The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II

United States Navy aircraft carrier USS Essex

CV-9 CVA-9 CVS-9

-at-sea-with-an-overload-of-aircraft-on-her-flight-deck-14th-May-1944-80-G-373580.jpg) |

-assigned-Carrier-Air-Group-11-(CVG-11)-and-deployed-to-the-Western-Pacific-16th-July-1956-to-26th-Jan-1957.jpg) |

USS Essex (CV-9)

Name: Essex

Namesake: USS Essex (A town and county in Massachusetts 1799)

Ordered: 3 July 1940

Builder: Newport News Shipbuilding

Laid down: 28 April 1941

Launched: 31 July 1942

Commissioned: 31 December 1942

Decommissioned: 9 January 1947

Recommissioned: 15 January 1951

Decommissioned: 30 June 1969

Reclassified: CVA-9, October 1952; CVS-9, March 1960

Stricken: 1 June 1973

Fate: Scrapped, 1973General characteristics (as built)

Class and type: Essex-class aircraft carrier

Displacement: 27,100 long tons (27,500 t) (standard); 36,380 long tons (36,960 t) (full load)

Length: 820 feet (249.9 m) (wl); 872 feet (265.8 m) (o/a)

Beam: 93 ft (28.3 m)

Draft: 34 ft 2 in (10.41 m)

Installed power: 8 × Babcock & Wilcox boilers; 150,000 shp (110,000 kW)

Propulsion: 4 × geared steam turbines; 4 × screw propellers

Speed: 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph)

Range: 14,100 nmi (26,100 km; 16,200 mi) at 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph)

Complement: 2,600 officers and enlisted men

Armament: 12 × 5 in (127 mm) DP guns; 32 × 40 mm (1.6 in) AA guns; 46 × 20 mm (0.8 in) AA guns

Armor: Waterline belt: 2.5–4 in (64–102 mm); Deck: 1.5 in (38 mm); Hangar deck: 2.5 in (64 mm); Bulkheads: 4 in (102 mm)

Aircraft carried: 36 × Grumman F4F Wildcat; 36 × Douglas SBD Dauntless; 18 × Grumman TBF Avenger

USS Essex (CV/CVA/CVS-9) was an aircraft carrier and the lead ship of the 24-ship Essex class built for the United States Navy during World War II. She was the fourth US Navy ship to bear the name. Commissioned in December 1942, Essex participated in several campaigns in the Pacific Theater of Operations, earning the Presidential Unit Citation and 13 battle stars. Decommissioned shortly after the war, she was modernized and recommissioned in the early 1950s as an attack carrier (CVA), eventually becoming an antisubmarine aircraft carrier (CVS). In her second career, she served mainly in the Atlantic, playing a role in the Cuban Missile Crisis. She also participated in the Korean War, earning four battle stars and the Navy Unit Commendation. She was the primary recovery carrier for the Apollo 7 space mission.

She was decommissioned for the last time in 1969 and sold by the Defense Reutilization and Marketing Service for scrap on 1 June 1973.[1]

USS Essex (CV-9) launching and christening at the Newport New 31st July 1942

USS Essex (CV-9) launching with Mrs Artemus Gates is about to christen at the Newport New 31st July 1942

USS Essex (CV-9) afloat in the James River immediately after her launching 31st July 1942

USS Essex (CV-9) afloat in the James River immediately after her launching 31st July 1942

Description and construction

Essex was laid down on 28 April 1941 by Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co. After the Pearl Harbor attack, her building contract (along with the same for CV-10 and CV-12) was reworked. After an accelerated construction, she was launched on 31 July 1942, sponsored by Alice Trubee Davison, the wife of the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Air. She was commissioned on 31 December 1942, with Captain Donald B. Duncan commanding.[2]

Flight deck arrangements

The USS Essex (CV-9) featured an aircraft carrier deck designed to support extensive air operations, with a long flight deck and two aircraft elevators located on the centerline. After undergoing the SCB-125 modernization in the 1950s, it was updated with an angled flight deck, allowing simultaneous launch and recovery of aircraft, and the addition of an enclosed "hurricane bow" to improve seakeeping in rough weather. This arrangement enabled the carrier to handle newer, faster aircraft with increased operational efficiency.

Propulsion

The Essex-class carriers, including USS Essex, were powered by eight Babcock & Wilcox boilers feeding four geared steam turbines that drove four shafts, providing an output of 150,000 shaft horsepower. This setup allowed the ship to reach speeds exceeding 33 knots, essential for keeping pace with the fast-moving task forces and facilitating aircraft launch speeds. The propulsion plant was arranged to maximize redundancy, with each pair of boilers and turbines serving an individual shaft, enhancing survivability in combat.

Armament

USS Essex had an armored hangar deck with approximately 2.5 inches of armor plating to protect aircraft and maintenance facilities from bomb and shell hits. The side belt armor, primarily intended to protect the propulsion machinery and ammunition magazines, was around 2.5 inches thick. Vital areas, including ammunition storage, were further protected by reinforced bulkheads and armor around the magazines, providing layered protection against damage from air and surface threats.

Fire control and electronics

The Essex class employed advanced fire control systems for both its main guns and anti-aircraft weapons, including the Mk 37 fire control system for the 5-inch guns, which provided radar-based targeting accuracy. Radar systems on the Essex included air-search radar for detecting incoming threats, surface-search radar for tracking ships, and radar for assisting in fighter direction, enabling early warning and coordinated air defense. Electronic countermeasures were also added later to counter enemy radar and missile threats.

Armor

USS Essex had an armored hangar deck with approximately 2.5 inches of armor plating to protect aircraft and maintenance facilities from bomb and shell hits. The side belt armor, primarily intended to protect the propulsion machinery and ammunition magazines, was around 2.5 inches thick. Vital areas, including ammunition storage, were further protected by reinforced bulkheads and armor around the magazines, providing layered protection against damage from air and surface threats.

Pearl Harbor the trigger point for America to enter into WWII

Service history - World War II

Following her accelerated builder's trials and shakedown cruise, Essex moved to the Pacific in May 1943. Departing from Pearl Harbor, she participated with Task Force 16 (TF 16) in carrier operations against Marcus Island. On 31 August 1943, she was designated the flagship of TF 14 and struck Wake Island on 5 and 6 October. On 11 November, she took part in carrier operations during the Rabaul strike, alongside Bunker Hill and USS Independence. She then launched an attack with Task Group 50.3 (TG 50.3) against the Gilbert Islands where she took part in her first amphibious assault during the Battle of Tarawa. After refueling at sea, she cruised as the flagship of TG 50.3 to attack Kwajalein on 4 December. Her second amphibious assault delivered in company with TG 50.3 was against the Marshall Islands on 29 January to 2 February 1944.

Essex, in TG 50.3, now joined with TG 58.1 and TG 58.2 to constitute Task Force 58, the "Fast Carrier Task Force," launched an attack against Truk between 17 and 18 February 1944 during which eight Japanese ships were sunk. While en route to the Mariana Islands to sever Japanese supply lines, the carrier force was detected and subjected to a prolonged aerial attack which it repelled successfully. It then continued with the scheduled attack upon Saipan, Tinian, and Guam on 23 February 1944.[2]

USS Essex (CV-9) after her San Francisco refit 15th April 1944

USS Essex (CV-9) after her San Francisco refit 15th April 1944.

After this operation, Essex proceeded to San Francisco for her single wartime overhaul, after which, Essex became the carrier for Air Group 15, the "Fabled Fifteen" commanded by the U.S. Navy's top ace of the war, David McCampbell. She then joined carriers Wasp and San Jacinto in TG 12.1 to strike Marcus Island on 19 to 20 May 1944, and Wake, on 23 May 1944. She deployed with TF 58 to support the occupation of the Marianas on 12 June to 10 August; sortied with TG 38.3 to lead an attack against the Palau Islands on 6 to 8 September, and Mindanao on 9 to 10 September with enemy shipping as the main target, and remained in the area to support landings on Peleliu. On 2 October, she weathered a typhoon and four days later departed with Task Force 38 (TF 38) for the Ryukyus.[2][note 1]

For the remainder of 1944, she continued her frontline action, participating in strikes against Okinawa on 1 October, and Formosa from 1 to 14 October, covering the Leyte landings, taking part in the Battle of Leyte Gulf 24 to 25 October, and continuing the search for enemy fleet units until 30 October, when she returned to Ulithi, Caroline Islands, for replenishment. She resumed the offensive and delivered attacks on Manila and the northern Philippine Islands during November. On 25 November, for the first time, Essex received damage. A kamikaze hit the port edge of her flight deck, landing among planes fueled for takeoff, and causing extensive damage, killing 15, and wounding 44.[3]

Following quick repairs, she operated with the task force off Leyte supporting the occupation of Mindoro 14 to 16 December 1944. She rode out Typhoon Cobra and made a special search for survivors afterward. With TG 38.3, she participated in the Lingayen Gulf operations, launched strikes against Formosa, Sakishima, Okinawa, and Luzon. Entering the South China Sea in search of enemy surface forces, the task force pounded shipping and conducted strikes on Formosa, the China coast, Hainan, and Hong Kong. Essex withstood the onslaught of the third typhoon in four months on 20 and 21 January 1945 before striking again at Formosa, Miyako-jima, and Okinawa on 26 and 27 January.

Typhoon Cobra

14th to 19th December 1944

USS Cowpens (CVL 25) Typhoon Cobra hit the Third Fleet on 18th Dec 1944

During Typhoon Cobra in 14th to 19th December 1944, a total of nine U.S. Navy ships sustained significant damage due to the severe storm conditions. The typhoon, which struck the Third Fleet in the Philippine Sea, caused extreme waves and winds that battered many vessels in the fleet, in addition to sinking three destroyers: USS Hull (DD-350); USS Monaghan (DD-354); USS Spence (DD-512) and caused the death of 790 sailors.

