richmond Kelly Turner, with over 1,300 ships, including 18 carriers and 10 battleships. Japan opted not to contest the beaches, instead fortifying the inland Shuri Line, a 10-mile defensive network of ridges, caves, and bunkers across southern Okinawa, designed by Ushijima’s chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Isamu Cho, and Col. Hiromichi Yahara. In the north, the 6th Marine Division, led by Maj. Gen. Lemuel C. Shepherd Jr., advanced rapidly, engaging the Japanese on the Motobu Peninsula from 13th April.

They captured the Yae-Take stronghold by 18th April after intense fighting, killing 2,500 Japanese and taking 2,000 prisoners, at a cost of 236 U.S. killed and 1,061 wounded. The north was secured by 20th April with little further resistance.

In contrast, the southern campaign turned brutal as XXIV Corps moved on 4th April, hitting the outer Shuri defenses at Kakazu Ridge, defended by the 62nd Division under Lt. Gen. Takeo Fujioka with 75mm guns, mortars, and machine-gun nests.

The U.S. 7th and 96th Divisions attacked Kakazu on 9th April, losing 1,500 men in two days to interlocking fire and counterattacks, forcing a retreat by 11th April. A second assault on 19th April, with 24 battalions from the 27th, 77th, and 96th Divisions and 324 artillery pieces firing 19,000 shells, broke through using flamethrowing M4 Shermans and satchel charges, but cost 720 U.S. lives.

The Shuri Line’s heart, anchored by Shuri Castle, held through May, with Japan’s 44th Independent Mixed Brigade and 24th Division under Lt. Gen. Tatsumi Amamiya using reverse-slope defenses, tunnels, and coral caves. The U.S. countered with “blowtorch and corkscrew” tactics—flamethrowers, napalm, and explosives—backed by 650 Navy and Marine aircraft and 27 artillery battalions delivering 157,000 tons of shells by June.

Torrential rain from mid-May turned the terrain into a muddy quagmire, stalling tanks and troops as the 1st and 6th Marines joined XXIV Corps to encircle Shuri. On 29th May, the 77th Division seized Shuri Castle after the 32nd Army withdrew south to the Kiyan Peninsula on Yahara’s orders, overriding Cho’s push for a counterattack.

The final phase, from 1st to 22nd June, saw Ushijima’s forces retreat to three pockets—Mabuni, Kunishi Ridge, and Hill 95—where the 62nd and 24th Divisions fought from caves and pillboxes.

Kunishi Ridge fell to the 1st Marines on 17th June after five days of close combat, killing 4,000 Japanese at a cost of 1,000 U.S. casualties. Ushijima, Cho, and their staff committed seppuku in Mabuni on 22nd June at 4:00 AM as U.S. forces closed in, ending organized resistance. U.S. casualties reached 12,520 killed—4,907 Army, 4,675 Marines, 2,938 Navy—36,631 wounded, and 34 missing.

Japanese losses ranged from 66,000 to 110,000 troops, with 7,400 captured, alongside 42,000 to 150,000 civilian deaths from artillery, starvation, or coerced suicides due to Japanese propaganda. Buckner was killed by artillery shrapnel on 18th June, succeeded by Geiger and later Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell. The battle secured Okinawa as a base for 548,000 troops by July, but its staggering cost influenced the U.S. decision to use atomic bombs rather than invade Japan’s mainland.

U.S. Naval Tactics Against Kamikaze Attacks

The Kamikaze threat, peaking at Okinawa, forced rapid U.S. naval adaptation. Radar picket stations (16 stations, 50–100 miles out) with destroyers like USS Laffey used SCR-584 radar to detect 80% of attackers, though 15 sank by May. CAPs of 48–72 F6F Hellcats and F4U Corsairs per carrier group, with “Jack Patrols” at 1,000 feet, intercepted 60% (e.g., VF-17 downed 200+ by June). AA fire coordination—5-inch/38-caliber guns, 40mm Bofors, and 20mm Oerlikons—downed 30–40% of penetrators (e.g., Laffey’s 16 guns on 16th April). Fleet maneuvering at 30 knots with tight screens reduced carrier hits by 25%, while night CAPs with F6F-5Ns and decoy transports cut night losses by diverting 10% of attacks.

U.S. Submarine Tactics Supporting Anti-Kamikaze Efforts

Submarines played a key role in disrupting Kamikaze logistics. USS Barb sank three supply ships off Luzon on 5th January, USS Spadefish hit a troop transport near Iwo Jima on 20th February, and USS Trigger (SS-237) sank two freighters off Kyushu on 10th April, starving Okinawa bases. USS Nautilus’s recon of Kanoya airfield on 8th April guided strikes destroying 50+ planes. Early actions like USS Flying Fish’s sinkings off Saipan (20th June 1944) and USS Darter’s sinking of cruiser Atago (23rd October) hampered preparations. Over 20 support vessels sank by June 1945, weakening Kikusui sustainability.