USS Hull (DD-350) - USS Monaghan (DD-354) - USS Spence (DD-512)

These destroyers capsized and sank due to the intense conditions, and 790 sailors lost their lives in the disaster.

Other ships damaged during Typhoon Cobra

Aircraft Carriers: The storm caused substantial damage to several carriers, including the USS Monterey (CVL-26), which suffered a severe onboard fire that was difficult to control. Future U.S. President Gerald Ford, serving as a young officer, helped to contain the blaze. Other carriers, such as USS Cowpens (CVL-25), USS San Jacinto (CVL-30), and USS Altamaha (CVE-18), were also damaged.

USS Massachusetts (BB-59) was damaged by Typhoon Cobra December 1944

The battleship USS Massachusetts (BB-59), among others, sustained structural damage from the waves and heavy rolling conditions.

Battleships: The battleship USS Massachusetts (BB-59), among others, sustained structural damage from the waves and heavy rolling.

Cruisers and Destroyers: Several cruisers and destroyers suffered structural damage, fuel loss, and equipment failures. Some destroyers reported near-capsize events, with USS Dewey (DD-349) and USS Aylwin (DD-355) narrowly avoiding the same fate as the three lost destroyers.

In total, over 100 aircraft were lost on various carriers, washed overboard or damaged beyond repair due to the severe weather. The disaster led to significant changes in Navy weather forecasting, safety protocols, and training to prevent similar incidents in the future.

On 18 December 1944, elements of Admiral William Halsey’s Third Fleet plowed into a powerful Pacific Typhoon east of the Philippines. By the time the tropical cyclone passed, three U.S. destroyers had been sunk, Spence (DD-512), Hull (DD-350) and Monaghan (DD-354) with 775 of their crewmen lost and only 91 rescued. The light carrier Monterey (CVL-26) suffered a serious fire during the storm, losing three crewmen and 18 aircraft. Total casualties across the entire force, including the three destroyers, included 790 killed and 146 planes smashed, washed overboard, or jettisoned. Twenty-seven ships were damaged, eleven requiring major repairs, including Monterey.

Following the Battle of Leyte Gulf on 24–25 October, the Third Fleet Fast Carrier Task Force (TF-38) was essentially tied down providing air cover to Leyte as the U.S. Army Air Force was unable to get onto airfields on Leyte and provide their own air-cover to troops ashore, primarily due to abysmal whether that rendered all but the airfield at Tacloban unusable due to mud. (Tacloban had very limited capacity even under ordinary circumstances.) As a result, rather than roaming the Western Pacific, Halsey’s carriers were subject to increasing Japanese kamikaze attacks while tied down off the eastern Philippines. (Actually, more U.S. ships would by sunk, put out of action, or damaged, and with more casualties in the two months it took the Army to secure Leyte, than during the Battle of Leyte Gulf itself, which will be the subject of the next H-gram.) Nevertheless, TF-38 stood in there and kept pounding Japanese airfields with airstrikes and fighter sweeps throughout the Philippines but especially on the main island of Luzon, which MacArthur had originally slated for invasion in mid-December. Halsey’s carriers were conducting operations in support of this planned invasion (which would be postponed until January 1945, but that was not known yet) when the weather began seriously to deteriorate on 16 December, gravely impacting at-sea refueling operations. Many of Halsey’s ships were low on fuel due to the continuous high-tempo combat operations

As of 17 December 1944, TF-38 consisted of seven Essex-class fleet carriers, six Independence-class light carriers, eight battleships, four heavy cruisers, eleven light cruisers and about 50 destroyers. TF-38 was joining with the Third Fleet refueling group that consisted of twelve fleet oilers, three fleet tugs, five destroyers, ten destroyer escorts, and five escort carriers with replacement planes.

With the technology of the time, there was little capability to track typhoons, and avoiding them depended greatly on the “Seaman’s Weather Eye.” The problem with this typhoon was that although it was very powerful, it was very compact and not very big, so warning signs were not apparent until the typhoon was very close, much closer than expected. Initially, as the weather rapidly deteriorated on 17 December, there were no signs that a typhoon was approaching, and the weather forecasters on the Third Fleet staff and on the carriers repeatedly misdiagnosed the situation. As seas built on the morning of the 17th, refueling became increasingly hazardous, with cases of parted hoses and lines and several near-collisions.

At 1251, Halsey gave orders to belay fueling. Halsey also gave orders for ships that had not been able to refuel to ballast down with salt water. However, several ships delayed too long in doing so in hopes that they would be able to take fuel as soon as the seas subsided. Vice Admiral John McCain, Commander of CTF-38, followed Halsey’s order, except for those orders pertaining to the destroyers Spence, Hickox (DD-673) and Maddox (DD-731) which were so low on fuel (10–15%) that they might not make it 24 hours. The Spence and Hickox were ordered to remain with the oilers and grab fuel if the seas allowed. As a result, the three destroyers delayed ballasting down, in the case of Spence too long, which would prove fatal.

Several attempts by Halsey to maneuver the fleet to areas more conducive to refueling put parts of the fleet directly in the path of the storm, unfortunately. For a time, the fleet was on the same course as the storm but slightly ahead and faster, which gave a misleading impression that conditions were slowly improving. It wasn’t until about 0400 on the 18th that it became apparent that the fleet had stumbled into a very serious weather condition. It wasn’t until about 1000 that the barometer started falling precipitously in a manner indicative of an approaching typhoon and not just a bad weather front. By 1400 the wind reached hurricane strength, and several of the carriers were so close that they could see the eye of the typhoon on radar.

In the end, a number of ships ultimately wound up in the most dangerous quadrant, with some passing right through the eye on 18 December. Halsey’s biggest mistake was waiting too long to give individual ships the okay to break out of formation to ride out the storm independently, giving the order only at 1149 (although some commanding officers were already doing so on their own initiative). Others who tried too long to stay in formation caused their ships to take an even worse beating than necessary. At 1314, Halsey issued a typhoon warning, the first official traffic referencing a typhoon. By this time, three of Halsey’s destroyers had already gone down, and others were fighting to survive.

The poor sea-keeping qualities of the Independence-class light carriers (which had been hastily designed and built on light cruiser hulls) became readily apparent by 0900 on 18 December. All were rolling severely. Langley (CVL-27) rolled 70-degrees at one point. Seven planes on Cowpens (CVL-25) were washed overboard and one plane that broke loose started a fire that was quickly extinguished. On San Jacinto (CVL-30), a fighter plane broke loose on the hangar deck and smashed seven other aircraft. By contrast, the escort carriers, with their hull design based on merchant ships, actually fared better than the light carriers, suffering less damage, although about 90 of the replacement aircraft were lost.

The light carrier Monterey (CVL-26) fared the worst, as a plane broke free on the hangar deck and smashed into a bulkhead at 0911, starting a serious fire, that was put out only after three sailors were killed and many more injured, with 18 planes destroyed by fire or washed overboard and another 16 planes seriously damaged as they careened about the hangar bay during severe rolls, exacerbated by the fact that Monterey also lost steerageway when the boiler rooms were evacuated shortly after the fire started. Of note, future President Lieutenant Gerald R. Ford was serving as the General Quarters Officer of the Deck. With Captain Stuart H. Ingersoll on the bridge, Ford was ordered to go down to the hangar deck and report on the fire, noting later that he was nearly washed overboard while planes were smashing into each other. Fortunately, the crew got the fire and the planes under control along with steerage, and Monterey weathered the typhoon, although she required repairs at Bremerton until April 1945.

Spence (DD-512) was a new Fletcher-class destroyer, much more stable than the older Farragut-class, but she was in trouble even before the typhoon hit, with her fuel state down to 15%, which meant she had less than 24 hours’ steaming time at eight knots. After unsuccessfully attempting to refuel from battleship New Jersey (BB-62) on the 17th, she was then ordered to accompany the oiler group to refuel at the first chance, which never came. Her skipper began water-ballasting too late and she began rolling heavily to port. Water entered through the ventilators and short-circuited the distribution board. Then the rudder jammed hard right. At 1110, Spence took a deep roll to port, recovered, and then took another one from which she did not recover, going down with 317 of her crew (23 survived), the first destroyer to sink in the typhoon.

By 1100 the destroyer Hull (DD-350), commanded by Lieutenant Commander J.A. Marks, was in serious trouble. Marks was responsible for screening a group of four oilers and maintained station for too long. Hull was at 70% fuel state and had not taken on saltwater ballast in the tanks. (The Court of Inquiry determined that standard procedures at the time did not require re-ballasting with that much fuel on board, but the failure to do so nonetheless contributed to her loss. Although regulations didn’t require it, re-ballasting was a lesson from an earlier typhoon that had not been learned.) In addition, as an older Farragut-class destroyer, Hull had over 500 tons of extra weapons and equipment added, making her top heavy. By 1100 the wind had reached 100 knots, and Hull was rolling 50 degrees, which just before noon reached 70 degrees. She survived several such rolls before a gust of wind estimated at 110 knots pinned her on her beam ends, and water poured down her funnels and into the pilothouse and she capsized and sank a few minutes after noon with 202 of her crew (62 survived.)

The Farragut-class destroyer Dewey (DD-349) almost met the same fate as Hull, but was saved by the prompt jettisoning of topside weights, re-ballasting with salt water, and the loss of her funnel, which reduced sail area, along with a lot of bailing and pumping. Farragut-class Aylwin (DD-355) also barely survived as she passed very close to the eye wall. By 1100, Aylwin had lost her engines and steering control, rolled 70 degrees to port and stayed there for 20 minutes. Regaining steering control intermittently, Lieutenant Commander W. K. Rogers, through some incredible ship handling was able to hold her up, but temperatures in the engine rooms reached 180 degrees as the blowers failed and the engine rooms had to be evacuated. The ship’s engineering officer, Lieutenant E. R. Rendahl and Machinist’s Mate T. Sarenski remained at their posts despite the intense heat in order to protect the electrical circuits. When they too finally evacuated, they had to take off their life jackets to fit through the escape hatch to the deck, where they collapsed due to the temperature change and were washed overboard. Somehow, Aylwin managed to survive despite serious flooding.

Farragut-class destroyer Monaghan (DD-354) was not so lucky as Dewey and Aylwin. Her fuel tanks were 76 percent full, and although she attempted to ballast down, with great difficulty as valves stuck, it was too late. At 1130, Monaghan lost electric power and the steering engine failed. After several very heavy rolls she foundered just before noon along with 256 of her crew (only six survived). Monaghan had 12 battle stars, having sunk a Japanese midget submarine inside Pearl Harbor during the air attack, served at Midway, performed valiantly in the Battle of the Komandorski Islands, drove the Japanese submarine I-7 onto the rocks in the Aleutians and fought in other battles, but she was defeated by a storm.

By the time the typhoon moved through, numerous ships had been damaged. Those that required major repair included Anzio (CVE-57), Cape Esperance (CVE-88), Baltimore (CA-68), Miami (CL-89), Dewey (DD-349), Aylwin (DD-355), Buchanan (DD-484), Dyson (DD-572), Hickox (DD-673), Benham (DD-796), Donaldson (DE-44), and Melvin R. Nawman (DE-416.) Other ships damaged included four light carriers, three escort carriers, one battleship, one destroyer, two destroyer escorts, and an oiler.

A hero of the Typhoon was the destroyer escort Tabberer (DE-418), which had her foremast and radio antennas washed away, and was taking 60 degree rolls. As evening approached on the 18th, Tabberer encountered and rescued a survivor of Hull. At that point her commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Henry L. Plage, commenced a box search, despite her own serious state. Over the next 51 hours, Plage didn’t receive (or ignored) repeated orders from Admiral Halsey for all ships to regroup at Ulithi. (Halsey did not learn that any of his ships had been sunk until 0225 on 19 December.) During this period, Tabberer rescued 55 survivors (41 from Hull and 14 from Spence) before being relieved by two destroyer escorts. Tabberer rescued ten of the Hull survivors at night. Many were rescued by Hull swimmers, who went over overboard with lines tied, in order to bring the survivors to nets and life rings on Tabberer’s side, while other crewmen used rifle fire to drive away sharks. Lieutenant Commander Plage was awarded a Legion of Merit and Tabberer a Navy Unit Commendation (the first ever awarded, although others were awarded retroactively for earlier actions). The destroyer Brown (DD-546) rescued the six survivors from Monaghan and 13 survivors of Hull. All told, 93 crewmen who had been washed overboard or survived the sinking of their ships were rescued.

A Court of Inquiry subsequently convened at Ulithi on 26 December 1944 aboard the destroyer tender Cascade (AD-16), with Admiral Chester A. Nimitz in attendance and presided by Vice Admiral John Hoover. The Court of Inquiry placed responsibility for losses and storm damage on Admiral Halsey but ascribed no negligence, stating that Halsey’s mistakes “were errors in judgment committed under stress of war operations and stemming from a commendable desire to meet military requirements.” In retrospect, Halsey should not have attempted any refueling operations on the morning of 18 December, but that would have required him to know where the center of the typhoon was before he did. The Court of Inquiry also determined that the commanding officers of Hull, Monaghan, and Spence maneuvered too long in an attempt to keep station, which “prevented them from concentrating early enough on saving their ships.” In the opinion of Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison, it was “too much to expect of junior destroyer skippers-classes of 1937 and 1938, Naval Academy-to have pitted their brief experience against the lack of typhoon warnings and their own want of fuel.”

However, in the words of Fleet Admiral Nimitz, “The time for taking all measures for a ship’s safety is while still able to do so. Nothing is more dangerous than for a seaman to be grudging in taking precautions lest they turn out to have been unnecessary. Safety at sea for a thousand years has depended on exactly the opposite philosophy.”

Sources are: History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. 13: The Liberation of the Philippines, by Samuel Eliot Morison; and the Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS).

For the remainder of the war, she operated with TF 58, conducting attacks against the Tokyo area on 16 and 17 February. On 25 February 1945, she was deployed to neutralize the enemy's air power before the landings on Iwo Jima and to cripple the aircraft-manufacturing industry. She sent support missions against Iwo Jima and neighboring islands, but from 23 March to 28 May, was employed primarily to support the conquest of Okinawa. In the closing days of the war, Essex took part in the final telling raids against the Japanese home islands on 10 July to 15 August 1945. Following the surrender of Japan, she continued defensive combat air patrols until 3 September, when she was ordered to Bremerton, Washington, for inactivation. She arrived at Puget Sound on 15 September.[4]

The fourth Essex (CV-9) was laid down on 28 April 1941; by Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co., at Newport News, Va.; launched on 31 July 1942; sponsored by Mrs. Artemus L. Gates, wife of the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Air; and commissioned on 31 December 1942, Capt. D.B. Duncan in command. She was reclassified to an attack aircraft carrier (CVA-9) on 1 October 1952, and an antisubmarine warfare support aircraft carrier (CVS-9) on 8 March 1960.

Following her shakedown cruise Essex sailed to the Pacific in May 1943 to begin a succession of victories which would bring her to Tokyo Bay. Departing Pearl Harbor, she participated with TF 15 in carrier operations against Marcus Island (31 August 1943); was designated flagship of TF 14 and struck Wake Island (5-6 October); launched an attack with TG 50.3 against the Gilbert Islands where she also took part in her first amphibious assault, the landing on Tarawa (18-23 November). Refueling at sea, she cruised as flagship of TG 50.3 to attack Kwajalein (4 December). Her second amphibious assault delivered in company with TG 58.2 was against the Marshalls (29 January-2 February 1944).

Essex in TG 58.2 now joined with TG 58.1 and 58.3, to constitute the most formidable carrier striking force to date, in launching an attack against Truk (17-18 February) during which eight Japanese ships were sunk. En route to the Marianas to sever Japanese supply lines, the carrier force was detected and received a prolonged aerial attack which it repelled in a businesslike manner and then continued with the scheduled attack upon Saipan, Tinian and Guam (23 February).

USS Essex (CV-9) flight deck during her shakedown cruise 20th Mar 1943

USS Essex (CV-9) flight deck during her shakedown cruise 20th Mar 1943

Essex (CV-9) scene on the flight deck, looking aft from the carrier's island during her shakedown cruise, 20 March 1943. Planes parked on deck are F6F-3 fighters (in foreground, with wings folded) and SBD-4 scout bombers. Official U.S. Navy photograph now in the collections of the National Archives. Catalog#: 80-G-K-698.

After this operation Essex proceeded to San Francisco for her single wartime overhaul. She then joined carriers Wasp (CV-18) and San Jacinto (CVL-30) in TG 12.1 to strike Marcus Island (19-20 May) and Wake (23 May). She deployed with TF 58 to support the occupation of the Marianas (12 June-10 August); sortied with TG 38.3 to lead an attack against the Palau Islands (6-8 September), and Mindanao (9-10 September) with enemy shipping as the main target, and remained in the area to support landings on Peleliu. On 2 October she weathered a typhoon and 4 days later departed with TF 38 for the Ryukyus.

For the remainder of 1944 she continued her frontline action, participating in strikes against Okinawa (10 October), and Formosa (12-14 October), covering the Leyte landings, taking part in the battle for Leyte Gulf (24-25 October), and continuing the search for enemy fleet units until 30 October when she returned to Ulithi, Caroline Islands, for replenishment. She resumed the offensive and delivered attacks on Manila and the northern Philippine Islands during November. On 25 November, for the first time in her far-ranging operations and destruction to the enemy, Essex received injury. A kamikaze hit the port edge of her flight deck landing among planes gassed for takeoff, causing extensive damage, killing 15, and wounding 44.

This "cramped her style" very little. Following quick repairs we find her with 3d Fleet off Luzon supporting the occupation of Mindoro (14-16 December). She rode out the typhoon of 18 December and made special search for survivors afterwards. With TG 38.3 she participated in the Lingayen Gulf operations, launched strikes against Formosa, Sakishima, Okinawa, and Luzon. Entering the South China Sea in search of enemy surface forces, the task force pounded shipping and conducted strikes on Formosa, the China coast, Hainan, and Hong Kong. Essex withstood the onslaught of the third typhoon in 4 months (20-21 January 1945) before striking again at Formosa, Miyakp Shima and Okinawa (26-27 January).

During the remainder of the war she operated with TF 58, conducting attacks against the Tokyo area (16-17, and 25 February) both to neutralize the enemy's airpower before the landings on Iwo Jima and to cripple the aircraft manufacturing industry. She sent support missions against Iwo Jima and neighboring islands, but from 23 March to 28 May was employed primarily to support the conquest of Okinawa.

Explosion of a Japanese "Judy" kamikaze plane on Essex (CV-9) carrier's flight deck, 25 November 1944. Essex was operating off Luzon. Note F6F fighter at far left, close to the water. Photographed from Ticonderoga (CV-14). National Archives photograph. Catalog#: 80-G-270736.

In the closing days of the war, Essex took part in the final telling raids against the Japanese home islands (10 July-15 August). Following the surrender, she continued defensive combat air patrols until 3 September when she was ordered to Bremerton, Wash., for inactivation. On 9 January 1947 she was placed out of commission in reserve.

Modernization endowed Essex with a new flight deck, and a streamlined island superstructure, on 15 January 1951 when recommissioned, Captain A. W. Wheelock commanding.