Japanese Naval Strategy During Kikusui Waves

Japan’s naval strategy during Okinawa’s Kikusui waves, orchestrated by Admiral Soemu Toyoda, aimed to maximize Kamikaze devastation through coordinated mass attacks and deception. Aircraft staged from Kyushu and Formosa launched waves like Kikusui I (6th April, 355 planes), with destroyers (e.g., Yahagi) as decoys to draw U.S. carriers. Operation Ten-Go on 7th April saw battleship Yamato sortie as a sacrificial lure, sunk by 386 U.S. aircraft, enabling 150 Kamikazes to strike (e.g., USS Maryland, 35 killed). “Bait” G4M Bettys flew high to distract CAPs, while Zeros skimmed waves at 50 feet, as in Kikusui VI (11th May), sinking 36 ships but exhausting Japan’s air and naval reserves.

Conclusion

From Saipan (15th June 1944) to Okinawa (22nd June 1945), Kamikaze attacks escalated from early desperation to the Kikusui climax, sinking 36 U.S. ships and damaging 368, with over 4,900 sailors killed. U.S. naval and submarine tactics mitigated losses, while Japan’s naval strategy inflicted heavy damage but failed to alter the war’s course, ending with Japan’s surrender on 15th August 1945 after Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto Japanese Aces by Full Name A6M Operators Japanese Aces by Surname Imperial Japanese Naval air units Japanese Aces by service and highest number of Kills

The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II

Bibliography:

- Bueschel, Richard M. Mitsubishi A6M1/2/-2N Zero-Sen in Imperial Japanese Naval Air Service. Canterbury, Kent, UK: Osprey Publications Ltd., 1970. ISBN 0-85045-018-7.

- Francillon, René J. The Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero-Sen (Aircraft in Profile number 129). Leatherhead, Surrey, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1966.

- Francillon, René J. The Mitsubishi A6M3 Zero-Sen ("Hamp") (Aircraft in Profile number 190). Leatherhead, Surrey, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1967.

- Green, William and Swanborough, Gordon. The Great Book of Fighters. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-7603-1194-3.

- Jackson, Robert. Combat Legend: Mitsubishi Zero. Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, UK: Airlife Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-84037-398-9.

- Juszczak, Artur. Mitsubishi A6M Zero. Tarnobrzeg, Poland/Redbourn, UK: Mushrom Model Publications, 2001. ISBN 83-7300-085-2.

- Marchand, Patrick and Takamori, Junko. (Illustrator) A6M Zero (Les Ailes de Gloire 2) (in French). Le Muy, France: Editions d’Along, 2000. ISBN 2-914403-02-X.

- Mikesh, Robert C. Warbird History: Zero, Combat & Development History of Japan's Legendary Mitsubishi A6M Zero Fighter. Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International, 1994. ISBN 0-87938-915-X.

- Mikesh, Robert C. and Watanabe, Rikyu. (Illustrator) Zero Fighter. London: Jane's Publishing Company Ltd., 1981. ISBN 0-7106-0037-2.

- Nohara, Shigeru. A6M Zero in Action(Aircraft #59). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, Inc., 1983. ISBN 0-89747-141-5.

- Nohara, Shigeru. Mitsubishi A6M Zero Fighter (Aero Detail 7) (in Japanese with English captions). Tokyo, Japan: Dai Nippon Kaiga Company Ltd., 1993. ISBN 4-499 22608-2.

- Okumiya, Masatake and Hiroikoski, Jiro (with Caidin, Martin). Zero! The Story of Japan's Air War in the Pacific: 1941-45. New York: Ballantine Books, 1956. No ISBN.

- Richards, M.C. and Smith Donald S. Mitsubishi A6M5 to A6M8 'Zero-Sen' ('Zeke 52')(Aircraft in Profile number 236). Windsor, Berkshire, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1972.

- Sakaida, Henry. Imperial Japanese Navy Aces, 1937–45. Botley, Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 1998. ISBN 1-85532-727-9.

- Sakaida, Henry. The Siege of Rabaul. St. Paul, Minnesota: Phalanx Publishing, 1996. ISBN 1-883809-09-6.

- Sheftall, M.G. Blossoms in the Wind: Human Legacies of the Kamikaze. New York: NAL Caliber, 2005. ISBN 0-451-21487-0.

- Willmott, H.P. Zero A6M. London: Bison Books, 1980. ISBN 0-89009-322-9.

- Wilson, Stewart. Zero, Hurricane & P-38, The Story of Three Classic Fighters of WW2 (Legends of the Air 4). Fyshwick, Australia: Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd., 1996. ISBN 1-875671-24-2.