After a brief cruise in Hawaiian waters she began the first of three tours in Far Eastern waters during the Korean war. She served as flagship for Carrier Division 1 and TF 77. She was the first carrier to launch F2H "Banshee" twin-jet fighters on combat missions; on 16 September 1951 one of these planes, damaged in combat, crashed into aircraft parked on the forward flight deck causing an explosion and fire which killed seven. After repairs at Yokosuka she returned to front-line action on 3 October to launch strikes up to the Yalu River and provide close air support for U.N. troops.

On 1 December 1953 she started her final tour of the war, sailing the China Sea with the Peace Patrol. From November 1954 to June 1955 she engaged in training exercises, operated for 3 months with the 7th Fleet, assisted in the Tachen Islands evacuation, and engaged in air operations and fleet maneuvers off Okinawa.

In July 1955 Essex entered Puget Sound Naval Shipyard for repairs and extensive alterations, including installation of an angled flight deck. Modernization completed, she rejoined the Pacific Fleet in March 1956. For the next 14 months the carrier operated off the west coast, except for a 6-month cruise with the 7th Fleet in the Far East. Ordered to join the Atlantic Fleet for the first time in her long career, she sailed from San Diego on 21 June 1957, rounded Cape Horn, and arrived in Mayport, Fla., on 1 August.

In the fall of 1957 Essex participated as an antisubmarine carrier in the NATO exercises, "Strike Back," and in February 1958 deployed with the 6th Fleet until May when she shifted to the eastern Mediterranean. Alerted to the Middle East crisis on 14 July 1958 she sped to support the U.S. Peace Force landing in Beirut, Lebanon, launching reconnaissance and patrol missions until 20 August. Once again she was ordered to proceed to Asian waters, and transited the Suez Canal to arrive in the Taiwan operational area where she joined TF 77 in conducting flight operations before rounding the Horn and proceeding back to Mayport.

Essex joined with the 2d Fleet and British ships in Atlantic exercises and with NATO forces in the eastern Mediterranean during the fall of 1959. In December she aided victims of a disastrous flood at Frejus, France.

In the spring of 1960 she was converted into an ASW Support Carrier and was thereafter homeported at Quonset Point, R.I. Since that time she has operated as flagship of Carrier Division 18 and Antisubmarine Carrier Group Three. She conducted rescue and salvage operations off the New Jersey coast for a downed blimp; cruised with midshipmen, and was deployed on NATO and CENTO exercises. In November she joined the French navy in Operation "Jet Stream" and since that time has continued her widespread activities in protection of freedom and peace.

Essex received the Presidential Unit Citation, and 13 battle stars for World War II service; 4 battle stars and the Navy Unit Commendation for Korean war service.

Service history - 1950s

USS Essex (CV-9) flight deck wait for snowy weather to break of Korea 18th Jan 1952

USS Essex (CV-9) flight deck wait for snowy weather to break of Korea 18th Jan 1952.

On 9 January 1947, she was decommissioned and placed in reserve. Modernization endowed Essex with a new flight deck, and a streamlined island superstructure on 16 January 1951, when she was recommissioned, with Captain A. W. Wheelock commanding.[2] After a brief cruise in Hawaiian waters, she began the first of three tours in Far Eastern waters during the Korean War. She served as flagship for Carrier Division 1 and Task Force 77. She was the first carrier to launch F2H Banshees on combat missions; on 16 September 1951, one of these planes, damaged in combat, crashed into aircraft parked on the forward flight deck, causing an explosion and fire, which killed seven. After repairs at Yokosuka, she returned to frontline action on 3 October to launch strikes up to the Yalu River and provide close air support for U.N. troops. Her two deployments in the Korean War were from August 1951 – March 1952 and July 1952 – January 1953. On 1 December 1953, she started her final tour of the war, sailing in the East China Sea with what official U.S. Navy records describe as the 'Peace Patrol'.

Service history - Essex after the SCB-125 modernization 1956

USS Essex (CVA-9) after the SCB-125 modernization 1956

The USS Essex (CVA-9) as modernized underway in the South China Sea 26th Aug 1956.

In the spring of 1954, she was dispatched along with the USS Boxer to the South China Sea, between Indochina and the Philippines, while the United States considered whether to use carrier aircraft to support French troops during the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, a key battle in the First Indochina War. The United States eventually decided to not join the fighting.[5] From November 1954 – June 1955, she engaged in training exercises, operated for three months with the United States Seventh Fleet, assisted in the Tachen Islands evacuation, and engaged in air operations and fleet maneuvers off Okinawa.[2]

In July 1955, Essex entered Puget Sound Naval Shipyard for repairs and extensive alterations. The SCB-125 modernization program included installation of an angled flight deck and an enclosed hurricane bow, as well as relocation of the aft elevator to the starboard deck edge. Modernization completed, she rejoined the Pacific Fleet in March 1956. For the next 14 months, the carrier operated off the West Coast, except for a six-month cruise with the 7th Fleet in the Far East. Ordered to join the Atlantic Fleet for the first time in her long career, she sailed from San Diego on 21 June 1957, rounded Cape Horn, and arrived at Naval Station Mayport on 1 August.[2]

In the fall of 1957, Essex participated as an antisubmarine carrier in the NATO Exercise Strikeback and in February 1958, deployed with the 6th Fleet until May, when she shifted to the eastern Mediterranean. Alerted to the Middle East crisis on 14 July 1958, she sped to support the US landings in Beirut, Lebanon, launching reconnaissance and patrol missions until 20 August. Once again, she was ordered to proceed to Asian waters and transited the Suez Canal to arrive in the Taiwan operational area, where she joined TF 77 in conducting flight operations before rounding the Horn and proceeding back to Mayport. Essex joined with the 2nd Fleet and British ships in Atlantic exercises and with NATO forces in the eastern Mediterranean during the fall of 1959. In December she aided victims of a disastrous flood at Fréjus, France.

In the spring of 1960, she was converted into an ASW Support Carrier and was thereafter homeported at Quonset Point, Rhode Island. Since that time, she operated as the flagship of Carrier Division 18 and Antisubmarine Carrier Group Three. She conducted rescue and salvage operations off the New Jersey coast for a downed blimp, cruised with midshipmen, and was deployed on NATO and CENTO exercises that took her through the Suez Canal into the Indian Ocean. Her ports of call included Karachi and the British Crown Colony of Aden. In November, she joined the French navy in Operation Jet Stream.[2] On 7 November 1960, the Soviet research vessel Vityaz was reported by TASS to have been buzzed in the Arabian Sea by a Grumman S-2F Tracker from Essex. The United States Navy denied that the aircraft was buzzing the ship, claiming it was merely establishing her identity.[6]

Bay of Pigs and Cuban Missile Crisis

In April 1961, Essex steamed out of Quonset Point on a two-week 'routine training' cruise, purportedly to support the carrier qualification of a squadron of Navy pilots. Twelve A4D Skyhawks from VA-34 stationed at NAS Cecil Field, Florida, flew aboard. VS-34 aircraft had been removed to make room for VA-34's aircraft. VA-34's support enlisted crew flew aboard in C1A COD aircraft. The A4D-2 were armed with two 20 mm Mk-12 cannons loaded with 'service' ammo and one LAU-3a 19 shot 2.75 FFAR pod with 'antitank' warheads mounted on the centerline ejector rack, Station 3. After several days at sea, all their identifying markings were crudely obscured with flat gray paint. They began flying two aircraft missions by day only. Not generally known to the Essex crew, they had been tasked to provide air support to CIA-sponsored bombers during the ill-fated Bay of Pigs Invasion. Cuba's leader Castro knew the Essex was off the Cuban coast, but the US Navy denied that claim. The naval aviation part of the mission was aborted by President John F. Kennedy at the last moment and the Essex crew was sworn to secrecy. Returning home and while at sea, VA-34's aircraft were hastily repainted 'national stars and bars' by all available enlisted personnel, then flew off and landed at NAS Jacksonville, and underwent professional repainting at the NARF Naval Aviation Rework facility. The planes then flew a few miles over to her home base at NAS Cecil Field. The entire VA-34 crew was sworn to secrecy. In 1967–68, VA-34's crew was awarded the Navy and Marine Expeditionary medals.[7]

Later in 1961, Essex completed a 'People to People' cruise to Northern Europe with ports of call in Rotterdam, Hamburg, and Greenock. During the Hamburg visit, over one million visitors toured Essex. During her departure, Essex almost ran aground in the shallow Elbe River. On her return voyage to the United States, she ran into a severe North Atlantic storm (January 1962) and suffered major structural damage. In early 1962, she went into dry dock in the Brooklyn Navy Yard for a major overhaul.

Essex had just finished her six-month-long overhaul and was at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base for sea trials when President Kennedy placed a naval 'quarantine' on Cuba in October 1962, in response to the discovered presence of Soviet missiles in that country. The word 'quarantine' was used rather than 'blockade' for reasons of international law, Kennedy reasoned that a blockade would be an act of war, and war had not been declared between the U.S. and Cuba.[8] Essex spent over a month in the Caribbean as one of the US Navy ships enforcing this 'quarantine', returning home just before Thanksgiving.

Later career

USS Essex (CVS 9) welcomes The Apollo 7 astronauts WM Schirra DF Eisele and W Cunningham aboard in 22nd Oct 1968

While conducting replenishment exercises with NATO forces on 10th November 1966, Essex collided with the submerged submarine Nautilus. The submarine sustained extensive sail damage, returning to port unassisted. Aboard Essex, the hull was opened, and the ship's speed indicator equipment was destroyed, but the carrier was still able to make port unassisted. Essex subsequently reported to the Boston Naval Shipyard for an extensive overhaul and hull repairs.[9]

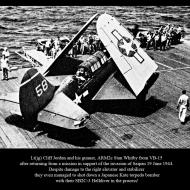

Essex was scheduled to be the prime recovery carrier for the ill-fated Apollo 1 space mission. She was to pick up Apollo 1 astronauts north of Puerto Rico on 7 March 1967 after a 14-day spaceflight. However, the mission did not take place because on 27 January 1967, the Apollo 1's crew was killed by a flash fire in their spacecraft on LC-34 at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida. Essex was the prime recovery carrier for the Apollo 7 mission. She recovered the Apollo 7 crew on 22 October 1968 after a splashdown north of Puerto Rico.[12] Essex was the main vessel on which future Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong served during the Korean War.[13]

The Apollo 7 crew is welcomed aboard Essex, 1968.

On 25 May 1968, Essex was underway in the Norwegian Sea when she was buzzed four times by a Soviet Tupolev Tu-16 heavy bomber. On the fourth pass, the plane's wing clipped the surface of the sea, and the aircraft disintegrated. The Essex launched rescue helicopters, but none of the crew on board survived. Three bodies and wreckage were recovered and transferred to a Russian destroyer via life boat.[10][11]

Essex was decommissioned on 30 June 1969[14] at Boston Navy Yard.[15] She was struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 1 June 1973 and sold by the Defense Reutilization and Marketing Service (DRMS) for scrapping on 1 June 1975.[16] Essex was scrapped at Kearny, New Jersey.[17]

Awards given to the USS Essex (CV-9)

Awards given to the USS Essex (CV-9) Navy Unit Commendation Meritorious Unit Commendation Navy Expeditionary Medal (3) China Service Medal American Campaign Medal Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal (13 battle stars) World War II Victory Medal Navy Occupation Service Medal (with Asia clasp) National Defense Service Medal (twice) Korean Service Medal (4 battle stars) Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal (2 battle stars) Philippine Presidential Unit Citation Philippine Liberation Medal (2 battle stars) United Nations Korean Medal Republic of Korea War Service Medal

United States Navy aircraft carrier USS Essex

CV-9 CVA-9 CVS-9

USS Essex (CV-9) underway during her first Korean War deployment, circa August 1951-March 1952.

Two F2H-2 Banshees of Fighter Squadron 172 (VF-172) were flying by in the foreground, preparing to land. Nearest plane is Bureau #124954.

The other is probably Bu #124969. Official U.S. Navy photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command. Catalog#: NH 97270.A town and county in Massachusetts.

IV (CV-9; displacement 27,100; length 872'; beam 93'; extreme width 147'6"; draft 28'7"; speed 33 knots; complement 3,448; armament 12 5-inch; class Essex)

The fourth Essex (CV-9) was laid down on 28 April 1941; by Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co., at Newport News, Va.; launched on 31 July 1942; sponsored by Mrs. Artemus L. Gates, wife of the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Air; and commissioned on 31 December 1942, Capt. D.B. Duncan in command. She was reclassified to an attack aircraft carrier (CVA-9) on 1 October 1952, and an antisubmarine warfare support aircraft carrier (CVS-9) on 8 March 1960.

Following her shakedown cruise Essex sailed to the Pacific in May 1943 to begin a succession of victories which would bring her to Tokyo Bay. Departing Pearl Harbor, she participated with TF 15 in carrier operations against Marcus Island (31 August 1943); was designated flagship of TF 14 and struck Wake Island (5-6 October); launched an attack with TG 50.3 against the Gilbert Islands where she also took part in her first amphibious assault, the landing on Tarawa (18-23 November). Refueling at sea, she cruised as flagship of TG 50.3 to attack Kwajalein (4 December). Her second amphibious assault delivered in company with TG 58.2 was against the Marshalls (29 January-2 February 1944).

Essex in TG 58.2 now joined with TG 58.1 and 58.3, to constitute the most formidable carrier striking force to date, in launching an attack against Truk (17-18 February) during which eight Japanese ships were sunk. En route to the Marianas to sever Japanese supply lines, the carrier force was detected and received a prolonged aerial attack which it repelled in a businesslike manner and then continued with the scheduled attack upon Saipan, Tinian and Guam (23 February).

USS Essex (CV-9) scene on the flight deck, looking aft from the carrier's island during her shakedown cruise, 20 March 1943.

Planes parked on deck are F6F-3 fighters (in foreground, with wings folded) and SBD-4 scout bombers.

Official U.S. Navy photograph now in the collections of the National Archives. Catalog#: 80-G-K-698.After this operation Essex proceeded to San Francisco for her single wartime overhaul. She then joined carriers Wasp (CV-18) and San Jacinto (CVL-30) in TG 12.1 to strike Marcus Island (19-20 May) and Wake (23 May). She deployed with TF 58 to support the occupation of the Marianas (12 June-10 August); sortied with TG 38.3 to lead an attack against the Palau Islands (6-8 September), and Mindanao (9-10 September) with enemy shipping as the main target, and remained in the area to support landings on Peleliu. On 2 October she weathered a typhoon and 4 days later departed with TF 38 for the Ryukyus.

For the remainder of 1944 she continued her frontline action, participating in strikes against Okinawa (10 October), and Formosa (12-14 October), covering the Leyte landings, taking part in the battle for Leyte Gulf (24-25 October), and continuing the search for enemy fleet units until 30 October when she returned to Ulithi, Caroline Islands, for replenishment. She resumed the offensive and delivered attacks on Manila and the northern Philippine Islands during November. On 25 November, for the first time in her far-ranging operations and destruction to the enemy, Essex received injury. A kamikaze hit the port edge of her flight deck landing among planes gassed for takeoff, causing extensive damage, killing 15, and wounding 44.

This "cramped her style" very little. Following quick repairs we find her with 3d Fleet off Luzon supporting the occupation of Mindoro (14-16 December). She rode out the typhoon of 18 December and made special search for survivors afterwards. With TG 38.3 she participated in the Lingayen Gulf operations, launched strikes against Formosa, Sakishima, Okinawa, and Luzon. Entering the South China Sea in search of enemy surface forces, the task force pounded shipping and conducted strikes on Formosa, the China coast, Hainan, and Hong Kong. Essex withstood the onslaught of the third typhoon in 4 months (20-21 January 1945) before striking again at Formosa, Miyakp Shima and Okinawa (26-27 January).

During the remainder of the war she operated with TF 58, conducting attacks against the Tokyo area (16-17, and 25 February) both to neutralize the enemy's airpower before the landings on Iwo Jima and to cripple the aircraft manufacturing industry. She sent support missions against Iwo Jima and neighboring islands, but from 23 March to 28 May was employed primarily to support the conquest of Okinawa.

-hit-by-Japanese-Judy-kamikaze-viewed-from-USS-Ticonderoga-(CV-14)-off-Luzon-on-25th-Nov-1944-80-G-270736.jpg)

USS ESSEX (CV-9) Explosion of a Japanese "Judy" kamikaze plane on Essex (CV-9) carrier's flight deck, 25 November 1944.

Essex was operating off Luzon. Note F6F fighter at far left, close to the water. Photographed from Ticonderoga (CV-14).

National Archives photograph. Catalog#: 80-G-270736.In the closing days of the war, Essex took part in the final telling raids against the Japanese home islands (10 July-15 August). Following the surrender, she continued defensive combat air patrols until 3 September when she was ordered to Bremerton, Wash., for inactivation. On 9 January 1947 she was placed out of commission in reserve.

Modernization endowed Essex with a new flight deck, and a streamlined island superstructure, on 15 January 1951 when recommissioned, Captain A. W. Wheelock commanding.

After a brief cruise in Hawaiian waters she began the first of three tours in Far Eastern waters during the Korean war. She served as flagship for Carrier Division 1 and TF 77. She was the first carrier to launch F2H "Banshee" twin-jet fighters on combat missions; on 16 September 1951 one of these planes, damaged in combat, crashed into aircraft parked on the forward flight deck causing an explosion and fire which killed seven. After repairs at Yokosuka she returned to front-line action on 3 October to launch strikes up to the Yalu River and provide close air support for U.N. troops.

On 1 December 1953 she started her final tour of the war, sailing the China Sea with the Peace Patrol. From November 1954 to June 1955 she engaged in training exercises, operated for 3 months with the 7th Fleet, assisted in the Tachen Islands evacuation, and engaged in air operations and fleet maneuvers off Okinawa.

In July 1955 Essex entered Puget Sound Naval Shipyard for repairs and extensive alterations, including installation of an angled flight deck. Modernization completed, she rejoined the Pacific Fleet in March 1956. For the next 14 months the carrier operated off the west coast, except for a 6-month cruise with the 7th Fleet in the Far East. Ordered to join the Atlantic Fleet for the first time in her long career, she sailed from San Diego on 21 June 1957, rounded Cape Horn, and arrived in Mayport, Fla., on 1 August.

In the fall of 1957 Essex participated as an antisubmarine carrier in the NATO exercises, "Strike Back," and in February 1958 deployed with the 6th Fleet until May when she shifted to the eastern Mediterranean. Alerted to the Middle East crisis on 14 July 1958 she sped to support the U.S. Peace Force landing in Beirut, Lebanon, launching reconnaissance and patrol missions until 20 August. Once again she was ordered to proceed to Asian waters, and transitted the Suez Canal to arrive in the Taiwan operational area where she joined TF 77 in conducting flight operations before rounding the Horn and proceeding back to Mayport.

Essex joined with the 2d Fleet and British ships in Atlantic exercises and with NATO forces in the eastern Mediterranean during the fall of 1959. In December she aided victims of a disastrous flood at Frejus, France.

In the spring of 1960 she was converted into an ASW Support Carrier and was thereafter homeported at Quonset Point, R.I. Since that time she has operated as flagship of Carrier Division 18 and Antisubmarine Carrier Group Three. She conducted rescue and salvage operations off the New Jersey coast for a downed blimp; cruised with midshipmen, and was deployed on NATO and CENTO exercises. In November she joined the French navy in Operation "Jet Stream" and since that time has continued her widespread activities in protection of freedom and peace.