Magazine References: +

- Airfix Magazines (English) - http://www.airfix.com/

- Avions (French) - http://www.aerostories.org/~aerobiblio/rubrique10.html

- FlyPast (English) - http://www.flypast.com/

- Flugzeug Publikations GmbH (German) - http://vdmedien.com/flugzeug-publikations-gmbh-hersteller_verlag-vdm-heinz-nickel-33.html

- Flugzeug Classic (German) - http://www.flugzeugclassic.de/

- Klassiker (German) - http://shop.flugrevue.de/abo/klassiker-der-luftfahrt

- Le Fana de L'Aviation (French) - http://boutique.editions-lariviere.fr/site/abonnement-le-fana-de-l-aviation-626-4-6.html

- Le Fana de L'Aviation (French) - http://www.pdfmagazines.org/tags/Le+Fana+De+L+Aviation/

- Osprey (English) - http://www.ospreypublishing.com/

- Revi Magazines (Czech) - http://www.revi.cz/

Web References: +

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_air_groups_of_the_Imperial_Japanese_Navy

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mitsubishi_A6M_Zero

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Japanese_Navy_Air_Service

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Mitsubishi_A6M_Zero_operators

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kamikaze

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tetsuz%C5%8D_Iwamoto

- http://mitsubishi_zero.tripod.com/

- http://ww2db.com/aircraft_spec.php?aircraft_model_id=3

- http://www.combinedfleet.com/ijna/a6m.htm

- http://www.combinedfleet.com/ijna/a6m-k.htm

- http://www.combinedfleet.com/ijna/a6m-n.htm

- http://www.j-aircraft.com/research/WarPrizes.htm

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

If you love our website please donate so we can make this site even better !!

-off-the-Marianas-23rd-Feb-1944-80-G-218422.jpg)

-off-the-Marianas-23rd-Feb-1944-80-G-218423.jpg)

-off-the-Marianas-23rd-Feb-1944-80-G-218602.jpg)

-by-25-feet-or-less-off-Okinawa-4th-May-1945-80-G-334505.jpg)

-knocks-down-a-Japanese-plane-seen-from-the-Essex-(CV-9)-off-Marianas-22nd-Feb-1944-80-G-373624.jpg)

-after-being-hit-by-Kamikaze-planes-during-the-Okinawa-operation-11th-May-1945-80-G-274266.jpg)

-after-being-hit-by-Kamikaze-planes-during-the-Okinawa-operation-11th-May-1945-80-G-274266b.jpg)

-after-being-hit-by-Kamikaze-planes-during-the-Okinawa-operation-11th-May-1945-80-G-323712.jpg)

-after-being-hit-by-Kamikaze-planes-during-the-Okinawa-operation-11th-May-1945-80-G-373792.jpg)

-after-being-hit-by-Kamikaze-planes-during-the-Okinawa-operation-11th-May-1945-80-G-K-5271.jpg)

-after-being-hit-by-Kamikaze-planes-during-the-Okinawa-operation-11th-May-1945-80-G-K-5274.jpg)

-pictured-after-being-hit-by-a-kamikaze-aircraft-off-Okinawa-7th-Apr-1945-04.jpg)

-pictured-after-being-hit-by-a-kamikaze-aircraft-off-Okinawa-7th-Apr-1945-05.jpg)

-pictured-after-being-hit-by-a-kamikaze-aircraft-off-Okinawa-7th-Apr-1945-06.jpg)

-pictured-after-being-hit-by-a-kamikaze-aircraft-off-Okinawa-7th-Apr-1945-07.jpg)

-pictured-after-being-hit-by-a-kamikaze-aircraft-off-Okinawa-7th-Apr-1945-ASC1.jpg)

-pictured-after-being-hit-by-a-kamikaze-aircraft-off-Okinawa-7th-Apr-1945-ASC2.jpg)

-about-to-be-hit-by-a-Japanese-A6M-Zero-Kamikaze-while-operating-off-Okinawa-on-11th-April-1945-NH-62696.jpg)

-after-a-near-miss-by-Japanese-air-attack-19th-June-1944-80-G-45904.jpg)

-viewed-from-USS-Hornet-(CV-12)-operating-near-the-Marianas-1st-Aug-1944-80-G-367248.jpg)

-and-USS-Belleau-Wood-(CVL-24)-both-hit-by-a-Japanese-Kamikazes-operating-off-Philippines-30th-Oct-1945-80-G-326798.jpg)

-after-she-was-hit-be-a-Kamikaze-of-Samar-Battle-of-Leyte-Gulf-on-25th-Oct-1944-80-G-270516.jpg)

-after-a-250kg-bomb-hit-the-flight-and-hangar-decks-25th-Oct-1944-NH-71528.jpg)

-Kamikaze-attack-25th-Oct-1944-01.jpg)

-during-a-Kamikarze-attack-seen-from-USS-Gambier-Bay-(CVE-73)-during-the-Battle-of-Leyte-Gulf-25th-Oct-1944-ASC2.jpg)

-forward-flight-deck-on-fire-hit-by-several-Kamikazes-off-Iwo-Jima-21st-Feb-1945-80-G-273631.jpg)

-hit-by-bombs-from-a-Japanese-aircraft-viewed-from-USS-Santa-Fe-(CL-60)-19th-Mar-1945-80-G-273882.jpg)

-after-being-hit-by-Kamikaze-planes-during-the-Okinawa-operation-11th-May-1945-80-G-274266.jpg)

-burning-after-a-kamikaze-attack-during-the-battle-of-Okinawa-14th-May-1945.jpg)