Essex received the Presidential Unit Citation, and 13 battle stars for World War II service; 4 battle stars and the Navy Unit Commendation for Korean war service.

Published: Thu Nov 07 16:21:09 EST 2019

- Flight Simulators

IL-2 Sturmovik 'Cliff's of Dover' Blitz - has no 3D model

IL-2 Sturmovik Battle of Stalingrad - has no 3D model

DCS World - has no 3D model

USN Top Fighter Pilot by Squadron and Leading Commanding Officer including Unit Total Kills Squadron # Nickname Start End A/C Carrier/Base Top Ace (kills w/ sqn) CO (kills w/ sqn) Kills # Aces VF-1 High Hatters Nov-43 Aug-44 F6F Yorktown CV-10 Richard Eastmond (9) B.M. Strean 100 3 VF-2 Rippers Mar-44 Sep-44 F6F Hornet CV-12 Cdr. William A. Dean (10) 240 28 VF-3 Felix the Cat Dec-41 May-42 F4F Lexington CV-2 Butch O'Hare (5) Jimmy Thach 18 1 May-42 Jun-42 F4F Yorktown CV-5 Elbert McCuskey (5) Jimmy Thach 34.5 1 VF-5 Aug-42 Oct-42 F4F Saratoga CV-3 H. M. Jensen (7) Leroy Simpler 78 4 Oct-43 Apr-44 F6F Yorktown CV-10 Robert Duncan (7) Ed Owens (5) 93.5 7 VF-6 Shooting Stars Dec-41 Oct-42 F4F Enterprise CV-6 Donald E. Runyon (8) James S. Gray 63 1 VF-6 Aug-43 Feb-44 F6F various CV's Alexander Vraciu (9) H.W. Harrison 37.5 0 VF-7 Sep-44 Jan-45 F6F Hancock CV-19 Lt. Cdr. L. J. Check (10) 72 2 VF-8 Dec-41 Jun-42 F4F Hornet CV-8 Merrill Cook (2) Sam Mitchell 5 0 Mar-44 Oct-44 F6F Bunker Hill CV-17 Cdr. William Collins (9) 156 13 VF-9 Cat o' Nines Oct-43 Mar-44 F6F Essex CV-9 Hamilton McWhorter (10) Phil Torrey 116 10 est. Mar-45 Jun-45 F6F Yorktown CV-10 Eugene Valencia (23) John S. Kitten 129 10 est. VF-10 Grim Reapers Oct-42 May-43 F4F Enterprise CV-6 Swede Vejtasa (7.25) J.H. Flatley 43 1 Jan-44 Jun-44 F6F Enterprise CV-6 Richard Devine (8) William Kane 88 5 Feb-45 Apr-45 F4U Intrepid CV-11 P. L. Kirkwood (8) Walter E. Clarke 87 7 VF-11 Sundowners May-43 Jul-43 F4F Guadalcanal Charles Stimpson (6) Charles White 52 2 Oct-44 Jan-45 F6F Hornet CV-12 Charles Stimpson (10) E. G. Fairfax 106 5 VF-12 Sep-43 Jun-44 F6F Saratoga CV-3 John Magda (4) R.G. Dose 20 0 Jan-45 Jun-45 F6F Randolph CV-15 Lt. Cdr. Frederick H. Michaelis (5) 51 2 VF-13 Black Cats Jul-44 Nov-44 F6F Franklin CV-13 Albert Pope (7) Wilson Coleman (6) 86 3 VF-14 Iron Angels May-44 Nov-44 F6F Wasp CV-18 William Knight (7.5) R. Gray 146 8 VF-15 Fighting Aces May-44 Nov-44 F6F Essex CV-9 McCampbell, Duncan, Rushing, Strane, Twelves James Rigg (11) 310 26 VF-16 Fighting Airedales Oct-43 Jun-44 F6F Lexington CV-16 Alexander Vraciu (10) Paul D. Buie (9) 136.5 7 VF-17 Jolly Rogers Oct-43 Mar-44 F4U Solomons Ike Kepford (16) Tom Blackburn (11) 152 11 VF-18 Oct-43 Mar-44 F6F Bunker Hill CV-17 Lt. Cdr. Sam Silber (6) 74 1 Aug-44 Nov-44 F6F Intrepid CV-11 Cecil Harris (22) Ed Murphy 176.5 13 VF-19 Satan's Kittens Jul-44 Nov-44 F6F Lexington CV-16 William Masoner Jr. (10) T. Hugh Winters (8) 155 11 VF-20 Aug-44 Jan-45 F6F Enterprise CV-6/etc. Douglas Baker (16.33) Fred Bakutis (7.5) 158 9 VF-21 Feb-43 Jul-43 F4F Guadalcanal Ross Torkelson (6) John Hulme 69 3 Jul-44 Oct-44 F6F Belleau Wood CVL-24 Bob Thomas (5) V. F. Casey 40 1 VF-22 Sep-44 Jan-45 F6F Cowpens CVL-25 Clement Craig (12) Thomas Jenkins 49.5 3 VF-23 Aug-43 May-44 F6F Princeton CVL-23 L.H. Kerr (4.83) H.L. Miller 35 0 VF-26 Apr-44 Oct-44 FM2 Santee CVE-29 Kenneth Hippe (6) Harold Funk 31 1 VC-27 Oct-44 Jan-45 FM2 Savo Island Ralph Elliott (9) P. W. Jackson 61 1 VF-27 May-44 Oct-44 F6F Princeton CVL-23 James Shirley (12) Fred Bardshar (7.5) 134 10 VF-28 May-44 Dec-44 F6F Monterey CVL-26 Oscar Bailey (5) Roger Mehle 55 2 VF-29 Oct-44 Apr-45 F6F Cabot CVL-28 Robert Murray (10.3) William Eder (6.5) 113 12 VF-30 Jan-45 Jun-45 F6F Belleau Wood CVL-24 James Reber (11) Douglas A. Clark 110 7 VF-31 Meat Axers Jan-44 Sep-44 F6F Cabot CVL-28 Cornelius Nooy (19) Bob Winston 165.5 14 VF-32 Outlaw's Bandits Mar-44 Oct-44 F6F Langley CVL-27 Lt. Cdr. Eddie Outlaw (6) 44 2 VF-33 Aug-43 Jan-44 F6F Solomons Frank Schneider (7) Hawley Russell 74.5 3 VF(N)-41 Aug-44 Jan-45 F6F Independence CVL-23 William Henry (9.5) T. F. Caldwell 46 2 VF-42 Dec-41 May-42 F4F Yorktown CV-5 Art Brassfield (4.83) Oscar Pedersen 25 0 VF-44 Crusaders Oct-44 Feb-45 F6F Langley CVL-27 Cdr. Malcolm T. Wordell (7) 47 3 VF-45 Nov-44 May-45 F6F San Jacinto CVL-30 James B. Cain (8) Gordon Schechter 81.5 6 VF-47 Fighting Cocks Mar-45 Aug-45 F6F Bataan CVL-29 Samuel Hibbard (7.33) Albert Clancy 67.5 1 VF-50 Devil Cats Apr-44 Jul-44 F6F Bataan CVL-29 Daniel Rehm (6) J.C. Strange 61 4 VF-51 Apr-44 Nov-44 F6F San Jacinto CVL-30 William Maxwell (7) C. L. Moore 50.5 1 VF-60 Nov-43 Oct-44 F6F Suwanee CVE-27 R. Singleton (3.25) H.O. Feilbach 25 0 VF-72 Jul-42 Oct-42 F4F Hornet CV-8 George Wrenn (5.25) Henry Sanchez 38 1 VF-80 Vorse's Vipers Nov-44 Jan-45 F6F Ticonderoga CV-14 Patrick Fleming (19) Leroy Keith 159.5 10 VF-82 Jan-45 Jun-45 F6F Bennington CV-20 Robert Jennings (7) Edward Hassell 85 5 VF-83 Kangaroos Mar-45 Sep-45 F6F Essex CV-9 Thaddeus Coleman (8) H.A. Sampson 137 11 VBF-83 Mar-45 Sep-45 F4U Essex CV-9 Thomas Reidy (10) Frank Patriarca 91 3 VF-84 Wolf Gang Jan-45 Jun-45 F4U Bunker Hill CV-17 Doris Freeman (7) Roger R. Hedrick 137 4

Naval Base Kitsap Bremerton, Washington Map

USS Essex (CV-9) notes:

USS Essex (CV-9) citations:

- 'USS Essex (CV-9)'. U.S. Navy. 11 June 2009. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017.

- Essex (CV-9) iv.

- Smith, Peter C. (2014). Kamikaze: To Die for the Emperor. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books Ltd. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-78159-313-4.

- 'Big Warships Return From Pacific Sector'. The San Bernardino Daily Sun. Vol. 52. San Bernardino, California. Associated Press. 16 September 1945. p. 5.

- History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the first Indochina War, 1947-1954 (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 2004. pp. 162–167. ISBN 0-16-072430-9.

- 'U.S. denies Arabian Sea 'buzzing''. The Times. No. 54925. London. 10 November 1960. col C, p. 12.

- Wyden 1979, pp. 125–127, 130, 214, 240–241.

- Kennedy 1969.

- Nautilus (SSN-571) iv.

- That time a Soviet bomber crashed into the sea after buzzing a US aircraft carrier 14 April 2016

- Leone, Dario (5 November 2019). 'That Time a Soviet Tu-16 Crashed Into Sea After Buzzing USS Essex Aircraft Carrier'. The Aviation Geek Club.

- 'Apollo 7 returns safely to Earth in 1968, raising hopes that man would soon land on the moon'. New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016.

- Hansen 2005.

- 'Essex CVS-9'. NavSource Naval History. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015.

- St. John, Philip A. (1999). USS Essex CV/CVA/CVS-9. Turner Publishing Company. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-56311-492-2.

- 'Essex CVS-9'. Naval Vessel Registry.

Bibliography:

- Streb, Richard W. (1999). Life and Death Aboard the USS Essex. Pittsburgh: Dorrance Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8059-4605-5.

- 'Essex (CV-9) iv'. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. 15 January 2015.

- Hansen, James R. (2005). First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-5751-0.

- Kennedy, Robert F. (1969). Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-333-10312-8.

- 'Nautilus (SSN-571) iv'. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. 27 May 2014.

- Wyden, Peter (1979). Bay of Pigs: The Untold Story. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-24006-6.

Magazine References: +

- Airfix Magazines (English) - http://www.airfix.com/

- Avions (French) - http://www.aerostories.org/~aerobiblio/rubrique10.html

- FlyPast (English) - http://www.flypast.com/

- Flugzeug Publikations GmbH (German) - http://vdmedien.com/flugzeug-publikations-gmbh-hersteller_verlag-vdm-heinz-nickel-33.html

- Flugzeug Classic (German) - http://www.flugzeugclassic.de/

- Klassiker (German) - http://shop.flugrevue.de/abo/klassiker-der-luftfahrt

- Le Fana de L'Aviation (French) - http://boutique.editions-lariviere.fr/site/abonnement-le-fana-de-l-aviation-626-4-6.html

- Le Fana de L'Aviation (French) - http://www.pdfmagazines.org/tags/Le+Fana+De+L+Aviation/

- Osprey (English) - http://www.ospreypublishing.com/

- Revi Magazines (Czech) - http://www.revi.cz/

Web References: +

- Wikipedia - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lexington-class_aircraft_carrier

- Naval History and Heritage Command https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/e/essex-iv.html

- Wikipedia - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isoroku_Yamamoto

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

Editor for Asisbiz: Matthew Laird Acred

If you love our website please donate so we can make this site even better !!

-80-G-373838.jpg)

-9th-Aug-1944-80-G-0373839.jpg)

-on-the-bridge-Feb-1944-80-G-K-13982.jpg)

-examine-the-damaged-propeller-over-Marcus-Island-Raid-19-20th-May-1944-01.jpg)

-damaged-over-Marcus-Island-19th-May-1944-80-G-373614.jpg)

-Torpcats-burst-into-flames-after-landing-aboard-USS-Essex-(CVA-9)-Korean-War-16th-Oct-1951-01.jpg)

-aboard-USS-Essex-(CV-9)-adding-another-a-victory-flag-to-the-scoreboard-Feb-1944.jpg)

-poses-for-a-squadron-picture-on-board-USS-Essex-(CV-9)-Feb-1944-80-G-217590.jpg)

-poses-for-a-squadron-picture-on-board-USS-Essex-(CV-9)-Feb-1944-80-G-217606.jpg)

-in-17th-Feb-1944-80-G-217587.jpg)

-Feb-1944-80-G-217565.jpg)

-in-Feb-1944-80-G-217624-A.jpg)

-in-Feb-1944-80-G-217622.jpg)

-in-March-1944-80-G-217594.jpg)

-at-anchor-off-Saipan-30th-July-1944-80-G-373647.jpg)

-task-group-38.3-leaving-after-strikes-on-the-Saigon-area-12th-Jan-1945-80-G-300666.jpg)

-task-group-38.3-leaving-after-strikes-on-the-Saigon-area-12th-Jan-1945-80-G-300673.jpg)

-task-group-38.3-leaving-after-strikes-on-the-Saigon-area-12th-Jan-1945-80-G-300673C.jpg)

-20th-May-1945-80-G-373595.jpg)

-on-a-raid-over-Japan-with-Mt-Fujiyama-10th-Jul-1945-80-G-490231.jpg)

-prepares-for-a-water-landing-near-a-destroyer-Okinawa-invasion-1st-April-1945-01.jpg)

-flying-in-formation-12th-Jan-1945-80-G-37312.jpg)

-hit-by-AA-over-Okinawa-28th-March-1945-80-G-373751.jpg)

-24th-July-1945-80-G-490152.jpg)

-24th-July-1945-80-G-490159.jpg)

-on-24th-July-1945-80-G-490162.jpg)

-planes-Battle-off-Cape-Engano-25th-Oct-1944-80-G-47162.jpg)

-14th-Oct-1944-80-G-373663.jpg)

-after-being-shot-down-11th-Nov-1943-80-G-206615.jpg)

-off-Japan-on-19th-Mar-1945-80-G-310112.jpg)

-during-air-attacks-on-TF-58-off-the-Marianas-22nd-Feb-1944-80-G-221848.jpg)

-01.jpg)

-02.jpg)

-off-Okinawa-14th-May-1945-80-G-324120.jpg)

-off-Okinawa-14th-May-1945-80-G-324121.jpg)

-80-G-490110.jpg)

-80-G-490113.jpg)

-part-of-Task-Force-77-on-21st-Feb-1952-NH-97109.jpg)

-underway-in-the-Pacific-with-Task-Force-58.2-circa-1943-44-80-G-300907.jpg)

-USS-Indiana-(BB-58)-and-USS-Massachusetts-(BB-59)-80-G-156819.jpg)

-at-Mare-Island-Navy-Yard-12th-Jan-1942-19-N-26641.jpg)

-at-Mare-Island-Navy-Yard-30th-March-1942-19-N-29702.jpg)

-at-Mare-Island-Navy-Yard-30th-March-194219-N-29705.jpg)

-rescued-by-a-OS2U-3-Kingfisher-is-George-M-Blair-(left)-from-Truk-Lagoon-18th-Feb-1944-80-G-216624.jpg)

-at-sea-2nd-May-1944-80-G-376087.jpg)

-off-San-Diego-California-during-a-demonstration-for-Movietone-News-14th-Sep-1936-80-G-423380.jpg)

-photographed-28th-April-1938-80-G-425599.jpg)

-10th-May-1943-80-G-680997.jpg)

-afloat-in-the-James-River-immediately-after-her-launching-31st-July-1942-NH-54107.jpg)

-afloat-in-the-James-River-immediately-after-her-launching-31st-July-1942-NH-54109.jpg)

-afloat-in-the-James-River-immediately-after-her-launching-31st-July-1942-NH-54110.jpg)

-afloat-in-the-James-River-immediately-after-her-launching-31st-July-1942-NH-67736.jpg)

-after-a-Hellcat-drop-tank-burst-flames-engulfing-the-flight-deck-16th-Dec-1944-01.jpg)

-after-a-Hellcat-drop-tank-burst-flames-engulfing-the-flight-deck-16th-Dec-1944-02.jpg)

-after-a-Hellcat-drop-tank-burst-flames-engulfing-the-flight-deck-16th-Dec-1944-03.jpg)

-after-her-San-Francisco-refit-15th-April-1944-01.jpg)

-after-her-San-Francisco-refit-15th-April-1944-02.jpg)

-after-her-San-Francisco-refit-15th-April-1944-03.jpg)

-after-her-San-Francisco-refit-15th-April-1944-04.jpg)

-aircraft-attacked-Dumaguete-airfield-to-support-the-landings-on-Peleliu-12th-Sep-1944-01.jpg)

-aircraft-attacked-shipping-and-oil-storage-at-Surigao-Mindanao-9th-Sep-1944-01.jpg)

-aircraft-attacked-shipping-at-Manila-Bay-5th-Nov-1944-02.jpg)

-and-a-destroyer-refueling-in-a-storm-from-USS-Pamansett-(AO-85)-East-China-Sea-17th-Jan-1945.jpg)

-and-T2-SE-A1-oiler-USS-Tallulah-AO-50-refueling-in-heavy-seas-off-Luzon-9th-Nov-1944-01.jpg)

-and-T2-SE-A1-oiler-USS-Tallulah-AO-50-refueling-in-heavy-seas-off-Luzon-9th-Nov-1944-02.jpg)

-at-anchor-at-Majuro-Atoll-2nd-Mar-1944-80-G-300874.jpg)

-at-sea-during-the-Okinawa-Campaign-20th-May-1945-02.jpg)

-at-sea-with-an-overload-of-aircraft-on-her-flight-deck-14th-May-1944-80-G-373580.jpg)

-based-TBMs-and-SB2Cs-dropping-bombs-on-Hokadate-Japan-15th-July-1945-80-G-490232.jpg)

-based-TBMs-and-SB2Cs-dropping-bombs-on-Hokadate-Japan-15th-July-1945-NARA-80-G-490232.jpg)

-being-hit-by-a-Japanese-Judy-during-Kamikaze-attacks-off-Luzon-25th-Nov-1944-80-G-270738.jpg)

-being-hit-by-a-Japanese-Judy-during-Kamikaze-attacks-off-Luzon-25th-Nov-1944-80-G-270740.jpg)

-being-hit-by-a-Japanese-Judy-during-Kamikaze-attacks-off-Luzon-25th-Nov-1944-80-G-273032.jpg)

-being-hit-by-a-Japanese-Judy-during-Kamikaze-attacks-off-Luzon-25th-Nov-1944-UA47812.jpg)

-docked-at-Pearl-Harbor-Navy-Yard-8th-Aug-1943-80-G-K-547.jpg)

-docked-at-Pearl-Harbor-Navy-Yard-8th-Aug-1943-80-G-K-551.jpg)

-during-the-Japanese-air-attack-during-battle-of-Leyte-Gulf-Oct-1944-80-G-284724.jpg)

-en-route-to-raid-Marcus-Island-30th-Aug-1943-80-G-K-581.jpg)

-F6F-Hellcat-VF-15-damaged-over-Wake-pilot-Lt-JJ-Collins-on-a-stretcher-after-crash-landing-23rd-May-1944.jpg)

-F6F-Hellcat-VF-15-damaged-over-Wake-pilot-Lt-JJ-Collins-on-a-stretcher-after-crash-landing-23rd-May-1944-80-G-373619.jpg)

-F6F-Hellcat-VF-15-White-23-damaged-over-Wake-Lt-JJ-Collins-belly-landing-23rd-May-1944.jpg)

-F6F-Hellcat-VF-15-White-23-damaged-over-Wake-Lt-JJ-Collins-belly-landing-23rd-May-1944-80-G-373617.jpg)

-fire-erupts-from-an-F4U-Corsair-after-it-crashed-into-the-barrier-8th-April-1945-80-G-373760.jpg)

-fire-erupts-from-an-F4U-Corsair-after-it-crashed-into-the-barrier-8th-April-1945-80-G-373761.jpg)

-fire-on-the-flight-deck-after-a-McDonnell-F2H-2-Banshee-crashed-during-ops-off-Korea-16th-Sep-1951-80-G-433492.jpg)

-fire-on-the-flight-deck-after-a-McDonnell-F2H-2-Banshee-crashed-during-ops-off-Korea-16th-Sep-1951-80-G-433493.jpg)

-fire-on-the-flight-deck-after-a-McDonnell-F2H-2-Banshee-crashed-during-ops-off-Korea-16th-Sep-1951-80-G-433494.jpg)

-fire-on-the-flight-deck-after-a-McDonnell-F2H-2-Banshee-crashed-during-ops-off-Korea-16th-Sep-1951-80-G-433497.jpg)

-fire-on-the-flight-deck-after-a-McDonnell-F2H-2-Banshee-crashed-during-ops-off-Korea-16th-Sep-1951-80-G-433507.jpg)

-flight-deck-during-her-shakedown-cruise-20th-Mar-1943-80-G-K-698.jpg)

-flight-deck-wait-for-snowy-weather-to-break-of-Korea-18th-Jan-1952-80-G-437709.jpg)

-flight-deck-wait-for-snowy-weather-to-break-of-Korea-18th-Jan-1952-80-G-437710.jpg)

-flight-deck-wait-for-snowy-weather-to-break-of-Korea-18th-Jan-1952-80-G-437711.jpg)

-flight-deck-with-F6F-3-Hellcats-and-SBD-4-Dauntlesses-20th-Mar-1943-80-GK-698.jpg)

-in-heavy-seas-during-her-deployment-12th-Jan-1960-NH-98517.jpg)

-in-port-with-Corsairs-on-deck-UA-53601.jpg)

-intended-camouflage-measure-31-32-33-design-10A-drawing-19th-July-1943-80-G-159382.jpg)

-intended-camouflage-measure-31-32-33-design-10A-drawing-19th-July-1943-80-G-170026.jpg)

-intended-camouflage-measure-33-design-10A-drawing-19th-Jan-1944-80-G-170025.jpg)

-in-the-Guld-of-Paria-Trinidad-20th-March-1943-80-GK-429.jpg)

-launching-with-Mrs-Artemus-Gates-is-about-to-christen-at-the-Newport-New-31st-July-1942-NH-54100.jpg)

-launching-with-Mrs-Artemus-Gates-is-about-to-christen-at-the-Newport-New-31st-July-1942-NH-54101.jpg)

-launching-with-Mrs-Artemus-Gates-is-about-to-christen-at-the-Newport-New-31st-July-1942-NH-54102.jpg)

-launching-with-Mrs-Artemus-Gates-is-about-to-christen-at-the-Newport-New-31st-July-1942-NH-54103.jpg)

-launching-with-Mrs-Artemus-Gates-is-about-to-christen-at-the-Newport-New-31st-July-1942-NH-54104.jpg)

-many-hands-make-light-work-as-crew-members-clean-the-flight-deck-01.jpg)

-Ordnance-men-with-bombs-on-the-flight-deck-Marcus-Island-19th-May-1944-80-G-373593.jpg)

-planes-attack-Shimane-Maru-at-Kure-Naval-Base-Japan-19th-March-1945-NH-95782.jpg)

-planes-attack-Shimane-Maru-at-Kure-Naval-Base-Japan-19th-March-1945-NH-95783.jpg)

-planes-attack-two-Japanese-aircraft-carrier-Ikoma-at-Kure-Naval-Base-Japan-19th-March-1945-NH-95779.jpg)

-planes-attack-two-Japanese-aircraft-carrier-Ikoma-at-Kure-Naval-Base-Japan-19th-March-1945-NH-95780.jpg)

-planes-attack-two-Japanese-aircraft-carriers-at-Kure-Naval-Base-Japan-19th-March-1945-NH-95778.jpg)

-planes-attack-two-Japanese-aircraft-carriers-at-Kure-Naval-Base-Japan-19th-March-1945-NH-95781.jpg)

-receives-provisions-from-USS-Mercury-(AK-42)-operating-off-Okinawa-27th-April-1945-80-G-373776.jpg)

-recon-photograph-taken-over-Wake-during-a-mission-sortie-7th-Oct-1943-01.jpg)

-returning-to-the-US-from-her-first-Korean-War-deployment-at-San-Diego-California-25th-Mar-1952-NH-97111.jpg)

-right-after-commissioning-31st-Dec-1942-01.jpg)

-schematic-diagram-2d-technical-drawing-or-blueprint-by-JR-Barrett-0A.jpg)

-silhouetted-against-the-sun-while-operating-in-the-South-Pacific-late-1943-80-G-K-15556.jpg)

-underway-at-1615hrs-during-May-1943-80-G-68097.jpg)

-underway-off-the-Gilbert-Islands-as-viewed-from-another-carrier-29th-Nov-1943-01.jpg)

-VB-15-and-VT-15-Marianas-campaign-USS-San-Jacinto-CVL-30-USS-Wasp-CV-18-27th-May-1944-80-G-373623.jpg)

-with-2-F2H-2-Banshees-(VF-172)-during-her-first-Korean-War-deployment-circa-Aug-1951-Mar-1952-NH-97270.jpg)

-with-deckload-of-F4U-1D-Corsairs-F6F-Hellcats-and-TBM-Avengers-in-Philippines-25th-Jan-1945-80-G-373724.jpg)

-with-other-deactivated-warships-tied-up-at-Pier-91-Seattle-Washington-in-April-1946-80-G-373247.jpg)

-with-USS-Iowa-(BB-61)-at-anchor-at-Majuro-Atoll-2nd-Apr-1944-80-G-300903.jpg)

-as-modernized-photograph-taken-of-the-starboard-bow-9th-May-1956-NH-67700.jpg)

-as-modernized-underway-in-the-South-China-Sea-26th-Aug-1956-NH-67721.jpg)

-as-modernized-underway-in-the-South-China-Sea-26th-Aug-1956-NH-67737.jpg)

-assigned-Carrier-Air-Group-11-(CVG-11)-and-deployed-to-the-Western-Pacific-16th-July-1956-to-26th-Jan-1957.jpg)

-on-deck-are-aircraft-of-Carrier-Anti-Submarine-Air-Group-60-(CVSG-60)-in-1962.jpg)

-welcomes-The-Apollo-7-astronauts-WM-Schirra-DF-Eisele-and-W-Cunningham-aboard-in-22nd-Oct-1968.jpg)

-at-the-Mare-Island-Navy-Yard-California-29th-May-1942-19-N-30484.jpg)

-off-the-Mare-Island-Navy-Yard-California-20th-April-1942-19-N-29840.jpg)

-preparing-to-refuel-at-sea-8th-Jan-1943-80-G-38034.jpg)

-at-anchor-at-Majuro-Atoll-2nd-Apr-1944-80-G-300909.jpg)

-coming-into-Ulithi-Anchorage-during-a-break-in-operations-on-24th-Nov-1944-NH-58573.jpg)

-underway-at-15-knots-off-Point-Wilson-Washington-on-11th-July-1944-NH-97255.jpg)

-at-Mare-Island-Navy-Yard-17th-Feb-1942-19-N-28346.jpg)

-at-sea-May-1944-80-G-376093.jpg)

-underway-at-sea-28th-April-1938-80-G-425603.jpg)

-at-sea-during-the-Philippines-campaign-12th-Dec-1944-80-G-301357.jpg)

-steaming-in-Iron-Bottom-Sound-off-Guadalcanal-viewed-by-USS-Montpelier-(CL-57)-23rd-Mar-1944-80-G-48564.jpg)

-01.jpg)

-during-the-Okinawa-Campaign-1945.jpg)

-1945-01.jpg)

-during-operations-off-Korea-Jan-1952-80-G-443663.jpg)

-after-rescueing-downed-crew-from-Truk-Lagoon-18th-Feb-1944-01.jpg)

-Typhoon-Cobra-hit-the-Third-Fleet-on-18th-Dec-1944-01.jpg)

-rolling-sharply-as-she-rides-out-Typhoon-Cobra-from-USS-Essex-(CV-9)-13th-Jan-1945-80-G-305484.jpg)

-rolling-sharply-as-she-rides-out-Typhoon-Cobra-from-USS-Essex-(CV-9)-13th-Jan-1945-NH-89374.jpg)

-as-she-rides-out-Typhoon-Cobra-seen-from-USS-Brush-(DD-745)-13th-Jan-1945-NH-89376.jpg)

-with-2-F2H-2-Banshees-(VF-172)-during-her-first-Korean-War-deployment-circa-Aug-1951-Mar-1952-NH-97270.jpg)

-flight-deck-with-F6F-3-Hellcats-and-SBD-4-Dauntlesses-20th-Mar-1943-80-GK-698.jpg)